Ecuador

ECUADOR (officially La Repicblica del Ecuador), a republic of South America, bounded on the north and north-east by Colombia and Peru, on the east-south-east and south by Peru, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean. The northern boundary (about 68o m.) begins on the Pacific coast at the mouth of the Rio Mataje, I° 3o' N. and ascends this stream to about I° 18' N. where it crosses the ridge into the Rio Mira. The boundary ascends this stream to the confluence with the Rio San Juan, ascends the latter to its source, crosses the summit of the Andes in about o° 45' N. and then descends the east slope of the Andes via the Rio Carchi, crossing to the Rio Aguarico and descending this to o° 23' N. where it crosses to the Rio San Miguel and descends this stream to the confluence with the Rio Putumayo in long. 75° 5 2' W. of Greenwich. It then turns south-west over land to the top of the divide between the Rio Putumayo and Rio Aguarico, about o° 4' S. and 76° 15' W. a surveyed distance of about 310 m. from the Pacific. From this point the boundary follows the divide between the Rio Putumayo and Rio Napo to the source of the Rio Ambiyacu which river it follows to the Amazon at 3° 19' S. and 71° 5o' W. The boundary along the divide between the Putumayo and the Napo is not surveyed, but the approximate distance from the Pacific to the Amazon is about 68o miles.

In 1927 Colombia ceded to Peru, a narrow strip of territory, about 430 m. E. and W., just N. of the Ecuador boundary as established by Colombia and Ecuador in 1916. The southern boundary follows the centre of the main channel of the Amazon from the mouth of the Rio Ambiyacu, to that of the Rio Huanca bamba 78° 38' W. (about 52o m.). It then ascends the Rio Huancabamba to its source and crosses the Andes at 4° 4o' S. to descend the Macara to the Catamayo. It then descends this river to the confluence with the Alamor which it ascends to the Que brada de los Pavas. Ascending this the line then crosses a divide into the Rio Tumbez which it follows to the Pacific. This bound ary is apparently undisputed by Peru from the Pacific at the mouth of the Rio Tumbez to the headwaters of the Rio Huanca bamba.

The area of Ecuador (not including the Galapagos islands, q.v.), is 167,600 sq.m.; but a large portion is claimed by Peru (q.v.). Attempts to settle the boundary dispute between Ecuador and Peru, which has existed since the independence of Ecuador in 1831, have failed. Under an agreement dated Dec. 15, 1894, the dispute was referred to the Spanish sovereign as arbiter but no settlement was arrived at. Peru has, among other rivers, the Napo river as far as the mouth of the Aguarico, the Pastaza as far as the Huasaga and a large part of the Morona.

Andean Region.

Ecuador is largely mountainous. It is traversed from north to south (about 500 m.), by the Andes Mountains (maximum elevation in Chimborazo 20,576 feet). The lowest divide in the cordillera, 6,888 ft., is on the Peruvian boundary.The Andes are narrowest in Ecuador, which is divided into three regions : the Andean highlands, the coastal region between the Andes and the Pacific and the Amazon region or Oriente on the east of the high Andes. The Andean region ends on the west in elevations of about 1,50o ft. above the sea. In the south, around the gulf of Guayaquil there is only a narrow belt of low coastal region. From a point a few miles east of Guayaquil, however, to just south of the Equator, the Andes terminate along the east side of the Guayas basin. A line from the head of the Guayas basin at Sto. Domingo de los Colorados on the Rio Toachi north to a few miles east of San Lorenzo terminates the western bound ary of the Andean region in Ecuador. On the east however, the base of the Andes may be taken at points such as Macas (3,580 ft.) and Mera (3,8o8 ft.). In general the 4,000 ft. unbroken contour from the Colombian to the Peruvian border bounds the Andean region on the east.

The width of this mass from base to base varies from a mini mum of 73 m. (Bucay to Macas), to a maximum of 183 m. (Zapo tello and Santiago). The average width is about 10o m. (Sto. Domingo de los Colorados-Tena, 1,680 ft.). The longitudinal profile of the Andean summits from north to south, coinciding with the watershed between the Atlantic and Pacific varies from 20,576 ft. in Chimborazo to about 6,90o ft. in the south near the Peruvian boundary.

That portion of the Andes from about 2° S. to the Colombian frontier is characterized by lofty, volcanic peaks, many covered with perpetual snow and ice, some active. Beginning with Cumbal (15,711 ft.) and Chilles (15,678 ft.) just north of the Colombian boundary, the most important are Yanaurcu (14,881), Cotocachi (16,328), Imbabura (15,028), Mojanda (14,038), Cayambe (19,186), Saraurcu (15,502) , Pichincha (15,918), Antisana (18,715), Cotopaxi (19,613), Corazon (15,871), Iliniza (17,405), Quilindana (16,174), Carihuairazo (16,515), Chimborazo (20, Tunguragua (16,690), Altar (17,73o) and Sangay (17,464). These are irregularly distributed on a basal plateau and viewed from a great distance each volcanic unit is only a small mass having a prominence of but 3,000 or 4,000 ft. above the general level of the upland. Antisana, for example, can be described as a mass about 4 m. in diameter at its base and rising from an ele vation of 15,00o ft. to 18,715 ft. above the sea.

In the volcanic part of the Ecuador Andes the streams flow in old valleys often several miles wide filled with hundreds of feet of ash and lava. The streams are therefore rejuvenated and flow in narrow canyons with steep walls.

The streams of the Andean highland region are all torrential and flow both to the Atlantic and Pacific. The largest drainage basin on the Andes is the Pastaza system, which is composed of the south-flowing Patate and the north-flowing Chambo. The longitudinal valley in which these flow is about i oo m. long. The two streams unite at the middle of this section near Banos (6,000 ft.) to form the Pastaza and eventually reach the Amazon. To the north of the Patate-Chambo basin, about 4o m. of the upper part of the Guallabamba is in a valley which has the same north-south trend as its neighbour to the south. These two units, totalling a length of 14o m. in the most populous part of Ecuador and separated by an east-west divide of an elevation of only i1,65o ft. form a strikingly narrow, longitudinal depression and it has been customary to refer to the higher portions of the Andes to the east and west of this as the eastern and western cordillera. But the Andes are so narrow in Ecuador that it seems best to recognize them as one mountain mass. The Mira in the north flows to the Pacific and has a considerable portion of its drainage on the Andean highlands. This is often referred to as the Ibarra basin, another clearly defined mountain park. The Andes of southern Ecuador are pretty well and irregularly cut up by both Pacific and Atlantic tributaries whose headwaters are interlocked. Among the main streams of the former class are the Paute, the Zamora and the Chinchipe. To the latter belong the Naranjal, the Jubones, the Tumbez and the Catamayo. There are no large lakes in Ecuador.

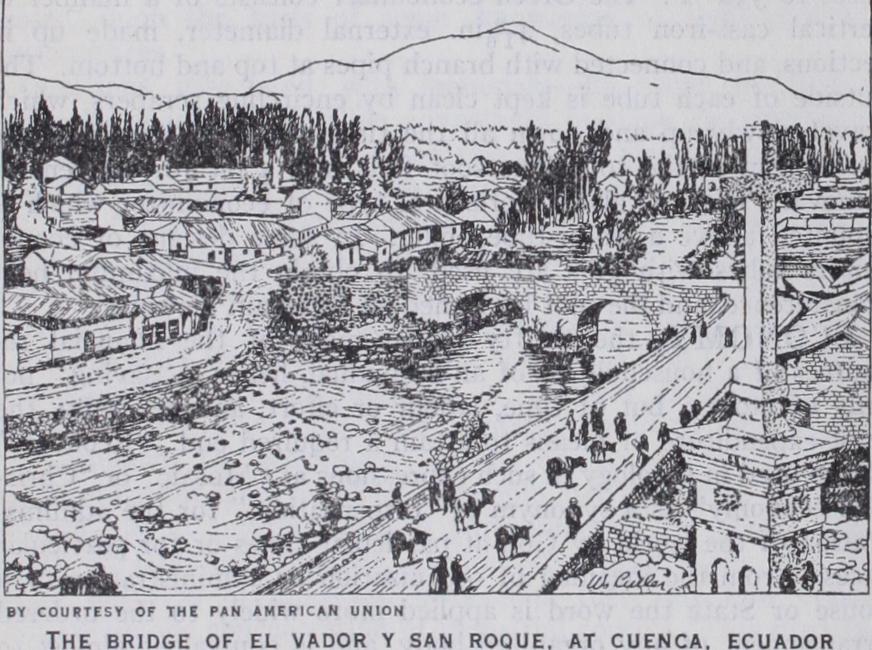

All of the Andean highlands with the exception of the eastern and western slopes are treeless and highly suitable for agricul ture. The forests of the east and west slopes are nearly unin habited. The central part of the Andes which is also the most elevated and has the best climate has such cities as Ibarra (q.v.), Quito (q.v.), Latacunga (q.v.), Ambato (q.v.), Riobamba (q.v.), Cuenca (q.v.) and Loja.

