Mass Size

SIZE, MASS, DENSITY AND FORM To primitive man the earth was a flat disk with its surface diversified by mountains, rivers and seas. The spherical form was asserted by Pythagoras, and Aristotle used arguments in its favour similar to those used today, viz., the ship gradually dis appearing, hull first, masts later, as it recedes beyond the horizon; the circular shadow cast on the moon during an eclipse ; and the alteration in the appearance of the heavens as one passes from place to place on the surface. With regard to the last point, we may notice that if the earth were flat any star above it would be visible from every point of it. This is not true : many of the stars visible in England are never visible in South Africa or Aus tralia, and conversely. On the other hand, an observer on the sur face of a spherical earth would see every star that is above the tangent plane to the sphere at the point where he is. The direr, tion of this plane varies with his position, and therefore the stars visible also depend on his position. The mean altitude (angular elevation above the horizon) of the Pole star is equal to the lati tude of the place, for observers in the northern hemisphere.

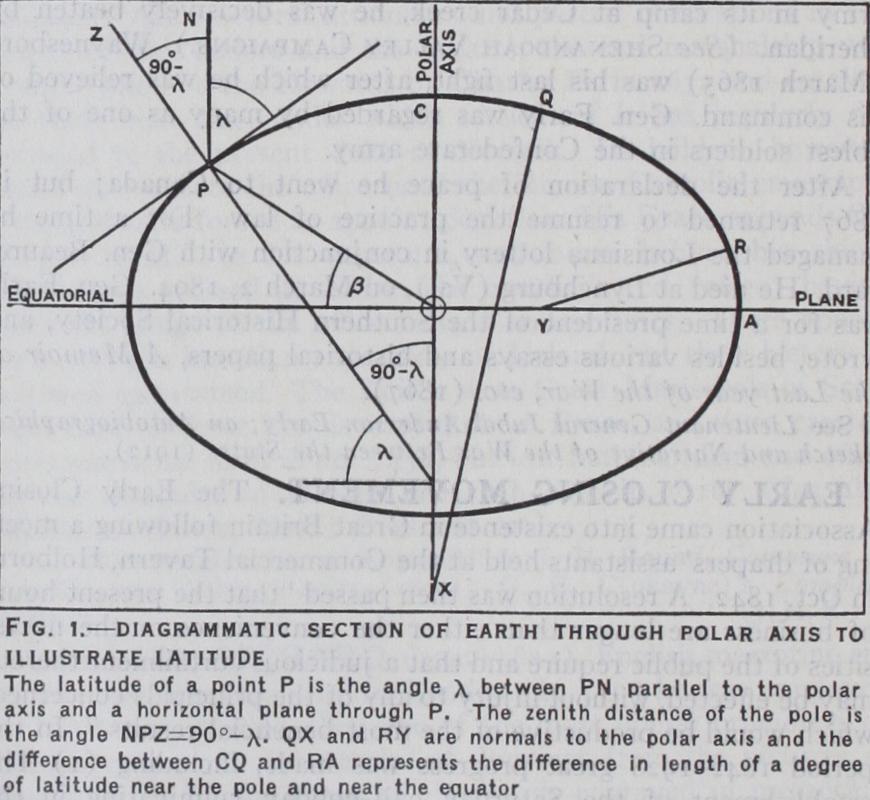

The spherical form did not, however, become generally believed until after explorers had actually sailed around the earth; though this argument is not intrinsically so conclusive as any of the three first given. The distance a traveller has to proceed northwards to make the mean altitude of the Pole star increase by I° is a "de gree of latitude." Eratosthenes, in 25o B.C. , was the first to meas ure this, by determining the difference of latitude between Alex andria and Syene, but there is some doubt about his measure ment of the distance between these places. Picard, in 1671, ob tained the first useful estimate. From the length of the degree of latitude the size of the earth can be calculated.

Actually, the length of the degree of latitude is found to vary slightly with latitude. This is because the earth is not exactly a sphere, a better approximation to its shape being an oblate sphe roid (the surface swept out by an ellipse rotated about its shortest diameter) . Such a surface is flatter near the pole than near the equator, and the degree of latitude is therefore longer in high latitudes than in low ones. Thus observation of the length of the degree in both high and low latitudes determines both the size of the earth and its polar flattening. The best determination yet made is that of J. F. Hayford, from observations in the United States, published in 1910. He gives: The distance from pole to equator, measured along the surface, is very nearly io,000 kilometres.

