Synthetic Dyes

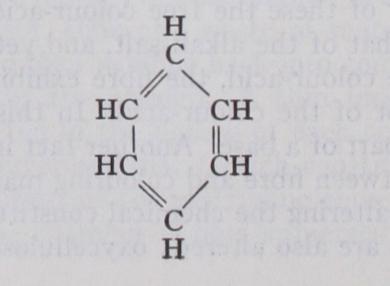

DYES, SYNTHETIC. Synthetic or artificial dye-stuffs, also known as coal-tar dye-stuffs, artificial colouring matters, ani line dyes, like those of natural origin, are complex compounds of carbon in association with other elements, more especially with hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen or sulphur. They belong to the class of organic substances included in the aromatic division (see CHEMISTRY : Organic). Like "aromatic" compounds in general, dyes have their constituent carbon atoms arranged in the form of closed chains. They may be regarded as derived from "closed chain" or "benzenoid" hydro-carbons by the replacement of cer tain of the hydrogen atoms by atomic groups of other elements. Thus the hydro-carbon benzene or benzol, has the structure :— which, for the sake of simplicity, is usually abbreviated to a plain hexagon. The replacement of certain of the hydrogen atoms in this colourless benzene by suitable atomic groups gives rise to dye-stuffs; and these dye-stuffs may contain a single benzene nucleus, or more frequently are constituted of two or more such benzene nuclei united by certain of the atomic groups introduced. Furthermore, the hydro-carbon nuclei which are thus bound to gether to form a more complex molecule, may be those of the same or of different hydro-carbons. In other words, we may regard the dye-stuff molecule as consisting of one or more chains of carbon atoms, which form the skeleton of the system, and to which are attached various other groups of atoms. Upon the structure and position of the latter groups the character and properties of the dye-stuff (colour, fastness, etc.) mainly depend.

Raw Materials.

Nearly all the synthetic dyes are derived from one or other of the five hydrocarbons, benzene, toluene, xylene, naphthalene and anthracene. The most convenient source of these hydrocarbons is coal-tar, obtained in the high temperature carbonization of coal for the manufacture of illuminating gas or of metallurgical coke. The more volatile hydrocarbons, benzene and toluene, are contained also in considerable quantities in the gas produced in these operations and can be extracted therefrom by washing or "scrubbing" the gas with high-boiling solvents. In addition to the hydrocarbons mentioned above, coal-tar contains a large number of other substances, bases, phenols, and more complex hydrocarbons, most of which find no application in dye stuff manufacture.The separation of the useful hydrocarbons from the other com pounds present in coal-tar and from each other, is effected by making use of the differences in their boiling-points and other physical and chemical properties. Upon submitting coal-tar to distillation, which is carried out in very large wrought-iron stills containing many tons, the first portion of the distillate contains benzene and methyl-benzenes. This is followed by a fraction rich in the hydrocarbon naphthalene, and finally a high-boiling oil containing anthracene passes over. The two latter substances being solids crystallize out from the oils upon cooling and are separated by filtration. The raw hydrocarbons thus obtained are purified by submitting them to distillation or recrystallization, and also to chemical washing with acids and alkalis. When finally purified benzene, toluene, and xylene are colourless volatile liquids whilst naphthalene and anthracene are colourless solids.

Intermediates.

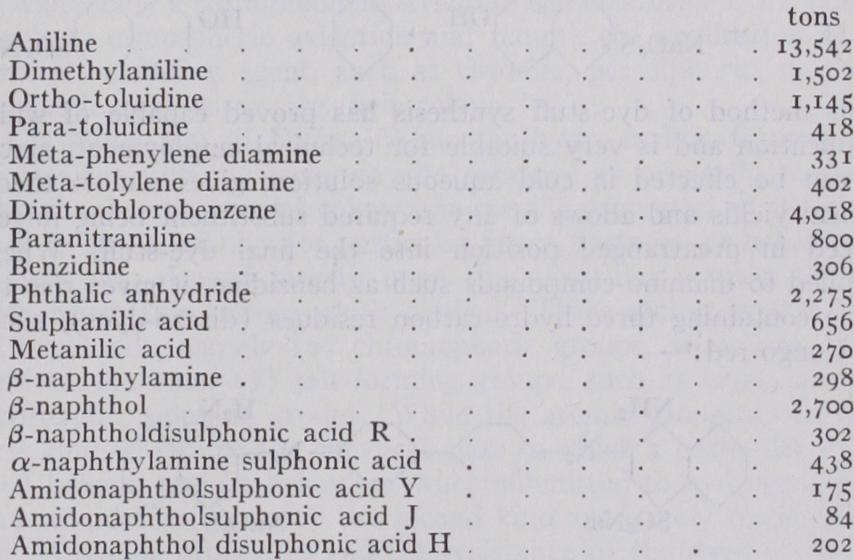

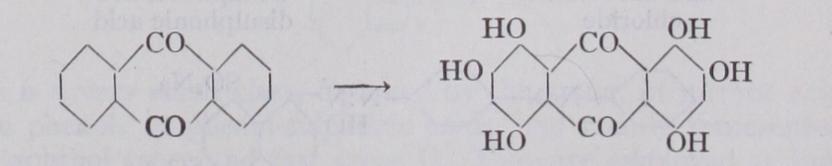

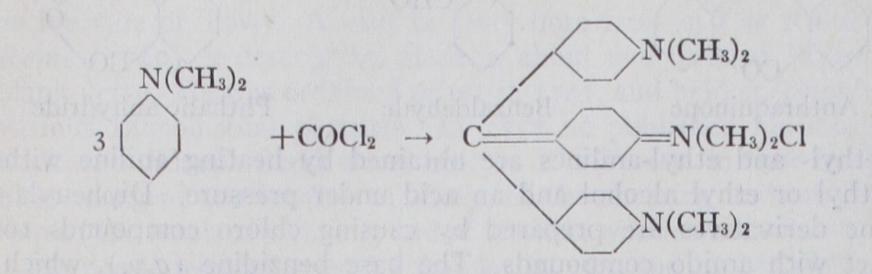

With these hydr. carbons as starting mate rials the various dyestuffs are built up in successive stages. In the first place the hydrocarbons are converted into so-called "inter mediate products," which are obtained by replacing one or more atoms of hydrogen attached to the carbon nucleus by simple atomic groups such as the amido group the dimethylamido group the hydroxy group OH, the sulphonic group etc. Only a few illustrations can be given. Thus from benzene there is prepared by treatment with nitric acid, nitro benzene, and from this by reduction (hydrogenation) aniline:— From naphthalene there is prepared by the action of sulphuric acid the a and (3-sulphonic acids, which upon fusion with caustic soda give a and (3-naphthols :— By the action of nitric acid upon naphthalene, nitronaphthalene is obtained, which upon reduction gives a-naphthylamine. On the other hand f3-naphthylamine is obtained by heating 13-naphthol with ammonia and sodium bisulphite under pressure. Again, from the hydrocarbon anthracene there is obtained by oxidation. anthra quinone, a very important intermediate for fast dyestuffs; whilst by oxidation of toluene there is produced benzaldehyde, and of naphthalene, phthalic anhydride:— Methyl- and ethyl-anilines are obtained by heating aniline with methyl or ethyl alcohol and an acid under pressure. Diphenyla mine derivatives are prepared by causing chloro compounds to react with amido compounds. The base benzidine (q.v.), which is an important intermediate for direct dyeing cotton colouring matters, is obtained by a molecular transposition from hydrazo benzene under the influence of acids, this substance itself being prepared by alkaline hydrogenation of nitrobenzene :— By applying these and similar chemical treatments, and thus introducing two or more of such atomic groups, either of the same or of different kinds, into the hydrocarbon nucleus, there are obtained a great variety of intermediate compounds,—diamines, dihydroxy compounds, amidophenols, naphthol sulphonic acids, naphthylamine sulphonic acids, amidonaphthols, amidonaphthol sulphonic acids, etc. In these compounds isomerism plays an important role, since the position occupied by the respective groups in reference to the carbon skeleton is a factor of great importance in determining the properties of the colouring-matter finally resulting.The commercial importance of some of these intermediates is illustrated by the following production figures for the year 1927 published by the Tariff Commission of the United States (the only country for which statistics are at present available) :— Dye Synthesis.—The above intermediate products are for the most part colourless bodies like the hydro-carbons from which they are derived. They are convertible into dye-stuffs when, by further chemical treatment, a greater complexity of molecular structure is obtained. This may be effected, (I) by the introduc tion of further substituent groups, or (2) by the linking together of the molecules of two or more intermediate compounds into a larger molecule. An example of the first kind is the formation of the yellow dye-stuff picric acid (2 :4 : 6-trinitro-phenol) by the nitration of colourless phenol (see CARBOLIC ACID). Another case in point is the conversion of the nearly colourless anthraquinone into the dark blue hexahydroxyanthraquinone (alizarine hexacya nine) by the introduction of six hydroxyl groups :— The synthesis of dye-stuffs by the linking together (chemically termed "condensation") of simpler molecules is employed in a great number of cases. Thus crystal violet is obtained by the con densation of three molecules of dimethyl-aniline by means of a molecule of phosgene gas :— water and hydrochloric acid being also formed in the reaction. This crystal violet is a hexamethyl derivative of pararosaniline. The pentamethyl derivative comprising the chief constituent of methyl violet is made from dimethylaniline, phenol and salt in presence of cupric chloride by the oxidizing action of air.

