The Requirements of a Drawing

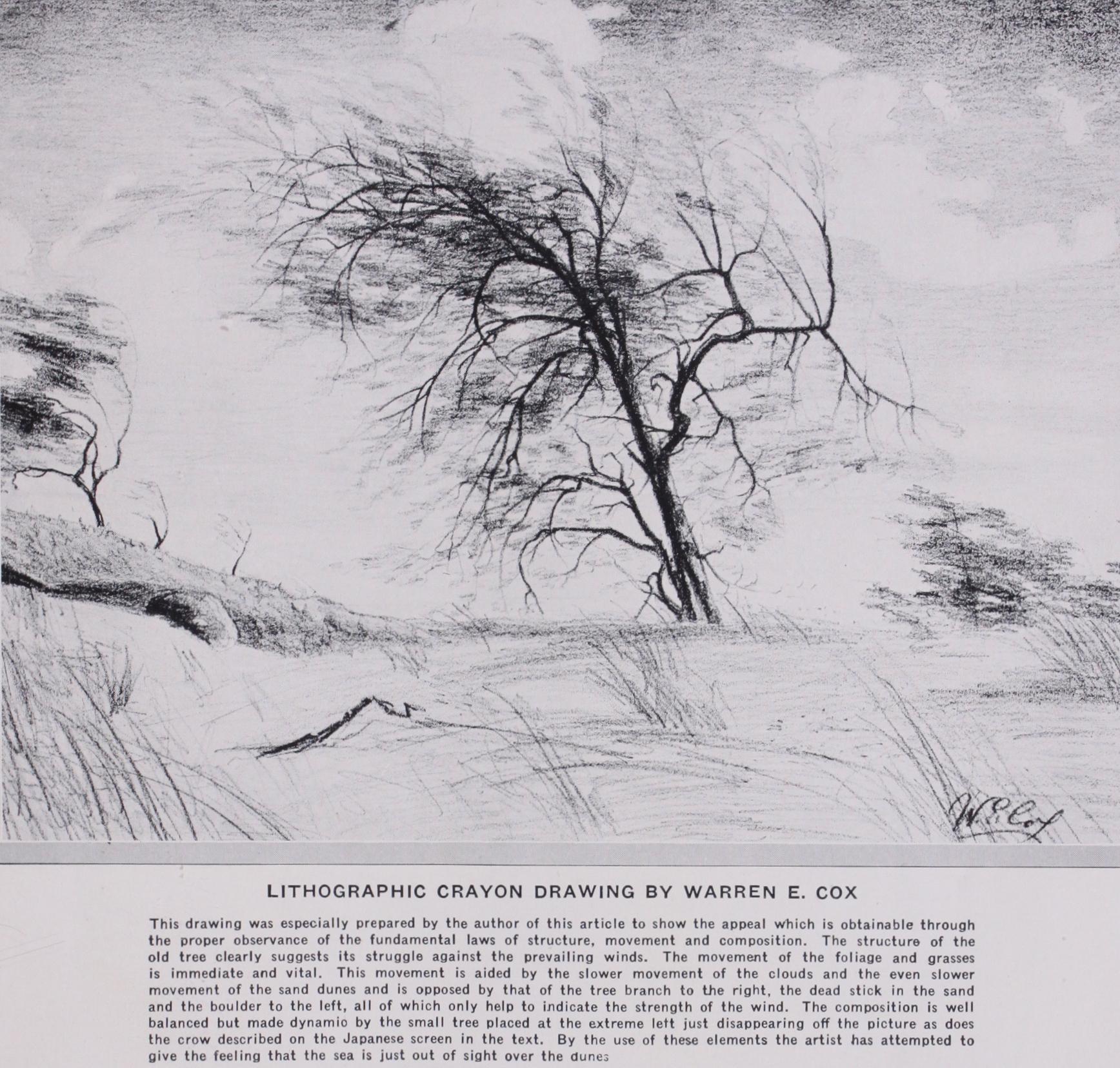

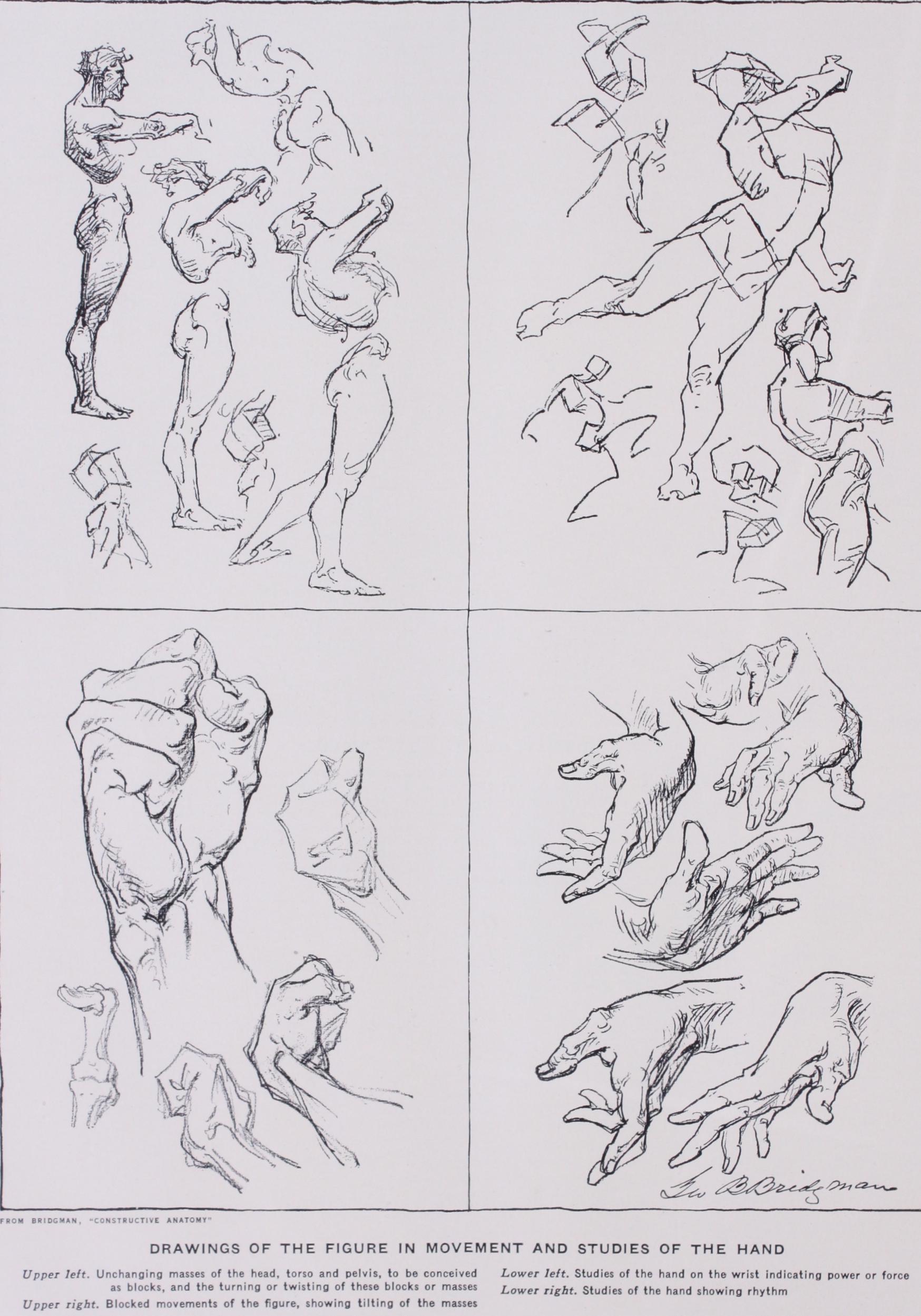

THE REQUIREMENTS OF A DRAWING Even more practice and observation are necessary to catch the movement which is also one of the fundamental appeals of good draughtsmanship. First it must be understood that there is movement in everything. Trees, when well drawn, seem to show how through years they have twisted and grown up out of the ground. Rocks show the bending of their hot masses by volcanic eruptions and the splitting and eroding of their surfaces. Just as each thing has characteristic structure and outline so too has it characteristic movement, and this movement must be caught in the drawing and should be emulated to a degree in the very movement of the lines. One does not draw the placid sea of a summer night with the same quality of line and movement as one would use to portray its raging strength in a storm. With out typical movement a drawing lacks life and therefore interest. The savage all over the world typifies a snake by a simple wavy line showing its motion, and he feels that an animal is "not him self" in a drawing, if not shown in typical movement.

Composition.—Closely related to these three fundamental requirements in good drawing is a fourth which came into the con sciousness of man undoubtedly at a later date, but thousands of years ago, that is, composition. No doubt the first artists drew without any consideration of a boundary or limitation to their work, but at some time in the dim past, in the decoration of a clay vase or some other object, a discovery was made that the design was related to the space in which it was executed. Slowly through thousands of years drawings were developed which seemed to be a part of the structure of the limitations or borders themselves ; outlines were so related that the eye of the observer was held within the limited area and led from one im portant detail to another, and it was found that movement was somewhat assisted by the proper placing of figures in the surround ing border.