The mass of the earth is found by comparing its gravitational attraction on a small sphere at its surface with that of a large sphere of known mass on the same small sphere. The attractive force satisfies the law of gravitation, namely, that the force pro duced on a given small body is proportional to where mis the r mass of the attracting body and r the distance of its centre. If then the forces produced and the distances are known, we can find the ratio of the masses. Boys and Braun independently found the mass to be metric tons (1 metric grams= 0•9842 British ton). This is the mass of a body with a volume equal to that of the earth, and with a density equal to 5.527 times that of water. The mean density of the earth is therefore 5.527 gm. per cubic centimetre.

The motion of the earth is known if we know three things, which are independent or nearly so : first, the motion of its centre; second, its rotation about its centre ; third, any variations of shape that may be taking place. These three types of motion may be described separately.

Movement of the Earth as a Whole.

The most important part of the movement of the centre is the revolution about the sun. The centre of mass (i.e., centre of gravity) of the earth and moon together describes in the course of a year an elliptic path, with the centre of the sun at one focus. The mean distance from the sun is million km., or 92.82 million miles. The eccentricity of the orbit is 0.016751 (eccentricity=difference of greatest and least distances -: sum of greatest and least distances).The centre of the sun, however, is not fixed, but shares in the general motion of the solar system relative to the stars. The latter is a steady motion of the centre of mass of the whole system with a velocity of about 2okm. per sec. towards a point in the con stellation Hercules. It is found by statistical discussion of the apparent motions of stars. The sun's centre is close to the centre of mass of the solar system, but moves with regard to it on ac count of the attractive forces of the planets on the sun. The planets also attract the earth and moon. These forces introduce very complicated minor disturbances called perturbations.

The centre of mass of the earth and moon is about 4,80o km.

from the centre of the earth ; the latter moves about the former in the course of a month on account of the attraction of the moon for the earth, and on this account the earth gets alternately in front of and behind its mean position. This monthly inequality provides a means of determining the moon's mass.

Rotation.

The rotation of the earth about its polar axis is nearly uniform, the period being the sidereal day, which is 23h.

56m. 4.095s. of solar time. The revolution about the sun and the rotation were both established by Copernicus in In his great work De orbiurn coelestium revolutionibus it was shown that the common astronomical phenomena, such as the rising and setting of stars and the sun, the difference between the lengths of the sidereal and solar days, and the seasons, could be explained most simply by regarding the earth as revolving annually about a fixed sun, while rotating about an axis in itself. Later, the explanation of the revolutions of the planets was the greatest triumph of Newton's law of gravitation.

The position of the axis, however, varies. The disturbances are known as precession, nutation and the variation of latitude. Precession (often called precession of the equinoxes) is a motion of the earth's axis in a cone whose axis is perpendicular to the plane of the earth's orbit, so that the celestial pole appears to move in a circle about the pole of the ecliptic. The time taken for the complete revolution is about 25,800 years. The phenomenon was discovered by Hipparchus (12o B.e.), and was first explained by Newton. The attraction of the sun and moon on the earth's equatorial protuberance tends to make it move so as to bring the equator into the plane of the orbit of the earth or the moon respectively. But the earth's rotation introduces a gyroscopic control, and the ultimate result is that each point of the earth's axis moves parallel to the plane of its orbit. The explanation is similar to that of the motion of the axis of a spinning top. Gravity tends to make the axis move downwards, but the spin of the top converts the disturbance into a revolution of the axis about the vertical. One effect of precession is that the equinoxes move around the ecliptic so as to be always moving to meet the sun. The rate is 50".26 per year, enough to displace the equinoxes by 30° in 2,15o years. The vernal equinox, the point where the sun crosses the equator on its way north, was known in astronomy as the "first point of Aries"; but on account of precession it is now in Pisces. Also 4,000 years ago the star nearest the pole was a Draconis ; but since the pole has moved it is now a Ursae Minoris; in 12,000 years it will be Vega.