Pacific Coastal Region.—The coastal region forms an area in places i i 5 m. wide extending from the Andes to the Pacific and from the Peruvian boundary in lat. 3° 30' S. to Colombia, i ° 30' N. This is mostly lowland formed of the basin of the Guayas and the coastal plain but in the south-east is a mountainous ridge called the cordillera de Colonche which is narrow and in the form of a half circle extends from near Guayaquil where it is named "cordillera de Chongon," to just south of Portoviejo where it is called cordillera de Puca. It is about 84 m. long and some times reaches 2,60o ft. altitude.

The "montanas de Cojimies" in the western part of the prov ince of Esmeraldas, lie between the Pacific and the Rio Quininde. These "mountains" are a narrow ridge about 35 m. long and reaching i,000 ft. altitude. Just south-east of the town of Esmer aldas is a narrow ridge called "montanas de Atacames." It is about 20 m. long and its summits attain an elevation of nearly I ,000 ft. above the sea.

Scarcely anything is known of the coastal region between the rivers. Esmeraldas province is supposed to be a tableland having summits of about ',coo ft. elevation and valleys dissected to nearly sea-level. The Guayas river and its tributaries form a large part of the coastal region. The river is in part an estuary extending north from the gulf of Guayaquil and is the largest navigable stream on the Pacific coast of South America. At Guayaquil to which sea-going vessels ascend it is about 2 m. wide. The river rises near the equator, and its main tributaries are the Daule, the Vinces, Rio Zapotal and Rio Chimbo, all navigable on their lower courses and having extensive swamp areas. Steamboats go regularly from Guayaquil up the Rio Bodegas to Babahoyo 8o m. above Guayaquil and for 4o m. up the Daule. The navigable channels of the Guayas and its tributaries are corn puted to be 200 m. long; the drainage basin is said to cover about 14,0DD sq. miles. The second large river system of the coastal region is the Rio Esmeraldas, which like the Guayas has tribu taries whose sources are in the snows of the Andean highlands. The Rio Esmeraldas is formed by the Guallabamba and Blanco about 42 m. from its mouth and discharges into the Pacific at i ° N. and 79° 40' W. through a narrow and precipitous gorge. The most northerly important coastal river system is the Santiago, formed by the Cayapas and the Santiago. The Cayapas is navi gable by canoe for a long distance, the Santiago for only a few leagues above its junction with the Cayapas. Below La Con cepcion, the Santiago is a broad, deep stream. Near its mouth it divides and forms many islands, chief of which are La Tola, Santa Rosa and San Pedro. The Mira, north of the Santiago, forms for a part of its course the boundary between Colombia and Ecuador.

Bays.—The coast extends from about i° 30' N. and 78° 52' W. to lat. 3° 30' S. and curves westward to 81 ° W. Most promi nent headlands are La Puntilla, Cabo de San Lorenzo, Cabo Pasado and Punta Galera. The bays are commonly broad inden tations with the exception of the gulf of Guayaquil, and the rivers discharging into them are generally obstructed by bars so that the small ports of the coast do not afford much protection to shipping. The most northerly of these bays is Ancon de Sardinas, lying south of the Mira delta. The head of the bay is fringed with islands and reefs behind which is the mouth of the Mataje, the boundary between Colombia and Ecuador, and that of the Santiago. The small bay of San Lorenzo would form an excellent port terminus for Quito. The coast for about 8o m. E. and W. of the mouth of the Esmeraldas consists of rocky promontories and of high cliffs broken here and there by short river ravines. The Esmeraldas has a wide mouth with islands and shoals constantly altered by the swift current. The port of Esmeraldas is on the left bank of the river. As the mouth is obstructed by a bar and the river current is swift, the anchorage for ships is outside in an open roadstead with slight protection. Between Cabo Pasado and Cabo de San Lorenzo is a broad indentation in which is the Bahia de Caraquez, a small bay, now the terminus of a railway which runs inland 47. m. to Chone. The southern portion of the broad in dentation is called Bahia de Manta and on this is a small port served by a railway extending inland 37 m. to Santa Ana. The Bahia de Santa Elena is formed by a broad curve from Punta Ayangue to La Puntilla. At Salinas a small settlement on the end of the point "La Puntilla" is the landing place of the All-America cable. A pipe line terminates on the shore east of Salinas bringing petroleum from the wells of the Anglo-Ecuadorian Oil Co., situated on the south coast of the peninsula. Ships anchor with little pro tection in the roadstead between Salinas and Ballenita. The gulf of Guayaquil is the largest on the Pacific coast of South America. Its mouth is 14o m. wide between La Puntilla on the N. and Cabo Blanco on the S. and it penetrates the land eastward with a slight curve northward at its head for a distance of about i oo m., termi nating in the Guayas estuary and river on which is the port of Guayaquil. The upper end of the gulf and its northern shores are fringed with swamps through which numerous estuaries pene trate for some distance inland. Of these, the Estero Salado, W. of the Guayas, formed of many shallow tide water channels pene trates as far inland as Guayaquil, but is used only by canoes. Near Guayaquil in the Estero Salado is good bathing. The upper end of the gulf of Guayaquil is filling up with the silt brought down from the Andes. It is divided midway by the large island of Puna, at the eastern end of which is the anchorage for steamers too large to ascend the Guayas. The steamship channel passes between this island and the Peruvian coast and is known as the Jambeli channel. The Morro channel, west of Puna, is obstructed by shoals and dangerous for shipping. In the Jambeli channel on the south-east shore of the gulf is the small port of Puerto Bolivar, serving Machala and the Zaruma mining district. A rail way runs inland to Machala and thence to Paraje. Another is being built from Puerto Bolivar via Santa Rosa to Zaruma.

Islands.

There are few islands off Ecuador, and only one of any considerable size, that of Puna in the north-east part of the gulf of Guayaquil. This is 29 m. long by 8 to 14 m. wide. Puna generally is low and swampy and its shores, except on the east, are fringed with mud banks. It is densely wooded, in marked contrast to the opposite Peruvian shore and is unhealthy the greater part of the year. It has a population of about 3,000, about Soo living in the village of Puna at its north-east extremity. Pilots are taken on here to ascend to Guayaquil. Twelve miles south west of Puna island and 8o m. from Guayaquil is Amortajada or Santa Clara island, whose resemblance to a shrouded corpse sug gested the name which it bears. It rises to a considerable eleva tion, and carries a light 256 ft. above sea-level. There are some low, swampy islands, or mud flats, covered with mangrove thickets, in the lower Guayas, but they are uninhabited. On the coast N. of the Gulf of Guayaquil there are only two small islands of more than local interest. The first of these is Salango, in I° 35' S., which is about 2 m. in diameter and rises to a height of 524 feet. It is well wooded, and has a well-sheltered anchorage formerly frequented by whalers in search of water and fresh provisions. The next is La Plata, in I° 16' S., which rises to a height of 790 ft., and has a deep anchorage on its eastern side where Drake is said to have anchored in 1579 to divide the spoils of the Spanish treasure ship "Cacafuego." The Galapagos islands (q.v.) belong to Ecuador, and form a part of the province of Guayas.

The Amazon Region.

The region east of the Andes moun tains or the Amazon region is called the "Oriente" and is entirely forested. It begins at the eastern base of the Andes mountains which may be taken at about 4,000 ft. above the sea and extends to the eastern boundary with Peru (see above on boundaries).The land surface in general slopes eastward, at first rapidly until at about 85o ft. above the sea it becomes a part of the Amazon lowland. Very little is known of the interstream areas. Immedi ately east of the Andes the general surface is deeply dissected by rivers, but in a measure as one proceeds eastward the land sur face tends in general to meet the level of the rivers. Near the Andes are here and there mountainous masses like the volcano Sumaco (12,70o ft. above the sea) and the cordillera Galeras which in reality belong to the Andean region for they are con nected to the Andes by the 4,000 ft. contour. A few detached mountain masses such as the Lumbaki mountains on the equator in longitude 77° 20' west of Greenwich are known to exist and doubtless others will be discovered later.

The main rivers of the Oriente originate on the Andes. All flow into the Atlantic and those whose sources are in the Andes emerge in great gorges on to the Amazon lowland. They are tor rential and not navigable till they reach a low elevation when they suddenly become navigable, not only for canoes, but for launches and steamers.

This uppermost point of navigation, or "fall line" is clearly marked. The streams for about 10o m. east of the Andes are torrential and full of rapids. Their courses in this part are usually "braided," i.e., choked with debris from the Andes so that there are many channels and islands. The beds are of boulders which decrease in size eastward. At the "fall line" which on the Rio Napo for example, is 85o ft. above the sea, in longitude 77° oo' W. of Greenwich, and about 3,00o m. from the Atlantic, the braided character disappears and the rivers become deep, sluggish and wide, with low mud banks.

Tributaries.

