Operations in East Africa

EAST AFRICA, OPERATIONS IN. When the World War broke out in 1914 the garrison of British East Africa, the territory immediately north of German East Africa, was scattered and engaged on punitive expeditions remote from the enemy fron tier. In the case of each Protectorate the troops were native with European officers. The German forces, some 5,000 strong, includ ing 26o Europeans, lay ready to the hand of their commander, Von Lettow-Vorbeck, a capable and determined soldier well able to employ them to full advantage. If it is remembered how keenly sensitive the native soldier is to any shortcoming in his superior and that Von Lettow had only been with his command for six months when hostilities began and kept that command efficient and formidable through four years of steadily declining fortune, some idea may be formed of the resolute nature and soldierly qualities of the German commander-in-chief. His opera tions consistently bore the clear imprint of his skill and person ality, and there were advantages, other than his professional capacity and steady courage, upon which he could rely.

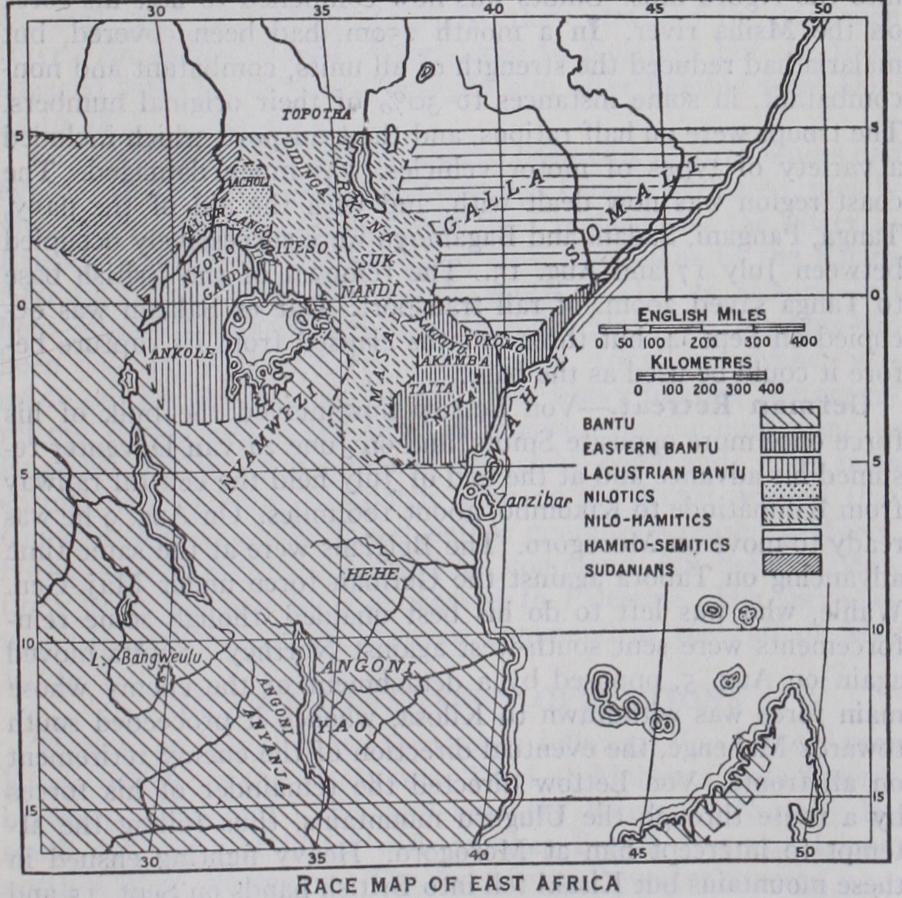

The country—nearly double the size of Germany in I 9 4 which was the scene of operations, is for the most part covered by bush, dense as a rule, but occasionally thinning out to some thing like park land. High mountain ranges, thick with vegeta tion, rear themselves from bush and jungle which are fever stricken and liable to wholesale inundation during the rainy season. Rivers abound and malaria and dysentery of a malignant type, with other tropical diseases, combined to swell the casualty list of a European or Anglo-Indian force. Practically every animal im ported into East Africa for the use of the British forces suc cumbed to the tsetse fly. The route of every British advance was marked by casualties due to diseases from which the rank and file of the enemy—askaris recruited from local tribes—were im mune. Surprise by the attacker was as difficult as it was simple by the defender, who waited concealed and warned by the labori ous approach of his adversary cutting roads and bridging rivers.