The force tending to alter the tilt of the axis is not constant ; when the sun or moon is crossing the equator, for instance, it has no effect. The path of the pole is therefore not described with uniform velocity, and is not quite a circle. The departures from the uniform circular motion are called "nutations." The largest of them, discovered by Bradley, is the lunar nutation, with a period of 18.6 years and an amplitude of 9"•2 in latitude. This arises because the plane of the moon's orbit revolves on the plane of the ecliptic in 18.6 years, so that the motion of the pole caused by the moon is not always about quite the same point of the sky. The variation of latitude consists of two small movements, one with a period of about 14 months, the other of a year. Both have amplitudes of about o"-1. The existence of the former was predicted on dynamical grounds by Euler; it is a circular oscil lation of the axis akin to the wobbling of a badly thrown quoit.

If

the earth were quite rigid its period would be 306 days; actually it is about 428 days, the difference being due to the earth's elastic yielding. The annual movement is due to seasonal displacements of matter over the earth's surface. Both were discovered by Chandler in 1891; the qualitative explanation is due to Newcomb.

Deformations.

In addition to the above general movements, the earth is continually altering its shape. The movements in volved in mountain formation and isostatic compensation are large but slow, taking millions of years for completion. The movement in a large earthquake may reach several metres close to the origin ; it starts suddenly and is soon over, but elastic waves are sent throughout the earth and produce small movements of the ground at great distances. The tidal forces of the sun and moon not only displace the water on the surface, but pull the solid earth itself somewhat out of shape ; this deformation is associated with an indirect one due to the weight of the displaced oceanic waters. All of these movements require either long inter vals or sensitive instruments to make them perceptible.There are several different sources of information which are available concerning the constitution of the earth. Starting with the geological evidence, we know that most of the land surface is covered with a layer of sedimentary rocks. The chief of these are sandstones and shales, produced mainly by the weathering of granite and related rocks and redeposition of the resulting sedi ments in shallow water. In addition, large areas within the con tinents are covered with ancient rocks akin to granite, and granite is also a common intrusive rock. For all these reasons geologists (following Suess) have come to believe in a widespread granitic layer under all the continents. Another very common intrusive rock is basalt, which exists in several different forms, such as dolerite, gabbro, eclogite and tachylite. It is denser, in its com monest forms, than granite (3.o against 2.7), and therefore has probably come from a greater depth. But the mean density of the earth is 5.5, nearly twice the density of basalt, and it has been shown that the high pressures in the interior of the earth are quite insufficient to compress basalt to such an extent. There must be much denser matter within the earth, and its density must be much greater than 5.5 to make up for the lighter stuff on the outside. This indicates an interior composed of heavy metals, especially iron, since this is the commonest heavy metal in the crust.

Upper Layers.

