Egyptian Costume

EGYPTIAN COSTUME Until the i8th Dynasty men in the way of costume wore a sim ple white kilt, which under the 12th Dynasty was often made very high, so that it began almost immediately under the armpits. It was often starched and stiff in the case of persons of some rank. Kings wore more particoloured garments, of the same general type ; in archaic days unconventional clothes were apparently worn by them, which later fell out of use. In early days the natural hair was worn long, and the kings kept it in a linen bag of characteristic shape, to exclude the dust, with a pigtail behind, which in later times was retained as a specifically royal head dress, pigtail and all, although the head was really shaved and a short wig worn. Wigs were probably introduced very early, and it may well be imagined that the discomfort of thick and long hair in the Egyptian climate conduced to their invention. We certainly find them in use as early as the Old Kingdom, and a fringe of false hair was found in a Ist Dynasty tomb at Abydos. Under the 4th and 5th Dynasties a short wig of curls cut step-wise was popular ; wigless heads are rare. Under the II th, we have at the British museum two companion figures of a noble wearing each a different type of kilt, and one a short wig, the other a skullcap. Under the I 2th Dynasty the hair was kept shorn close to the skull rather than shaved, and the wig was of a longer and very conventional type ; men are often represented without it. Under the 13th Dynasty the wig grows longer still, and either it (or possibly the natural hair?) is dressed in three masses, one over each shoulder, the third down the back, something like contem porary female fashion (see below), but not plaited.

Under the 18th Dynasty the long natural hair was commonly worn again, sometimes simply parted in the middle and combed down over the shoulders, but far more usually surmounted by a short wig, so that we see the natural hair falling in front of the ears to the level of the chin or shoulder, while the short artificial wig above it is cut off diagonally across the ears, and forms a square fringe of curls in front. Many men however undoubtedly shaved the head, as of old, and wore nothing but a wig, usually imitating the combed wig and long hair fashion, the locks being stiff curls as artificial as the rest. In the Ramesside period all men of position appear to have shaved the head and to have worn wigs of this type; priests now usually wear no wig. This fashion now became sal. Under the Bubastites the "step" form, which had continued sporadically since the time of the Old Kingdom, came in again generally. Under the Saites at first a modification of the side wig, later a full rounded form was usual besides the archaistic "step" form. Under the Ptolemies and Romans Egyptian men seem to have generally pensed with wigs, appearing always with carefully shaven crowns. Boys at all times preserved the ancient juvenile fashion of ing only part of the head, generally the left side, and wearing a single thick plait of their own hair over the right ear, hanging below the shoulder; wigs were an attribute of manhood. Royal princes of mature age wore an imitation of this lock to indicate their filial relationship to the king; and a particular rank of priest wore it combined with a short wig over the rest of the scalp, through a hole in which the plait emerged, as a religious vestment. Caps, or hats, except occasionally a light skull-cap, were not worn till Roman days. Peasants habitually wore their natural hair more or less long, and usually worked naked or with but a close-fitting waist clout, as they do to-day. Under the i8th Dynasty men's dress became more elaborate (see ART) ; over the waist clout or kilt a long linen robe was worn, carefully fluted or gauffred, depending from just below the navel, while a cape or semi-sleeved jacket of similar material covered the shoulders.

Necklaces were worn more commonly than before, and such things as bangles, while ear-rings or ear-studs were now in troduced from Asia and were worn of to the middle of the dynasty as ordinarily by men as by women. The studs (of rosette shape) were large and made a great hole in the lobe, which is always indicated in the statuary of this time, and found on the mummies. Later on, after the loth Dynasty, these great ear-studs were no longer worn by men, and after the 22nd women also seem to have given them up. But small ear-rings were certainly worn by men as well as by women under the Saites, though the piercing of the lobe necessary for them was not noticeable enough to be represented in the statues. Shoes, or sandals of reed or palm-fibre were now usual for the better classes ; earlier the feet had always been bare.

The elaborate dress of the r8th Dynasty persisted with little alteration till Ptolemaic times, although under the Saites men are often represented archaistically as wearing only the kilt, as under the Old Kingdom. In Roman times a new fashioned gar ment with dagged borders leaving one shoulder bare, was intro duced. The royal crown proper , which remained the same from the 1st Dynasty till Roman times, was composed of two parts, the upper, white, for Upper Egypt, and V , red, for Lower Egypt. A peculiar blue royal helm, ( was introduced under the 18th Dynasty.

Women.—The early dress of women was a close-fitting gar ment, often blue, with a yoke over the shoulders and a "hobble" skirt. Wigs were early worn over the natural hair which is shown parted in the middle beneath it in a 4th Dynasty statue in the British Museum. Except under the r 3th Dynasty, when the men's coiffure was as long as that of the women, the women's wigs were always longer than the men's. Under the r 2th the hair, real or false, was worn in a peculiar style, in two masses, bound with gold, and turned up and out wards at the ends on the breasts.