Supply and transport presented appalling difficulties to an ad vance through hundreds of miles of naturally impenetrable bush, while the defending force slowly fell back upon the magazines posted in its rear. Only an overwhelming preponderance in num bers made any advance possible, but a force starting with a strength adequate for an offensive enterprise constantly found itself reduced at best to an equality of strength on contact with the enemy. Many good cards were thus in the hand of the Ger man commander ; and he rarely failed to play them with full effect.

Naval Operations and German Advance.—On Aug. 8, 1914, two British cruisers, "Astraea" and "Pegasus," arrived opposite Dar es Salaam from Zanzibar, and, being unable to leave a garrison, the naval commander covenanted with the German governor that the latter should forbear from any hostile action in Dar es Salaam itself. Parallel to the southern frontier of British East Africa and about 5om. distant from it ran the Uganda railway from Mombasa to Lake Victoria. This tempting and exposed objective, for the protection of which the British troops at the outset were hopelessly inadequate, at once appealed to Von Lettow, who on Aug. is seized Taveta, which lay in British territory at the eastern end of the gap between the southern slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro and the northern end of the Pare mountains in the German Pro tectorate. An enemy force here was a standing menace to the British capital at Nairobi, and constantly raided the railway line.

In September the enemy cruiser "Konigsberg" returned to Dar es Salaam and on Sept. 20 surprised and destroyed the "Pegasus" while undergoing repair in the Zanzibar roadstead. A combined enemy operation against Mombasa, for the execution of which the "Konigsberg" was to attack the port in conjunction with a land force moving north along the coast, failed, as the "Konigsberg" was driven by the ships of the Cape Squadron into the Rufiji delta, where she was run aground. The land force began its march along the coast on Sept. 20, was repulsed at Gazi, 25m. from Mombasa, on Sept. 23, and retired to the frontier on Oct. 8. The crew of the "Konigsberg," which was blown up in July 1915, after being set on fire by the monitors "Severn" and "Mersey," joined the enemy land forces, with an armament of ten 4.1 guns.

German raids along the coast, on the Uganda railway, and into the frontier districts of Uganda, Belgian Congo, Rhodesia and Nyasaland were frequent in the opening months of the campaign. These small enterprises were much simplified by the central posi tion of the enemy and the excellent lateral communication afforded by the central railway from Dar es Salaam to Kigoma, on Lake Tanganyika. This lake was under German control until Dec. 1915, when by the operations of motor boats specially brought from Capetown the enemy was deprived of the one lake which had not been in British hands since the earliest days of the campaign.

Reinforcements from India.—It soon became apparent that, unaided, the British Protectorate forces could not hold their own, and the Government of India consented to send an expedition. On Aug. 25 its leading unit reached Mombasa with Brig.-Gen. Stewart, who assumed command. The rest of the expeditionary force was directed on Tanga, the northernmost German port, at the southern extremity of the Usambara mountains, healthy high lands where the bulk of the German settlers resided. Coincident with an attack on Tanga an advance against Moshi by the north of Kilimanjaro was to be made by Stewart. The expeditionary force under Brig.-Gen. A. E. Aitken was about 7,00o strong and (except the 2nd Loyal North Lancs.) composed of Indian troops.

Failure of British Offensive —The transports reached Tanga on Nov. 2, when the local commissioner represented the place as an open and undefended port and bombardment was deferred. Meanwhile, Von Lettow, advised of the plan by captured Indian mails, was hurrying reinforcements to the coast. When one and a half British battalions landed two miles east of the town on the evening of the arrival, they met with strong opposition and fell back. Von Lettow arrived on the evening of the following day, when British reinforcements had been landed and fighting re sumed, and on Nov. 4 heavily defeated his opponent, whose casualties were 795. On the same day Stewart, checked at Longido, was compelled to retire. The British force at Tanga re-embarked and reached Mombasa on Nov. 5. The first British offensive had thus failed completely. Von Lettow's success at Tanga put an end for the time being to any general offensive against him, and it was not until 1916 that the next British advance was set in train.

