Observation of Solar Eclipses

OBSERVATION OF SOLAR ECLIPSES In general little or nothing of astrophysical importance can be learnt from a partial eclipse of the sun, but during the few min utes of totality of a total eclipse much information about the physical nature of the sun has been obtained that is not available under any other circumstances. The observation of the times of occurrence of the various phases of any eclipse is useful in im proving our knowledge of the motions of the sun and moon and of the figure of the earth, but the value of a total eclipse is that we can then observe the solar atmosphere and surroundings which are invisible to us ordinarily on account of the great brilliance of the general sky-light, i.e., sunlight scattered by the molecules of the earth's atmosphere. The moon acts as a screen outside the earth's atmosphere and cuts off the direct light of the sun and the scattered light at the same time, thus for instance the Corona (q.v.) has never been seen or photographed except during an eclipse.

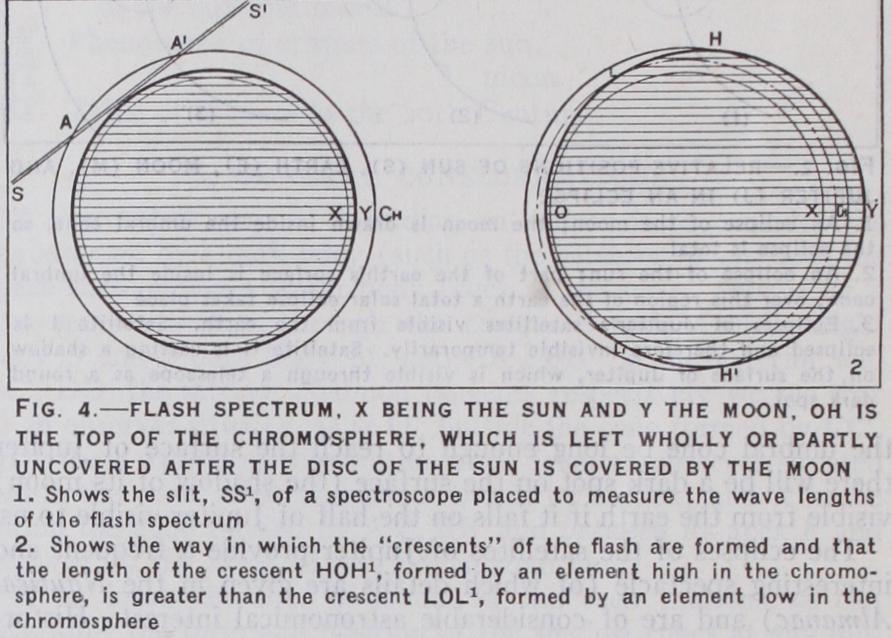

The apparent diameter of the sun is very roughly 1,800 sec. of arc and its atmosphere, or the Chromosphere (q.v.), extends about 10 sec. only above the surface (photosphere) ; that is to say the sun as seen from the earth is a disc surrounded by a narrow ring of atmosphere somewhat over 1% of a solar diameter in thickness. This atmosphere consists of many elements in the gaseous condi tion at a high temperature. We cannot in ordinary circumstances see it although it is very bright, but during a total eclipse the moon covers up the disc of the sun, and when the last crescent of the disappearing sun has vanished the narrow ring or crescent of chromosphere becomes visible. It is found that this atmosphere yields an emission spectrum which is the reversal, or counterpart of the ordinary solar absorption spectrum. On account of the fact that this spectrum flashes out at the instant totality commences it is termed the "flash spectrum." The study of it is one of the most important aims of eclipse observers. First of all it is of prime importance to have an accurate knowledge of the wave lengths of the lines in this spectrum. For this purpose an image of the sun is focused on the slit of a suitable spectrograph, and a suitable comparison spectrum may be photographed alongside the flash spectrum. In this way the bright lines in the flash spectrum are identified line for line with the dark lines in the Fraunhofer spectrum.

From fig. 4 (1) it is clear that the length of the line in the spec trum, i.e., the length of slit (SS') illuminated (AA') depends on the height of the chromosphere. This method has also been used to estimate the heights to which the elements concerned reach in the chromosphere since the intensity diminishes as the height in creases, but it is open to serious objections. Firstly there exist lines of any one element of greatly different intensities at any one level and the length of a line in the spectrum will depend on whether or not the light is strong enough to produce any effect during the exposure given. Secondly the scale of image possible renders it almost impossible to make a really accurate setting of the slit at a given height, and as a corollary of this it is usually entirely unknown to what extent the moon has cut out the central part of the line during the exposure. Lastly the slit is by no means narrow compared with the chromosphere itself and the optical definition obtainable may be such as to confuse the image seriously.