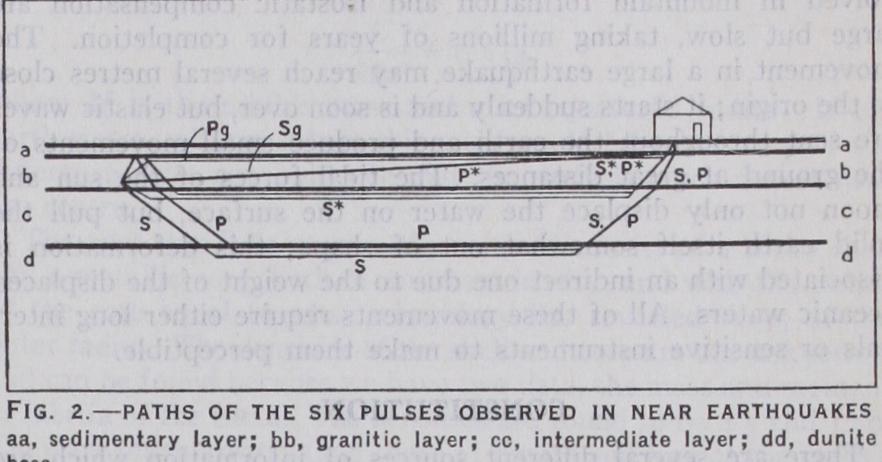

More detailed information is provided by seismology. As has just been mentioned, earthquakes send out elastic waves through the body of the earth, and the arrival of these at distant stations is recorded by instruments. Two types of bodily waves exist in a solid: first, a compressional wave like a sound wave, such that, as the wave passes, a particle vibrates in the direction of travel of the wave; and, second, a distortional wave, where the vibrating particle moves at right angles to the direction of travel of the wave. The two types are referred to, for brevity, as P and S. The letters stand for "primary" and "secondary" because the compressional wave travels faster. The velocities depend on the elastic properties of the material (incom pressibility and rigidity, or resistance to change of shape) and on its density. When the substance is not uniform the energy of each wave behaves very much like that of light : that is, it travels in rays, which are curved in such a way that the wave travels from one end of the ray to the other in a shorter time than it would take if it travelled by any slightly different path. As in the case of light, again, if there is a sharp boundary between two different materials, a wave reaching the boundary is partly transmitted and partly reflected. A complication arises, however; in elastic waves, in a solid, four waves arise at a boundary, a compressional one and a distortional one in each medium. The distortional wave is entirely characteristic of solids: it does not exist in a liquid.It is actually found, when the times of arrival of the waves from a near earthquake at different distances are compared, that a pair of waves can be traced, travelling with velocities of 5.4km. per sec. and 3.3km. per sec. respectively. The former velocity agrees with that found by L. H. Adams and E. D. Williamson, of the Geophysical laboratory at Washington, for the velocity of compressional waves in granite. This wave is consequently de noted by and the other, which appears to be the corresponding distortional wave, by . They travel wholly in the granitic layer from the origin to the observing station, apart from their short passage upwards through the sedimentary layer. These waves were first observed by A. Mohorovicic of Zagreb, Yugo slavia, in 1909.

If, however, a basalt layer underlies the granitic one it would be expected that some part of the waves sent out would be trans mitted into this layer, travel through it, and be refracted up again when they return to the boundary. Now actually not one, but two other pairs of waves can be traced ; they have been given specific symbols, and their velocities are: P*, 6.3km. per sec.; S*, 3.7km. per sec. ; P„ (or simply P) 7.8km. per sec. ; S,t (or simply S), 4.3km. per second. The curious fact is that none of these velocities fits that for compressional waves in crystalline basalt, as found in the laboratory, which is 6.9km. per second. The inference is that there is no widespread layer of crystalline basalt. The velocity of P* fits either tachylite, which is basalt in a vitreous, or glassy, condition, or diorite, a crystalline rock inter mediate in composition between granite and basalt. P„ has a very high velocity; the only rock that transmits waves with so high a velocity is dunite, a rare rock at the surface, but consisting almost entirely of the mineral olivine (Mg2SiO., and Fe2SiO4), which is fairly common as a constituent of mixed rocks. Eclogite, which has a similar composition to basalt, but a density of 3.3, may give a similar velocity, though it has not yet been examined for this purpose in the laboratory. There are thus two possible successions with increasing depth, both consistent with the seis mological data, namely, granite-tachylite-dunite and granite diorite-eclogite-dunite. The former was suggested by H. Jeffreys, the latter by Professor A. Holmes, and both views have arguments in their favour.

The six waves all appear to travel with uniform velocity, so long as the distance does not exceed about goo kilometres. But their times of arrival are related as if they had started at times differing by a few seconds. If A is the distance of an observing station from the "epicentre" (the point of the surface vertically above the origin), T the time of arrival at the station, and v the velocity of travel of the wave, we have where T„ is the same for all stations for the same wave, so that the wave appears to have started at time and travelled out with velocity v. But every wave has its own T, on account of the delay of the indirect waves in travelling down to the intermediate and lower layers, whereas the waves S, and come practically directly; just as walking to the next village may be quicker than travelling by train if one does not live near the station. These ap parent delays in starting provide means of estimating the thick nesses of the granitic and intermediate layers, which are found to be about 1 okm. and 2okm. respectively, under average continental conditions.

Below the ocean the structure must be somewhat different. Granitic rocks appear not to exist there, and basalt may come right up to the ocean bottom. On the other hand Holmes has suggested that there may be a thin upper layer of syenite, a rock resembling granite except that it contains no quartz. Direct seismological evidence is lacking, except that P, and S„ seem to have the same velocities as under the continents. The chief difference between continents and oceans is, then, that under the oceans the granitic layer is absent or very thin.

Deeper Portions.