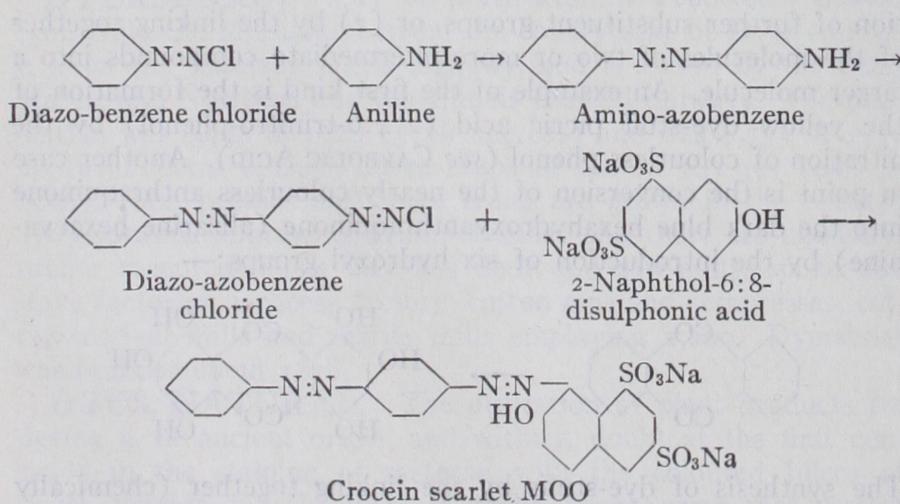

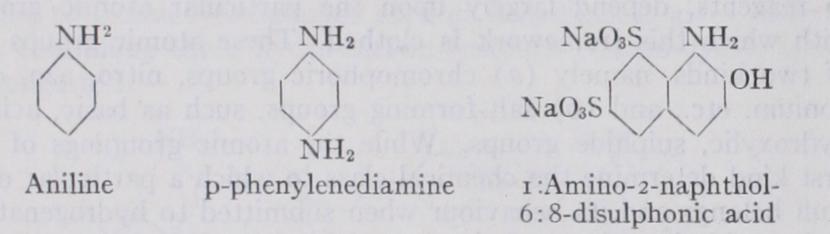

The Diazo-reaction.—The most largely used of all methods of dye-stuff synthesis is the diazo-reaction (P. Griess, 1864), by which the very large class of compounds known as azo-dyes are ob tained. The procedure depends upon the fact that almost all primary amino-derivatives of aromatic hydrocarbons, when treated in acid aqueous solution with nitrous acid are converted into diazonium salts. These latter are for the most part colour less compounds of great instability and extremely reactive. When brought in contact with hydroxy or amino-derivatives of aromatic hydro-carbons they "couple" with the latter giving rise to com pounds in which the two hydro-carbon residues are united by a double nitrogen group (azo group). For example, when benzene diazonium chloride or diazo-benzene chloride, derived from aniline hydrochloride, is mixed with an alkaline solution containing, e.g., the sodium salt of Schaeffer's acid (2-naphthol-6-sulphonic acid), a bright orange dye-stuff (crocein orange) is at once produced :— use of the fact that certain phenols and aminophenols are capable of coupling with more than one molecule of a diazo-compound, azo-dyes can be built up containing three, four or more azo groups, and a correspondingly increased number of hydro-carbon residues. With growing molecular complexity, the colour of the dye-stuff obtained increases in depth, especially when naphthalene residues are introduced into the reaction. The diazo-reaction can be applied not only for producing dye-stuffs in substance but also for their synthesis within or upon textile fibres, whereby colours can be obtained. Thus when cotton which has been impregnated with an alkaline solution of /3-naphthol is passed through a cold solution of diazotized p-nitroaniline, the bright scarlet "para red" is immediately produced and remains fixed on the cotton.

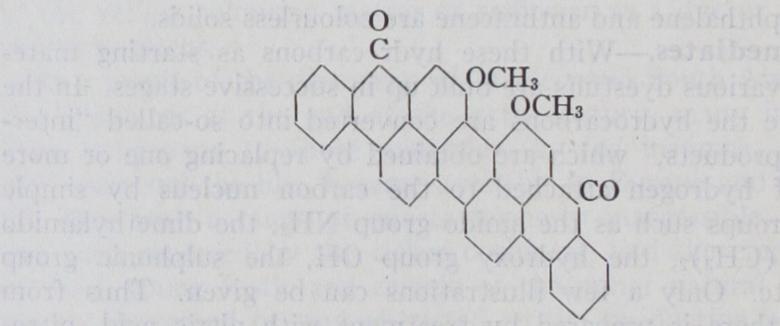

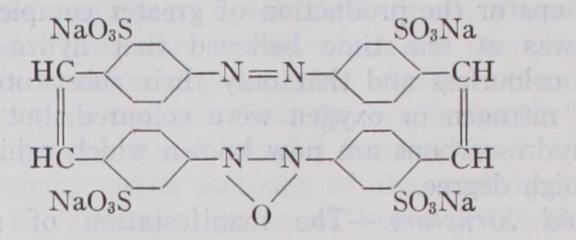

Among the many other methods of dye-stuff synthesis, de pendent upon the linking together of hydro-carbon nuclei into more complex molecules, may be mentioned the production of synthetic indigo. The raw materials in this case are aniline and chloro-acetic acid, which upon condensation give phenylglycine. This, upon fusion with caustic alkali, produces indoxyl and by air oxidation indigo :— The most complex molecular structures are those possessed by the vat dyes of the anthraquinone class. These are obtained by the linking together of two or more anthraquinone residues or by the fusion of these residues with other groups in such a way as to produce new carbon rings. The very fast indanthrene blue RS or duranthrene blue is obtained by heating (3-aminoanthra quinone with caustic alkalis and subsequent oxidation by air. The change is thus represented :— This method of dye-stuff synthesis has proved capable of wide application and is very suitable for technical employment, since it can be effected in cold aqueous solution, gives almost theo retical yields and allows of any required substituent being intro duced in prearranged position into the final dye-stuff. When applied to diamino-compounds such as benzidine, it gives rise to dyes containing three hydro-carbon residues (disazo-dyes), such as Congo red :— Disazo-dye-stuffs of another type are obtained by coupling diazo compounds with primary monoamino-derivatives, again diazo tizing the free amino-groups in these products and recoupling the diazo-compounds with suitable hydroxy or amino-derivatives. For example :— i3y applying a similar process to diamines, and also by making A still more complex example is the dye-stuff caledon jade green which has the structure :— It is obtained from anthraquinone, by first condensing with gly cerine, then fusing with caustic soda, oxidizing the product (dibenzanthrone), and finally introducing methyl groups in place of two hydrogen atoms. While initially all the alizarine or anthra quinone dyes were synthesized from anthracene, recently with the cheapening of phthalic anhydride, these dyes are also made by condensation of phthalic anhydride with benzene or its derivatives.

In the United States of America practically all of the anthra quinone dyes are made from phthalic anhydride, and not from anthracene. It will be seen from the examples given that it is possible for the colour chemist to build up dye-stuff molecules having almost any required structure and containing the particular atomic groupings which are known to produce the desired proper ties. Details of manufacture are given in the books in the bibli ography appended.

Colour and Chemical Constitution.

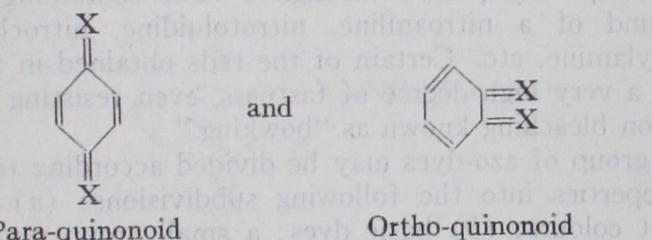

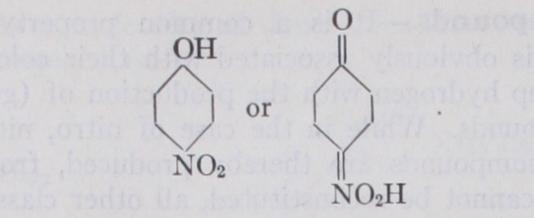

The cause of colour in organic compounds is still not fully explained. Most deeply coloured compounds, whether organic or inorganic, exhibit a condition which may be described as unsaturation; i.e., a tendency to take up hydrogen or to pass from a higher to a lower stage of oxidation, accompanied by a disappearance of the colour. In the compounds of carbon, colour is only present in those having a chain of atoms which are not fully saturated. In the simpler hydrocarbons of the aromatic series, in which this condition exists, colour is not apparent to the eye. Nevertheless, these substances exert a large degree of selective absorption of light in non-visible regions of the spectrum (the ultra-violet). To bring this absorption within the visible portion of the spectrum requires the introduction into the molecule of other atomic groups or the production of greater complexity of struc ture. It was at one time believed that hydro-carbons were invariably colourless and that only their substituted derivatives containing nitrogen or oxygen were coloured, but a number of complex hydro-carbons are now known which exhibit this prop erty to a high degree.Quinonoid Structure.—The manifestation of strong colour and dyeing properties amongst aromatic compounds is very fre quently found associated with a quinonoid structure; i.e., with a peculiar unsaturated condition of the hydro-carbon ring similar to that occurring in the quinones. Some chemists, in fact, have gone so far as to assert that all dye-stuffs have a quinonoid structure, or are capable of existence in a quinonoid state. The two quinones derived from benzene have the structure:— while those derived from naphthalene have the structure:— Dyestuffs having a quinonoid structure may be represented there fore upon the general types :— or by similar formulae derived from naphthoquinone or anthra quinone. In these formulae the symbol X may stand for various simple or complex atomic groups. Thus in the formula of crystal violet, already mentioned, the central benzene nucleus, is quinonoid, and this, or a similar group, is regarded as the source of colour in all the dye-stuffs of the carbonium or tri phenylmethane class. It may therefore be termed the chromophor (colour-giver) of this class of dye-stuffs.

Some dye-stuffs are capable of existence both in a quinonoid and a benzenoid (non-quinonoid) form, and may change from one to the other with alteration of conditions (acidity, alka linity, temperature, solvent, etc.). This transformation is ac companied by a loss or gain of colour. A familiar example is the change of the colourless phenolphthalein (q.v.) to its deep red alkaline salts, and the loss of colour of the latter when rendered acid. Such changes probably have an important bearing upon the want of fastness of certain dye-stuffs to light, soap and other agencies, especially in the carbonium class.

Leuco-compounds.

It is a common property of all dye stuffs, which is obviously associated with their colour, that they readily take up hydrogen with the production of (generally) col ourless compounds. While in the case of nitro, nitroso and azo dyes, amino-compounds are thereby produced, from which the original dyes cannot be reconstituted, all other classes of colour ing-matters are converted with greater or lesser ease into so called leuco-compounds. These leuco-compounds contain two atoms of hydrogen more than the original dye from which they are formed, and are reconvertible into the latter upon oxidation. The above facts receive a ready explanation from the quinonoid hy pothesis and may be represented by the general expression :— In other words, the reduction (hydrogenation) of dye-stuffs, as of their prototypes the quinones, gives rise to more saturated ben zenoid compounds. In the case of the dyes of the indigo and an thraquinone groups alone, are the leuco-compounds coloured, these exceptions being probably referable to the presence in the dye of two chromophoric groups, only one of which is hydro genated so that the leuco-compound is still quinonoid.The facility with which the leuco-compounds derived from dye stuffs of various classes are reoxidized to the original dye-stuffs varies with the structure, and is probably dependent upon whether the dye-stuff has an ortho-quinonoid or a para-quinonoid config uration. The leuco-compounds of indigo dyes, which must have an orthoquinonoid constitution, are readily oxidized by air, while those of the triphenylmethane, indophenol and indamine classes, to which only a paraquinonoid structure can be ascribed, are fairly stable to atmospheric oxidation and require the application of a stronger oxidizing agent, such as chromic, persulphuric, or per manganic acid, to restore their colour.