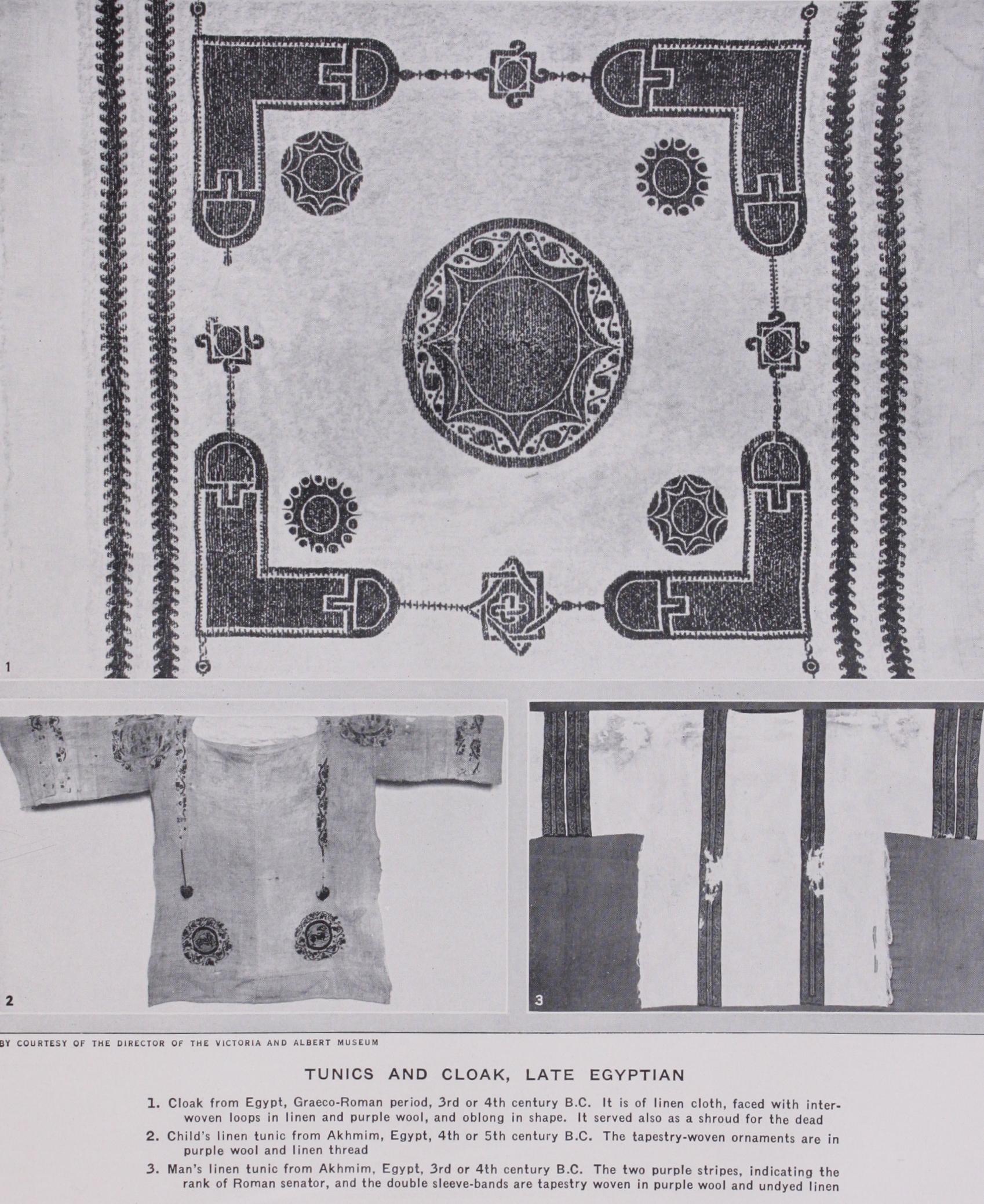

These masses were mostly of small plaits. This coiffure con tinued till the r8th Dynasty, when it was succeeded by a more flowing coiffure of plaits and curls. Certainly women some times had shaven heads beneath their wigs like the men, but the natural hair was no doubt com monly worn long by them, whereas it never was by the men after the pre-dynastic period except possibly under the r3th and certainly under the r8th Dynasty. Towards the end of the r8th Dynasty fashionable women took to exposing their shaven polls, which they never had done before, dropping the use of the wig altogether. Queen Nefertiti wore a high cap or polos on her shaven crown, with in f ulae or ribbons hanging from it behind, but her daughters are represented with shaven, and what is more, deformed skulls; it is evident that the practice of elongating the female skull in childhood rather on the style of the Botocuds Indian or Brazil, the Incas or the Solomon Islanders, was fashionable at the `Amarna period. This fashion seems not to have persisted for any length of time, but the royal women certainly continued to shave their heads, and go without wigs, in order to wear certain headdresses with convenience, for a long time afterwards. The female mummies of this and later time usually exhibit a mixture of real and false hair when the "hair" is not wholly a wig. But one woman, an unknown person buried in the tomb of Amenhotep II., has very long natural hair. Small girls often wore part of their natural hair plaited at the side to signify youth like the boy's sidelock, or even often had their heads partially shaved in complete imitation of the boys. The older tight dress which we see represented till the end in the case of goddesses, gave way under the r8th Dynasty to a more gracious costume of gauffred linen, on much the same lines as that of the men, but of a more flowing and robe-like character. Particoloured robes are worn by queens. Necklaces, ear-studs, sandals, etc., are the same as the men's, though the women do not wear sandals so often as the men. This general costume continued till the end, when colours came in ; in the late Roman period elaborately-patterned Gaped or shawled garments were worn. Women often seem to have worn a lily on their heads, and both sexes at festivals were fond of placing a lump of highly scented unguent on the head, which is carefully represented in the tomb paintings and stelae. In Roman times women (and men at feasts) wore large wreaths ; Greek costume was then no doubt largely worn by both sexes. Otherwise only the queens wore anything in the way of a headdress (see above). (H. R. H.) Sources of information about the dress of the ancient Greeks and Romans are to be found in their literature, their sculpture and their painted vases. Existing examples, though mostly provincial and late in origin, are also of some historical interest. In primi tive times, among both the Greeks and Romans one voluminous cloak was thought sufficient dress for a man, and even in later times it was the only garment regarded as indispensable. A tunic or shift was nevertheless worn by men, women and children. At first it appears to have been sleeveless, but individual fancy and variations due to colonization or conquest caused much diversity in apparel. Among the Romans the tunic was often ornamented. The tunica palmata was worn at triumphs. Men of senatorial rank wore a tunic with a double stripe in purple down the front (tunica laticlavia). Knights had a narrow stripe from each shoulder downwards (tunica angusticlavia). In this latter form the tunic went into common use. A man's linen tunic of Graeco-Roman times from Egypt (Pl. III., fig. 3) has the two purple stripes as well as double sleeve-bands. Other tunics found in Egypt were more richly adorned. One for a child (Pl. III., fig. 2) has in ad dition a roundel on each shoulder, and two others both on front and back. In course of time the simple slit for thrusting the head through was shaped or cut away in front. Two tunics were sometimes worn; as time passed (and probably always among the peasantry) no other garment was considered necessary.

The cloak, worn over the tunic, varied much at different times and places. Among the Greeks it usually took the form of a large oblong cloth wrapped about the body so as to envelop it from the neck to the ankles. The Romans used a similar garment, known as the gallium. But the distinctive Roman cloak was the toga, a large cloth in the form of the segment of a circle (rather less than a semi-circle) worn with the straight side uppermost. One end came forward over the left shoulder reaching nearly to the ground. The garment was then passed round the back, over (or under) the right arm, and across the front, the other end being thrown over the left shoulder to fall behind. There were variations in manner of wearing and in shape according to time and place. The toga was laid aside when there was work to be done. In later times it became a ceremonial garment, gradually losing its amplitude until it was no more than an ornamental band worn over the shoulder by certain officials. A few shreds of men's and women's garments, too incomplete to betray their form, have been excavated at various times during the past 8o years from Greek graves of the 3rd to the 5th century B.C. in the Crimea. They are chiefly of wool, though linen, too, has been found (see TEXTILES). Though it appears that the Greeks and Romans both favoured undyed wool for their garments, these specimens from the Crimea are mostly coloured (generally purple or green). Some are plain or striped; others have woven, embroidered or painted designs. The ornamentation includes deities, figures on horseback, chariots, birds, vines, honeysuckle and scrolls.

In Graeco-Roman Egypt the cloak is oblong, and often of ample dimensions. It is variously ornamented, with figures, animals, birds, fishes, trees, plants, foliage and conventional patterns. A remarkably fine example, of linen, with purple ornamentation in looped weaving, is here illustrated (Plate fig. 3) . The Roman cloak was put to a variety of uses. It might be spread over a bed or couch or laid on the floor. It served also as a shroud for burial. Those found in Egypt have all been used at last for en veloping the dead. The tunic and cloak were the chief garments of Greek and Roman times, but various others were worn in dif ferent places and on particular occasions. One among them, the chlamys, may be mentioned. It was a kind of short mantle or scarf, apparently more ornamented (as a rule) than the large cloak. In shape it seems to have been either a narrow oblong or the segment of a circle. The garments of the Greek and Roman women were more voluminous than the men's, but otherwise they did not differ greatly in classical times. Instead of the toga, women wore the stola, with the gallium over it. Men often went barefooted, but leather or wood sandals and buskins were worn. Women wore shoes, and carried fans and parasols. Knitted socks, and knitted or netted caps, hair-nets and bags have been found in abundance in Egypt. Caps of fur and leather, and broad-brimmed hats, were worn on occasion. Brooches, clasps and girdles were used, especially by the women, but the skill of the wearer in adjusting the cloak seems to have been chiefly relied on for keep ing it in position.

The tunic and cloak, which were the principal garments worn in Greek and Roman times, continued to hold their place, with modi fications, for many centuries. As the tunic became the chief gar ment, it was sometimes elaborately decorated. One early Christian writer speaks of people wearing garments on which animals, for ests, mountains or huntsmen were figured, while on others were biblical scenes. Late pagan and early Christian garments, found in Egypt, have ornamentation of this nature.

Mediaeval.—At the time of the Norman conquest of England the dress of men and women consisted of a couple of tunics and a loose cloak. The chief innovation was the tight "chausses" or hose enveloping the legs; in classical antiquity trousers were a barbarian garb. From the two tunics were evolved the jackets, pourpoints, jupons, jerkins and doublets of later times, and from the short cloaks the various over-garments, of ten taking fanciful shapes in the middle ages. Patterned materials were often used, though apparently not quite so much as they were afterwards. It is probable that the initials and devices personal to the wearer, seen in the i 4.th and i 5th centuries, were for the most part of embroidery. They might occur once on the sleeve or shoulder, or they would be powdered over the whole garment. The large painted portrait of Richard II. of England in the sanctuary at Westminster Abbey shows his robe powdered with crowned R's, and presumably the letters sometimes to be seen on the dresses of unidentified individuals in paintings and tapestries had a per sonal significance. Another portrait of this king, on the celebrated diptych in the possession of the earls of Pembroke at Wilton, shows his mantle covered with crouching harts. The white hart was his personal badge, and again it explains other instances of such devices, though it should be remembered that fanciful repre sentations of this kind formed part of the general repertory of the pattern-designer in mediaeval times. By the middle of the i 5th century, rich velvets, with variations of the lobed "Gothic" pat tern, often inwrought with gold thread, were much used for costume among the well-to-do.

Only a summary statement of the changes which dress went through during the middle ages and later times can be given here. The following outline has more particular reference to England, but generally speaking it holds good for western Europe, and (where applicable) to America. Some developments might occur earlier in France or Italy, where many fashions originated, and they would tend to survive later in the north.