The streams are all tributaries of the Amazon (q.v.), divided into two classes, those which rise in the Andes and those which have their entire courses east of the mountains. In the first class are the Rio Napo, Rio Pastaza, Rio Santiago and Rio Chinchipe. To the second subdivision belong the Rio Tigre and the Rio Morona. The Rio Napo, the tributaries of which rise on the Andean slopes from Cotopaxi north to Tulcan, is the largest of these rivers. Its total length is about 700 m. and it enters the Amazon at about 385 ft. above the sea, in latitude 3° 20' S. and 72° 40' W. of Greenwich. From the village of Napo near the base of the Andes where it has an elevation of 1,580 ft. above the sea, it descends in 90 m. to an elevation of about 90o ft. above the sea, at the mouth of the Rio Coca. From here it drops 515 ft. in about 464 m. or about one foot per mile. In the stretch between Napo and the mouth of the Rio Coca, the river is shallow and canoes can be used, but going upstream against the current and with bad rapids, it is slow work, about i m. per hour. The de scent from Napo to the mouth of the Coca is done by canoe and by shooting the rapids, in two days, i.e., at the rate of about 5 m. per hour. At the mouth of the Coca, the Napo is about 1,50o ft. wide; at its mouth it is nearly one mile wide. Steam launches can ascend to a point several miles above the mouth of the Rio Coca. The principal tributaries of the Napo are the Aguarico and the Coca from the north, and the Curaray from the south. The Coca unites with the Napo in lat. o° 30' S. and 77° oo' W. of Greenwich and is about i 5o m. long. This river has been recently explored by Sinclair who finds that at Papallacta it is about ft. above the sea and at Baeza 20 m. farther east, 5,863 ft. having a fall of about 223 ft. per mile in this distance, a total of 4,47o ft. About 50 m. farther east the Coca debouches from deep can yons on to the lowlands and for the remainder of its course, 54 m. it is a shallow, braided stream of strong current with many islands and channels. Its average fall in the lower 54 m. is 18 ft. per mile and although the current is swift and there are many danger ous rapids, canoes can be poled 5o m. above the mouth.The Rio Aguarico joins the Napo about 312 m. from its mouth and about 590 ft. above the sea, and is about 20o m. long. Little is known about its course or the country through which it flows. A part of the river near its source forms the boundary between Ecuador and Colombia.

Th main tributary of the Napo from the south is the Rio Curaray. This stream rises east of the Andes 18 m. north of Canelos, in hills about 2,000 ft. above the sea. It is about 400 m. long and joins the Napo about 143 m. from the Amazon. Near its headwaters it is a creek with a very serpentine course and it is described as having this feature all the way to its mouth. It is said to be navigable on account of its sluggish current as far as Canonico about 30o m. from its confluence with the Napo. Sin clair crossed it in 1921 in long. 77° 40' W. of Greenwich and gives its elevation there as 2,000 ft. above the sea with a fall of about 5 ft. per mile.

The Rio Pastaza which is about 45o m. long enters the Amazon at a point 76° 20' W. of Greenwich and about 4° 55' S. lat. The upper portion of this river, 127 m. long lies on the Andean high lands and has been described above as far as Mera, 3,8o8 ft. above the sea where the river enters the Amazon lowland. From Mera the river drops at the rate of 4o ft. per mile to the mouth of the Rio Pindo (2,70o ft. above the sea), where it is still a very tor rential stream. Apparently the river is not navigable for canoes above Andoas, a settlement about 68 m. below the Pindo, for the usual route of Indians and travellers eastward leaves the Pastaza near the mouth of the Pindo, to proceed overland to Canelos (1,690 ft. above the sea, in lat. I° 35' S. and 45' W. of Green wich) on the Rio Bobonaza where canoes are taken to its conflu ence with the Pastaza at Andoas, a point about 216 m. from the Amazon. It is said that boats of a draft not exceeding 4 ft. may ascend about i i o m. from the Amazon.

The Tigre is an affluent of the Amazon and rises east of the Andes. Its length is a little over 400 miles. It joins the Amazon in 55' W. of Greenwich and in 4° 20' S. lat. It is navigable for boats drawing 6 ft. at high water from the confluence of its tributaries, the Cunambo and the Pintuyacu, to its mouth, a dis tance of about 400 m. About 104 m. from its mouth it receives the Rio Corrientes, an affluent from the west which is navigable for about ioo miles. The Rio Pucacuru joins it from the north about 152 m. from its mouth and this latter stream is navigable it is said for about 37 m. above its mouth. The width to the mouth of the Corrientes is 65o to 98o ft. and its depth from 25 to 3o feet. The current is said to flow at about I2 m. per hour. The ascent of 400 m. can be made in about 67 hours, there being only two bad places, the Island of Tacuma and at Piedra Lisa.

The Morona is an affluent of the Amazon, whose course is also entirely on the lowlands east of the Andes. Its sources are to be in the Rio Cumasi and other streams north of Macas at elevations of about 4,000 ft. above the sea. Its length is about m. It joins the Amazon at 485 ft. elevation in longitude 770 02' W. of Greenwich and 4° 45' S. lat. It is a very meander ing river and at 243 m. from its mouth is only 66o ft. above the sea; 203 m. farther down its elevation is 515 ft. and the fall is thus only 144 ft. in 203 miles. From here to the mouth, 41 m., the drop is only 3o feet. It is navigable from its mouth to the Man hauasisa, 310 miles upstream at all times and for two-thirds of its length by steam launches drawing 4 feet. Its depth is from 4o to 5o feet and its width from 26o to 490 feet.

The Rio Santiago empties into the Amazon in 77° 38' west of Greenwich and 4° 25' S. lat. at an elevation of 58o ft. above the sea. Its mouth is just above the Pongo de Manseriche. Its total length following the tributary, Rio Zamora is 281 m., the Rio Zamora being 15o m. long. From Macas, 3,58o ft. above the sea, on the Rio Upano, to the mouth of the Santiago, 58o ft. elevation, the distance is about 182 m. and the drop 3,00o ft. i.e., about 16 ft. per mile.

The Rio Chinchipe is about 88 m. long and is almost entirely in the Andes. It joins the Amazon in 5° 27' S. lat. and 78° 32' west of Greenwich at an elevation of about 1,209 ft. (J. H. SR.) Geology.—The Andes reach great heights in Ecuador, where they include several lofty volcanic peaks. The volcanoes are of Tertiary or later origin and are most numerous in the northern half of the country. Cotopaxi, Chimborazo and Cayambi are vol canoes that rise more than 19,00o ft. above sea-level, and these and other snow-covered and ice-capped peaks form the culminating points of the mountain mass. This has been divided into the Eastern Cordillera, composed of gneiss, mica schist and other old crystalline rocks, and the Western Cordillera, composed of por phyritic eruptive rocks of Mesozoic age and of Mesozoic sedi mentary beds, mainly Cretaceous. Between these ranges are recent deposits that contain plant remains. Northward this depression is in large part filled with lava, tuff and agglomerate from the vol canoes, which stand either upon the folded Mesozoic beds of the Western Cordillera, on the old rocks of the Eastern Cordillera or on the floor of the depression. The lavas and ashes are mostly Andesitic. Ecuador is more subject to volcanic disturbances than any other South American country.

At the eastern base of the Andes is a widespread series of Upper Cretaceous beds of sandstone, black shale and limestone, which lie nearly horizontal and are only slightly disturbed. The lime stone is highly impregnated with bitumen. Most of the country between the Andes and the sea is covered with Tertiary and Quaternary deposits, but the range of hills that runs north-west ward from Guayaquil is formed of Cretaceous sedimentary and porphyritic rocks like those in the Andes.

Gold, silver, platinum, copper, mercury and lead are mined. Some oil is obtained from wells sunk on the Santa Elena penin sula, in the province of Guayas, in south-eastern Ecuador. In 1926 the production of oil was 214,00o bbl. ; in 1927 it was 450,00o barrels. (G. McL. Wo.) Climate.—Were it not for its lofty mountains and the Hum boldt current the climate of Ecuador would be entirely tropical, for it is traversed by the equator. But, inasmuch as the elevations extend from sea-level up to 20,576 ft., the climates vary from the tropical of the lowlands east and west of the Andes, through the temperate of the higher slopes, to the Arctic climate of the peaks of Chimborazo, Cayambe, Antisana, etc.

The tropical lowlands are along the Pacific coast and the tribu taries of the Amazon, east of the Andes. The former are com paratively dry ; the latter extremely humid because of the Atlantic trade winds in their south-west course across the low and ex tremely wet basin of the Amazon.

The Pacific coast is one of transition between the arid climate of the coast of Peru to the south and the northerly humid one of Colombia. The former climate is caused mainly by the presence of the Humboldt current which flows from the coast of Chile north, and the latter by the warm south-flowing waters of the Central American current. These two currents, with a, difference of temperature of from 6 to 8° F, meet off the coast of Ecuador and flow west to the Galapagos islands. Only at rare intervals is their relative strength altered, as in 1925 when the Central American current flowed farther south than had ever been known and the Humboldt current appeared to be missing entirely. Conse quently the deserts of Peru and of southern Ecuador were visited by large quantities of rain for the first time in many years. The Santa Elena peninsula, for example, received a rainfall in the period Jan. 25 to May 1, 1925 of 4o in. and this decreased in the period Jan. 11 to April 5, 1926 to 27 in. and in the 12 months of 1927 to nearly normal, viz., a total of 4 inches.