The intervening period was occupied in raiding by both forces, with occasional engagements of a more ambitious nature. A British force was compelled to surrender on Jan. 17, 1915, at Jasin, in enemy territory, to a superior force, after 48 hours' fighting, which exhausted their ammunition and water. German losses, especially in officers, were serious, as was the shrinkage of ammunition. Maj.-Gen. M. I. Tighe assumed chief British com mand in April 1915 and in June, Bukoba, on Lake Victoria, was taken.

Reinforcements Arrive.

Aid was now sought from a differ ent quarter, for, with the conquest of German South-west Africa by General Louis Botha in July 1915, the resources of the Union of South Africa became disposable to an extent which was im possible till the disappearance of the enemy from her own border. During the latter half of 1915 there was continuous preparation in South Africa of troops, depots, supplies, medical stores, trans port, animals and material of all kinds for use in East Africa. By Feb. 1916 one mounted brigade, two infantry brigades and one field artillery brigade, complete with all their auxiliary units, had arrived from South Africa to join Tighe. A second mounted brigade followed, together with a battalion of the Cape Corps (coloured men from the Cape Province). Tighe also had the fol lowing European units : the Calcutta Volunteer Battery, the 2nd Loyal North Lancs., 25th Royal Fusiliers, 2nd Rhodesians and two local settlers' corps; India sent him from her native army ten infantry regiments, one squadron of cavalry and two mountain batteries. The battalions of King's African Rifles were the orig inal native Protectorate force. At the same time, Von Lettow's force had reached the highest limit which it attained in the cam paign and was probably over 20,000. The exact combatant strength is difficult to estimate, for there were many carriers of whom a percentage were armed and many trained as askaris. The askari in his own country is a soldier of high value. Such a force, with a strong leaven of Europeans, under a skilful and determined com mander, was a formidable adversary in tropical bush country.

German Ammunition Supplies.

In April 1915 the mind of Von Lettow, which had been sorely exercised by his shortage of ammunition, was relieved in the following remarkable manner: A British ship, the "Rubens," seized at Hamburg, left that port loaded with arms and ammunition and appeared off Tanga on April 4, being sighted by H.M.S. "Hyacinth." Entering Manza Bay on fire and abandoned, she was boarded by bluejackets, who found her timbered up and battened down. After firing more rounds the "Hyacinth" steamed away on the assumption that her quarry would burn herself out. The Germans returned and salved almost the entire cargo, and a largely increased volume of enemy fire from the Mauser pattern 1898 rifles which the "Rubens" had brought was the result. This operation was repeated a year later.The chief command in East Africa was assumed by General Smuts in Feb. 1916. He had previously declined the post, but when General Smith-Dorrien was compelled to relinquish the command in consequence of illness he accepted it. He reached Mombasa on Feb. 19 and found the railway completed from Voi to Serengeti, 5m. from Salaita Hill, the German advanced posi tion from Taveta. A week earlier an attack on Salaita had failed. The rainy season was at hand and movement would then become impossible ; Smuts telegraphed to Lord Kitchener that he was ready to carry out the occupation of the Kilimanjaro area at once. The proposal was agreed to and Smuts proceeded to advance.

British Advance on Taveta.

An attack, designed primarily to hold the enemy, was to be delivered on Salaita by a force under General Malleson, while Stewart was to repeat his attempt of 1914 to reach Moshi by the north of Kilimanjaro and thence to intercept any enemy retirement in his direction. General van Deventer with a mounted brigade, moving by Malleson's right, was to cross the Lumi river, and by way of the foothills of Kilimanjaro cut the enemy line of retreat between Taveta and Moshi. The execution of this movement unobserved was the only chance of surprising the enemy, for it was apparent to Von Lettow, who had made all preparations for retirement, that Taveta was Smuts' objective. This surprise was effected. Van Deventer moved on March 8 and on the following day his troops were astride the Moshi-Taveta road. On the same day the Germans evacuated Salaita and took up new positions on two hills, Latema and Reata, covering the gap between the Pare mountains and Kilimanjaro. The main enemy force was posted at Himo, 5m. from the gap, whence it could move in any direction to attack or retire. The progress of Stewart's force was so slow that his movement was without effect.The new enemy position was attacked on March 1 1 and, after severe fighting all day and the succeeding night, was occupied on the morning of the 12th by a general advance in support of de tachments which had won their way to the two crests during the night and caused a retirement by the enemy.