What may be described as "tailoring," as distinct from drap ing, comes into notice about the end of the i3th century. Gar ments then begin to be shaped more to the body, leaving less liberty of adjustment to the wearer. In the latter part of the r 4th century "dagging" (the cutting of the edges of the garments into fanciful shapes) takes an exaggerated form, which it keeps for half a century or more.

For head-coverings the plain white wimple began to give way, towards the end of the 14th century, to elaborate head-dresses— the horned, the mitre, the turban—culminating in the fantastic steeple head-dress or "hennin" of the later i5th century, from France. In the 14th century men wore a kind of hood turned sideways on the head. This was followed by a closefitting cap which, towards the third quarter of the r sth century, was height ened so as to resemble the Turkish "fez" of ter which it became lower and flatter.

Shoes, which in early times were for the most part of fur or leather, tied by thongs round the instep or ankles, gradually took form with sole and uppers approximately more or less to the shape of the foot, until in the r4th century a tendency to bring the toes to a sharp point is noticeable. In the later years of this century the uppers were sometimes pierced in fanciful shapes. Chaucer refers to this practice when he speaks of the priest Ab salon having "Paul's windows carven on the shoes." Shoes with Gothic tracery over the instep were shown in the wall paintings representing King Edward III. and members of his family, for merly in St. Stephen's chapel at Westminster. At the end of the century the shoes of Richard II. are covered with quatrefoils and discs. The "Cracowe" or "poulaine," from Poland, with pointed toes of greatly exaggerated length, then followed, until at the end of the isth century the fashion ran to the opposite extreme.

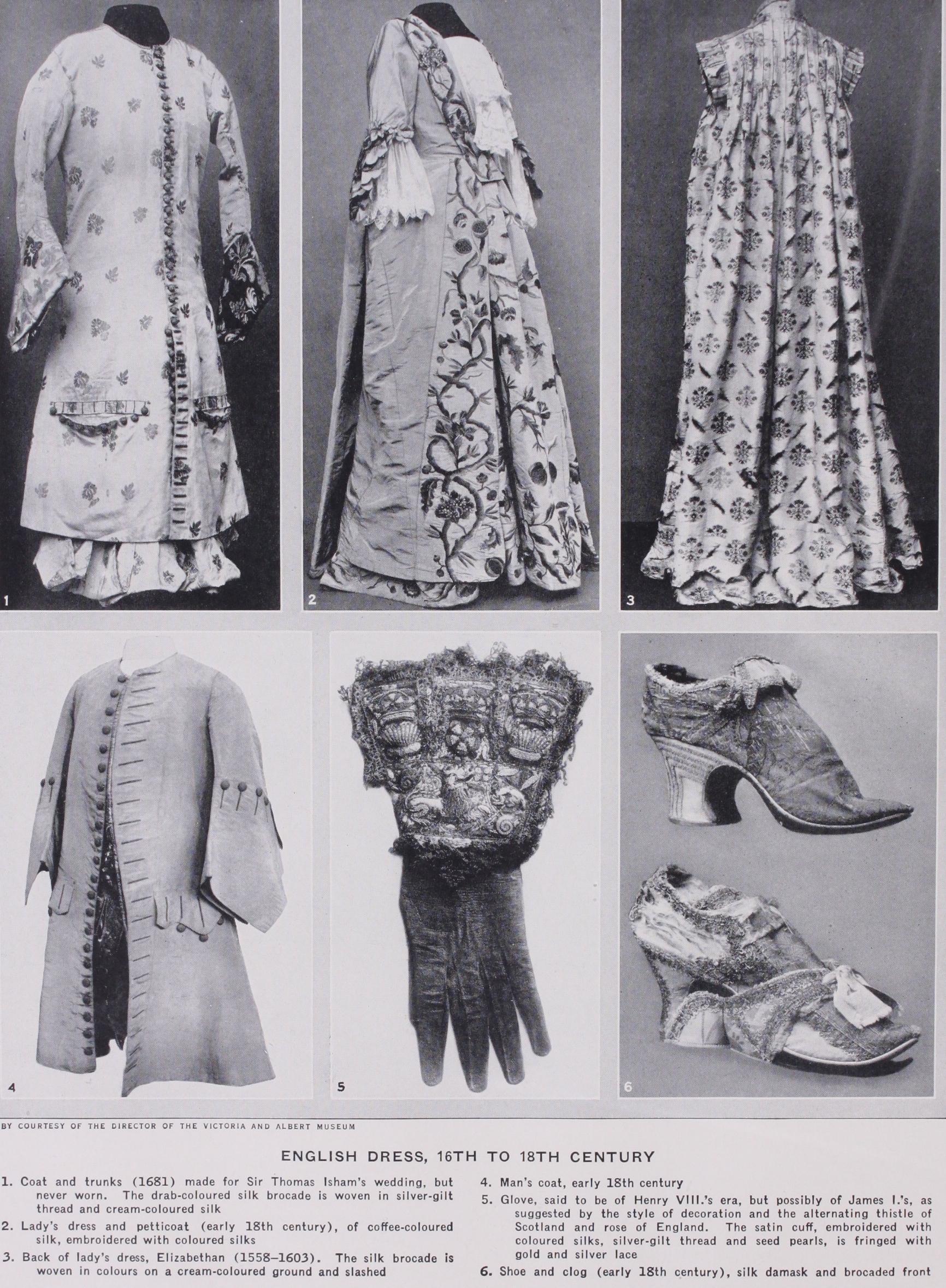

16th and 17th Centuries.-In

the first half of the i6th cen tury took place the meeting of the French and English kings at the "Field of the Cloth of Gold." This phrase only reflects general tendencies of the time, when fashionable men's clothes were loaded with jewels, and they are said to have spent their fortunes upon their clothes. Early in the i6th century the hose were divided into stockings (bas-de-chausses) and trunk-hose (haut de-chausses). The trunk-hose went through various phases, looser or tighter, shorter or longer, following caprice rather than any progressive evolution.The slitting of men's sleeves at the elbow or shoulder, to display the garment underneath, was not unusual in the i sth century, but "slashing" in small parallel cuts is a feature of the next century. By the time of Charles I. the slashes became long slits, sometimes extending for practically the whole length of the sleeves, before disappearing altogether. In the latter half of the i6th century men's garments began to be "bombasted" with cotton-wool, hair or sawdust. They form a contrast to the dress of Van Dyck's sitters a few years later. The air of elegant refinement, which must have been due in some degree to the dress itself, is so notice able in this artist's portraits, that far on in the following century painters would endeavour to recapture some of this glamour by representing their sitters in similar garb. Women's farthingales, in the latter half of the i6th century, extended their skirts to very ample size. The euphuism of the time is reflected in dress, and exaggerated conceits form the subject of embroidery. In a por trait of Queen Elizabeth in the possession of the marquis of Salisbury at Hatfield house, her cloak is embroidered all over with human eyes and ears which, with a serpent on the sleeve, betokened the vigilance and wisdom of the wearer. A more re strained type of ornamentation, chiefly used for linen garments, such as tunics and men's and women's caps, was done entirely in black silk thread. Hence it gained the name of blackwork. It is said to have been brought to England by Catherine of Aragon. Naturalistic flowers were a favourite motive, but badges, rebuses, book-illustrations of enigmatic import, and all kinds of fanciful conceits were also included. As time went on, richness was added by the use of heavy gold thread for stems and other details, and later in the century bright colours replaced the black.

In this form, chiefly for floral patterns, it survived well into the 17th century.

The development of the frill at the neck into the great starched and pleated ruff, with its supporting standard, is a noticeable feature of the time. Completely encircling the neck at first, towards the end of the r6th century it was sometimes worn open in front. Soon afterwards it was replaced by the falling collar, but the encircling ruff and the open ruff were still worn well into the 17th century, as so many Dutch portraits bear witness.

Brims are added to men's caps early in the i6th century, and modifications rapidly succeed one another. In the second half of the century men and women wore higher and stiffer head dresses. The 17 th century brings in the "steeple" hat, and then the leather hat with broad brim and feathers. The broad-toed shoe with parallel slits or slashes is followed by a shoe in which the tilting at the heel begins. A solid corked sole comes first, then a space is cut through under the instep, to be followed by a separate heel-piece. Children's portraits show that it was cus tomary to dress boys and girls, even those of a tender age, very much in imitation of their elders.