Classification of Dyes.

While the hydro-carbon framework of the dye-stuff molecule may be regarded as primarily respon sible for the existence of colour, the specific properties of the dye, such as shade, affinity for particular fibres, fastness, or behaviour to reagents, depend largely upon the particular atomic groups with which this framework is clothed. These atomic groups are of two kinds, namely (a) chromophoric groups, nitro, azo, car bonium, etc., and (b) salt-forming groups, such as basic, acidic, hydroxylic, sulphide groups. While the atomic groupings of the first kind determine the chemical class to which a particular dye stuff belongs and its behaviour when submitted to hydrogenation and reoxidation, those of the second kind are largely responsible for its dyeing properties and the resistance of the dyed material towards soap, alkalis, acids, milling, light, etc. A dye-stuff mole cule of almost any class may be given basic, acidic, or mordant fixing properties by the introduction of amino or N(CH3)2], sulphonic (HS03), or hydroxyl (OH), groups respectively in suitable positions. Dye-stuffs are therefore classified in two ways, that is (a) in chemical classes dependent on the specific chromophor present, and (b) in dyeing classes according to dye ing properties and affinity for particular fibres.

Chemical Classes.

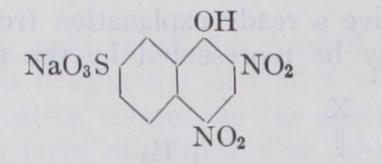

The following are the most important classes of dye-stuffs arranged according to their constituent chro mophoric groupings : I. Nitroso-compounds.----Typical grouping:— This is a very small class, obtained by the action of nitrous acid upon phenols or phenol-sulphonic acids, and mainly represented by naphthol green and fast green 0. They are employed as iron lakes, the nitroso-group having the property of forming stable compounds with heavy metallic oxides.II. Nitro-compounds.—Typical grouping :— This is also a small class, consisting of yellow acidic dyes, such as martius yellow and naphthol yellow S. The latter has the constitution:— and is obtained by the action of nitric acid upon nitroso-i naphthol-2 : 7 -disulphonic acid. Picric acid, no longer used as a dye but as an explosive, also belongs to this class.

III. Azo-compounds.—Typical grouping :— R — N : N — R, in Iii. Azo-compounds.—Typical grouping :— R — N : N — R, in which R stands for hydro-carbon residues of the benzene or naphthalene series. This is a very large class of dye-stuffs with over Soo members in general use. The annual production in the United States (for which country alone statistics are available) is approximately 13,5oo tons, valued at over $I s,000,000 (L3,000, 000). The azo-compounds comprise members of nearly every shade and exhibit a great variety of properties according to struc ture and the auxiliary atomic groupings present. The azo (N2) group may be present in the molecule once, twice, three or more times, the number of hydro-carbon nuclei thus linked increasing with the number of azo-groups. The simpler azo-dyes are usually yellow to red, those of more complex structure, especially when containing naphthalene nuclei, violet, blue or black. Lake forma tion also leads to a deepening of the colour; thus the red chromo tropes, containing only one azo-group, become dark blue upon con version into chromium lakes. Under the action of reducing agents such as sodium hydrosulphite, stannous chloride or zinc dust, the azo-dyes are split up into two or more colourless amino-corn pounds, each N2 group being severed between the two nitrogen atoms. Thus crocein scarlet, MOO, the structure of which has already been given, yields upon boiling with zinc dust and ammonia the following three products:— By separating and identifying the products of reduction, the struc ture of the azo-dye may be inferred, and this procedure has be come a valuable method of examination and analysis. When the constitution of the dye-stuff is known, the determination of the amount of hydrogen consumed during its reduction, best ascer tained by titration with a standard solution of titanious chloride, serves as a convenient and accurate method for the quantitative estimation of the dye either in substance or upon textile fibres.

The property possessed by azo-dyestuffs of being resolved by hydrogenating agents into colourless components is also of value to the calico printer. In the production of so-called "discharge" or "foulard" styles, cotton or silk materials which have been dyed dark blue or other shades with appropriate azo-dyes, are printed with thickened reducing agents. Upon steaming the material the azo-colour is discharged leaving a white pattern upon a coloured ground. Certain azo-dyestuffs contain, in addition to the group, a second chromophore. Upon reduction, such dyes give the parent amino-compound, for example indoin blue gives safranine, while primuline red gives the yellow primuline. Oxidizing agents also effect a splitting of azo-dyes into two or more products, but in this case the division does not occur between the two nitrogen atoms, for the azo-group is left intact as a diazonium group at tached to one of the hydro-carbon residues. By the action of strong nitric acid upon para red, nitro-diazobenzene nitrate and nitro43-naphthol are obtained.

A special class of dye-stuffs containing the azo-group but ob tained without the employment of the diazo-reaction, by the in tra-molecular rearrangement of p-nitro-toluene-o-sulphonic acid, is the stilbene series. When p-nitro-toluene-o-sulphonic acid is submitted to the action of aqueous caustic soda, a yellow dye-stuff, direct yellow R, is formed, having the constitution :— This yellow compound is the most important member of this series, over 200 tons valued at $200,000 (L4o,000) being sold annually in the United States alone. Upon alkaline reduction it gives rise to other members of this group. The dye-stuffs of the stilbene series dye cotton directly and exhibit a greater fastness to light than other azo-dyes. They also behave differently with reducing agents, for instead of being at once split into colourless components they give at first hydrazo-compounds which are readily reoxidized to the stilbene dye-stuff.

Azo-dyes which do not contain a salt-forming group, acidic or basic, are insoluble in water and therefore cannot be used in ordinary dyeing operations. They are employed as pigment colours (ground with mineral materials), and for colouring oils, waxes and varnishes. Certain of them also find a large and increas ing application as colours produced on, or within, the fibre itself, and which on account of their insolubility are very resistant to washing, bleaching and light. The typical example of this class is para red, to which reference has already been made. This method of dyeing has been greatly extended by the introduction of the so-called azoic series, in which the cotton is impregnated with an anilide of j3 -oxynaphthoic acid (known commercially as a "naphthol AS" compound), such as and subsequently passed through a bath containing the diazo compound of a nitroaniline, nitrotoluidine, nitrochloroaniline, naphthylamine, etc. Certain of the reds obtained in this manner exhibit a very high degree of fastness, even resisting the process of cotton bleaching known as "bowking." The group of azo-dyes may be divided according to their dye ing properties into the following subdivisions: (a) Neutral or pigment colours; (b) basic dyes: a small group represented by chrysoidine, Bismark brown, and a few other products; (c) acidic dyes: a large group to which the ordinary wool yellows, oranges, scarlets and blacks belong; (d) mordant dyes or chrome dyes: used in dyeing fast colours on wool or in cotton printing; (e ) direct substantive or salt dyes: a large group of colouring-matters which have an affinity for cotton and other cellulose fibres; (f) acetate silk dyes (ionamines, S.R.A. colours, etc.) : a class of recent introduction, dyeing acetyl-cellulose ("Celanese," etc.), but having no affinity for cotton, linen, or viscose silk; (g) spirit soluble dyes : employed in the colouring of stains, varnishes, waxes and gasolene (petrol) .

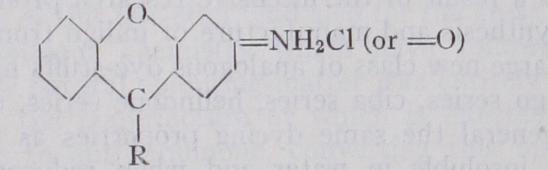

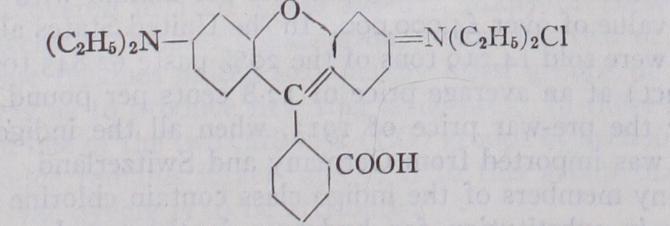

IV. Carbonium or Triphenylmethane Compounds.—Character istic grouping :— in which R' and R" may both represent benzene nuclei or R' may be a benzene nucleus and R" a naphthalene nucleus. Crystal and methyl violet, the constitutions of which have been given already, are typical members of this class. In the United States in 1926 over i,000 tons of the carbonium dyes were sold for over $3,0o0,0ov (f 600,000) .

The carbonium dye-stuffs are characterized by very brilliant and intense shades of red, violet, blue and green. They have basic, acidic, or mordant fixing properties, according to the auxiliary grouping they contain. As a class they are rather deficient in fastness to light, and frequently also in fastness to washing and alkalis, by which they are partially decolourized. This loss of colour, especially noticeable in the case of the alkali and soluble blues, is attributed to a change of type from a quinonoid to a car binol structure. It is diminished by the introduction of a chlorine atom or a sulphonic or other group into one of the benzene nuclei in a contiguous (ortho) position to the central carbon atom. Seto glaucine, patent blues, erioglaucines, xylene blues and some of the acid violets possess such a structure and exhibit a degree of fastness to washing superior to that of the other members of the class. The basic dyes of the carbonium series are represented by magenta, methyl violet, crystal violet, malachite green, brilliant green, setoglaucine, setocyanine, and the Victoria blues. The acidic members comprise acid magenta, alkali and soluble blues, acid greens, acid violets, patent blues, erioglaucines, xylene blues, etc. The mordant-fixing members are known as eriochrome azurols and eriochrome cyanines, their mordant-fixing property being due to the presence of a carboxyl group in the molecule.