At distances over 9ookm. the four waves S* have all disappeared or at least become able. But and S,, still exist. Their observed times of mission give a means of finding their velocities of propagation at great depths, which has been employed by E. Wiechert, B. berg, S. Mohorovicic and C. G. Knott. The velocities increase with depth, somewhat irregularly, to a depth of 0.45 of the radius, or 2,9ookm. ; that of P varies within this range from 7.3 to 13km.per sec.; the corresponding values for S are 4.35km. per sec. and 7km. per second. The increase is to be attributed mainly to an effect of the high pressure in increasing the stiffness of the material. There is no sudden change of velocity within this range of depth and the material is therefore probably of uniform composition, or at least its composition varies only continuously.

P

waves just reaching a depth of 2,9ookm. emerge at an angular distance of r o3 ° from the epicentre ; that is, the line joining the epicentre to the point of emergence subtends an angle of io3° at the centre of the earth. At greater distances P and S cannot be detected. P reappears at a distance of 144°, and can be traced from there to the antipodes, but S never reappears at all. This is what would be expected if the earth had a liquid central core, for the fundamental property of a liquid is its inability to transmit distortional waves. But other alternatives are just possible, and we cannot decide that the central core is liquid without discussing other evidence.

P

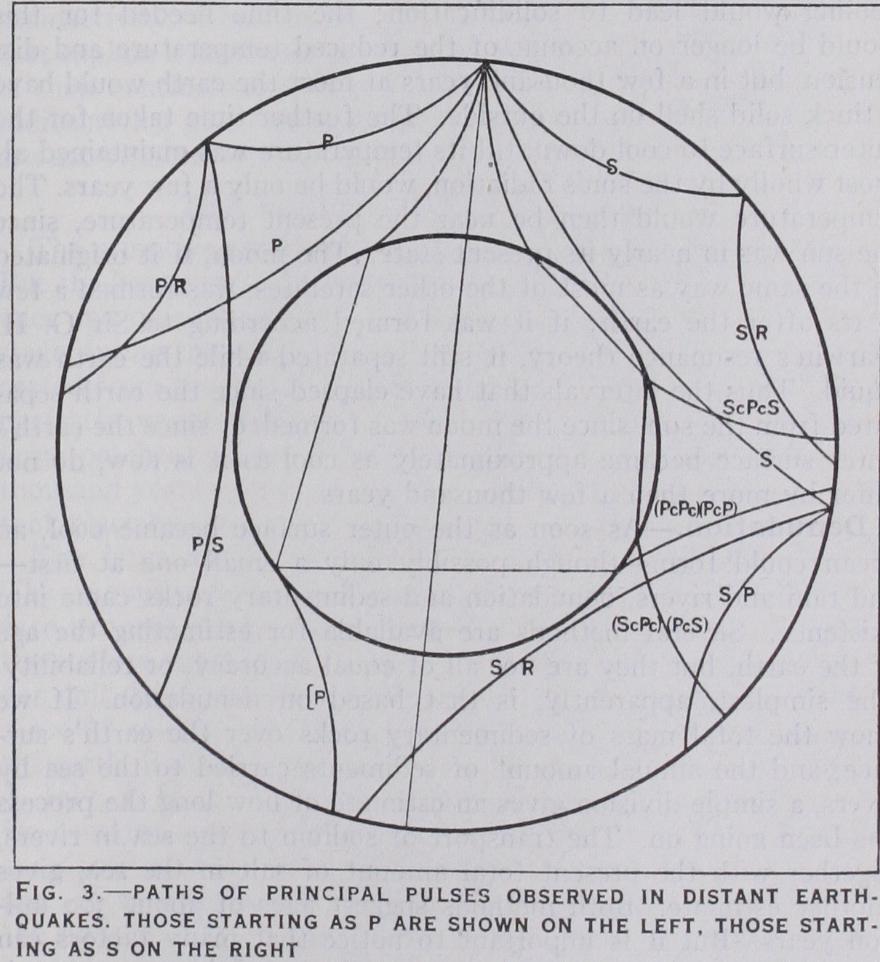

waves travel more slowly in the central core than just outside it, their velocity being about 9km. per second. These waves were first identified by R. D. Oldham in 1906, and further work on them has been done by Gutenberg and H. H. Turner. They emerge at minimum deviation at an angular distance of about 144°, and consequently have large amplitudes there. Between io3° and 144° only very small diffracted waves are recognizable. In addition, P and S waves incident on the central core are partly reflected and partly transmitted into the core as P waves. The reflected ones are spread out so much that they give rise to only small move ments at the outer surface, but they have been identified by V. Conrad, the discoverer of P*. The transmitted waves are more conspicuous. That derived from S is again broken up when it re turns to the boundary, giving three parts, denoted briefly by P, S, P and (S, (P, S). The first two re-enter the outer shell when the wave has passed through the core ; the three letters in each symbol indicate the type of the wave in the three parts of its path. The third wave is reflected on the inside of the core, and emerges after describing another path in the core as P and being transmitted into the shell as S. The existence of all these waves was predicted by Gutenberg, who calculated their theoretical times of transmission from the known velocities of P and S at various depths ; and they have all been found by observation at the pre dicted times by Gutenberg himself and other workers, especially Prof. H. H. Turner. The wave reflected at the inside of the core is interesting because reflexion would not occur if the transition was gradual ; it points to a sharp boundary between two quite different materials.

Density at Various Depths.