About 166o an important change took place in men's garments, when coat and vest were first evolved as distinct garments in France. This fashion was carried to England by Charles II. At first the vest was long, reaching to the knees and sleeved. The coat was slightly longer. The coat and waistcoat of the present day are directly descended from these garments. Men's dress of about 168o is exemplified by the suit of brocade shown in Plate IV., fig. r.

The trunk-hose are full, though very soon after they might have been worn narrower, anticipating the buckled knee-breeches of the 18th century. About this time, instead of the natural hair falling to the shoulders, men took to wearing the large periwigs so characteristic of the portraits of Louis XIV. and his contem poraries ; at the end of the century they tower over the brow, giving added height to the wearer. Cravats, often of rich lace, now replace the falling collar. A notable fashion originating in France took its name from the battle of Steinkerque, fought in 1692. The French officers dressing in haste, it is said, tied their fine lace cravats about their necks. This fashion spread to other countries, both for men and women, and lasted some years.

Women's skirts were full at this time, and bodices were laced in front, sometimes with an embroidered stomacher. Hat-brims were now cocked, developing at the end of the century into the three-cornered hat.

Muffs were carried both by men and women in the 17th cen tury, and in various forms they continued in use by women well into the present century. Gloves -first became conspicuous in the 16th century, when they were often elaborately embroidered and sometimes embellished with pearls and jewels as well. In the 17th century, when the frill at the wrist gave place to the turned-back linen cuff, large gauntlets were added to the gloves, giving scope for embroidery in the style of the time. A pair of gloves was a customary gift at the New Year, and pains were taken to render them worthy of acceptance. Such gloves were usually of leather, but subsequently various lighter materials were used, and gloves might reach beyond the elbow when sleeves were short.

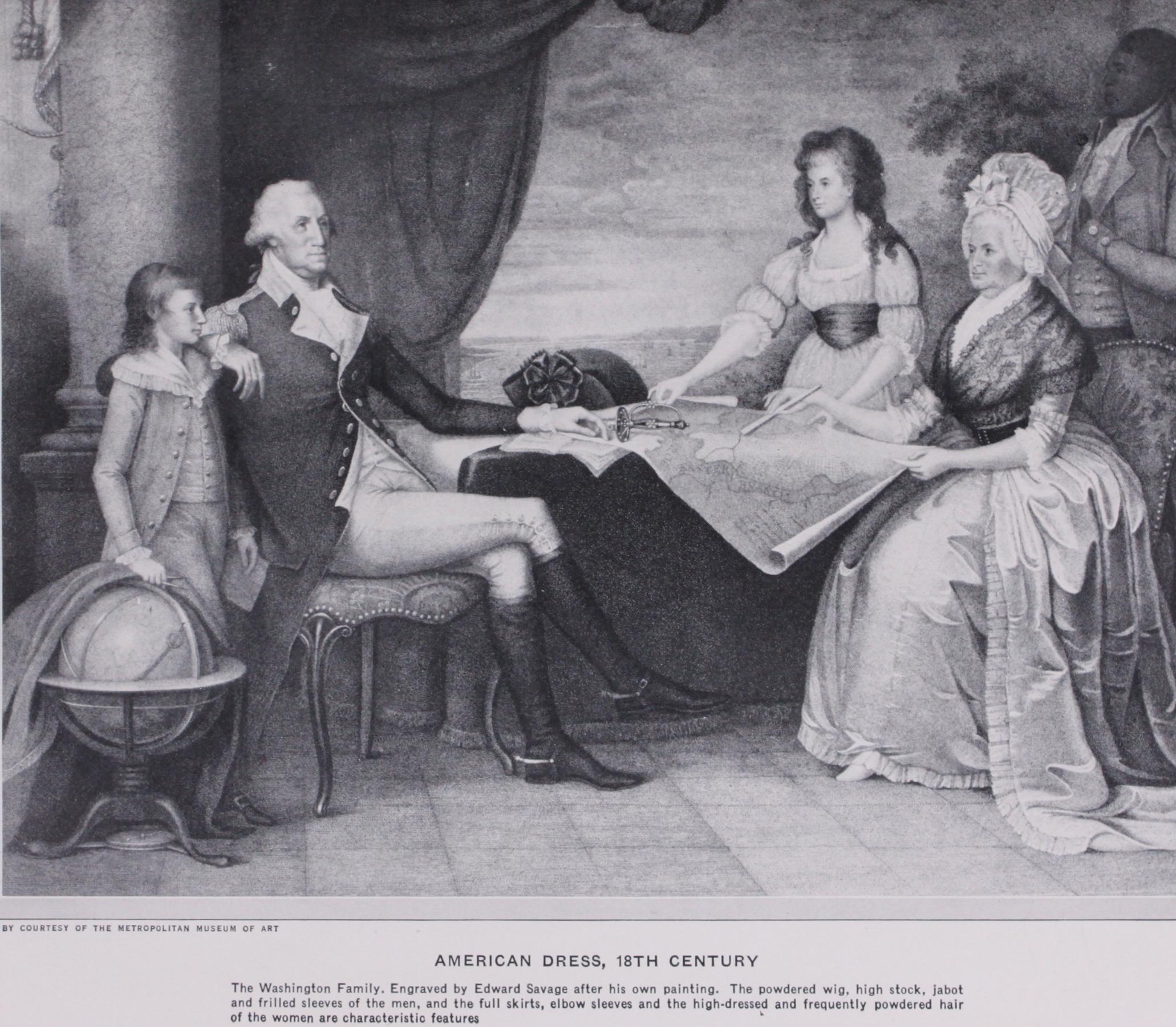

18th Century.—At the beginning of the 18th century the skirts of men's coats had become fuller and the sleeves had wide cuffs. The sleeved waistcoat was shortened, and at times it was richly embroidered. In course of time the sleeves disap pear. As the century advances a distant approximation to the frock-coat of later times is discernible, but the materials con tinue to be rich. Velvet, often woven in tiny diaper patterns, was much used. When the material was plainer, elaborate em broidery in silk, often embellished with glass pastes and spangles, was usual for fashionable dress. During the course of the cen tury, the skirts of the coat and the corners of the waistcoat were cut away in front, reducing the form more nearly to that of morning-dress of the present day.

Embroidery was used for ladies' dresses, especially for the underskirts rendered visible by the open front of the dress. The silk brocades of Lyons or Spitalfields, with floral patterns in bright colours, came into use. Indian dyed or embroidered cottons, and Chinese painted silks (Plate VI., fig. I), witnesses to the growing commerce between the maritime nations of Europe and the Far East, were made into dresses, causing much searching of heart among weavers at home, who succeeded in getting re strictive enactments put into force. Towards the middle of the century skirts became very ample, being supported by very wide hoops. The sack or sacque, a loose dress falling straight from the shoulders, continued in use during the greater part of the century. It had originated about 3o years earlier, when Pepys's wife "first put on her French gown called a sac." Later dresses, too, came from France. A letter of the year 1715 from Sarah, duchess of Marlborough to Lord Stair, ambassador at Paris, is still extant—asking him to obtain "two pair more of bodys and a night-gown" for her, and a manteau and petticoat for her grandchild. In the latter half of the 18th century women wore their hair, or wigs, dressed high above the head and powdered, and again men's wigs became larger, but they were already doomed, and Pitt's powder tax of 1795 practically put an end to them.

19th Century.—By the opening of the 19th century, the change in men's outlook had swept away much of the overloaded finery of the past and garments more supple and better suited for active life came into use. Men's coats are cut away in front in a manner resembling the modern dress-coat, the lapels are large and the collar is high and deep. Waistcoats are short and cut square. Knee-breeches are lengthened into the modern trousers. The cocked hat of the 18th century is replaced by the top-hat. The old full dress, moreover, gradually gives way to what we now call the lounge suit, used more and more for all occasions.

Women's dress at the opening of the century is marked by a graceful simplicity, with high waist and low neck. A lower waist and puffed sleeves follow. Meanwhile skirts were widening, until the "crinolines" took their most exaggerated form shortly after the middle of the century. Then followed various adapta tions of 18th century styles. About 188o the projecting "bustle" at the back was in full popularity. Fringes, trimmings, flounces and long trains were in use during the latter part of the century.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-J. R.