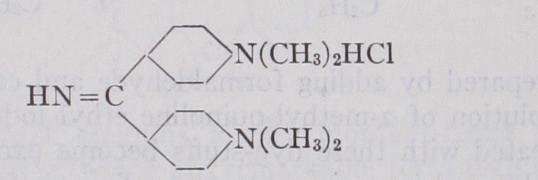

The bright yellow basic dye, auramine, which has the consti tution : should also be classed as a carbonium compound, though it has but two benzene nuclei. The basic carbonium dyes have pow erful toxic and antiseptic properties; thus auramine is employed in surgery, especially in operations upon the eye. It appears prob able that derivatives of these dyes containing "labile-acidic" groups such as the sulphato-group which can be split off in the organism, may find application in internal medicine. It has also been observed that the leuco-derivatives of the car bonium dyes, which are far less toxic than the dye-stuffs them selves, exert a powerful neutralizing effect upon certain disease toxins such as those of diphtheria and tetanus.

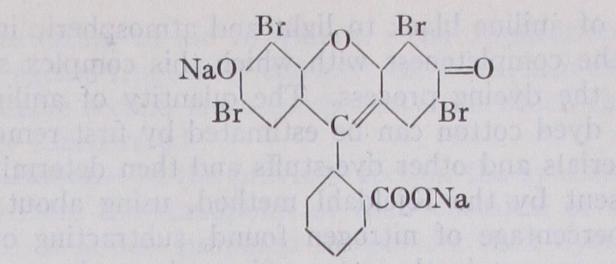

V. Xanthene, Pyrone or PljHzalein Class. — Characteristic grouping :— This class, consisting partly of basic and partly of acidic and a few mordant-fixing members, comprises some of the most bril liant dye-stuffs available to the colour user. In the United States the consumption during 1926 was over 250 tons valued at over $700,000. They are closely related to the carbonium class, from which they differ by the presence of an oxygen atom linking two of the benzene nuclei, and are less liable than the latter class to undergo conversion into colourless carbinol forms, and hence are faster to alkalis, soap and milling. The basic members of this class are known as rhodamines, the B brand of which has the structure : and is obtained by condensing phthalic anhydride with m-diethyl amino-phenol. The acid rhodamines and fast acid violets are sulphonic acids of the basic dyes. The eosines are weakly acidic and have a phenolic structure, for example eosine A:— The eosines are capable of forming unstable metallic lakes and their lead salts are employed for the preparation of bright red pigments ("vermillionettes") used in poster printing. The unbro minated compound, fluorescein (q.v.), has a yellow colour and in alkaline solution an intense green fluorescence, which is ap parent at extreme dilutions and has led to the dye-stuff being employed for tracing the course of underground streams and the contamination of water supplies by drainage.

In their behaviour towards reducing agents, the xanthene colours are distinguished from the carbonium class by a greater resistance to decolourization, and a somewhat greater oxidizability of their leuco-derivatives. In this respect they occupy an inter mediate position between the para- and the ortho-quinonoid classes of dye-stuffs. The eosines and rhodamines, when not containing sulphonic acid groups, are taken up from aqueous solution by ether, the former from an acid medium, the latter from an alka line or neutral medium. The sulphonated (acidic) members of both classes are entirely insoluble in ether. The eosines, being brominated or iodinated compounds, are further characterized by the liberation of the respective halogen when heated with sulphuric acid and manganese dioxide.

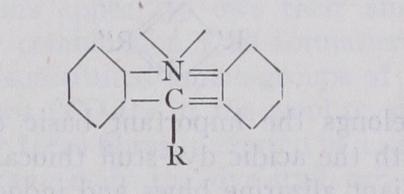

VI. Acridine Class.—Characteristic grouping:— This is a small class of yellow and orange dyes containing basic members only, which find their main application in leather dyeing, calico printing and medicine. The chief representatives are phos phine, acridine yellow, acridine orange, benzoflavine and rheonine. Acriflavine (see AcRmINE) has obtained considerable importance in surgery as a local antiseptic, but is not employed in dyeing. The Acridine dye-stuffs are somewhat resistant to reduction and are therefore not easily decolourized by hydrosulphite.

VII. Azine Class.—Characteristic grouping :—Vii. Azine Class.—Characteristic grouping :— This class contains both basic and acidic dye-stuffs, ranging in shade from red to blue. While the basic members are represented by the red safranines and by the blue to black spirit-soluble indu lines and spirit-soluble nigrosines, the acidic members comprise the rosindulines, water-soluble nigrosines, water-soluble indulines, indocyanines, acid cyanines, etc. Closely related to safranine is Perkin's mauve, the earliest coal-tar dye-stuff. The indulines and nigrosines find their chief application in the colouring of leathers, oils and waxes (boot polishes, printing inks and lacquers), and more than Boo tons are sold annually in the United States alone.

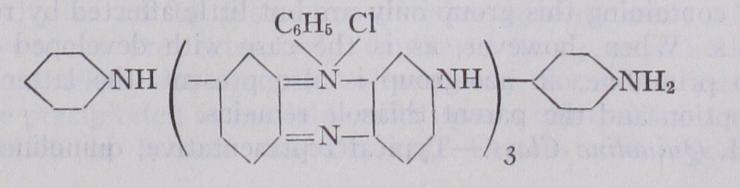

Aniline black is an insoluble dye, which is produced on the cotton fibre by impregnation of the latter with salts of aniline and subsequent oxidation with chlorates, dichromates, etc. It is largely employed in the dyeing of cotton cloth and in calico printing. The colouring-matter is a very complex azine containing eleven ben zene nuclei and probably represented by the following formula :- The fastness of aniline black to light and atmospheric influences depends on the completeness with which this complex structure is formed in the dyeing process. The quantity of aniline black present upon dyed cotton can be estimated by first removing all finishing materials and other dye-stuffs and then determining the nitrogen present by the Kjeldahl method, using about 5 g. of cloth. The percentage of nitrogen found, subtracting o• r % for that normally present in the cotton fibre, gives when multiplied by the factor 6.6 the percentage of aniline black.

VIII. Oxazine Class.—Characteristic grouping :Viii. Oxazine Class.—Characteristic grouping :- in which R' is a benzene nucleus and R" a benzene or naphthalene nucleus. This class comprises the basic dyes, Meldola's blue, nile blue, capri blue, and cresyl blue; also the basic-mordant dyes, gallocyanines, gallamine blue, celestine blue, prune, delphine blue, modern violets, modern cyanines, anthracyanines, chromazurines, etc. The dyes of the latter category possess both "basic" and "mordant-fixing" properties and are employed in calico printing. Gallocyanine has the following structure :— To this class belongs the important basic dye-stuff, methylene blue together with the acidic dye-stuff thiocarmine, the mordant fixing dyes, brilliant alizarine blues and indochromine. The thia zine chromophore is probably present also in the blue and black dye-stuffs of the "sulphide" class. The leuco-compounds of this and the two preceding classes are very oxidizable, being readily reoxidized by air into the original dye-stuffs.

X. Tjiiazole Class.—Characteristic grouping :— The most important dye-stuff of this class is the diazotizable dye stuff, primuline, in which the typical thiazole group is present twice :— This colouring-matter dyes cotton directly in primrose-yellow shades, which, owing to the presence of an amino-group, can be diazotized and coupled on the fibre. Thus the largely used primu line red is produced by passing cotton dyed with primuline through an acidified solution of sodium nitrite and afterwards through an alkaline bath of 13 -naphthol. The colours thus obtained are very fast to washing. Other members of the thiazole class which dye cotton directly, though they are not diazotizable, are chloro phenine yellow, Clayton yellow and thioflavine S. Thioflavine T has basic properties and is used in calico printing, giving very pure greenish-yellow shades. In the thiazole class also belong the direct-dyeing reds, erika, geranines, titan pink and diamine rose, which contain an azo-group in addition to the thiazole chromo phore. The thiazole chromophore is difficult to reduce and those dyes containing this group only are but little affected by reducing agents. When, however, as is the case with developed colours from primuline, an azo-group is also present, the latter suffers disruption and the parent thiazole remains.

XI. Quinoline Class.—Typical representative, quinoline yellow spirit-soluble :— This compound is obtained from 2-methyl-quinoline and phthalic anhydride. It is insoluble in water and is only used for colouring varnishes and oils, but its disulphonic acid, quinoline yellow water soluble, is an acidic dye-stuff giving bright greenish-yellow fast-to light shades upon wool and silk.

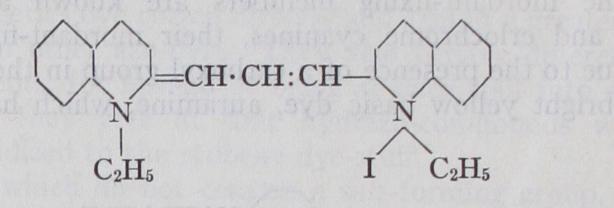

Certain derivatives of the quinoline series, although too fugi tive to be used for dyeing, find a very important application in photography as "sensitizers" in the manufacture of panchromatic or autochrome plates. These dyes are obtained by the action of alkalis on quaternary ammonium derivatives of quinolines and methyl-quinolines, either alone (isocyanines) or in presence of formaldehyde (carbocyanines). Examples of these products are ethyl red, pinaverdole, pinachrome, pinacyanole, kryptocyanine and dicyanine A. Pinacyanole, for example, has the constitution: and is prepared by adding formaldehyde and caustic potash to a boiling solution of 2-methyl-quinoline ethyl iodide. Photographic plates treated with these dye-stuffs become exceedingly sensitive to red light, and in some cases (e.g., dicyanine A) even to infra red rays.