Under normal conditions, the inner shores of the gulf of Guayaquil, the island of Puna, the valley of the Guayas and all the coast of Ecuador north of Cape San Lorenzo have consider able rainfall, while the coast from the Santa Elena peninsula north to Cape San Lorenzo, including the island of La Plata, is a region of scanty rainfall. From Cape San Lorenzo south there appear to be four climatic provinces. In the Montecristi region the climate is normally semi-arid but the hills receive a typical heavy Scotch mist. In the cordillera de Colonche, a ridge about 1,800 ft. high south of the above region, there is more humidity and very thick vegetation. In the Santa Elena peninsula there are no hills and the climate is extremely arid. Finally along the shore of the gulf of Guayaquil south-east from Santa Elena the climate is tropical with luxuriant and profuse vegetation. The Santa Elena climate is characteristic of the arid type. In 1927 the maximum temperature averaged 86.3° F, the minimum 65.4° F. The hottest months were Jan., Feb., March and April. The total rainfall for the year 1927 amounted to 4 in. and took place in the months of February and March.

No rainfall data are available for the humid part of the coast north of Cape San Lorenzo. At Recreo, a humid region on the coast in o° 27' S. there was (July 1893–June 1894) a mean annual temperature at 6 A.M. of 7 2.3 ° F, at noon 7 7.1 ° F, at 3 P.M. 7 ° F and at 8 P.M. 74r° F, the average for the year amounting to 7 5 ° F. At another point on the coast in the humid zone, viz., La Maria 54' S.) on the east coast of the Jam beli channel, north of Machala, the averages for the period Jan uary to May 1892 were: 6 A.M. 74.4° F, noon 82.8° F, 4 P.M. 8 5.8 ° F, 8 P.M. 81.3° F, the average being 81.1 ° F. At Guayaquil, which is 33 m. above the entrance of the Guayas river into the gulf, the mean annual temperature varies between 82° and 83° F and the rainfall for February and March 1882 is reported as being 3.1 and 6.1 in. respectively.

There seems to be a clearly marked division in the Pacific coastal region into cooler months from July to November and warmer months the rest of the year.

The tropical region east of the Andes is the zone of greatest rainfall. The average minimum temperature at Mera on the Pastaza (3,80o ft.) for the years 1923, 1924, 1926 and 1927 was 5 7.7 ° F; the average maximum 79.9 ° F and the mean annual temp. 68.8° F. The rainiest months were May in 1922, 1924 and 1925 and April in 1923 and 1927. The heaviest rainfall in any month was in April 1927 with 27 in. and the driest month was Feb. 1923 with 4.8 inches. There are few weather stations in Ecuador and figures of average, maximum and minimum rainfall through the whole country vary greatly in the different regions, coastal belt, the plateau and the eastern lowlands.

There does not appear to be any pronounced division into rainy and dry seasons. At Tena (1,70o ft.), another point east of the Andes, observations during 1925-27 show an average yearly minimum temperature of 65.3° F and an average maximum of 81.3° F. The mean annual temperature here is about 73.3° F. The rainfall in 1925 totalled 147.2 in. (12.2 ft.). Eleven months of observations in 1926 gave a total of 6.66 in. per month, which would be equal to a total of 8o in. for the year. But during the period Jan. June 1927 there was a total of 107.2 in. averaging 18 in. per month, which if continued the entire year would amount to 201 inches. The best series of observations, and in fact the only ones available to show the climatic conditions in the temperate zone of the Andes is that for which we are indebted to Mr. J. W. Mercer of the South American Development Co., owners of the Zaruma mines, 2,50o ft. above the sea. These observations carefully made over a period of 3o years (1897 1927) show an average daily minimum temperature of 64.4°, an average daily maximum temperature of 81.5° F. In addition, the records for the hour 8 P.M. show for the 3o years an average temperature of 69.8° F. The hottest temperature recorded was F, the lowest 51° F. The average temperature for the 30 years is 72.9° F. The rainfall takes place almost totally in the months from December to May. The average yearly total for the 3o years is 66.9 inches.

Flora.

The flora varies from that of the tropics to that of icy mountains; from vegetation characteristic of humid and arid regions on the Equator to lichens on the snows at 18,400 ft. above the sea. Corresponding to the broad climatic divisions the vegetation is classified into five types : (I) that of the arid regions on the low-lying Pacific coast; (2) that of the humid regions on this same coast and in the low-lying Amazon region east of the Andes; (3) that of the forests on the east and west slopes of the Andes up to about io,000 ft. altitude; (4) that of the so-called "cereal" zone, a treeless region on top of the Andean plateau ; and (5) the "paramo" or Alpine region which terminates in the region of perpetual ice and snow. Because of this great diversity of climate, the flora of Ecuador is exceedingly rich, and species before unknown from this region are constantly being discovered. J. N. Rose has recently raised the number of known species of cacti from 12 to 3o. Hitchcock has extensively studied the grasses which extend in great diversity from the lowlands to the snow line. W. Popence has recently described about loo species of fruits. Ferns are abundant and of many types ranging from the filmy ferns of the fog-covered forests to the giant tree ferns of the tropical valleys. The genus Eupatoriusn occurs in many forms, more than 5o species being reported. Numerous species of the heath family are found in the forested mountains and the high paramos.

Among the more common economic plants are the corozo or ivory-nut palm (Phytelephas macrocarpa), which furnishes vege table ivory for manufacturing buttons; the cocoa tree (Theo broma cacao), from which the cocoa bean is gathered; the fibre plant Carludovica palmata (not a palm), used for making "Panama" hats, the balsa tree or corkwood (Ochrorna lagopus), furnishing the lightest timber (3o lb. per cu.ft.) in the world; and the cinchona tree which yields quinine. Wheat grows at elevations of from 4,500 ft. to 9,80o ft. and barley up to 11,500 feet. More than loo kinds of useful woods have been described.

Mammals.

While in general mammals are comparatively scarce, according to Tate they are represented by a very wide range of species. In the forests east of the Andes the Primates are numerous, but on the west coast only three genera occur: spider-monkeys, howlers and capuchins. The Carnivora include the jaguar, puma, ocelot, foxes, weasel, Tayra, otter, skunk, grison, racoon, coatimundi and kinkajou. The Ungulates comprise the tapir, two kinds of deer and two sorts of peccaries. Among the rodents are the amphibious capybara (east of the Andes), paca, agouti and the rare Dinomys; the smaller forms include squirrels, rabbits, cavies and numerous rats and mice. There are numerous species of bats, including the blood-sucking vampire. Represent atives of the sloths, anteaters and armadillos are not rare. The opossums, with half a dozen genera, include the web-footed Chi ronectes, and the curious little Caenolestes, the so-called "living fossil," of the high Andes.The chief governing factor in the distribution of these animals is the Andes Mountains which run north and south through the country causing wide variations in the climate. Broadly speaking the climates are tropical from sea-level up to 5,000 ft.; subtrop ical from 5,000 to ii,000 ft.; and temperate, from 11,000 ft. up to snow-line. These conditions, modified by rainfall, act directly upon the vegetation and the animal life within the several zones, resulting in the evolution of specially adapted forms. The only indigenous animals under domestication are the llama and alpaca. Neither is abundant. But horses, cattle, sheep, goats and pigs are now raised everywhere. In the high plateaux, sheep and cattle thrive particularly well. A whaling enterprise, the Compania Bal lenera del Ecuador, operating from Santa Elena, was started in 1925. In 1926, according to a report of the U.S. Consul, a catch of 37o whales was made which yielded 9,500 barrels of oil.

Remains of extinct vertebrates, such as mastodons and horses, are found in the Pleistocene deposits of the highlands and also of the Pacific coast. The natives at the time of the arrival of Pizarro, in 1527, ascribed these to a race of giants which formerly inhab ited the country.

Birds.—Dr. Frank Chapman states that about 1,500 species of birds have been found in Ecuador. This is approximately one fourth of the South American avifauna and is doubtless a larger number of birds than has been recorded from any other area of similar size. Ecuador owes its exceptional abundance of bird life primarily to the extent and altitude of its mountains, which add to the lower or Tropical Zone, three additional zones, each of which has species that are restricted to it (endemic). They are the Sub-tropical Zone (alt. from 3,000 or 4,00o ft. to 9,00o ft.) with 237 species, the Temperate Zone (alt. 9,000-12,000 ft.) with 142 species and the Paramo Zone (alt. 12,000 ft. to snow line) with 33 species. These endemic zonal species have been derived from the Tropical Zone at the base of the Andes and also from both the south Temperate and the north Temperate Zones. Their existence affords an admirable illustration of the stimulating effects of change of environment on the evolution of species. For example, Ecuador is known as the land of humming birds, but it is not generally realized that only 66 of its 147 species are found in the Tropical Zone, while 81 are confined to the upper life zones and in large part at least, have therefore been evolved since the latter part of the Tertiary when the mountains they occupy were elevated.

The brilliantly coloured Tanagers (Tanagridae) are also com monly considered as characteristic of the American tropics, but of the 1o6 species found in Ecuador only 52 are known from the Tropical Zone, while 46 are confined to the Sub-tropical, and 18 to the Temperate Zone. Other families of birds with numerous species in Ecuador are the Pigeons (Columbidae) 26 species; Parrots (Psittacidae) 38 species; Toucans (Rhampastidae) 19 species ; Woodpeckers (Picidae) 37 species ; Antbirds (Formi cariidae) 114 species; Woodhewers (Dendrocolaptidae) 31 spe cies; Flycatchers (Tyrannidae) 16o species; and Wrens (Troglo dytidae) 32 species.