Planche, Cyclopaedia of Costume 0876) ; A. Bibliography.-J. R. Planche, Cyclopaedia of Costume 0876) ; A. Racinet, Costume Historique (1888) ; Victoria and Albert Museum, Old English Costumes (1915), selected from collection formed by Talbot Hughes; F. M. Kelly and R. Schwabe, Historic Costume (1925).(A. F. K.) The appearance, customs and personal characteristics of Chi nese, Japanese and Koreans are distinctly different, and this has consequently brought about dissimilarities in the dress. Only within the last few decades when European costumes have to some extent been adopted, has there been any tendency to uniformity in style.

China.—All classes in China wear a san (jacket) and koo (trousers), the combination being similar to the Western pyjamas. There are three kinds of each—the single, the lined and the wadded with cotton, to suit the season of the year. To the san is attached a narrow collar-band. The ma kua is the ordinary jacket with loose sleeves for the common people, and the baishin, a sort of vest, is worn over it. The po is a long gown and the qua a larger and longer ma kua. The po kua is the official full dress of men, while the lung po, or dragon gown, was worn by the emperor at State ceremonies. There are several other gowns in use—the Chang san in summer, chiao in spring and autumn and taminou in winter. When it is very cold the pipao, or fur coat, takes the place of the taminou. The to pang, another kind of overcoat of silk or fur, is worn by the wealthy.

There are all kinds of coats embroidered with dragons, moons, stars, hills, mountains, waters and flowers. Each design has its peculiar symbolism; frequently it is a Buddhistic emblem or the representation of some philosophical concept, such as the "waves of eternity." The mandarins were specially privileged to wear gold-embroidered clothes, and sometimes the emperor granted the nine orders of mandarins the distinction of wearing a peacock feather on the hat.

Red is a symbol for happiness, and thus we find the bride wear ing an elaborate gown of red; the tassel on the top of men's hats and the cord on their queues are red.

Japan.

In A.D. 283 two women weavers were sent from Korea to Japan to teach the making of figured silks and brocades. The ho, or ceremonial garment of the Japanese emperor and nobles, has an ancient origin ; the Chinese seamstresses came to Japan, about A.D. 30o and made this with silk imported from China. Emperor Yuryaku (A.D. 457-479) reformed the national dress and, in the reign of Emperor Suiko (A.D. 593), rank was signified by distinctive head-gear, a custom imitated from that of the Chinese Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-906). Costumes were evolved for civil ians, ecclesiastics and the militia, differing in colour, patterns, the length of sleeves and the style of hairdressing.The kasane, or loose tunic, was worn with a short lower garment called the akome. The hakama was a loose skirt reaching only a few inches below the knees over the shita-gutsu, or socks. The whole style of head-gear was called suberakashi. Kammuri, a cere monial headdress, was secured by kanjashi, or pins and the yeboshi, or cap, was worn over it.

The ladies always wear the kimono, a loose gown with a neck piece called an eri, and long sleeves, the garment being fastened by a belt. Since the Heian period (794-1159) women have in general dispensed with the hakama, and to-day the female dress for social occasions consists of an underskirt, two or three outer garments and a haori, or interlined silk coat, over the upper part. The obi, a belt about 3 yd. long and 1 o in. wide, winds about the figure.

Men in rural districts are barefooted, seldom wear zori or the wooden clogs called geta, and in the hot season they wear almost no clothing. The common-jacket and trousers of cotton crepe, blue or white in colour, a large grass hat called kaza and straw zori are the ordinary dress.

Korea.

Among the six departments of the Korean Govern ment was the board of rites, whose duty was to regulate, describe and govern the ceremonial code of polite society, including dress. Koreans dressed according to their class, and in each class distinct costumes were used by those of different ages.A chugori (jacket) and baji (trousers) are worn by all classes. The tooroomaki, a long flowing tunic, goes over these to anywhere between the knees and ankles; the higher the man's position, the more garments he wears. All these are of varying thickness to suit the weather. Women's chugori do not descend to the waist, leav ing space for a waist-band, or huridi, which is embroidered and woven by hand. (Y. K.) The evolution of modern feminine dress, corresponding closely to the emancipation of women at the beginning of the 2oth cen tury, provides one of the most captivating pages in the history of modern civilization. One often considers ridiculous the fashions of other days, but one has only to live the past over impartially to understand that all changes in fashion are rungs in a ladder leading to an inconstant ideal.

Fashions of 1900-28.

In 1900 one could not breathe freely for dust raised by skirts. Women wore frilled underclothes un known to-day. The body was imprisoned in a corset that pushed the bust forward and the lower part of the body out behind. The hair was dressed so as to follow the movement of the body. The neck was stiffened by a collar with whalebone stays. The sleeves, bodice and hat were trimmed with puffs and frills, details that at first view appeared useless but that helped to conceal the twisted line of the body. This silhouette remained without appreciable change up to 5905 when a step back to fin de siecle fashions oc curred. Sleeves were again puffed at the top, bodices were shaped to a point in front and the complicated dresses were covered with a profusion of puffs and frills. The hat was perched on the side of the head above a display of hair extravagantly curled ; it was frequently trimmed with a cluster of feathers, a mode of delicate hat-trimming that, changing place very often, lasted until 1914. In 1907 a slight Greek influence was felt in the soft materials often draped; tunics with points made heavy by tassels. The high collar made almost its last appearance. In 1909 a collar that freed the neck was popular. During the same year the short skirt ap peared for the first time in the 2oth century; a short skirt, how ever, that would have seemed very long in 1929. Enormous hats were loaded with huge, falling feathers. Already the silhouette was being slightly straightened ; the bust was less bent and the body a little less deformed by the corset.So far the few progressive changes in costume were the straight ening of the silhouette and the freeing of the neck. They prepared the way for the directoire fashions which, already having made a few timid appearances, began to reign definitively in 1910. A bloom of delicate and varied colours was obtained during this period by concealing the dress beneath a transparent tunic of a different shade. Two years later, in 1912, under the influence of a few Russian ballets, the directoire began to orientalize itself. Trouser-skirts appeared, heads were turbaned and dresses of bright colours were trimmed with gold embroidery, pearls and diamonds. This fashion, taken from the theatre, could not last long, but by its boldness it had thoroughly changed taste ; there was no more turning back to the past—the development of fash ion traced new ways. It is since 1912 that dresses have no longer hidden the elegant woman's feet and that she has matched the colour of her shoes and dress. The oriental influence transmitted by the theatre became, in 1913, dazzling. The trouser-skirt per sisted next to the skirt tightly draped round the legs; it was surmounted by a short and puffed tunic which very often took the shape of a small crinoline. One has only to compare the sil houettes of 1913 and 1900 to understand that the development of fashion was at its highest point, that the past had been forgotten. In the history of modern fashion the years 1912-14 are quite characteristic. The enormous influence of the theatre can be noticed. It attained its development about this time.

The period from 1914-20 is the least notable in the history of fashion. In 1914 the tight skirt surmounted by a wide and much longer tunic could still be seen. The following year the narrow skirt was suppressed and the tunic alone remained. From this period there is no general line of fashion; wide crinoline skirts were worn as well as tightly draped dresses with long trains. The year 1917 alone created a specific line in this period of revolution in fashion. It produced the barrel dress which was not seen the following year but which, nevertheless, for some time afterwards, left its traces in a draped movement, recalling draperies of the paniers of the 18th century. From 1914-20 there was nothing worthy of entry in the history of fashion ; the theatres giving no new styles, old styles were recalled.

The New Line.

Still novelty was sought and in 1921 the new line—the low waist was found. At the same time the skirt was lengthened slightly. The hair, drawn away from the fore head, formed a high chignon often held by a Spanish comb. The Spanish influence made itself felt, not only in combs and head dress, and for a time women draped themselves in Spanish shawls, very often using these in place of evening cloaks. In 1923 the low-waist dress was transformed into a straight dress called the tube dress, and from this was born the costume—the straight and short dress—which was generally unchanged to 1929.At its birth in 1924 it was quite simple; so much so, in deed, that it demanded equal simplicity in dressing the hair, which women began to cut like men. Dresses being simple in shape and trimming, the feminine costume tended to fall into a dreadful dull ness. Feminine elegance was saved by research in accessories and by the use of new materials. Fashion began to demand matching not only the dress, coat and hat, but scarves, gloves, shoes and handbags also; the large dressmaking firms began to make false jewels to match models, and even to make perfumes to agree with the lines and colours of their models. The seeking of harmony in the smallest details proceeded further, appearing in the make-up which in days gone by was used simply to correct faults of nature.