German Withdrawal.

Von Lettow now withdrew his entire force to a position (Kahe-Ruvu) which stretched south of the Taveta-Moshi road from Kahe railway station eastward along the northern end of the Pare mountains. He was followed up and attacked on March 18 from Latema Nek by Brig.-Gen. Sheppard, and on March 20 van Deventer was sent from Moshi to turn the enemy at Kahe. He seized Kahe on March 21 and on the follow ing night, after a very severe action with Sheppard, the enemy withdrew to Lembeni, tom. S. of Kahe. Von Lettow abandoned one 4.1 gun, and had expended ammunition to an extent which he could ill afford, but his force was intact and the timely arrival of the second blockade runner at this juncture with four 4.1 field howitzers, gun and small-arm ammunition, machine-guns, stores, provisions and clothing was an inestimable stroke of good fortune. Here the operations which had been undertaken before the rainy season were concluded and the British forces took up positions covering Taveta and Moshi and facing the enemy at Lembeni.During the ensuing rains Smuts reorganized his force and pre pared to resume the offensive at the earliest possible date. He could rely for assistance in his main operations upon the Belgians in the north-west and the British force under Maj.-Gen. Northey, operating from Nyasaland, to the south-west. For reasons fully recorded in his dispatches, Smuts decided at once to send van Deventer with a mounted force rapidly by Arusha to Kondoa Irangi and thence to the central railway and east along that line to Morogoro. His own force was to move south by the Pangani, and make for the same ultimate objective, Morogoro. It was hoped that Von Lettow would there be brought to bay by the two converging forces.

New British Offensive.

Van Deventer moved on April 3 and occupied Kondoa Irangi on April i 9, capturing the enemy garri son at Lol Kisale en route. He reached Kondoa Irangi after heavy casualties in men and animals from disease and was there cut off and reduced to immobility as a consequence of his losses and the advent of the rainy season. Von Lettow concentrated a force against van Deventer and fighting ensued, but the Ger man attacks, with one exception, lacked vigour and were all re pulsed. Van Deventer's position was eased by the end of May, when Smuts began his advance down the Pangani and the Bel gians moved on Tabora. Maj. Kraut was in command of the German force opposite Smuts when the latter set his troops in motion southwards from Moshi on May 18, Von Lettow having assumed direction of his concentration against van Deventer.Systematically outflanked by his opponent, whose main advance along the Pangani was supplemented by flank movements by the Pare and Usambara ranges, Kraut found himself compelled to leave the Tanga railway and retire upon Handeni. This place was seized by Smuts on June 19, Korogwe having been occupied four days earlier. On June 24 the Germans were attacked simul taneously on three sides, but, after determined fighting, withdrew into the Nguru hills. Smuts was now compelled to halt his force on the Msiha river. In a month 25om. had been covered, but malaria had reduced the strength of all units, combatant and non combatant, in some instances to 3o% of their original numbers. The troops were on half rations, and the transport, which included a variety of types of motor vehicles, was much damaged. The coast region was now dealt with, and with the aid of the navy, Tanga, Pangani, Sadani and Bagamoyo were successively occupied between July 17 and Aug. 15. The removal of the British base to Tanga saved zoom. of rail transport. Dar es Salaam was oc cupied on Sept. 4, but three months elapsed from its capture be fore it could be used as the base.

German Retreat.