Sixty-six species of birds that nest in North America visit Ecuador in winter. Among this number are the Carolina Rail, or Sora (Porzana carolina), Blue-winged Teal (Querquedula dis cors), Kingbird (Tyrannus tyrannus), Barn Swallow (Hirundo erytlirogaster), Red-eyed Vireo (Vireosylva olivacea), Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla), Rose-breasted Grosbeak (Zamelodia ludo viciana) and Scarlet Tanager (Piranga erythromelas).

Fishes.

When compared with the Amazonian fauna, the freshwater fish fauna of the Pacific slope of Ecuador (see C. H. Eigenmann, Mem. Carnegie Mus., vol. ix., pp. 1-35o), is rela tively meagre, only about 6o species being included. The fishes of the eastern part of Ecuador are as yet practically unknown. Although the species and many genera are now different, all of the fishes of the Pacific slope streams are similar in character to their Amazonian relatives and were evidently derived from them before the uprising of the Andes. This Pacific slope fauna is characterized by the lack of certain usual Amazonian types such as the electric eel and the piranha. One of the most remarkable of Ecuadorian fishes according to Dr. Henn of the Carnegie Museum is the "raspabalza" (Plecostomus spinosissimus), which is a sort of plated catfish, so well protected by its spiny cov ering that, if care is taken not to frighten it, it may be picked up by hand from the sandbars. In the same waters, the Guayas sys tem, occurs a blind catfish, the "ciego" (Cetopsis occidentalis), the eyes of which are covered with thick skin.Another celebrated Andean species found in Ecuador is the so-called volcano fish (Astroblepus grixalvii), which, by means of its disk-like, sucking mouth and prickly fins, is enabled to live in torrential mountain streams. Formerly this fish was errone ously said to be thrown in great quantities during eruptions from subterranean lakes within volcanoes.

Reptiles.

All the major groups of reptiles are known. Accord ing to Ruthven there are fresh-water and land turtles, crocodilians, lizards and snakes. Among the lizards, the beautiful "fan-lizards," "American chameleons" or Anoles are conspicuous for their delicate changeable colours and flashing throat fans. Other interesting lizards are the Ameivas, active and conspicuous on bright warm days; the blind lizard, Acophisbaena, frequently found in ant and termite nests ; the spiny Echinosaura ; and sev eral geckos. The snakes of Ecuador vary in size from thread-like Helminthophis, which burrows in decaying wood, to the large boa (Constrictor constrictor). There are fresh-water snakes, sea snakes, tree snakes, ground snakes and burrowing snakes. Many are harmless, but there are numerous venomous species. Among the '-3tter are several opisthoglyph snakes, several protoglyph snakes, coral snakes (Elaps or Micrurus) and the dangerous solenoglyph pit-vipers, notably the fer de lance (q.v.). There are also various tree snakes, such as Oxybelis, interesting for their attenuated form and habit of resembling vines. The crocodilians are represented by a true crocodile and the broad-snouted caiman. A few fresh-water turtles and the large land tortoise (Testudo denticulate) are known.Insects.—While the insect inhabitants of Ecuador embrace numerous genera and species representing the most important orders, no comprehensive survey has been completed. Campos enumerates some 1,55o known species, chiefly butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) ; beetles (Coleoptera) ; grasshoppers and their allies (Orthoptera) ; and bees and ants (Hymenoptera). Of beetles alone there are estimated to be 8,000 species. In general it may be said that for each 1,50o ft. of elevation there is a new province of insect life. Lepidoptera have been collected on the slopes of Antisana at 16,000 ft. altitude. A giant beetle (Dynastes hercules) attains a length of five inches. Certain click beetles and fireflies are noted for their phosphorescent light. Among the Dip tera is found or rather was found the mosquito Aedes argenteus, the carrier of the yellow fever germ, known also as Stegomyia fasciata. Below 1,50o ft. elevation also occurs the mosquito (Anopheles albimanis) carrier of the malaria germ. Numerous parasitic insect pests abound among the Indians.

Population.

No complete census has ever been made. The total population is variously estimated at between II and 2 mil lions, composed of three elements, pure white, pure Indian and combinations of the two, called mestizos. The relative proportions are unknown. Recent estimates in Peru where the population is very similar in composition to that of Ecuador are: whites 13.8%, Indians and mestizos 24.8%. The deaths in Ecuador in 1919 and 1923 respectively totalled and 46,149 and the births 70,397 and 82,222 (both excluding children born dead). Such figures as there are show that Guayas is the most populous province and next in order are Manabi, Pichincha, Chimborazo, Azuay and Tungurahua. The languages of the whites and mestizos is the Spanish ; that of most of the Indians is the Quechua. In the forests east of the Andes, the Jibaro language is used by a number of Indians and west of the Andes a few Indians speak Cayapa-Colorados.Recently an attempt has been made to attract European immi grants, and a few Austrians came in. White immigration to the east of the Andes has been a failure, as has Norwegian colonization in the Galapagos islands. There is, however, great possibility of success in bringing European immigrants to the highlands, as the climate is very suitable and healthful.

Government.

Ecuador is a republic with the power divided between the legislative, executive and judicial branches. The constitution is the supreme law; it may be reformed by a majority of the senate and deputies.Congress is supposed to convene each year on Aug. To. The senate is composed of two senators elected from each province.

The house of deputies is formed of a deputy for each 30,000 inhabitants, elected by the provinces; but any province without sufficient population may elect a deputy. In the 1925 Congress there were S4 deputies.

The president, whose term is four years, is elected by the people. He names his ministers, whose departments are the in terior, foreign relations, public instruction, public welfare, treas ury and war, marine and aviation. The duties of these ministries are determined by the constitution and special laws of Congress. In 1928 the Ministry of the Interior had charge of the administra tion of the various provinces, including the Galapagos islands and excepting the two provinces of the Oriente, through the gov ernors, Jefes Politicos and Tenintes Politicos. It also had charge of the civil register, national, rural and railway police, jails and public works. The Ministry of Public Instruction supervised all schools, universities, colleges, etc., the postal service, telegraphs and wireless service and national telephones.

The Ministry of Social Welfare is in charge of agriculture, public help of the poor, sanitation, hygiene, fire prevention, immi gration, colonization, statistics, public lands and the administra tion of the Oriente or eastern Ecuador. The minister of Hacienda, or treasury, directs the customs, mines, the budget, banks and the controller general's department.

The judicial branch of the Government consists of the supreme court which sits at Quito with five minister judges, one minister fiscal and five assistant judges and the superior courts, of which there are six (at Quito, Guayaquil, Riobamba, Cuenca, Loja and Portoviejo). In addition there are 16 Juzgados de Letras. These are in nearly every province.

There are 17 provinces 67 cantons and 498 parishes. Each province is ruled by a governor, each canton by a Jefe Politico and each parish by a Teniente Politico.

The Galapagos islands are under a Territorial Chief. The Oriente is divided into the two provinces of Napo-Pastaza and Santiago-Zamora.

Army, Navy and Aviation.

In 1928 the army consisted of 5 generals, 12 colonels, 44 lieutenant-colonels, 89 sergeant-majors, 162 captains, 219 lieutenants and 134 end lieutenants. The "tropa" or troops consist of 434 end sergeants, 491 "Cabos primeros," 422 "Cabos segundos" and approximately 3,429 privates. Military service is compulsory for men after 20 for one year. All are then a part of the reserves to the age of 45. There is a mili tary school in Quito conducted by 5 civil professors and by officers. There is a military hospital in Quito and another in Guayaquil. In 1922 an Italian military mission began the re organization of the national army. The 1928 budget for army, navy and aviation was about $1,811,375, or 17% of the total income. There are in all S3 officers and about 264 sailors in the navy. It has one gunboat. In aviation a beginning has been made.

Religion.

Of the pre-Inca religions the only one remaining is possibly that of the Jibaro Indians of eastern Ecuador, which Karsten says is wholly unaffected by Christianity. In this there is no notion whatsoever of a supreme being and creator of the Universe, but it is by no means a pure demonology. The Inca religion has apparently entirely disappeared (see INcA).The Spaniards made the conquest of Peru not only a territorial extension of their power but a means of conversion of the aborigines to the Roman Catholic religion. The capitulation of July 26, 1529 made Hernando de Luque bishop of Peru, and Pizarro, when he returned from Spain after having made this contract, took with him a number of Dominican priests. Among them was Fray Vicente de Valverde, who, when Atahuallpa, the last Inca king, was condemned to be burned to death, mercifully had his torture changed to hanging on Atahuallpa's consenting to accept the Christian religion. Soon more priests, this time Merce darians, arrived and the campaign to convert the Indians was well started. Luque never went to Tumbez to take over his charge but Valverde was made bishop at Cuzco over all of Peru. Gonzalez Suarez states that by the end of the 17th century there were in Ecuador alone 42 convents belonging to the Dominicans, Franciscans, Augustinians, Mercedarians, Jesuits and barefooted Carmelites. The number of priests was very large, Quito alone having as he states about i,000 priests. Great discord reigned and "great damage was caused to the moral advancement of the people by the bad example not only in lack of virtue among the priests, but by their lack of good manners." Gonzalez Suarez concludes, however, that the convents were the cradle of culture. It is certain that, by the end of the 17th century, no part of the Andean region remained unvisited by the missionaries. In 1767 the Jesuits were expelled from all the Spanish dominions in America.