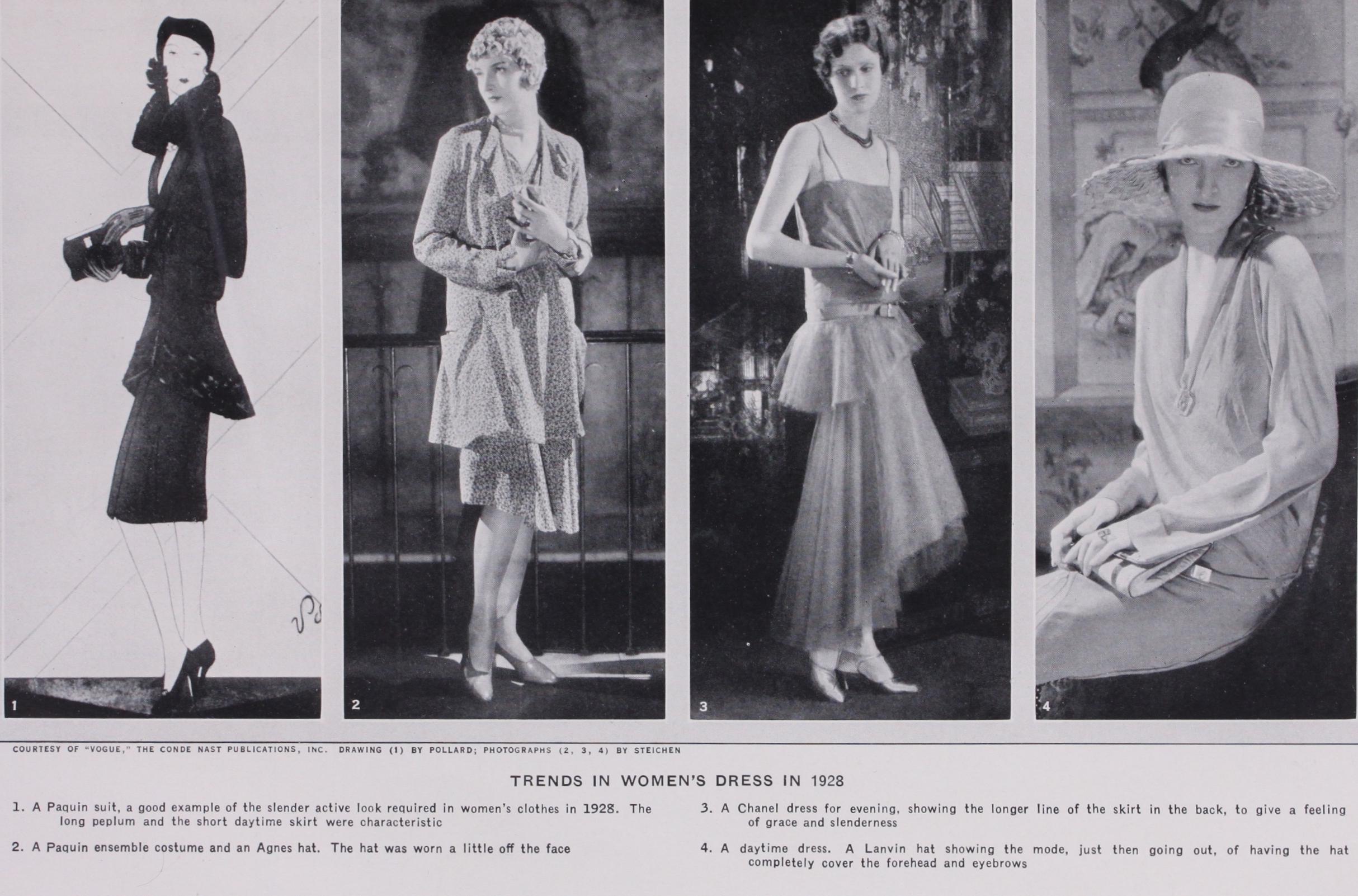

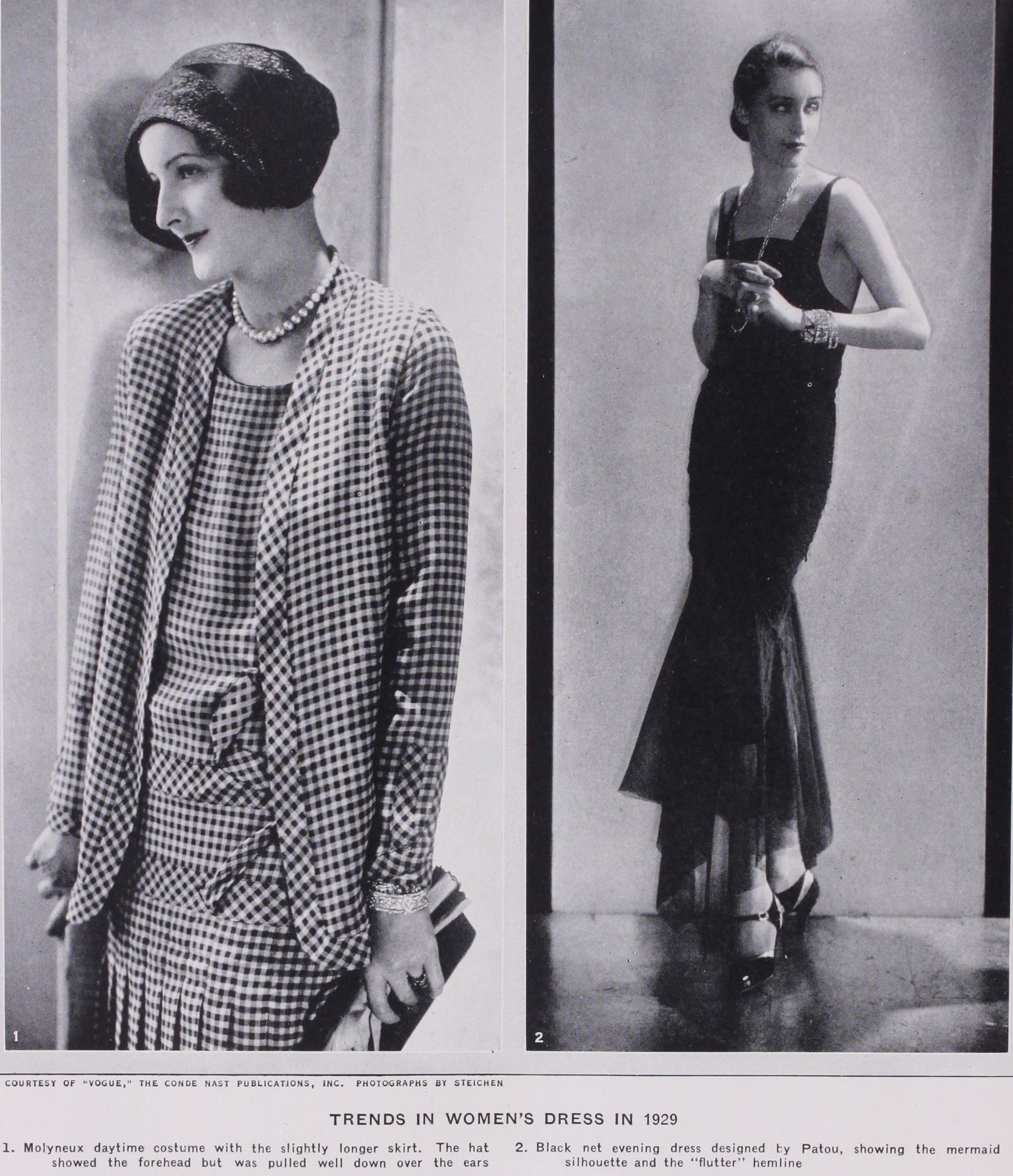

Many new materials were created in the last few years. Em broideries on plain materials gave way to printed materials ready for the making of the dress. New furs, feathers, kid, lizard and snake skins appeared on dresses. (R. DE T.-E.) Fashions from 1928 on.—With the arrival of 1928, the sil houette introduced a "flutter" to its hem line. The uniformity which had nearly reached a banal monotony during the preceding years changed during 1928 to a silhouette with a great deal of movement. The hem line began to dip in back until it almost reached the floor—particularly in evening gowns. During the day, the "sports" feeling, which had continually increased during each successive year, became even more marked. Physical exercise and intelligent diet had given the athletic figure of the modern woman a slender, active look; and rhythm had taken the place of heartiness. The hip line remained moulded—with a flat front and back—while the waist line, above, was felt rather than de fined. The longer line of the dresses in back succeeded in giving the feeling of grace and slenderness which had been very much lacking during the recent years. Hats which had completely cov ered the forehead and eyebrows were beginning to show them again. The introduction of what was known as "ensemble" be came even more important in 1928 for daytime wear.