Von Lettow now moved the bulk of his force once more opposite Smuts, and on June 24 van Deventer re sumed his advance and at the end of July held the central railway from Kilimatinde to Kikombo, about 1 oo miles. On Aug. 9 he was ready to move on Morogoro. The Belgians were at the same time advancing on Tabora against the German force under Maj.-Gen. Wahle, who was left to do his best unaided, though some rein forcements were sent south-west against Northey. Smuts moved again on Aug. 5, opposed by a detachment of the enemy whose main force was withdrawn to Kilosa, whence it proceeded south towards Mahenge, the eventual direction of the enemy retirement on all fronts. Von Lettow directed the remainder of his forces by a route through the Uluguru mountains, thus foiling the at tempt to intercept him at Morogoro. Heavy fighting ensued in these mountains but Kisaki fell into British hands on Sept. 15 and Von Lettow retired to Mgeta river and there entrenched himself. On this front, during the last three months of 1916, activity was confined to such minor affairs as are usual between opposite en trenched forces. Civil administration was instituted in the occu pied area behind the British forces.

Belgian Operations.

The Belgian force (also native), under Maj.-Gen. Tombeur with European officers, was divided into two brigades, the Northern (Col. Molitor) and the Southern (Lt.-Col. Olsen) and operated in the north-west of German territory, op posed by Wahle, who was instructed to avoid a decisive action. The Belgian operations, well planned and successfully executed, were of prime importance to the general campaign. Broadly de scribed, they were as follows. Molitor invaded Ruanda by the north of Lake Kivu while Olsen co-operated south of him by the north of Tanganyika. The movements started on April 4, and by the end of May the Belgians were in possession of Ruanda. Moli tor then sent columns south-west to join hands with Olsen and other columns south-west to Lake Victoria, which was reached on June 27.In the middle of July, on a front between Tanganyika and Vic toria, Molitor and Olsen moved south on the respective objectives of Tabora and Kigoma, the terminus of the central railway on Tanganyika. Olsen occupied Kigoma on July 28 and Ujiji on Aug. 2, and then moved east on Tabora. Co-operating with Moli tor was a British column under Brig.-Gen. Sir C. P. Crewe, who captured Mwanza on the southern shore of Lake Victoria on July 14. On Sept. 19 Molitor occupied Tabora which Wahle had evac uated the previous day, leaving behind his sick with civilians and prisoners of war. Crewe reached the central railway a week later.

British Advance from Rhodesia.—By this time Northey had succeeded in interposing some of his forces, which were in three columns under Lt.-Cols. Hawthorn, Murray and Rodgers (the last a South African unit), between Tabora and Mahenge. His advance was on an original front between Lakes Nyasa and Tan ganyika. Murray occupied Kasanga (Bismarckburg) at the south end of Tanganyika on June 8. The Germans were defeated at Malangali on July 24, and on Aug. 29 Iringa was occupied, Lupembe having been seized ten days earlier. Northey, ordered with van Deventer, now at Kilosa, to deal with the enemy in the Mahenge district, was much outnumbered by forces already in touch with him and Wahle's columns approaching from the north, and on the night of Oct. 21 most of Wahle's troops broke through him. On the same day Kraut was heavily defeated at Mkapira. Hawthorn secured the surrender of an enemy column at Ilembule. On Dec. 24 van Deventer and Northey attacked the Mahenge force. An enemy column surrendered to Northey, but the force engaged with van Deventer escaped him after fighting from Dec.

25

to 28.Position at End of 1916.—By the beginning of 1917 Smuts had evacuated 12,000 to 15,00o white troops (South Africans), mostly victims to malaria, and they had been replaced by the Nigerian Brigade (Brig.-Gen. Cunliffe) and fresh battalions of the King's African Rifles. Kilwa and Lindi, south of Dar es Salaam, had been seized by the navy and a force under Maj.-Gen. Hoskins had been concentrated at Kilwa. On Jan. 1, 1917, an advance was made on the Mgeta position, but after heavy fighting the enemy retired across the Rufiji at Kibambawe. Smuts now went to England and Hoskins assumed the chief command. The rains ensued, and to clear the north bank of the Rufiji was all that could be barely accomplished before operations ceased perforce. Hoskins completely reorganized his command, but before opera tions were resumed he was ordered to Palestine. His successor was van Deventer, who assumed command at the end of May 1917. ---- - The enemy forces were disposed as follows : Von Lettow near Kilwa, Wahle in the Lindi area, Tafel at Mahenge, detachments between Kilwa and Lindi, and near the Ruvuma. Northey lay south and west of Tafel with another British force at Iringa, north-west of the enemy. The rest of van Deventer's troops were to act against Von Lettow. In pursuance of this decision an ad vance was made by the Kilwa force under Brig.-Gen. Beves on July 5 towards Liwale. The enemy fell back to Narungombe, where a severe engagement took place on July 19. The enemy re tired south, but the Kilwa force was unable to move again until mid-September. In August the enemy was driven from the Lukuledi estuary to allow of an advance inland from Lindi. The Kilwa force (Hannyngton) was to move south and that at Lindi (Beves) west. These operations were marked by the hardest fighting of the whole campaign. Von Lettow fell back, under pressure by Hannyngton, towards Nyangao, 4om. S.W. of Lindi, Wahle retiring before Beves. On Oct. 15 a four days' battle began between Beves' force and the enemy under Von Lettow joined by Wahle. The latter retained their position and it was ten days before Beves' force under the command of Cunliffe could re sume the offensive.