The opposition to the official religion was probably to restrict clerical influence in political affairs. The growth of liberalism re sulted in 1889 in the church tithes (io% of the value of the pro duction of the farms) being abolished; a tax of 3 per mill on the value of the farms was substituted. In 1902 civil marriage was permitted and in 1904 the Church was placed under State control, the foundation of new religious orders was forbidden and new religious communities were denied entrance. In addition all mem bers of the episcopate had to be Ecuadorians. The State took over the landed property of the religious orders and administered it under a board of charities which now gives a pension to the friars. The excuse for this latter action was stated to be the great wealth of the church, gained largely through participation in legacies and by labour which received no "earthly" pay.

In recent years a few Protestant missionaries have penetrated the country and are at work among the Indians east of the Andes (Tena and Macas). There is now absolute freedom of religion in Ecuador. The Catholic Church has an archbishop at Quito and bishops in Ibarra, Riobamba, Cuenca, Guayaquil and Portoviejo.

Education.

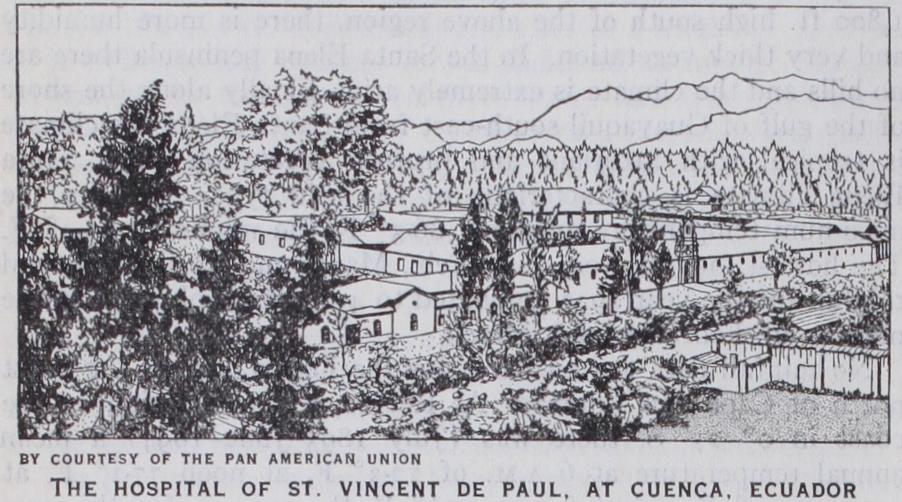

The Ministry of Public Instruction exercises supervision over all educational institutions whatsoever.The superior schools are the Universidad Central of Quito to which is attached the Escuela de Enfermeras (nurses), the as tronomic and meteorological observatory of Quito, the Escuela de Artes y Oficios of Quito, the Universidad de Guayaquil, the Universidad de Cuenca and the Junta Universitaria of Loja. The Central university of Quito has facilities of medicine, science, law and archaeology. There are 49 professors. In 1924 there were 304 students. The Escuela de Artes y Oficios (school of trades) at Quito is now annexed to the faculty of science of the university. It is co-educational as is also the university. The Universidad of Guayaquil has faculties of medicine, law and dentistry, com prising 34 professors. In 1924 there were 197 students. The Universidad de Cuenca consists of faculties of medicine and of law and a professor of lithography, a total of 24 teachers. In 1924 there were 147 students. The Junta Universitaria of Loja has six professors and (1924) 22 students, all in law. The astro nomical observatory has a university professor as director.

There are 14 secondary schools with an enrolment of 2,007. In these, instruction is free, but attendance is not obligatory. In the primary schools attendance is compulsory and free for both sexes. In 1924 their enrolment was 112,219 children. The institutions of special education include : in Quito, the Juan Montalvo normal institute for boys and the Manuela Carizares with 14 teachers; the Rita Lecumberri normal institute for girls in Guayaquil, 16 teachers; the Pedro Carbo commercial school of Bahia; the Artes y Oficios trade school of Tulcan; the Orphans Trade school at Portoviejo and the National Conservatory of Music and Decla mation, Escuela de Bellas Artes, National Library and National Theatre, all in Quito.

The chief private secondary schools are the Jesuit's colleges in Quito and Riobamba ; the Cristobal Colon, Tomas Martinez, Juan Montalvo colleges in Guayaquil; and Dominican, the Mercedarian and Christian Brothers schools in various parts of Ecuador.

In addition to the National library at Quito are municipal li braries such as those at Quito, Guayaquil and Riobamba.

Railways.

There are 9 railways in Ecuador, with 410 m. in operation. Six of these are constructed, owned and operated by the Government. The others are privately controlled. There are two cities with street railways (see QUITO and GUAYAQUIL).The largest and most important of the railways is the Guayaquil and Quito (278 m.), which was completed by an American syndicate on June 25, 1909, at a cost of $59,000,000 or an average of per mile. The railway at one place attains an eleva tion of 11,653 ft. and presents a magnificent scenic route. Recently the Government through the acquisition of stock has obtained control of the railway. The next longest line in operation is that between Bahia de Caraquez and Chone, on the Pacific coast. This is 471 m. long and was constructed in the period 1909-12, under a contract between the Government and the Compagnie Francaise des Chemins de Fer; this provided for the construction of the line to Quito, an estimated distance of 217 miles.

The Ferrocarril al Curaray runs (21 m.) between Ambato and Pelileo. It is operated by the Government. The railway between Puerto Bolivar and Pasaje is 16 m. long with a gauge of 42 in. and is paralleled for a short distance by the narrower gauge Puerto Bolivar-Loja railroad. This also was constructed and is owned by the Government. In addition, a railway is being con structed from Sibambe, a station on the Guayaquil and Quito rail way, 8o m. from Guayaquil toward Cuenca. This when completed will be about 82 m. long. Another railway is under construction by the Government from Quito north to San Lorenzo (231 m.) . The Central railway of Ecuador operates between Manta on the Pacific coast and Santa Ana, a distance of 37 miles. Another is being constructed from Puerto Bolivar on the east coast of the Jambeli Channel toward Loja, via Santa Rosa, Arenillas, Pinas and Zaruma. In 1928, trains were being operated as far as Arenillas, 31 m. from Puerto Bolivar. The Government is also construct ing a railway from Guayaquil to Salinas, on the Pacific coast about 109 m. west.

With the exception of the Guayaquil and Quito Railway com pany's telegraph and telephones, all the mail service, telegraphs, wireless and telephones of Ecuador are directed by the Ministry of Public Instruction. In 1928 there were 256 post offices, 166 national telegraph stations, six wireless stations at Quito, Guaya quil, Puna, Machala, Bahia and Esmeraldas, and 24 national telephone stations. In 1926 official reports stated there were 4,261 m. of telegraph wire in operation.

Revenues.

The revenues of the republic as shown by the 1928 budget amount to $10,317,600. The most important sources of income are: Import taxes $3,000,000; alcohol monopoly $1, 300,000; export taxes $1,200,000; tobacco monopoly $600,000; taxes on consular fees $600,000 ; taxes on farm property $440,000; sales tax $420,000; salt monopoly $400,000; income tax $313,200; tax on liquors, beer, etc. $225,000; tax on alcabalas $220,000 and match monopoly $200,000.As extraordinary income is the loan of the Swedish Match Co. of $2,000,000 plus the compensation paid by this concern to the workmen of the Mercados factory. In addition there were $700,000 profits from the recoinage of the money. A new cus toms tariff went into effect on July 1, 1926.

Expenditures.

The largest items of expenditure of the na tional income as shown by the 1928 budget are, in order of size: Construction of public works, $2,000,000, ministry of war, $1, public instruction, $1,371,258; external debt, $533,959; customs (mostly salaries) $524,596; national police $426,911; internal debt $410,000; municipal sanitation $400,000 and diplo matic service $240,726.Extraordinary expenditures for 1928 were the purchase of 8o,000 shares of the Banco Hipotecario del Ecuador for $1,600,000 plus $165,490 for payments necessary for the establishment of the match monopoly, plus $700,000 for extraordinary amortization of the debt to the central bank.

Public Debt.