By 1929 the hat showing the forehead had arrived. The hem line continued to remain just below the knees in front, and flow ing to the floor in back. For evening, peplums over bouffant edi tions of the silhouettes appeared—made of taffeta and faille. Day clothes remained approximately the same as the preceding year. The hard silhouette of 1925 and 1926 was completely over thrown. The subtle beginning of the higher waist line and longer skirt line was, bit by bit, insinuating itself into being. Sports clothes became longer—four inches below the knee being the popular length. Trains on evening gowns appeared, giving even greater grace to costumes—but the skirt remained short in front. Clothes were again becoming complicated—almost fussy. The uniform sort of costume of 1925 was forgotten.

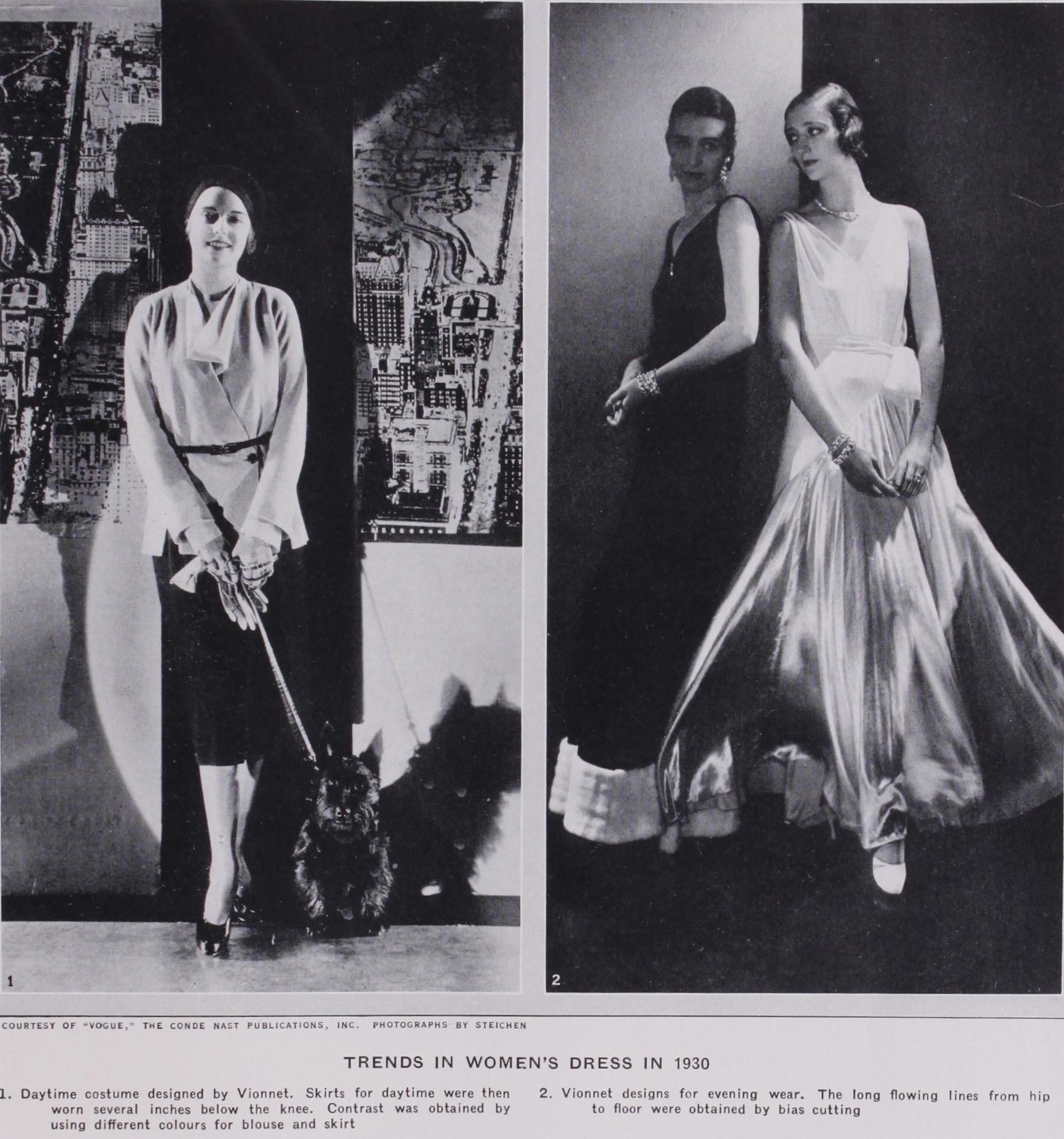

Confusion began with the introduction of the very first long skirts. Women became bewildered. They trailed these long skirts through the streets in the daytime. However, in the course of time, the novelty of the long skirt—so confusing to them at first —was gradually adjusted, and it assumed its proper place—which was for evening. The daytime skirt was worn seven or eight inches below the knee. Tea gowns and pajamas for entertaining at home were popular. A softer treatment for bobbed hair ruled. By 1930 the long-skirt had at last a sure foothold. The young so called "flapper" had become submerged. She had greeted as a new and exciting experience the feel of a long skirt swishing about her ankles—an experience which she had never felt. Her coats were fitted at the waist ; her slouch became dignified rhythm; and legs and knees were completely things of a recent past. Actually beauty of line began to appear. A Greek feeling appeared—a flowing from hip to floor for evening. Evening wraps became much longer—many of them reaching to the floor. The classical Greek line became the edict. "Brittle" lines—both for evening and day—assumed a flowing movement. These last ten months were the most confusing for both women and dressmakers in ten years. The complete and revolutionary change of after-war severity had been one of turmoil and re-adjustment.