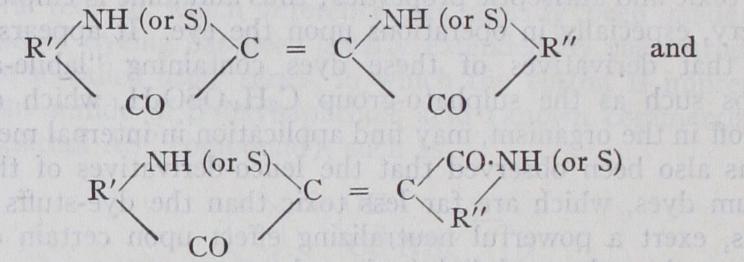

XII. Indigoid Class.—Characteristic groupings:—Xii. Indigoid Class.—Characteristic groupings:— Until 1905, this class of dye-stuffs was represented only by indigo itself, its isomeride indorubin and its sulphonic acid indigo car mine. As a result of the intensive research promoted by the suc cessful synthesis and manufacture of indigo from benzene deriva tives, a large new class of analogous dye-stuffs has become known (thioindigo series, ciba series, helindone series, etc.) . These pos sess in general the same dyeing properties as indigo itself, i.e., they are insoluble in water and when reduced to their leuco compounds they dissolve in alkalis, and from such solutions are absorbed by animal and vegetable fibres; i.e., they are "vat" dyes. Originally obtained by fermentation of the expressed sap of the Indigo/era tinctoria and other similar plants growing in India, Java, etc., indigo is now produced almost entirely artificially by chemical means. This synthesis, which has already been men tioned, ranks with that of alizarine as one of the greatest chemical achievements of the 19th century. The manufacture was com menced about 190o and synthetic indigo has now almost entirely replaced the natural product, the production greatly exceeding that of any other individual dye-stuff and amounting for the world to about 10,000 tons of r 00% product per annum with an approxi mate value of over £4,000,000. In the United States alone in 1926 there were sold 14,219 tons of the paste (2,843 tons of i00% product) at an average price of 12.8 cents per pound, which was below the pre-war price of 1913, when all the indigo consumed there was imported from Germany and Switzerland.

Many members of the indigo class contain chlorine or bromine atoms in substitution for hydrogen in the two benzene nuclei: thus ciba blue 2B is a tetrabromo-derivative of indigo and dyes clearer and brighter shades of blue than the parent dye-stuff.

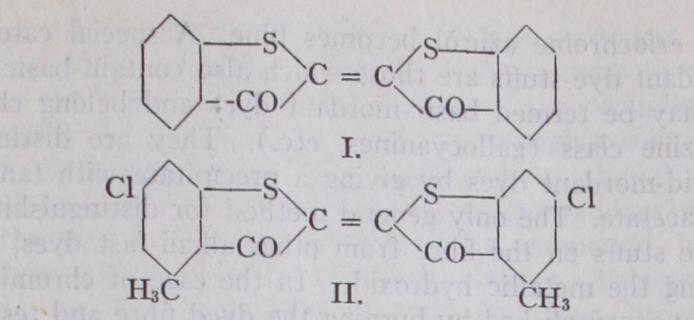

Thioindigo red has the structure I., while helindone pink is represented in II.

Indigo itself and many of its analogues exhibit the unusual property of being volatile at high temperatures and thus of giving coloured vapours on heating. Being more or less neutral in proper ties, the indigoid dyes can be extracted from the animal or vege table fibre by organic solvents such as pyridine or cresol, and extraction by these solvents forms the basis of a convenient method for estimating indigo on wool or cotton materials in the presence of other dye-stuffs. Upon reduction, indigoid dyes give rise to leuco-compounds which have a yellow colour and are readily reoxidized by air to the original dye.

XIII. Anthraquinone Class.—Representative grouping:—Xiii. Anthraquinone Class.—Representative grouping:— This important class contains acidic, mordant-fixing and vat dyeing members, all of which are remarkable for a high degree of fastness to light. The older members, comprising the alizarines, purpurines, alizarine cyanines and alizarine blues, mostly hydroxy derivatives of anthraquinone, are mordant-fixing colouring matters. With aluminium, chromium, or iron hydroxides, they produce fast colours, the shades of which vary with the metallic hydroxide employed. Thus the typical dye-stuff, alizarine, yields with aluminium, a red; with chromium, a maroon; and with iron, a purple. When fixed upon a compound mordant of aluminium, calcium and a fatty acid, the celebrated Turkey red is produced. This colour was originally dyed by means of madder, the ground root of the Rubia tinctorium, which contains alizarine, and which up to about 1875 was grown in large quantities for this purpose. The synthesis of alizarine from the hydro-carbon anthracene by Graebe and Liebermann in 1868 laid the foundation for the arti ficial manufacture of this dye-stuff, and also for the great develop ments in anthraquinone chemistry which have followed since. In a few years the natural colouring-matter was entirely replaced by the synthetic, the manufacture of which is effected by oxi dizing anthracene to anthraquinone, converting this into a sul phonic acid and fusing the latter with caustic soda.

The acidic members of the anthraquinone class are represented by alizarine red WS, alizarine acid blues, acid alizarine green, alizarine saphirol, alizarine astrol, alizarine irisol, alizarine cyani nol, alizarine rubinol, alizarine direct blue, alizarine cyanine green, cyananthrols, etc. Many of these dye wool directly from an acid bath without a mordant while others give shades which are faster to washing when a mordant is used (acid-mordant dyes). The vat dye-stuffs of the anthraquinone series are the fastest dye stuffs known. They comprise the indanthrene (duranthrene) series, the caledon series, algol colours, cibanone colours, ponsol colours, etc., the first representative of which, indanthrene blue RS, was discovered in 1901 (vide supra). Many of these dyes have an extremely complex constitution, containing two or more anthraquinone residues united together by other groups or fused in such a way as to produce new ring structures. In these struc tures at least one of the two carbonyl (CO) groups of each anthra quinone residue remains intact, and it is to this group that the property of vat dyeing is to be attributed.

All the anthraquinone dye-stuffs, to whichever dyeing class they belong, exhibit the property of giving upon reduction deeply coloured leuco-compounds which usually reoxidize readily. The colour of these often differs remarkably from that of the original dye-stuff : for example, the leuco-compound of flavanthrene is blue, reoxidizing in air to yellow. The application of stronger reducing agents frequently converts the first leuco-compound into a more stable second leuco-compound from which the dye-stuff is not easily regenerated.

Dye Classes.

In the previous section the synthetic dyes were regarded from the standpoint of their chemical or chromophoric structure. It is now proposed to consider their dyeing properties and the dependence of the latter upon specific constitution or the presence in the molecular structure of particular atomic group ings. In the different categories there will frequently be found representatives of several chromophoric classes (see DYEING).I. Basic Dyes.—The basic dyes are salts. usually hydrochlorides of coloured bases containing amino or substituted amino-groups, such as etc. They dye animal materials —wool, silk, leather, feathers, etc.—directly from a neutral bath, but possess for vegetable fibres, jute excepted, only a small affinity. They are applied to cotton and linen by mordanting these fibres with tannin and a metallic salt, such as a salt of anti mony, which produce insoluble compounds with the dye base. In calico printing, for which dye-stuffs of the basic class find their chief application, a thickened mixture of the dye-stuff with acetic acid and tannin is printed upon the cotton. This is then steamed to drive off acetic acid, leaving the insoluble dye tannate, the fixation of which is completed by passing through a bath of anti mony potassium tartrate. The basic dyes can be applied to jute, hemp and cocoanut fibre without a mordant and are frequently used for dyeing these materials. Some are used for lake pigments for wall-paper printing, while the salts of certain dye bases with the higher fatty acids, oleic, linoleic, stearic or resin acids, are used for colouring oils, varnishes, etc.

The basic dye-stuffs appear to owe their affinity for animal fibres to a chemical combination (salt-formation) occurring be tween the amino or substituted amino-groups of the dye and the carboxylic acid groups of the wool or silk protein. The maximum affinity for these fibres is exerted in a neutral or slightly alkaline bath, and conversely the dye-stuff can be partially re moved from the dyed fibre if the latter is boiled with a dilute acid. Loss of colour on boiling with a 5% solution of acetic acid therefore forms a suitable test for distinguishing dye-stuffs of this class when dyed upon animal fibres. Before testing vegetable fibres (cotton or linen) it is necessary to remove the tannin mor dant by boiling with dilute caustic soda saturated with common salt, which leaves the released dye base on the fibre, from which it can then be removed by dilute acid. The addition of caustic soda to a solution of a basic dye-stuff usually precipitates the dye base, though in a few cases (e.g., safranine) the base remains in solution. The best test for distinguishing basic dye-stuffs from other classes of dyes is the production of an insoluble precipitate on the addition of a solution of tannin and sodium acetate. The most important basic dyes belong to the triphenylmethane and xanthene classes. These are magenta, methyl violet, malachite green, brilliant green, setocyanine, rhodamines, etc. They are remarkable for extreme brilliancy and tinctorial power, but un fortunately their resistance to light leaves much to be desired. Basic members of the azine, oxazine and thiazine classes are safranine, rhoduline reds, spirit-soluble induline, spirit-soluble nigrosine, Meldola's blue, nile blue, capri blue, etc. The azo-class is mainly represented by chrysoidine and Bismarck brown.

II. Acid Dye-stuffs.—These are salts, usually sodium salts, of coloured compounds containing acidic groups, especially the sul phonic group, They dye animal fibres (silk and wool) di rectly from an acidified solution. Certain of them (notably acid violets, wool blues and quinoline yellow) will also dye wool from a neutral bath. For cotton and other vegetable fibres they have little or no affinity, but are used to some extent in the dyeing of jute and book-binding cloths which are not required to be washed. They find their chief application in the dyeing and printing of wool and silk. In the production of lake-pigments many of the acid dye-stuffs are extensively employed (e.g., naphthol yel low, azo scarlets, azo oranges, eosines, etc.), for which purpose they are precipitated as insoluble salts upon a mineral substratum by addition of barium chloride, etc. Certain acid dye-stuffs (lithol reds, lake reds, pigment yellows, monolite reds and yel lows, etc.) are manufactured especially for this purpose.

The acid dyes owe their affinity towards animal fibres to the sulphonic or other acid groups they contain, which doubtless enter into combination (salt-formation) with the amino-groups of the protein molecules. As such combinations have little stability, the dyes of this class are generally deficient in fastness to alkalis and soap, which by neutralizing the dye acid loosen its attachment to the fibre. Loss of colour upon boiling the dyed material with a i % solution of ammonia serves as a convenient test for recognizing this class of dye-stuff. It is to be noted how ever that certain acid dye-stuffs (sulphone cyanines, sulphone azurines, milling reds, etc.) have a higher degree of fastness to alkalis than the normal, which is probably to be referred to the possession by these compounds of a supplementary affinity for the fibre similar to the substantive properties possessed to a greater degree by the direct dyes (see IV. below).