We have already seen that the high mean density of the earth also points to a difference of density between the interior and the exterior, comparable with that be tween metallic iron and ordinary rocks. There is reason to believe that the earth was once fluid, and in this state iron and silicates would not mix; thus a metallic core, sharply separated from a rocky shell, would be expected to exist. A correspondingly sharp change in properties with depth has been inferred, on entirely different evidence, from seismology. Seismology also indicates that there is no other sudden change. Hence we naturally infer that the two sudden transitions are identical, and that the thick outer shell, down to a depth of 2,9ookm., is composed of a silicate rock resembling olivine in composition, while the central core below that depth is made of metallic iron, probably in the liquid state.The theory of the figure of the earth leads to another datum, involving the earth's "moments of inertia." The moment of inertia of a body about a line is obtained by multiplying the mass of every particle of the body by the square of its distance from the line, and adding up for all the particles. The moment of inertia of the earth about the polar axis is denoted by C, and that about any diameter in the plane of the equator is denoted by A. C is greater than A be cause the earth is spheroidal; particles, on an average, are farther from the polar axis than from one in the equatorial plane. Now the rate of precession contains as a factor the ratio (C— A) C is therefore sometimes called the "precessional constant" or the "dynamical ellipticity." This rate being observed, and every other the precessional constant, which is • But can also be 305.6 found absolutely, because it is the only unknown in the formula for the variation of gravity over the surface of the earth. Hence C can be found by simple division. It is conveniently expressed by the equation where M is the earth's mass and a its equatorial radius. It the earth was a uniform sphere this ratio would have been o•400 ; the difference gives new evidence that the earth is much denser near the centre.

The next step is to assume the earth to consist of a rocky shell and a metallic core, both of uniform density, and with the radius of the core equal to what seismology has revealed—o•55 of the outer radius. The densities of the shell and core are our unknowns, and can be found because we have two data, the mass and moment of inertia of the earth. The densities are found to be 4.5 and 12.0. They are much greater than those of dunite and iron at the earth's surface. But in the earth every layer is compressed by the weight of the matter above it, and if we allow for this we find that the average densities would be very close to those found for the uni form shell and core.

The Bodily Tide.

The density and the velocities of propaga tion of the P and S waves at any depth being by this time fairly accurately known, the elastic constants (the incompressibility and the rigidity) of the matter can be found. Hence it becomes, theoretically, possible to calculate how the earth as a whole would yield under known forces. The r4-monthly variation of latitude and the tides both provide data capable of being compared with theory. If the earth were perfectly rigid, the period of the varia tion of latitude would be 306 days; if it were a fluid, the variation of latitude would not exist. If, again, the earth were fluid, the in terior would yield so much to tidal forces that the ocean could yield no more, and there would be no visible tides. The actual tides are about 0.7 as high as they would be on a rigid earth. The two sources of information are closely related, but do actually give distinct checks on any theory. Lord Kelvin showed that the tidal yielding of the solid earth was no more than that of a globe of steel of the same size. We know now, however, that the dunite at a depth of 3o-4okm. is about two-thirds as stiff as steel, and the matter 2,9ookm. down is fully twice as stiff as steel. If the central core were equally stiff, it can be shown that the earth as a whole would yield less than tides and the variation of latitude show it does. It has not yet been definitely shown that a liquid central core would give complete agreement, but it would certainly fit the facts much better than any reasonable hypothesis consistent with the solidity of the core.