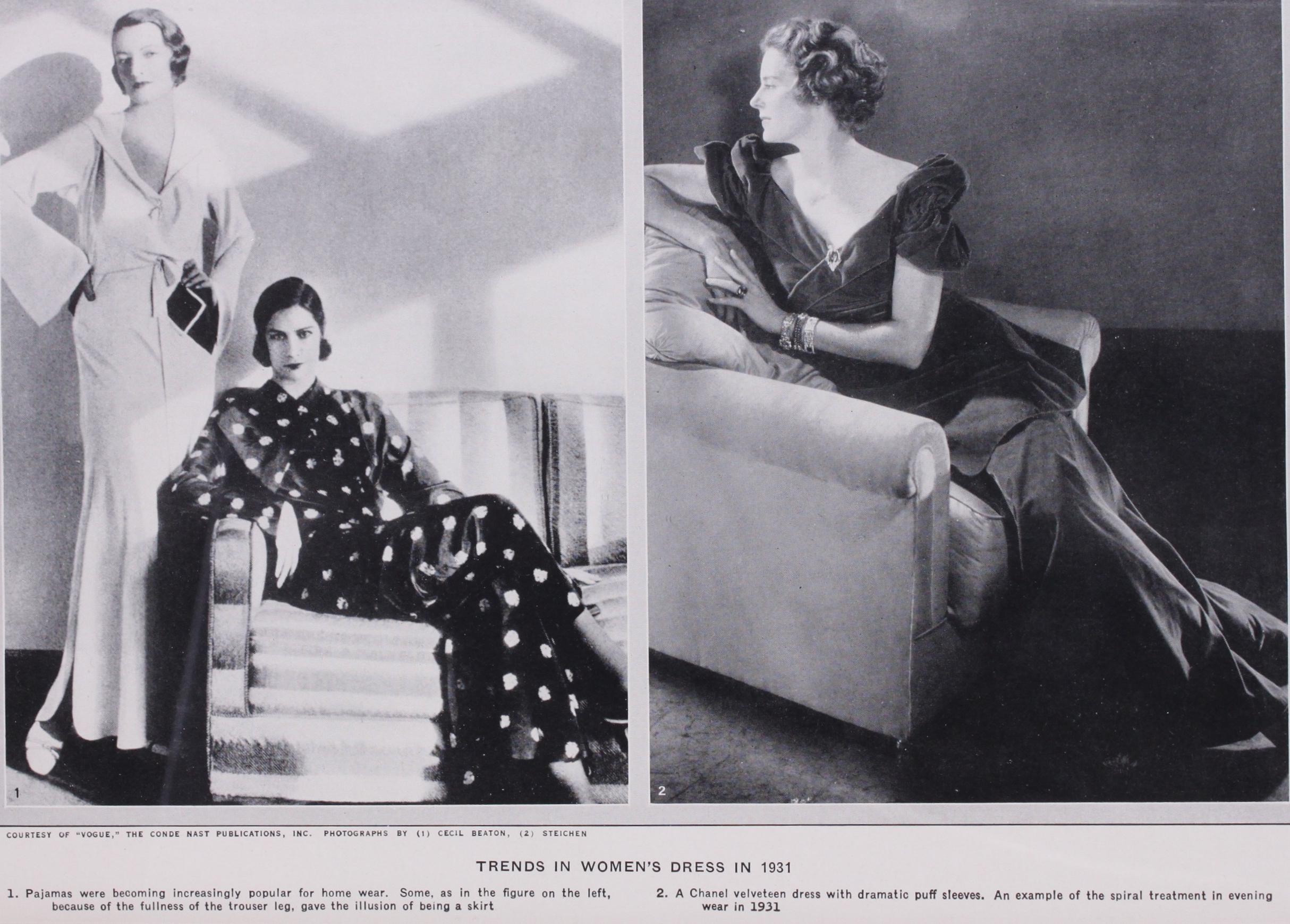

1931 ushered in a very graceful and flattering era of spiral treatments in evening dresses. These dresses clung to the figure and the women of 1931 suggested the classical figures on a Greek frieze. The pajama had become overpoweringly popular. During the summer at the watering places of the world the pajama was worn almost continuously, both for daytime and evening. Some times the evening pajama—because of the fullness of the trouser leg—gave the illusion of being a skirt. The motion picture had begun its powerful influence, and women were dramatizing their clothes far more than they ever had before. Dramatic clothes were no longer seen only on the actress. Ladies in the audience were equally exciting in their dress and frequently more so than their favourite star. Inhibitions about colour were being abolished. Gaiety, undoubtedly a reaction from the drabness of more recent years, became the exciting gesture of the day. The financial crisis had caused a rather clever pseudo bravado. It was considered chic to be poor. Wealth was changing hands. Many of the smart women of the day were financially curtailed. Fewer clothes were in once overflowing wardrobes. This seemed to give an added im pulse to inventive designers, and each month new ideas were offered. Fashion, unlike in its earlier history, changed almost fortnightly. The continual desire for something new, partly be cause of promotion in the great shops of the world, and because of the variety of ideas in the cinema and dressmaking houses, made a perpetual fireworks of ideas and variety of design during these latter years.

1932 introduced the pill-box hat, the beret, and the sporty felt. All of these had great popularity. Hats tilted over the left eye. Women remained slim and straight. The evening gown with a high neck in front, the low back, and long sleeves became ever present, even on those occasions when, several years before, only the lowest décolleté would have been correct. A casual look— a gracious look—was the keynote. Gradually a masculine note crept in. Mannish suits were worn for daytime ; sport coats were adapted from various masculine sources; and evening clothes dis played a definite masculine trend. It was the beginning of the tailored evening mode.

The year of 1933 found the straight silhouette with a mannish feeling still in great favour. High necks predominated both for evening and day. An elongated "fish tail" appeared on a great many evening gowns, giving a narrow slender look to the lady of the day. What was known as "the dinner suit" . appeared, and this tailored interpretation of a thoroughly masculinized dinner dress was worn most conspicuously by the chic woman. Jewels played a very important part with evening clothes—gold jewellery, huge and massive bracelets with a barbaric African feeling.

For daytime, hats suggested the "Cossack," or a modified form of the "fez." During the latter part of the year feathers—ostrich and other varieties—were of great importance. Trailing boas and short capes of feathers added grace and beauty to simple evening gowns. There was an ever increasing interest in shoulder treat ments. Shoulders began to play an important part in the trend of fashion. Evening gowns displayed huge ruffled puff sleeves— a mode introduced by a motion picture which became interna tional and returned to America again from Paris. Dinner hats were worn with dinner and theatre dresses. These dresses had a slender moulded look with a broad shoulder treatment.

continued to bewilder its ladies by confusing them with odd materials. Silk was woven to look like wool ; materials were made to look like glass; velvet became almost a soft fur. At tempts were made to shorten the evening gown. This was only mildly successful. A few appeared, but the evening dress re mained graceful and dignified. A Victorian feeling was introduced in necklines, and a peasant influence found its way into evening gowns with huge spreading skirts and full sleeves. These were charming and becoming.

Fringe appeared, falling gracefully from shoulder and hip to floor. Romantic dresses full from the waist to the floor appeared. The picturesque dress which had been dormant for years became important and youthful as well.

Day clothes continued with a Russian Cossack influence, and also were adapted from the romantic men's costumes of the eighteenth century. Box suits were popular with younger women. Tunics appeared on day clothes and evening gowns. Trains for evening were longer than ever and slits in the skirts gave freedom of movement. Clothes had a gallantry, a dash, and a great deal of movement. Women had assurance and wore their clothes with knowledge and a feeling of freedom.

The silhouette also encouraged the revival and adaptation of fashions of 191o. This rather florid, but amusing era, was recon structed with a simplified modern treatment. The clinging body flaring into a series of frothy flounces below the knee dominated the scene. The shoulder continued being the object of rejuvena tion, and also swirled into flounces in the form of short capes both double and single of layers of chiffon, organdie, or velvet.

Amusing details were introduced for sport and beach. Rope was applied to linen pocketbooks, made into bracelets with wooden ornaments, and used as dress trimming. Blouses and entire dresses were made of interestingly woven string. Cello phane was woven into wool and made into street dresses. Eve ning gowns were made of light weight wools and linens. All of these things were revolutionary and contradictory. It became a year of inventiveness—a year of rather eccentric innovations.

continued to emphasize the swagger gallantry in dress. It also ushered in great collars and foolish hats. For once in the history of fashion, the ridiculous was worn with serious accept ance. As we glance over the pages of fashion history it is not uncommon to be highly amused at some of the eccentricities of a past, but rarely do we recognize this humour as we go about wearing the costume of the present. 1935, however, proved an exception. The millinery of the day was often completely mad. Fantastic bonnets were worn, pancakes of velvet or straw, flaring into points or wings as if a bird had lighted on our ladies' heads. In fact, humour appeared everywhere.

Drapery appeared again with a 1913 feeling. Ladies preferred to return to a gracious pre-war style of dressing—particularly in their evening clothes. Everywhere one heard of the draped sil houette. An East-Indian influence appeared, suggested by the dresses worn by the wife of a visiting East-Indian potentate. These modern dresses were made with the Indian sari attached, which was thrown over the head and fell to the feet. The clas sical influence also continued, developing a sweeping back full of dignity and grace. Quaint and rather ultra-sophisticated very feminine clothes appeared, inspired by Dresden figures and Eu genie portraits. It was the revival of a romantic era treated in a modern way. It became amusing and charming at the same time.

The Italian exhibition of art in Paris influenced both the de signers of clothes and materials throughout the world ; and thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth century Madonnas became modern ladies as seen through modern eyes. A military treat ment crept into day clothes, "frogs" across the coat fronts, braid, broad shouldered short jackets, small felt hats with showers of black coq feathers giving the illusion of Italian army officers. These things were probably inspired by the war clouds over Italy and Ethiopia. A mediaeval influence and an Italian Renaissance influence were strongly felt in evening clothes. These period in fluences were always approached and adapted in a contemporary manner giving them an extremely modern viewpoint. A feeling of great luxury and extravagance, particularly in the use of furs appeared to be a foremost thought in 1935. Silver fox skins were used in a most prodigious manner, being made into entire short coats for day and great capes for evening. (G. AD.)