The total public debt as acknowledged by the Government in power in 1928 amounted to $25,949,725 distrib uted as follows: first mortgage railway 5% bonds, principal and back interest $18,882,680; salt certificates, as per contract of Sept. 30, 1908, principal and back interest $604,949; condor bonds, issued in partial payment of the old (1830) external debt $565,205; Swedish Match Company loan of 1928 $2.000,000 and internal debt $3,896,891—a total of Practically all of the foreign debt ($19,487,629) is due to the construction of the Guayaquil and Quito railway.was on a gold standard, adopted in 1898, until 1912, when payments in gold were stopped by decree. Although the bank-note circulation increased to a con siderable extent after 1914 (41,698,991 sucres on Aug. 10, 1927) the exchange rate was maintained with very light fluctuations at about the legal parity of $0.4867 to the sucre, until in the middle of 1918 it declined in value to 35 cents U.S.A. This situation was due to the effects of the war and to the passage of the "law of the inconvertibility of bank notes" which was really a moratorium. This law probably saved the banks, particularly the Banco Comer cial y Agricola of Guayaquil as it absolved them from paying gold for their notes, but certainly did great injury to the country at large. In Nov. 1918, the sucre suddenly rose in value to 45 cents and held this to the beginning of 1920 when it was quoted at 474 cents. The exchange market then broke suddenly and the sucre depreciated in value until it reached 184 cents, when, by executive decree of Nov. 16, 1922, the Government took over the monopoly and complete control of all foreign bills of exchange, fixing the rate of exchange at about 47 cents. This rate was afterward changed by the Government to about 33 cents and ultimately to 25 cents where it remained the official rate until the abolition by Congress in 1924 of the Government exchange commission. Contrary to expectation, upon the abolition of the control, exchange slowly declined till in 1925, the sucre had a value of 25 cents. But the sucre soon depreciated till in June, 1926, it reached the low value of about 16 cents; then, on the recommendation of the American Commission of financial ad visers, the sucre was stabilized at 20 cents gold U.S.A. The mone tary system was fundamentally reformed by a law creating a central bank and by a monetary law, both of which were approved and issued on March 4, 1927. By these provisions the monetary unit is the sucre of too centavos, equivalent to 20 cents U.S.A. Twenty-five sucres make a condor. Ecuador has fully returned to the gold-exchange standard. The Banco Central is under obli gation to pay all outstanding bank-notes in gold or in sight drafts on New York or London or in the new bank-notes of the central bank. The Banco Central of Ecuador opened on Aug. i o, 1927; it has the exclusive right to issue notes and possesses all the gold reserves of Ecuador. It must maintain a reserve of 50% of its circulation and deposits combined. The legal reserve on Dec. I, 1927, stood at over 66%. The member banks included in the central bank system number 21 with an aggregate capital and reserves of over 33 million sucres.

Foreign Commerce.—The foreign trade of Ecuador in 1926 amounted to of which imports totalled $10,460,682 and exports $13,987,065. Guayaquil received 91.8% by value of the imports and shipped 71% by value of the exports, the balance passing through the ports of Manta, Bahia de Caraquez, Puerto Bolivar, Esmeraldas, etc. All the foreign commerce is handled by foreign vessels. Guayaquil is visited by the steamships of nine European lines, and by vessels plying only on the Pacific coast.

The most important product is cocoa, which is grown on plan tations in the Guayas and Machala regions. Owing to the "witch broom" and "monilia" diseases the 1926 crop was the smallest since 1907. Cocoa exports in 1926 were 47,893,672 lb., or 4i% of the world's total production; the value was $5,874,687 or about 42% by value of the entire export trade of Ecuador. The period of greatest production of cocoa in Ecuador was 1916 when 668 lb. were produced, or 15% of the world's production. Coffee is produced on the lower western and eastern slopes of the Andes and is of excellent quality. In 1926 about 20,280,000 lb. were produced; 13,360,516 lb. valued at $2,559,891 were exported. Coffee is looked upon as a likely substitute for cocoa and extensive new plantings are being made. The tagua or vegetable ivory ranks third among the products. It is gathered from a tree called the elephant plant which is found in humid forests. The exports of these nuts amounted in 1926 to 38,581,441 lb. valued at $1,357, 143. "Panama Hats" are made to the value of $1,233,910. They are manufactured from the Carludovica palmata, a plant which resembles a palm, but without a trunk, and whose leaves rise from the ground fan-like and furnish the fibre for the hats. The in dustry has been limited entirely to the coast where the plant is native. A small amount of the fibre is exported and recently has been sent to interior points like Cuenca where the hat industry is growing.

The export of crude rubber in 1926 amounted to

lb., valued at $592,447. It is gathered mainly from forest trees.Gold and silver are almost entirely from the Zaruma mines, in El Oro province. The ore comes from quartz veins in andesitic rocks. In 1926, 62,486 oz. of gold were produced and 92,400 oz. of silver. In 1927 the production amounted to 64,240 oz. of gold and 87,600 oz. of silver. A very small amount of gold is produced in Ecuador from handwashing operations practiced by the Indians. No other metals or minerals are produced with the exception of petroleum. Salt, however, a Government monopoly, is obtained from sea water, near Salinas on the Santa Elena peninsula, west ern Ecuador.

Petroleum and its products rank seventh. The only producing area is situated on the Santa Elena peninsula on the Pacific coast. The production of petroleum which amounted to 57,00o bbl. of 42 gal. to the barrel in 1917, attained in 1926 about 350,0oo bbl. of which the Anglo-Ecuadorian Oilfields Ltd. is reported to have produced 292,866 bbl., and to have refined and marketed locally one-third of this amount, the remainder being exported. The con sumption of local petroleum products in 1926 amounted to 309,808 gal. of gasolene, 24,322 of gas oil and 438,685 of kerosene. In addition there were imported 529,290 gal. of gasoline, 5,627 of gas oil and 341,500 of kerosene. There are four petroleum refineries with a total crude oil capacity of 187 bbl. per day. In 1926 both the South American Gulf Oil Co. and the Standard Oil Co. of California suspended operations in Ecuador. The exports of tex tiles rank next in importance to petroleum. There were exported in 1926 321,131 lb. of textiles (cotton, hemp and wool) valued at about $258,115. In 1926 the export of fresh fruits reached a value of $235,202. Following these in importance are cattle hides which in 1926 amounted in value to about The 1926 crop of rice was below the average. Statistics of pro duction do not exist but the crop is estimated at between 4o and 5o million pounds, of which 1,693,685 lb. valued at $77,403 was exported. The export of kapok (silk cotton tree fibre, Bombax ceiba) was valued at $53,631. The cotton crop for the period July 1, 1925 to June 30, 1926 was a small one and estimated at about 3,50o bales of 400 lb. each. There were lb. exported at a value of $53,338. The output of sugar in Ecuador is small and has i4th place among its exports. Much of the sugar cane is turned into rum which is locally consumed. The manufacture of shoes has so developed that in 1926 the value of this export amounted to $39,955• Excellent butter, which is manufactured in the highlands, is there placed in sealed tins and exported. In 1926, 172,865 lb. of butter were exported, valued at about The export of live animals (cattle) attained the value in 1926 of about $30,291. Among other exports in order of importance are the fibre of the Mocora palm, cinchona bark, bamboo, cereals, potatoes, balsa logs and matches.

Archaeology and Antiquities.—All we know about human life in Ecuador up to within a few years before the arrival of the Incas, i.e., about two or three generations before the arrival of the Spaniards in 1527 is contained in archaeological and linguistic remains, for writing of any kind was not only unknown to the earliest inhabitants but even to the Incas themselves.

At various places in the western lowlands, in the central high lands and even in the forests east of the Andes are found archae ological remains, which prove the existence at certain times of a considerable culture. Although objects have been found which according to Uhle point to a relationship with the Maya civiliza tion in Central America, which was flourishing as early as A.D. 68 and probably much earlier, other objects indicate the presence of man in Ecuador several thousand years ago.

The pre-Inca archaeological remains of Ecuador are of three non-related types of culture. One, peculiar to the high Andean valleys, a second, to the Pacific coast lowlands, and a third, to the forested region east of the Andes. The first two types prove, says Uhle, that two, perhaps independent, migrations from Central America took place, and that the emigrants were profoundly in fluenced afterward by a widely different environment. The region east of the Andes has furnished little archaeological material, but this shows a close affiliation with objects found in the great forest area along the upper Amazon, whose inhabitants Uhle be lieves migrated from Central America, but turned eastward from the isthmus of Panama to follow the north coast through Colombia, Venezuela and the Guianas to the mouth of the Ama zon, which it ascended. Perhaps at the same time there was a contemporaneous filtration of people south by way of the numer ous waterways which drain into the Caribbean sea. The first type of remains, i.e., those peculiar to the high Andean valleys of Ecuador, may be subdivided into three minor classes in each of which the remains show a more or less centralized development. Remains of the first subdivision are found in the three northern provinces, Carchi, Imbabura and Pichincha. Those of the second class come from the region near the volcanoes. Tungurahua and Chimborazo, and those of the third subdivision from the provinces of Canar, Azuay and Loja in southern Ecuador.