The chromosphere is so narrow that its spectrum can be ob tained with an objective prism spectroscope (i.e., one without slit of collimator) . Fig. 4 (2) shows the way in which the moon leaves a crescent of chromosphere uncovered at a given instant. The lengths of the crescents again depend on the height of the element concerned. This method is used to determine heights in the chromosphere. It is open to the first objection raised against the slit method, but not to the others, and enables us at any rate to fix a minimum height. It is found that most elements extend to a height of about 500 km. (310 miles) but some, e.g., H and Ca are found as far up as 14,00o km. (8,700 miles). The best method for investigating the variation of intensity with height is un doubtedly that known as the "falling plate method." For this purpose an objective prism or grating is used giving in the usual way a spectrum of crescents, but a part of this only is used, namely a narrow strip of it which is allowed to pass through a slit running along the spectrum area placed close to the plate. The plate is caused to move uniformly during the period of exposure and thus each small piece of crescent (virtually a dot) is spread out into a long line perpendicular to the direction of dispersion in the spectrum. Since as the exposure proceeds the chromosphere is gradually covered up at a known rate from the bottom by the moon (or uncovered if third contact be used) the variation of intensity along the line so produced can be used to determine accurately the law of variation of intensity of the radiation of the wavelength concerned with height.

It is only recently that modern spectro-photometric methods have been applied to the study of the flash spectrum, but the results are most promising and photometric investigations will form an important part of future observations. One serious diffi culty is to compare the intensities of lines that are not so close together that the variation of the absorption of light in the earth's atmosphere can be neglected, since the precise value of the absorp tion at different wave-lengths is unknown. It should be remarked that the method of obtaining flash spectra with a slit can be used when the eclipse is not total, by setting the slit on a part that will be covered by the moon.

There appears to be a faint general continuous background to the flash spectrum, but near the head of the Balmer series there is a marked continuous spectrum due to the capture of free elec trons by the ionized hydrogen atom. The Balmer series of hydro gen is extraordinarily well developed in the flash and if the lines be numbered in order taking as H,, Ho as and so on we can detect lines as far as This confirms our ideas of the very low density in the chromosphere.

totality commences an irregular fringe of crimson flame-like objects is often seen around the limb of the sun. These are the prominences, and are found to consist of masses or clouds of gas mainly hydrogen (hence the red colour) and calcium in rapid motion above the solar surface. They vary very much in size and profusion, being found mostly in the sun spot zones and in greatest profusion and usually largest near a time of maximum sun-spot activity. During a long eclipse changes may be found in the prominences, but the study of their behaviour is carried out mostly with the spectroheliograph, an instrument which allows them to be photographed without an eclipse. Pl. II., in the article SUN shows a prominence photographed in 1919. The same prominence was observed with the spectroheliograph at the Solar Physics Observatory, Cambridge, on the day preceding the eclipse and was photographed at intervals of an hour throughout the day of the eclipse whereby remarkable changes were observed and it was found that this giant prominence reached a height of i 50,00o miles above the solar surface, attaining a velocity of over S5,000 miles per hour and a maximum length of 361,000 miles.

The Deflection of Light by a Gravitational

of the most famous, and the first, of the tests of Einstein's theory of relativity was that of observing the bending of a ray of light passing close to the sun. During a total eclipse the brighter stars are visible to the naked eye and many more can be photographed near the sun. If Einstein's theory be true the stars near the sun should be found not in their true places but displaced away from the sun by a small, but measurable, amount varying inversely as the distance from the centre of the sun. This test was first carried out in 1919 and has been repeated since with results on the whole in favour of the theory (see RELATIVITY).

Other

Beads.—It is found that totality does not begin or end quite suddenly as it should were the sun and moon of perfectly smooth outline, but that there exists for a moment or two a crescent of minute gleaming points of light, called Baily's Beads. These are due to the irregular outline of the moon (i.e., its mountains and valleys) whereby the sun is left uncovered here and there for a moment after the disc representing the size of the moon if smoothed out would have covered it.Shadow Bands.—When totality is nearly due and there remains but a small crescent of sun left there can often be seen on the ground or on the walls of buildings striations of light and shade, not very definite in outline but something like a sheet of cor rugated iron, moving moderately rapidly perpendicular to their length. These are termed the shadow bands and are due to cor rugations introduced into the nearly plane waves of light reaching us from the sun owing to irregularities in the refraction of the earth's atmosphere.