Much has been written about composition. The Far Eastern artist is perhaps its greatest master. After observing carefully the object to be drawn, he sits and looks at the piece of silk or paper upon which he is to work and plans where he is to place the main features. He does not start at once to sketch as do many of our western artists, for he has found that once the pencil or brush is touched to paper one's ideas crystallize and it is difficult to get away from the slightest commitment. It is, therefore, much better to keep the mind at first in a fluid state so that the final arrangement can be unhampered and things can take their proper relationship.

Simple proportions in composition are easy to grasp and have more meaning than have those proportions which the eye does not understand. Rhythmical or parallel movements are interesting methods of accenting what seem to be the most typical lines and are often used. Perfect symmetry is tiring. It is as though one were to sit upright in a chair for a long time. The balance should then be thrown to a greater or lesser degree away from the centre to indicate the movement of the picture and give it ease. The story is told of a famous artist in Japan who was asked to paint a screen for the emperor, showing crows in flight. He at length painted one crow just disappearing off of the fourth panel, leaving the other three untouched. Thus composi tion helped the movement of the drawing, and the finished work is famous.

If these four simple laws of drawing are observed, it is possible that the finished work will be excellent, but, if any one be omitted, this is impossible. Man has for so long learned to observe struc ture, outline, movement and composition that the most casual observer feels a lack, if the work does not show them all. Good modelling, perspective and all other considerations can be neg lected, and yet a drawing may be a masterpiece aesthetically, though there is no doubt that these do add to its appeal. But these four elements do not in themselves make a great work of art but rather their proper balancing and expression, which may be called taste.

Good Taste.—In considering taste it is first necessary to understand what enters into a good drawing, or any outstanding work of art. The personality of the artist or his style is a great part of it and this may be dashing and strong or delicate and sensitive; it may be keen and light, or ponderous and powerful. There are as many styles as there are artists and much of the love that people have for some works of famous artists is due to the fact that these works give some idea of the man himself. There is also the medium used, be it drypoint, graphite, etch ing, lithographic crayon or brush, and each medium has ad vantages and disadvantages. The drypoint line is strong and delicate without much flexibility but with a burr which is dis tinctive. The etched line has a sure clean-cut quality, but neither admit the soft shading possible with the pencil and the crayon or the flexibility of the brush. The appropriateness of the medium and its adaptation to the subject expressed are considerations often neglected, for artists sometimes become used to one medium alone and never find out the possibilities of the others. Finally there are the mood and character of the subject to be expressed. The woodlands which Corot chose to paint seemed to be a part of an enchanted world. The jagged rocks crashing into heaven which Li Lung Mien so deftly rendered with his brush are like flames crackling against the sky. These artists added much of their own imagination to what already existed ; but it is never theless necessary to have something to start with, and without having seen the elms of France Corot would have found it difficult to paint, as would Li Lung Mien without the rough mountains of China.

Good taste is the perfect fusion of the personality of the artist through long years of practice into a skilful wielding of the tool, which in turn expresses the vital and inner meaning of the object portrayed with all due attention to its structure, its typical sil houette and motion, with appropriate and reasonable composition. When a thing is drawn in good taste one can see what the artist felt while drawing and what his reactions were to the subject shown. Each mark on the paper not only tells how he felt and what his mood was, but what he saw in the mood of the subject. If his subject be a gladiator he may have felt the glory of battle, the vigorous strength, the cruel beauty of the contest ; or on the other hand he may have felt the pity and pathos of the inevitable destruction of so beautiful a body. In the one case his strokes would be sharp and vigorous ; in the other heavy and dull. More over the composition, structure and movement would also re flect both the artist's feelings and those of the subject ; both the artist's soul and that of the subject for it is only in this dual expression finely balanced that we ever find the really great works of art.

Some artists fail in good taste because they are so self-centred that they portray everything with too much of themselves and too little of the subject in the work. Others fail because they are so weak that they attempt a totally different treatment for each subject and have nothing to say about any. A drawing may also be in good taste in its expression of line, in its balance of the subjective and objective, but fail because the composition has not been studied to express this condition and is therefore not appropriate. Drawing is like music : it has tempo, key, pitch and many other elements, all of which, when perfectly handled by a master, make for beauty ; but which, in the hands of one untrained or unfeeling, may prove terrible pitfalls.

Three Dimensions.