Acid dyes which contain carboxyl groups or hydroxy (OH) groups in suitable positions frequently exhibit an affinity for metallic mordants, by the presence of which their attachment to the fibre can be increased. Such colouring-matters, which oc cupy an intermediate position between acid dyes and mordant fixing dyes proper, are termed acid-mordant or chrome dyes (see III. below). A special class of the latter is supplied to the con sumer in the form of already prepared copper or chromium com pounds, which when dyed from an acid bath give very fast colours (fast acid red RH, fast acid purple, neolans, palatine fast colours, etc.) . Naphthol green B is similarly an acid-dyeing iron com pound of the nitroso-class. Most of the acid dyes are azo-com pounds, e.g., fast yellow, metanil yellow, orange II., acid scarlets, fast reds, carmoisine, lissamine red, naphthalene blacks, etc. The acid dyes of the carbonium class comprise acid magenta, soluble and alkali blues, patent blues, acid violets, acid greens, etc. The eosines, acid rhodamines and fast acid violets belong to the xanthene class, the water soluble nigrosines, water soluble indu lines, wool fast blues, wool fast violets and indocyanines to the azine class. The acid dyes fastest to light are those of the anthra quinone class, namely alizarine saphirol, alizarine irisol, alizarine emeraldol, alizarine cyanine green, alizarine direct blues, etc.

III. Mordant and Chrome Dyes.—These are coloured comIii. Mordant and Chrome Dyes.—These are coloured com- pounds containing particular groups, usually OH or groups, capable of forming stable coloured lakes (co-ordinative com pounds) with metallic hydroxides, particularly with those of chromium, aluminium, iron and copper. The mordant dye-stuffs proper comprise many of the older natural colouring-matters, much as logwood, fustic, cutch, cochineal, Persian berries and brazilwood, but only a few synthetic dyes, which belong chiefly to the anthraquinone class (alizarine, purpurines, alizarine blue, ali zarine cyanines, anthragallol, etc.). Most of the mordant-dyeing colouring-matters of synthetic origin contain acid groups or or both) and may therefore be classified as acid-mordant colours. These are mainly used on a chromium mordant and are theref ore generally termed chrome colours. In wool dyeing the chromium mordant (sodium bichromate, chromium acetate or chromium fluoride) is applied to the wool either before or after dyeing, or even more frequently (metachrome or solochrome colours) both dye stuff and mordant (chromate) are added to gether to the dye-bath. The shades dyed with mordant and acid mordant dye-stuffs are generally much faster to alkalis and there fore to washing and milling than those obtained with ordinary acidic dyes, whilst the resistance to light, more particularly of those belonging to the anthraquinone group, is very good. Mor dant dyes are also employed in calico printing, in which case the solution of the dye-stuff suitably thickened is mixed with chromium acetate and acetic acid, printed upon the cotton cloth and steamed.

Whilst many mordant dye-stuffs are not greatly altered in shade by combination with the mordant, in some cases a com plete change of colour is produced. Thus the yellow alizarine gives a red with aluminium and a purple with an iron mordant; the red chromotropes are changed to dark blue or black by chromium salts or chromic acid; and with the same mordant the red eriochrome azurol becomes blue. A special category of the mordant dye-stuffs are those which also contain basic groups. These may be termed basic-mordant dyes and belong chiefly to the oxazine class (gallocyanines, etc.). They are distinguished from acid-mordant dyes by giving a precipitate with tannin and sodium acetate. The only general method for distinguishing mor dant dye stuffs on the fibre from other alkali-fast dyes, consists in seeking the metallic hydroxide. In the case of chromium this is readily accomplished by burning the dyed fibre and testing the ash. The mordant or chrome dyes of the azo-class comprise the alizarine yellows, milling yellows, palatine chrome red, dia mond blacks, eriochrome blacks, solochrome browns, reds and blacks, and many others. The carbonium class is represented by the eriochrome azurols and eriochrome cyanines ; the xanthene class by gallein, coeruline and ultraviridine ; the thiazine class by the brilliant alizarine blues; and the anthraquinone class by alizarine, purpurine, alizarine cyanines and anthracene blues.

IV. Direct, Substantive or Salt Dyes.—These are colouring matters which dye cotton or other vegetable fibres from a neutral or alkaline solution without the application of a mordant or fix ing agent. They dye animal fibres in a similar manner and also from an acid bath. They are therefore said to have a substantive affinity for these fibres. Like the acid dye-stuffs they are sodium salts of sulphonic acids, but while with the acid dyes it is the free colour acid which is taken up and combined with the fibre, in the case of the direct dyes the compound is absorbed as a whole (hence the term salt dyes). The cause of this direct affinity or substantivity is not precisely known, but it appears to be asso ciated with long-chain structures in the dye-stuff and the presence of hydroxy-groups in the fibre itself. Acetate silk, in which the hydroxy-groups of cellulose are etherified, displays no affinity for these dye-stuffs. The direct dye-stuffs are mainly used in cotton dyeing and printing and in the dyeing of those types of artificial silk which consist of pure cellulose (viscose silk) . For the latter purpose a special class of these dye-stuffs (icyl colours) has been introduced, giving more level shades than the ordinary direct cotton dyes, the affinity of which is frequently too great. Certain direct dyes are also employed in wool dyeing giving faster colours than ordinary acid dye-stuffs (diamine fast red, milling scarlet, etc.) . A few contain mordant-fixing groups and can be dyed upon wool with a chrome mordant or fixed upon cotton by after treatment with a metallic salt (chromium or copper). Certain of these (sirius colours) are supplied as ready prepared copper compounds for dyeing cotton directly in shades fast to light.

The direct dyes are a very numerous group, the principal cate gories of which are the following: (a) Diamine colours, consist ing of azo-compounds derived from diamino-bases, such as ben zidine. These include amongst others Congo red, benzopurpurine, rosophenine, chrysophenine, diamine blues, diamine greens, dia mine blacks and chlorazol colours. (b) J-acid colours, consist ing of dye-stuffs obtained by coupling diazo-compounds with benzoyl or carbonyl derivatives of 2-amino-5-naphthol-7 sulphonic acid. They comprise the benzo fast scarlets, diamine azo scarlets, rosanthrenes and diazo brilliant scarlets. (c) Stilbene dyes, consisting of azo-compounds containing the group : and comprising direct yellow, stilbene yellows and mikado oranges. (d) Thiazole dyes, comprising primuline yellow, Clayton yellow, chlorophenine, erika, diamine pink, gera nine and rosophenine zoB.

V. Developed Colours.—Many of the preceding class of dyes when containing a free amino-group, are capable of being con verted on the fibre into colours of greater fastness or intensity by the process of "development." The dyed material is treated with an acidified solution of sodium nitrite, followed after wash ing by an alkaline bath of 13 -naphthol or other intermediate product. A complex azo-dye is thus built up within the fibre from a simpler one. The process, first applied in 1887 to the dye stuff primuline, which is changed thereby from yellow to red, has since been extended to a variety of "direct-dyeing" azo colouring-matters (diazo blacks, diamine blacks, chlorazol blacks, oxamine blues, diaminogens, diazo scarlets, rosanthrenes, etc.) .

In most cases the shade only becomes deeper or darker and the chief object of the process is to increase the fastness to washing.

Another method of development is termed the "coupling" pro cess, in which the dyed material is passed through a solution con taining a diazo-compound (see Diazo-reactions above), usually diazotized p-nitroaniline. The diazonium salt combines with the dye on the fibre, to yield a more complex compound, having a deeper shade and increased fastness to washing. This process is applicable to the benzonitrol browns, toluylene browns and diamine nitrazol colours.

VI. Sulphide Dyes.—These colouring-matters, belonging to various chromophoric classes, possess in common the property of dyeing cotton from a bath of sodium sulphide. They are pro duced by heating various intermediate compounds, mostly of the aminophenol class, with sodium polysulphides. The dye-stuffs themselves are insoluble in water but dissolve, probably as leuco compounds, in an aqueous solution of sodium sulphide, from which solution vegetable fibres are dyed in shades of remarkable fastness to washing. Although their structure is not as yet fully ascertained, it seems certain that they owe their dyeing properties, which are akin to that of the "vat" dyes, to the presence in the molecule of a chain of sulphur atoms, –S–S– or –S–S–S–S, which upon reduction in an alkaline medium yields a soluble sulphydrate –SNa or –S–SNa. This is taken up by the fibre and by aerial oxidation regenerates the insoluble dye.

The sulphide dyes belong to several chemical classes : the blue and black members contain the thiazine grouping; the pur ple and maroon members the azine grouping ; the yellow, orange and brown members, the thiazole grouping. The most important are the sulphide or sulphur blacks, which are very largely used and compete with aniline black in cotton dyeing. The blue members (thianol blues, immedial blues, pyrogene blues, etc.) are used as substitutes for indigo, while the yellows and browns (thianol yellows and browns, etc.) are employed for dyeing khaki and cutch shades. The chain of sulphur atoms to which the sulphide dyes owe their dyeing properties is somewhat unstable, and under the influence of acid reducing agents, such as stannous chloride and hydrochloric acid, a part of the sulphur is split off as hydro gen sulphide, readily detectable by lead acetate paper thus giving a convenient test for dyes of this class. Though tolerably fast to light, the sulphide dyes are readily attacked by hypochlorites (used in bleaching) even in weak solution.

VII. Vat Dyes.—This term is applied to dye-stuffs which, Vii. Vat Dyes.—This term is applied to dye-stuffs which, being insoluble in water, are applied to the fibre in the form of their alkali-soluble leuco-compounds, followed by reoxidation by air. Indigo is the typical representative and was formerly the only example of this class. During the present century, however, many new dye-stuffs have been discovered having similar dyeing properties and exhibiting a great variety of shades. These colours meet modern demands for a high degree of fastness, not only to wards alkalis and washing but also for the most part to light, bleaching and other agencies. Owing to the insolubility in water of the dye-stuffs themselves, these products are usually sold in the form of pastes generally containing 2o% of dry dye-stuff.

The property of dyeing "in the vat," i.e., in a similar mannef to indigo, may be referred to the capacity of forming leuco compounds of weakly acid properties which possess an attraction for the fibre and are readily reoxidized by air. In the case of the vat dyes of the indigoid and anthraquinone classes this property is attributable to the presence in the molecule of > C:O groups, which by alkaline reducing agents are converted into /CC OH groups and their soluble alkali salts. In the sulphide-vat colours it is doubtless due to chains of sulphur atoms, similar to those present in ordinary sulphide dyes but not so easily reducible. Attempts have recently been made to simplify the dyeing opera tions for vat colours by preparing soluble stable derivatives of their leuco-compounds containing "labile-acidic" groups, which derivatives can be applied to the fibre and afterwards treated with an oxidizing agent such as ferric chloride or nitrous acid, when the labile-acidic group is eliminated and the insoluble dye becomes fixed on the fibre (indigosols and solindone colours).

