Portable Dwellings

PORTABLE DWELLINGS Tents.—People who are constantly shifting camp, whether wan dering hunters in pursuit of game or nomadic herdsmen moving their flocks to pasture, have invented portable dwellings, varying from the flimsy skin tent of the Eskimo, or the equally skimpy tent of the guanaco area of South America, to the luxurious and spacious yurt of the rich steppe lands of Asia. The Eskimo tent, the common summer residence from Alaska to Labrador, is found also in Siberia, and is perhaps linked on to the cloth-covered tent of the reindeer Lapps in Scandinavia. South of the Eskimo area the typical tipi (its Dakota name) is found from northern New England throughout the Cree and Ojibway (Chippewa) country and across the bison area to north-west Canada. The nucleus is a tripod of poles against which other poles are propped, and over this is stretched a cone-shaped cover of stitched skins, pegged out all round. A skin curtain hangs across the entrance, which faces the rising sun, and poles on the outside regulate smoke flaps on either side of the hole at the top (Pl. fig. 2). In wooded areas where birches grow, sheets of bark are used as coverings, but skins are more suitable for transport. This is the ideal dwelling of no madic peoples, easy to set up, easy to take down, easy to shift. The poles, tied on either side of dog or horse, drag along the ground, the cover wraps the scanty household gear in a bundle and lies across their trailing ends. The Ostiak choom in the lower Obi dis trict is made of 20 or 3o thin poles fixed in a circle and fastened together at the top, covered with sheets of birch bark boiled to make them pliant, and cut with convex curves to fit over the cone shape of the framework. Extra skins may be added outside with an opening to leeward. The most luxurious tents in all Asia are those of the rich steppe lands of the centre, from the Khalka in eastern Mongolia to the Khirgiz nearing the Urals in the west. In this mainly treeless area long tent poles are not easily found, and the foundation is made of latticework hurdles (usually willow) lashed to posts firmly fixed in the ground. From these, smaller poles radiate towards the centre. Over this framework are stretched the covers of skins or felt, threefold in winter to mitigate the intense cold. There is a hole in the centre of the roof, through which the smoke from the fire of argol or cattle dung can escape, though it is usually kept closed by a piece of felt drawn across by a string. A felt curtain, often beautifully embroidered, falls over the entrance facing south, and curtains fastened to the sides of the tent can be let down to form separate compartments. This form of tent is heavy and cumbersome, but camels, horses and cattle provide abundant beasts of burden, and the setting up and taking down of the tent is always woman's work.

A far simpler tent suffices for the hardy desert herdsmen of western Asia and north Africa. The typical Bedouin tent is of sticks, sometimes forked with a ridge-pole, which irregularly supports a cover made of woven goats' hair strips sewn together, usually black from use if not by nature. The cover may be pegged down at the back or banked up with stones and sand, but it is an awning rather than a tent.

Long Houses.

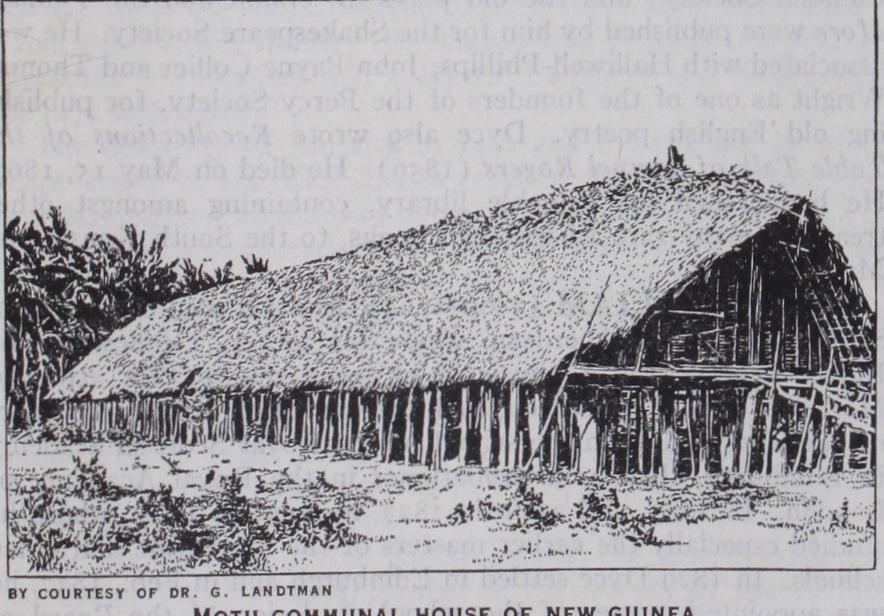

A great stimulus is given to house building in those primitive societies in which the house belongs not to the individual but to the clan; or where there are secret societies or men's club-houses; or where it is the custom for the unmarried men or the warrior class to sleep in a separate house. These cus toms lead to the building of houses such as the long houses of British Columbia ; the circular houses on the Putumayo, 7oft. in diameter, holding 7o families under one roof ; the long houses built of piles along the river banks in Borneo, containing 4o to 5o fam ilies; the Kiwai houses, on piles, off the New Guinea coast, two or three hundred feet long, holding 18o people (fig. 5) ; and the men's club-houses that are a conspicuous feature of Melanesian villages generally. The best of the long houses in Borneo are built by the Kayan. The piles are massive posts of iron-wood, 2 5f t. to 3of t. high, supporting a ridge-pole roof. The floor is laid on piles 7 f t. or 8ft. high, with cross beams mortised to these and large planks laid across, running the length of the house. The side furthest from the river is walled in, forming separate rooms, but on the river side is a long gallery, protected by the overhanging roof. This is the sleeping place for bachelors and male visitors and the place for receiving guests and carrying on the daily work, such as padi husking, etc. The floors of the inner rooms are of split bamboo, placed a little way apart like latticework, so that all rubbish falls to the ground underneath. The pigs live under the house, and this also serves as a place for storing boats. Entrance to the house is by a notched pole at one end of the verandah.