In this discussion nothing has been said of the attempt to portray three dimensions on a two dimensional surface (see PERSPECTIVE). It is the consensus of opinion that a work of fine drawing can be just as great in two as in three dimensions. Nay, it has often been pointed out that drawing is fundamentally two dimensional art and that the introduction of the third dimension savours of trickeries, and either builds lumps on the two dimensional surface or pushes holes into it. However, since the discovery of perspective, such superb trickery is it that a great vogue for its use has sprung up, and in the development of realistic painting which found its apex in the early i9th century much was done to make man expect the third dimension in drawing. Others, led perhaps by Cezanne, have attempted to give an even greater feeling of solidity to objects by the use of exaggeration and distortion. This is all interesting and may, in thousands of years to come, grow so into the con sciousness of man that children drawing in the sand with a stick will spontaneously depict the third dimension, but at present it is a comparatively new development and has not yet penetrated deeply enough to make it one of the fundamental renuisites. A work of art can be a masterpiece if drawn in only two dimensions and does not gain an appreciable aesthetic advantage, if drawn in three.

The Teaching of Drawing.

Owing to a faulty understand ing of terms and a general misunderstanding of the underlying principles of art there has been a great effort in the last generation to teach "originality" and individual expression in all the arts. One might as well try to teach character or soul. These are things which grow through the years and which cannot be taught. The result is a chaotic condition hampered by the belief that artists are born, and that they express their "gift" suddenly and without the work which a careful study of the lives of all great masters proves to be necessary. Some schools do not feel it is necessary to teach the pupils the fundamentals of art, so cautious are they in the foolish effort to protect their pupils' freedom. Therefore it seems necessary to consider the sane and proper method which should be followed in the instruction of others or of self.First of all, become friendly with a ruler. A large part of the artist's work consists in measuring with the eye, and it is impera tive that the eye be trained to accuracy. Only by judging dis tances and proportions and then checking one's judgment by measurement can this accuracy be obtained. A good plan for the beginner is to purchase a drawing board, T square, triangles, compasses and pair of medium size calipers. With these instru ments an attempt should be made to draw vases of simple form so that the eye may be trained to see curves and proportions. For example (see fig. 5) after the piece of paper is fixed to the board with thumb-tacks (drawing pins) so that its lower edge is in line with the T square when pressed in place at the left side of the board, a line is drawn near the bottom to act as base line and upon this line a portion is measured off with a ruler, equal to the diameter of the base. This line is then divided in half and a perpendicular is erected at its centre, upon which the height of the vase is laid off ; at this point another horizontal line is drawn, upon which is laid off the diameter of the lip centred immediately above the base. The ruler is then stood perpendicular to the table upon which the vase stands and moved until it touches the side of the vase at a point where it is widest, and another horizontal line is drawn with the T square, the same dis tance from the base line as this point is from the table. With the calipers this widest diameter is found and it is laid off on this line. Similar measurements are taken of the narrowest diameters and of their height from the table, and finally the curves are drawn in, touching those points which have been established.

It will be surprising to the be ginner to find how accurate his first drawing is, if done in this manner. It will also be surprising to find how quickly he can grasp the amount of concavity or convexity of a curve no matter in what position it may occur ; and to grasp its changes into an other curve after he has drawn a number of vases. He will begin to see where one curve becomes more abrupt and another more gentle in its course. Looking back upon his first drawing, he will see all the slight delicacies of line which he missed, and will begin to appreciate the fine innuendoes the potter had put into the vase, which had at first completely escaped his eye.

The modernist may criticize this method and say that it will make the student a slave to the ruler. This is not true, for as time goes on the student needs fewer and fewer actual measure ments, until at length he can draw a vase on any scale accurately. It is then time to attempt more complicated forms and these too should be measured at first. The greatest sculptors do not entirely trust their eyes for this work, and it is only by long training and much hard though interesting work that real efficiency can be accomplished, but new beauties will reward the student at every turn as he begins to train his eye to see. There is time enough later to try certain distortions or caricatures of the ob jects, to gain points which it is wished to stress. These distor tions must be based upon correct drawing, or they will not be convincing. During this training the student should constantly observe masterpieces of various kinds, and remember that master pieces are not only paintings which hang in museums but vases, sculpture, furniture and all of the thousand and one other things which show the touch of real art. The East should be studied as well as the West and every thing which especially appeals should be copied; for it will be found that one sees into a thing much more, if it is actually copied, than one can by any amount of mere looking at it. Through all of this study, the principles which were first pointed out should be kept in mind and an attempt should be made at all times to incorporate them in the actual work as it goes along. (W. E. Cx.)