On Oct. 8 Tafel, pressed by Northey with Belgian co-opera tion from the north, had retired from Mahenge, and, breaking through two weak detachments on Nov. 16, moved south-east towards Von Lettow, whom he was debarred from joining by the Kilwa force. Vainly endeavouring to join the main body, Tafel reached the Ruvuma, but, unable to procure food, surrendered with his entire force on Nov. 28.

Germans Retire to Portuguese Territory.—On the night of Nov. 25-26 Von Lettow, having shed all weaklings, crossed the Ruvuma into Portuguese territory and thenceforward moved as the circumstances of his position, without bases and short of am munition, dictated. Early successes in the new sphere of action, especially at Ngomano, gave the Germans food, ammunition, arms and clothing, and when the rainy season set in, in Jan. 1918, they were able to rest for a short time.

The operations during 1918 were carried out almost entirely by natives, the King's African Rifles, and Von Lettow fell back upon guerilla tactics. Against him in Portuguese territory were sent columns from the east and south shores of Nyasa ; and an other (Brig.-Gen. Edwards) advanced west from Porto Amelia midway between the Ruvuma and Mozambique. After various engagements Von Lettow marched in May south to the Lurio river, 2oom. from German territory, captured Ille, and in June reached the coastal region near Quelimane. On July i he captured Nyamakura, 25m. from Quelimane, and in the middle of August at Chalana, eluded envelopment by converging columns. Turning north-west, he was engaged by Hawthorn (who had succeeded Northey) at Lioma, east of Lake Shirwa. After several en counters, the German force reached the Ruvuma again on Sept. 28 and, after resting at Ubena, where Wahle was left, set out for Rhodesia. On Nov. 1 Von Lettow made an unsuccessful attack on Fife and, turning south-west, took Kasama on Nov. 9. Ad vised on Nov. 13 of the Armistice, he accepted it the following day, and on Nov. 23 formally surrendered to General Edwards at Abercorn. With him were Dr. Schnee, the governor, and Maj. Kraut, together with a force of 3o officers and 125 other Euro peans, 1,165 askaris and 2,891 other natives (including 819 women), I small field gun, 24 machine-guns and 14 Lewis guns.

Troops Engaged, Casualties, Etc.

The troops employed by the Allies in East Africa included 52,339 sent from India ( 5,403 British) and 43,477 South African whites. East African and Nyasaland settlers, Rhodesian volunteers and the 25th Fusiliers numbered about 3,000; African troops (King's African Nigerians, Gold Coast Regiment, Gambia Company, Cape Corps) and West Indians about 15,000 ; an approximate total of 114,000 not reckoning Belgian native troops (about 12,000 in all), Portu guese and the naval force engaged. The greatest number in the field at any one time, May to Sept. 1916, was about 55,000; the lowest, in 1918, 10,000, all African, save administrative services. See also KENYA COLONY; TANGANYIKA TERRITORY.British and Indian casualties were returned at 17,823 ; of these 2,762 were in the South African Forces. These figures are exclu sive of casualties among carriers and of deaths and invaliding through sickness, which among the South Africans alone exceeded 12,000. The cost of the campaign to Great Britain, inclusive of Indian and South African expenditure and that of the local pro tectorates to March 1919, was officially estimated at £72,000,000.