Petroleum Drilling

DRILLING, PETROLEUM. Modern automatic rotary drilling has supplanted to a remarkable extent former methods of cable tool or "rod and drop tool" systems. (For details of this, as well as other methods of boring, see BORING.) It is the ex tension and perfection of automatic drilling that has been respon sible for the opening up of oil pools at greater and greater depths. Electric drive for both rotary and cable tool drilling has become common practice, whereas in the early 1920S it was an innovation and experimental. Before automatic machinery could be put to work on so complex and difficult an operation as deep-well drilling there was required the development of specially designed motors, first applied to well pumping, field water supply, Dipe-straighten ing machines, cutting and threading machines, and finally to drill ing. Rotary drilling required the development of adjustable speed motors and reduction gears of new type, and cable tool drilling, the development of an electric drive and control designed to give motion for drilling; power and high speed for pulling tools, bailing and setting casing, and slow speeds for ramming bits. With the first successful electric rotary deep-well drilling opera tion in California in 1923, a new era in drilling technique, based on automatic operation and simplicity of complete control, began. To see these modern plants in operation, drilling to depths of from 5,000ft. to I o,000f t. or even 15,000f t., is to get the full effect of the contrast between them and Drake's first steam-driven rig in 1859 or the first crude rotary operation at Spindletop, Texas, in 1901. Steel derricks tower 122ft. to 178 feet. Every step of raising the bit, unscrewing and screwing up again the Iengths of steel tubing joined for a mile or more, is under control from the derrick floor.

On the derrick floor is an array of instruments resembling the instrument board of a power plant or of an aeroplane. A gyro scope compass determines whether the hole is being bored straight. Before its use there were cases of crooked holes drifting many hundreds of feet from the point vertically under the well site. Crooked holes meant trouble, delay, often loss of the well. An ingenious camera also is put to the same use as the gyroscope, taking photographs in the darkness far down in the well. It is the only eye the production engineer has for seeing where he is travel ling. Another instrument is the weight indicator, which shows the weight on the bit. The driller always watches it carefully, for it was found that there is some relation between the weight on the bit and the deflection of the hole, and that the deflection could be reduced by permitting less weight to rest on the bit when drilling. At frequent intervals the engineer in charge of the drilling operation consults charts of recordings from these various instruments.

In every modern operation similar contrasts from the old days are noted, whether the field be steam, Diesel, or electrically drilled. Improved devices for core drilling make it possible to obtain, for laboratory study, complete sections of the rocks and sands pene trated. In rotary drilling intensive studies of drilling fluids have resulted in compounds that greatly aid in the control of wells and the prevention of blow-outs. Methods of completing wells are greatly improved. It is important, in modern practice, to conserve gas pressure in an underground reservoir. Cementing methods are applied that seal off the gas sands underlying oil sands, so to con serve gas pressure. It is important also to case or cement off encroaching water from penetrated strata. Effective methods are applied to prevent water flooding by use of casing perforation, opposite oil zones only, leaving water zones cemented off. The major units for drilling—derricks, boilers, and pumps—are all of much heavier design. All tubular goods and drilling tools have reached a standard of strength and reliability consistent with the demands made upon them for deeper drilling. Failure of equip ment, once a common occurrence, is rare. Wells may be drilled safely to depths exceeding 1 o,000f t., not as an unusual, but as an every-day occurrence.

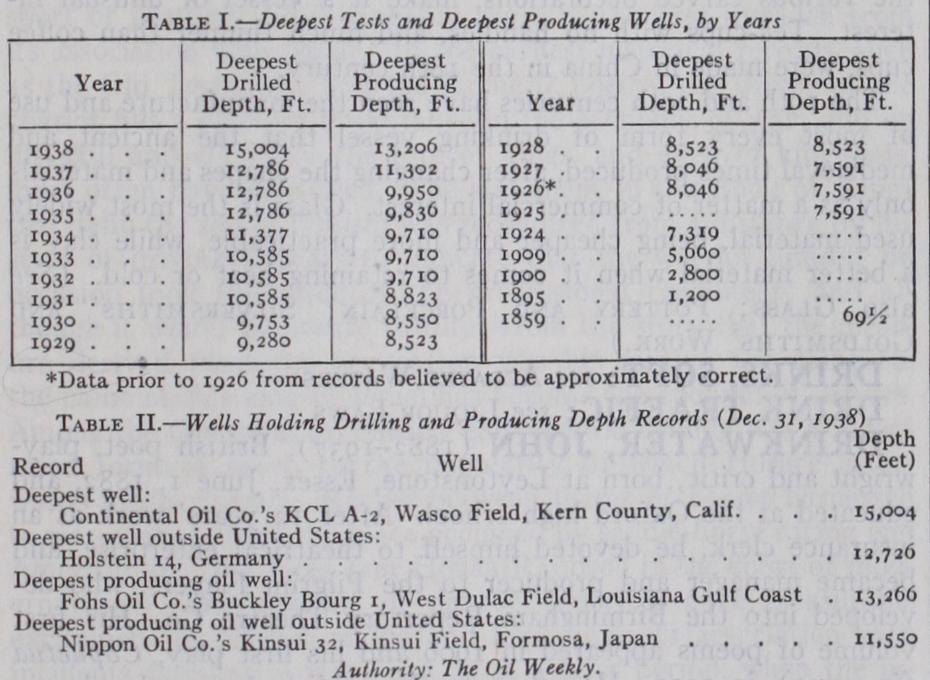

As compared with io or 15 years before, well depths commer cially reached in 1938 more than doubled. See Table I.