The vat dye-stuffs may be subdivided into the following cate gories: (a) Indigoid vat colours, comprising indigo and thio indigos, ciba colours, durindones, helindone colours, etc. They are applicable to both animal and vegetable fibres. Reduction is usually effected by means of sodium hydrosulphite, though in the case of indigo itself, other reducing agents are sometimes used (fermentation vat, etc.). (b) Anthraquinone vat colours, com prizing the indanthrenes, duranthrenes, algol, cibanone, ponsol, carbanthrene and caledon series. They are employed in dyeing and printing cotton and linen, upon which materials they produce the fastest colours known. They have not yet found general appli cation in wool and silk dyeing owing to the fact that the reduc tion by sodium hydrosulphite requires the presence of strong alkalis. (c) Benzoquinone and naphthoquinone vat dyes are at present only a small class comprizing certain vat browns and yellows employed in wool dyeing (helindone series). (d) Sulphide vat colours, mainly represented by the hydrone blues, derived from carbazole, probably contain the thiazine chromophor. They are closely related to the ordinary sulphide dyes, from which they only differ in their method of dyeing and greater fastness. They are employed for vegetable fibres only, upon which they are applied from an alkaline bath of sodium hydrosulphite. The hydrone blues dye cotton in indigo blue shades of great fast ness, superior in some respects to indigo. They give upon reduc tion nearly colourless leuco-compounds, which readily reoxidize upon exposure to air. They are not sublimable upon heating and cannot be extracted from the fibre by pyridine (distinction from indigo) .

VIII. Pigment Colours.—Under this heading may be classed Viii. Pigment Colours.—Under this heading may be classed synthetic colouring-matters which are insoluble in water and are not applicable for textile dyeing in the usual way. Certain azo dyes when generated upon or within the fibre produce very fast shades (such as Para red, dianisidine blue and the azoic colours). Prepared in substance certain of them are used for colouring oils, waxes, varnishes, etc. (sudans and oil colours) ; while other mem bers of the class which are insoluble in oils are used for oil-colour and lithographic printing (hansa yellows, pigment red, monolite fast scarlet, typophor colours, etc.) . Insoluble dye-stuffs of the indigoid and anthraquinone classes, especially prepared in a finely divided condition, may also be similarly employed.

The insolubility in water of these pigment dyes is due to the absence of strong salt-forming groups, either acid or basic. Cer tain soluble dye-stuffs can also be converted into insoluble com pounds by precipitation as barium or aluminium salts (presence of or OH groups), or as tannates, phosphates, sili cates, phosphomolybdates (presence of or other basic groups) . The insoluble compounds thus formed are termed lakes or lake pigments, and are also largely used in the paint, wall paper and printing-ink industries, the dye-stuffs particularly suited for these uses being the lithol yellows and reds, monolite yellows and reds, lake scarlets and many of the ordinary acid and basic colouring-matters.

IX. Acetate Silk Dyes.—The particular kind of artificial silk which consists of acetylcellulose and is known as "Celanese," is only dyed by a few acidic dye-stuffs and by some of the basic dyes. For the majority of the acidic dyes and for the entire class of the direct dyes this fibre exerts no affinity whatever. To over come the difficulties encountered in dyeing this material, special colouring-matters have been introduced. The first of these new classes were the ionamines, in which insoluble compounds of azo or anthraquinone series are converted into temporarily soluble derivatives by the introduction of methyl— w —sulphonic groups, These groups are split off during dyeing and the in soluble dye-stuff formed is absorbed by the fibre. Another class, the S.R.A. colours, consists of insoluble azo-dyes maintained in colloidal suspension by means of sulphonated castor oil; while in the duranol series the same principle is applied to insoluble dyes of the anthraquinone class. In addition to dyeing fast shades upon acetate silk, all these dyes have the further advantage, that they exert no affinity for cotton, linen or viscose silk, and can there fore be employed together with direct dyes for producing two colour effects upon fabrics woven from these fibres together with acetate silk.

X. Food Dyes—This class of dye application has been de veloped particularly in the United States where the Government officially "certifies" as to purity of even individual factory lots of a dozen selected dyes, in which case the lots in question can be sold as certified dyes. The selected dyes are mainly naphthol yellow S, yellow OB, poncean 3R, orange I, amaranth, tartrazine, guinea green B, erythrosine and indigo disulphonic acid. They are chosen for their harmlessness when properly made, and for their food (candy, iced drinks, confectionery) colouring ability. The amount sold in the United States in 1926 was 141 tons valued at $I,I15,000 4228,000).

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-G.

von Georgievics and E. Grandmougin, Text Bibliography.-G. von Georgievics and E. Grandmougin, Text Book on Dye Chemistry; F. M. Rowe, The Colour Index (1924) ; J. C. Cain, The Manufacture of Intermediate Products for Dyes (1919), and The Manufacture of Dyes (1919) ; H. E. Fierz-David, The Funda mental Processes of Dye Chemistry, trans. from the German by F. A. Mason (1921) and Kunstlicher Organische Farbstoffe (1926) ; A. G. Green, The Analysis of Dyestuffs (1916) ; A. Wahl and F. W. Atack, Organic Dyestuffs (1914) ; S. C. Bate, Synthesis of Benzene Derivatives (1926) ; A. Davidson, Intermediates for Dyestuffs (1926) ; E. de B. Barnett, Anthracene and Anthraquinone; H. M. Bunbury, Coal-tar Products (1926) ; Allens' Commercial Organic Analysis (1928) ; W. B. O'Brien, Factory Practice in Manufacture of Azo Dyes (1924) ; A. E. Everest, The Higher Coal-tar Hydrocarbons (1927) ; Census of Dyes and Organic Chemicals (1924 et seq., U.S. Tariff Commission, Washing ton) ; R. N. Shreve, Dyes Classified by Intermediates (1922) ; H. Bucherer, Lehrbuch der Farbenchemie (1914) ; R. Staeble, Die neueren Farbstoffe der Pigmentfarben-Industrie (191o) ; O. Lange, Die Schwefel-Farbstoffe (1925) ; J. Formanek, Spektralanalytische Nach weis kiinstlicher organischer Farbstoffe (190o) ; P. Friedlaender and H. E. Fierz-David, Fortschritte der Theerfarbenfabrikation (1877 to 1925) . (A. G. G.) The genesis of the synthetic dyestuff industry is found in the discovery of aniline purple, or mauve, in 1856 by W. H. Perkin, in the course of an attempt to prepare quinine from aniline. Manu facture was commenced in the following year by Perkin and Sons, at Greenford Green, near Harrow, England, and in Dec. 1857 this colour was in commercial use for the dyeing of silk. Two years later Verguin in France, also experimenting with aniline, obtained Magenta, which was followed by Violet Imperial and Bleu de Lyon (Girard and de Laire), and in 1862 by Nicholson's Blue, the first soluble acid dye for wool, whilst in 1863 aniline yellow, the first representative of the vast group of azo colours, was introduced by Messrs. Simpson, Maule and Nicholson. At this period the manu facture of dyestuffs was mainly confined to England and France.The possibilities of the new industry, however, were attracting attention in other countries, and it was in Germany that the most fertile soil for its development was found. In 1868 Graebe and Liebermann made the important discovery that Alizarine (mad der) could be prepared from anthracene, a constituent of coal tar, and the synthesis of the first natural colouring matter was effected. Manufacturing processes were patented simultaneously by Perkin in England, and in Germany by Caro, Graebe and Liebermann, and in 1869 production commenced. The rapidity with which the natural product was driven from the market is shown by the de cline of the British imports of madder from 15,300 tons, value 1690,000, in 1868, to 1,650 tons in 1878, the total value of the world's madder trade in the former year being £2,000,000. Perkin and Sons produced 4o tons of Alizarine in 1870, and 435 tons in 1873. The Badische Aniline Company in Germany commenced production in 1871 with 150 tons, which during 1873 had risen to 1,000 tons.

Large profits were now being made both in Great Britain and elsewhere, and in 1874 Perkin retired from the business, which was taken over by Messrs. Brooke, Simpson and Spiller. Further im portant discoveries were announced from Germany with, in 1874, the Eosines, in 1876 Methylene Blue, the first basic blue soluble in water, and in 1877 Malachite Green, the first green of real dye ing value; and the supremacy of the German manufacturers was by now definitely established. The value of the production of dye stuffs in 1878 is given at 13,150.00o, participated in as follows:— Germany . . . 2,000,000 France . . . . 350,000 Great Britain . . 450,000 Switzerland . . . 350,000 Later landmarks in the development of the industry were the introduction (188o) by Read Holliday and Company of Para Red, the first dyestuff to be produced on the fibre, and the discovery in Germany in 1884 of Tartrazine as well as of Congo Red, the first colour having direct affinity for cotton. In 1885 only 20% of the synthetic dyestuffs consumed in Great Britain were of home manufacture.

In 1880 Von Bayer succeeded in preparing indigo by synthetic means. In 1897 after an expenditure of £900,000 had been in curred by the development work, synthetic indigo was marketed. At this time the annual value of the world's growth of indigo was about 14,000,00o; in India alone 1,400,000 acres of land were de voted to this crop, but a continuous decline set in and by 1912 the Indian area had fallen to 214,00o acres. The German production of the synthetic product, which in 'goo was about 2,500 tons, had increased to 39,00o tons in 1913. Cultivated indigo thus met the fate which 40 years earlier had befallen the madder root.

The Pre-War Output.