The most noteworthy features of the ceramic art of the first subdivision are long slender vessels found in large numbers in the deep, well-like tombs at Angel and vicinity, and bowls painted with many motifs of great interest in aboriginal decoration. The second subdivision is characterized by vessels with thin walls, or namented with straight or wavy parallel lines. This is the most important of all the ancient culture centres of the Andes because of the stratified sequence revealed in excavations, where six hori zons have been recognized, according to Uhle. The lowest of these, which is called the Proto-Panzaleo, no. z, shows profound Central American influence, as Uhle has declared. The Proto-Panzaleo, no. 2, which overlies the first, is a continuation of the first but with marked traces of a new influence from the north. The Tuncahuan overlying this is thinner and therefore indicates a period of shorter duration than the others, but it is more wide spread, being found over almost the entire Andean region of Ecuador. It is marked by the disappearance of tripod vessels, by abundance of negative painting, and by the first white pottery ornamentation. Here also appear objects of copper. The next, or San Sebastian layer, contains new types of pottery vessels, and here progress was made in architecture, as shown by the ruins near Guano. In the fifth horizon from the bottom the art of Chimborazo reached its highest development. Negative and positive painting of earthenware flourished, and jars with con ventional human faces and arms, placed in low relief on the necks and upper body parts of the vessels are characteristic. In this restricted region there is much pottery of this style, but none has been discovered beyond. Human bones and innumerable small shell beads have been found in some vessels, while in others yel low powder reveals Chicha sediment showing that they had been filled with liquid for the refreshment of the deceased with whom the receptacles had been buried. Many copper ornaments are in this horizon. This is the art of the Puruha who lived as late as the time of the Spanish conquest. The sixth horizon, i.e., the most re cent, is called the Huavalac and is characterized by lost colour ware.

Near Canar, Azuay and Loja, a high degree of culture is revealed of marked Central American influence, says Uhle. Here archi tecture reached a high plane as the ruins of splendid fortresses and other edifices attest. A wealth of gold ornaments and implements has been found in tombs at Chordeleg and Sigsig. In the second great cultural area, viz., that of the Pacific coast, climatic condi tions were very different from those in the highlands, for the region is comparatively low and almost entirely covered with for ests. This zone contains two cultural centres, one extending from what is now Esmeraldas south 15o m., and the other in the prov ince of Manabi with its alternate arid and humid climatic condi tions. These two cultures, says Saville, prove the existence of two distinct peoples whose occupancy extended over a considerable period, and whose highest development seemingly was reached long before the coming of the Spaniards. Their cultures differ widely from those represented by the artefacts of the highlands, and apparently there was no connection between the two.

In some respects the most interesting culture in Ecuador is that of Esmeraldas. Prominent features are the surprising advance ment it shows in modelling clay figures and the great progress in gold working. A dominant feature is the almost microscopic char acter of many of the objects fashioned in filigree; another is the occurrence of jewels of pure platinum or of platinum and gold filigree. Many pieces are so closely allied to Mayan artefacts as to be almost indistinguishable. The type of culture in general is intermediate between the Mayan and that of the Peruvian coast.

Of the Manabi culture, the outstanding feature is the develop ment of stone architecture, almost entirely unknown in the in terior highlands and entirely on the Esmeraldas coast. The Manabi sculptures are unique in South America, says Saville, and have been found in the ruins of houses in hilltop villages and in a few town sites on the arid plains of Manabi. These sculptures in clude stone seats, believed to have been used ceremonially in household sanctuaries, sculptured slabs of stone, or bas-reliefs, representing female deities, etc., columns recalling those of Costa Rica, birds, animals and human figures in stone. A few pieces of copper and some ornaments of gilded copper are the only examples that have been discovered thus far of the metal work of the an cients of Manabi. In their towns the dead were buried in bottle shaped tombs cut into the solid rock as well as in mounds or "tolas." The third great zone of culture east of the Andes, has not been studied. It is represented by a few remains in the Napo region which distinguish it from that of the neighbouring highlands and the Pacific coast ; it is apparently related to one farther east near the mouth of the Amazon.

Writing was unknown before the Spanish conquest. At the time of the arrival of the Incas in Ecuador, a number of languages were spoken. Several of these survived the super-position of the Inca language, i.e., the Quechua, to the time of the arrival of the Spaniards. One, the Esmeraldas, has only died out in recent years, while two, the Cayapa-Colorados, and the Jibaro still survive owing to their existence in inaccessible regions. On the basis of geographic names as well as the vocabularies of the three known pre-Inca languages above mentioned, the following languages are recognized as having been in existence at or shortly before the arrival of the Incas: Quillacingas, Pastos, Caranquis (or Imbaburas or Cayapa-Colorados), Tacungas or Panzaleos, Puruhaes, Canaris, Paltas and Malacatos or Jibaros, Bolona (Rabona and others), Esmeraldas, Manabitas or Mantenos, Mochica (or Yunga), Aymara and Quechua.

Senor Jijon y Caamano thinks that the oldest types represented in Ecuador were the Cayapa-Colorados, the Jibaros and the Chimus and that the others represent modern elements in Ecua dorian ethnology. For Inca history see INCAS.

Spaniards' Arrival.

In 1526 Bartolome Ruiz, the pilot of Francisco Pizarro, having been sent south from the main base of the second expedition for the conquest of Peru, at that time situated at the mouth of the San Juan in what is now Colombia, rounded Cape Pasado to i ° S. and returned. He was thus the first European to cross the Equator on the Pacific coast of South America, and to see the shores of what is now Ecuador. Ruiz first reached the Esmeraldas where the present town of Esmeral das is situated and discovered there three large settlements of Indians who received him in a very friendly manner. They wore jewels of gold and three of the Indians who came out in canoes to receive Ruiz, wore golden diadems on their heads.Ruiz on his return to the San Juan informed Pizarro of his discoveries, and then, joined by Pizarro and Almagro, made a second voyage as far south as Atacames, discovering more large towns, much cultivated ground and a formidable array of well armed Indians. Returning to the island of Gallo, in i° 57' N., they sought reinforcements. Early in 1527 Pizarro sailed to the gulf of Guayaquil opposite the town of Tumbez where they saw the undoubted signs of a great civilization, confirmed by a cruise as far south as Santa (9° S.). Pizarro returned to Spain where, by the contract between himself and the Crown, dated July 26, 1529, he was appointed captain general and "adelantado" of the region. He returned, this time with a large retinue, among them his four brothers, his young cousin Pedro Pizarro, the future historian, and several Dominican priests. He sailed from Panama on Dec. 28, 1531, with three small vessels carrying 183 men and 37 horses, and in 13 days arrived at the bay of San Mateo, in northern Ecuador, where he landed his forces and commenced a devastating march along the entire western coast to the gulf of Guayaquil. He crossed this in boats to Puna, where a destructive war was waged with the unfortunate natives. After subjugating them Pizarro crossed over in ships to the mainland where now is situated the town of Tumbez. Pizarro and his forces left Tumbez on May 18, 1532, founded the city of San Miguel, marched on ward in search of the Inca Atahuallpa, made him prisoner and massacred his forces. Atahuallpa was executed in the square of Caxamarca on Aug. and the Inca empire came to an end.

Pizarro, desirous of forbidding the entrance of adventurers into Peru to make discoveries on their own account, sent Sebastian de Benalcazar as his representative to govern San Miguel which was at that time the key to Peru. In Nov. 1533, Benalcazar learned that Pedro de Alvarado, one of the conquerors of Mexico, had sailed from Guatemala to take the kingdom of Quito, which was famous for the riches of Atahuallpa. Benalcazar collected a few Spaniards and Indians, marched from San Miguel in the last days of 1533 and crossed the cordillera of the Andes to the great high way of the Incas in the province of Loja, now Ecuador, at that time inhabited by peaceful tribes of Palcas. Following this north without opposition, he reached the pueblo of Tomebamba in the country of the Canaris and persuaded these tribes to join forces with him against their enemies to the north. He then marched north through the "province" of Azuay, defeated the Indians at Riobamba and finally in May or June 1534 arrived at the "city of Quito" which he found in ruins. He then continued north to Cayambe where he received word that Almagro had been sent by Pizarro to join forces with him in opposing the expedition of Pedro de Alvarado which had landed at Puerto Viejo March 1534 and which was proceeding with frightful hardships straight east from the coast through unknown forests to ascend the west slope of the Andes where no trails even existed. Returning to Riobamba, Benalcazar met Almagro and they founded the "city of Santiago de Quito" on Aug. 15, as an evidence of formal possession of the territory by Pizarro. This then was the first "city" to be founded in Ecuador. Alvarado when he finally reached the summit of the Andes, after one of the most extraordinary expeditions of the Spanish conquest, found that he had been outmatched. On Aug. 26, Alvarado agreed to retire from Peru.

Pizarro then proceeded to pacify Ecuador. The city of Santiago de Quito, founded near the present site of Riobamba, was moved to the present site of Quito, on Aug. 28, 1534 and the name changed to San Francisco de Quito. The territory embracing the most northern limits of the Inca empire was soon conquered and finally the conquest continued north into what is now Colombia. It was then continued east of the Andes. Lured by the account of fabulous riches, Francisco Pizarro appointed his brother Gonzalo, Governor of Quito on Dec. 1, 154o, and the final conquest of Ecuador took place. Leaving Quito in Feb. 1541, Gonzalo Pizarro crossed the Guamani pass of the Andes, 13,35o ft. above the sea, wandered in the forests east of the Andes many months and finally, after a feat of exploration which brought him to the Amazon and permitted Orellana, one of his lieutenants, to descend it to its mouth, returned to Quito in rags and almost alone, leaving his companions in unmarked graves in the forests east of the Andes.

Conquerors' Discords.-The