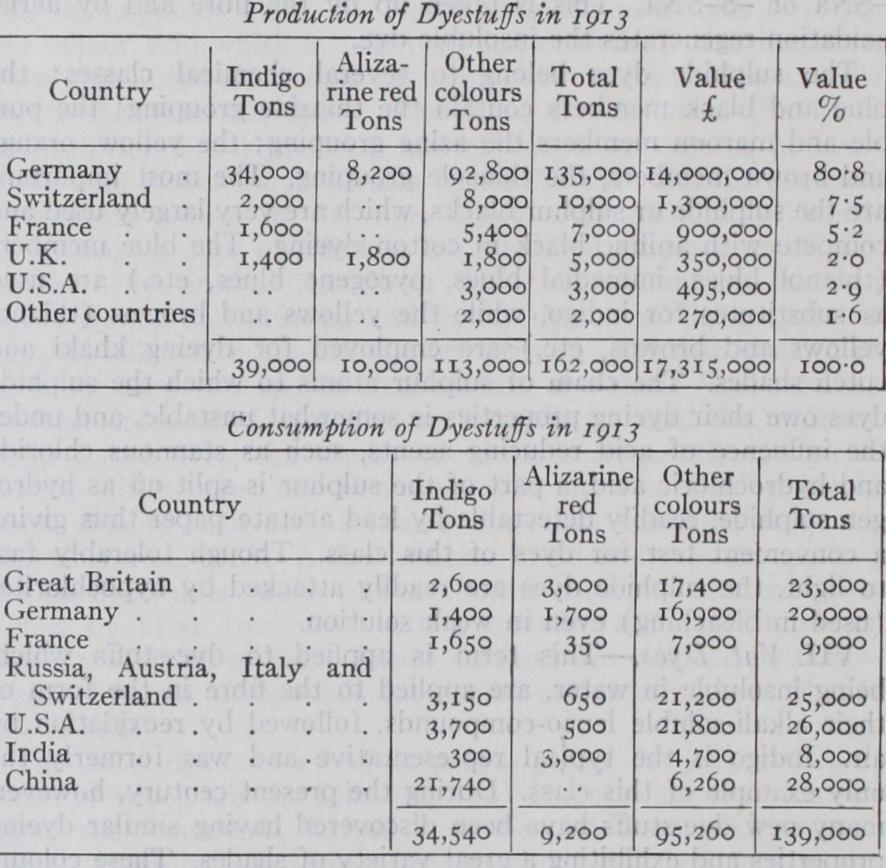

The position of the dyestuff industry in 1913 is shown by the following statistics of production and consumption :— The predominance of Germany at this time was even more pronounced than the above figures indicate, since a considerable proportion of the output shown for Switzerland, Great Britain and other countries was manufactured from "intermediates" which were of German origin. In Germany the organic chemical indus try, of which dyestuffs manufacture was the mainstay, was developed on the broadest lines, supported by the banks, and directed by University trained scientists. By 188o two German works were employing sixty scientific chemists. In 1900 six firms employed 500 chemists, 35o engineers and technologists and 18,00o workpeople. In Great Britain at the latter date the cor responding figures were 3o to 4o chemists and 1,000 workpeople. Whereas between 1886 and 1900 German firms obtained 948 patents for the manufacture of dyes, British firms took out only 86, the ratio of the number of patents closely corresponding to that of the number of chemists employed.

Modern Developments.—Such was the position in 1914 at the outbreak of War. Britain was then importing annually, at a cost of 12,000,000, dyes essential to industries producing goods valued at upon which 1,500,00o workers were de pendent. The United States consumed annually 26,000 tons of dyes of which 3,00o tons only were home manufacture, the total consumption being valued at 14,000,000. In all countries from which supplies of German dyes and drugs were cut off a serious shortage rapidly supervened. Industrialists realized that although dyes were in respect of cost a minor item amongst their raw materials, they were an essential commodity to make the products saleable.

In Great Britain and the United States steps were quickly taken to stimulate production, and Government assistance was invoked. In the former country enemy patents were revoked, and the chief existing producers, Messrs. Levinstein Ltd. and Read Holliday and Co., rapidly expanded their output. The latter firm was bought out in 1915 by British Dyes Ltd., a company promoted with financial assistance by the Government and largely subscribed to by the dyestuff consumers. Processes required to be worked out, buildings and plants constructed, chemists trained. Government requirements for the war were paramount, these consisting not only of khaki and blue dyes for the army and navy, but of explo sives. By 1917 the essential requirements of the country were being fully met. Alizarin had been produced in quantity for many years by the British Alizarine Co., a company formed by the Turkey Red Dyers Association in response to a German threat to increase largely the price. The British production of dyes in 1918 amounted to 13,600 tons. In 1918 an amalgamation of British Dyes Ltd. and Levinstein Ltd. was effected under the style of British Dyestuffs Corporation, Ltd. A new company, Scottish Dyes Ltd., concentrated on the production of the important fast to light vat dyes produced from anthracene. France, Japan and Italy, each formerly dependent upon German and Swiss supplies, similarly developed the industry, and by 1919 all the above countries were capable of supplying, in bulk, 8o% to over 9o% of their home requirements, as well as of exporting considerable quantities to the Chinese and Indian markets.

The world's annual capacity to produce dyestuffs was now at 300,00o tons, almost twice the capacity in 1914. Over production and severe competition were everywhere experienced with the return of the German colours to the market, and each of the pro ducing countries adopted measures for protecting their home trade. The United States, Italy and France, created high import duties. Japan subsidized the industry and instituted a licence system of import control. Great Britain by a Proclamation in 1919 pro hibited imports except under licence from the Board of Trade. A test case, however, resulted in a judgment that this procedure was illegal, and throughout 1920 there was no restriction, dyes to the value of £7,500,000 being imported. This severe blow dealt to the British industry was followed shortly by a world-wide slump in trade. The Dyestuff (Import Regulations) Act was passed, be coming operative in Jan. 1921, whereby for a period of ten years importation of dyestuffs and intermediates was only permitted under licence. Licences are granted if the corresponding product is not offered by the home producer, and also on price grounds. Initially the British manufacturer was required to supply at a price not exceeding three and a half times the established pre-war price, this factor having been since successively reduced to 3 times, 21 times and in 1927 to twice the pre-war figure.

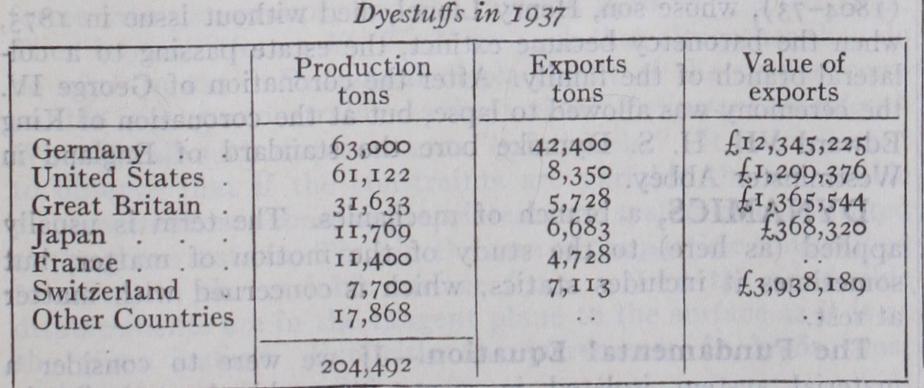

In 1923 the French occupation of the Ruhr, which resulted in the shutting down of the principal German factories and the seizure and export of large stocks of dyes, was a disturbing factor in the international dyestuff situation, and the first normal years subsequent to the war were those of 1924 and 1925. The statistics for the year 1937 are given below; these represent the latest available figures of international dyestuff production.

The total production in bulk is 26% higher than 1913, the Ger man production having fallen from 83% to 31%. While Germany still holds first place as an exporting country, however, dye stuff production in Great Britain and the United States increased tremendously and the range of dyes manufactured is sufficiently diversified to make these countries independent of outside sources of supply. Italy also made considerable progress in the dyestuff field producing 13,800 tons in 1937. The high value of the German exports in comparison with those of other countries excepting Switzerland is due to concentrations on the more ex pensive types of dye, in particular, of the vat colours, in the manufacture of which the newer producing countries were then less able to compete. (M. BA.; X.) In the United States prior to 1914 about 104 dyes were manu factured almost wholly from imported intermediates, and depend ence was largely upon Germany. The famine of coal-tar products which followed the outbreak of the war led to the establishment of the manufacture of intermediates and dyes on a large scale, so that by 1919, 25o and by 35o types of synthetic dyes were being manufactured. The indanthrene or vat dyes were the last to be offered by American manufacturers, the output in 1924 of such vat dyes other than indigo being 1,821,319 pounds. This increased by 43% to 2,608,361 lb. in 1925. In 1923 production had reached so satisfactory a state that 96% of domestic con sumption was met in the country and there was in addition an ex portable surplus of 18,000,00o lb. of dyestuffs. Since 1917, the annual progress of this branch of the chemical industry has been published in detail in the annual census issued by the United States Tariff Commission. In 1937, 43 firms were engaged in the manufacture of dyestuffs, producing more than 1,000 distinct types having a sales value of $64,613,000. Of this total vat dyes other than indigo accounted for $13,110,000 or about 20 per cent.

Early in the war it became evident that many enemy-owned American patents were being used to interfere with production in cident to the successful prosecution of the war. These patents, some 4,000 in number, were taken by the alien property custodian and later sold to the Chemical Foundation, Inc., formed for the purpose of administering these patents for the public good. Any profits above 6% earned on a comparatively small capital stock are devoted to scientific research and educational activities. The Chemical Foundation, Inc., was later sued by the Government for the return of these patents, the case going to the Supreme Court, and the Chemical Foundation being sustained in the district, the appellate, and the supreme courts.

While the sales value of dyestuffs is not large when compared with many other American industries, its importance lies in the fact that others having great values are dependent upon it. It is for this reason a key industry. Textiles and textile products, paper and allied products, leather, ink, and carbon paper are among the industries dependent upon an unfailing source of dye stuff supply, for their practical existence and their products are valued at several billions of dollars annually. Furthermore, the dyestuffs group is the foundation of the entire organic chemical industry. From it has grown a large business in such products as medicinals, flavours, and perfume materials, rubber chemicals, resins, and miscellaneous coal-tar chemicals amounting in 1937 to an additional $64,123,000. The manufacture and sale of synthetic organic chemicals not of coal-tar origin in 1937 produced items to the value of $119,420,000.

At an early date the manufacturers of dyestuffs placed depend ence upon scientific research, established extensive laboratories for the purpose, and encouraged the training of suitable personnel through the establishment of numerous fellowships in educational institutions. In 1934, 129 separately organized research labora tories were in operation, employing about 1,350 technically trained persons. Net cost of research for that year was about $8,000, 000 or 4% of the sales value of all synthetic organic chemicals.