Elbe

ELBE. The Elbe (Albis of the Romans, Labe of the Czechs), is a river of Central Europe, rising in Bohemia on the southern side of the Riesengebirge at an altitude of about 4,600 ft. The Elbseifen, after plunging down the 140 ft. of the Elbefall unites with the steep torrential Weisswasser at Madelstegbaude. There after the united stream of the Elbe pursues a southerly course, turning sharply to the west at Pardubitz and at Kolin bends gradually towards the north west. A little above Brandeis it picks up the Iser and at Melnik the volume of the stream is more than doubled by the Vltava (Moldau) which runs northwards through the heart of Bohemia; at Leitmeritz the Elbe receives the Eger. Thus augmented the Elbe carves a path through the basaltic mass of the Mittelgebirge through a deep narrow rocky gorge, then the river winds through the fantastically sculptured mountains of "Saxon Switzerland" (Bastei).

Shortly after crossing the Czechoslovakian frontier the stream assumes a north westerly direction, which it preserves on the whole all the way to the North Sea. After leaving Saxon Switzer land at Pirna, the Elbe rolls through Dresden, afterwards entering on its long journey across the north German plain, touching amongst other places, Wittenberg, Magdeburg and Hamburg, and gathering the waters of Mulde and Saale from the left and those of Schwarze Elster, Havel and Elde from the right. Above Ham burg the stream divides into Norder and Slider Elbe, linked to gether by several cross channels. At Blankenese, seven miles below Hamburg, all these branches have been re-united. and the Elbe, with a width of miles between bank and bank, travels on between the green marshes of Holstein and Hanover until it be comes merged in the North Sea off Cuxhaven. The width is about ft. at Kolin, 30o ft. at the mouth of the Vltava, 96o ft. at Dresden and over i,000 ft. at Magdeburg. From Dresden to the sea the river has a total fall of only 28o ft. over a distance of about miles. The tide advances as far as Geesthacht ( too miles from the sea) . The river is navigable as far as Melnik (525 miles, of which 67 in Czechoslovakia) . Its total length is 725 miles (190 in Czechoslovakia) . The area of the drainage basin is esti mated at 56,000 square miles.

Navigability.

Since 1842, but more especially since 1871, the riparian states have carried out works to increase the naviga bility of the Elbe. From the point of view of navigation on the Elbe-Vltava system, three different sections are to be distin guished. (I) The canalised section, (2) the regulated section and (3) the maritime section. The canalised section includes the Vltava from Prague to Melnik and the Elbe from Melnik to Lovosice. Shortly the canalisation will go as far as Usti, after finishing the Strekov dam. In this section, 115 km. long, the navigable channel has a minimum depth of 2M10. The normal largest type of barge now in use has a carrying capacity of 900 tons. The draft at full load does not exceed im80. This section of the river therefore meets all traffic requirements. The canali sation is effected by locks and movable dams, the latter so de signed that in times of flood or frost they can be dropped flat on the bottom of the river. The regulated section between Usti and Hamburg, 649 km. long, has been regulated at middle water. The depth of the navigable channel varies according to the water level, which is dependent on general hydraulic conditions. The loading capacity of 90o ton barges can be fully utilized during about 220 days and for 4 during about 8o days. (In 1925, owing to shortage of water, this period was considerably less.) The German programme for improvement works establishes a depth of 1m.2 5 below and im. t o above the Saale mouth at the lowest water level. Czechoslovakia also contemplates the improvement of its section below Usti. The maritime section between Hamburg, Harburg and the sea, long about 15o km., has an average depth of 9m.5o. (Near Oste-bank 8 m. below average low water level.) Unremitting efforts are being made to meet the constantly increas ing draught of vessels. All vessels can go up to Hamburg at high water.

Canals of the Elbe River System.

During the last quarter of the 19th century some too miles of canal were dug for the purpose of connecting the Elbe through the Havel and the Spree with the Oder system ; the Spree has also been canalized for 28 miles. Since 1900 Lubeck has been in direct communication with the Elbe to Lawenburg by the Elbe-Trave Canal, length 42 miles, width 12 ft. at the bottom and 1o5 to 126 ft. at the top: mini mum depth 86 ft., equipped with 7 locks each 8o m. long, and with a gate width of 12 m. (See Der Bau des Elbe-Trave Canals and seine Vorgeschichte [Lubeck 1900] ; Dr. Emil Hammermann Der Elbe-Trave-Kanal [Jena, Fischer, 1914] .) The Mittelland Canal (see INLAND WATER TRANSPORT), last part (Hanover Magdeburg) of which is now under construction, will establish water communication between the Elbe and Rhine systems.

Traffic.

The traffic on the Elbe cannot rival the Rhine, par ticularly in so far as heavy goods transport is concerned. The principal heavy goods on the Elbe are lignite and potash. The Elbe has not many important tributaries (only Saale and Havel are of some importance). The main sphere of activity for navi gation is therefore the river itself. This fact increases the importance of the transhipment places for the hinterland. It is to be expected that the completion of the Mittelland Canal and of the canalisation of the Saale with canals to Leopoldshall Leipzig, will tend to diminish this importance, particularly with regard to transhipment places on the middle Elbe. The principal commodities in Elbe traffic are potash and other salts, sugar, paper, ore, glass and glassware, raw steel, bauxite, iron pyrites, phosphates, timber, cereals, fertilizers, oils, fats and beer.Before the World War the Elbe carried considerably more goods than the competing railways, the general direction of which is parallel to the river, and this notwithstanding an important num ber of exceptional tariffs for consignments by rail to and from sea ports. Out of Hamburg export by sea of goods from the upper Elbe region 5.2 million arrived by rail; 4.6 million tons by water (47 per cent). Out of Hamburg import of goods for the upper Elbe region 2.6 million tons went by rail, 5.8 million tons (69%) by water. Corresponding figures for the present period are: 1925 (1927): exports, rail 3.9 million tons (5.9), water 3.2 (3.5) or 45% (37%) : imports, rail 3.3 million tons (3.9) water 3.1 (4.6) or 48% (54%) . These figures show that rail compe tition has become important, but it should be observed that whilst the proportion of water-traffic in down-stream direction is still decreasing water-traffic in up-stream direction shows an increase, both absolute and relative. Before the war there were several competing railway systems. Thus the Saxon railways favoured transhipment in Saxon ports by special rates, which to a certain degree counter-balanced the influence of exceptional seaport rates. All exceptional tariffs were abolished during the war. Afterwards the peace treaties prohibited Germany for a time from granting special tariffs either for river or seaports.

After the World War the various German railway systems were amalgamated and there no longer existed an interest for the rail way to favour transhipment in river ports. Moreover in 192o the German railways introduced the system of long distance rebate rates and sometime ago re-established exceptional tariffs for sea ports, but not for river ports. It should be observed also that the falling off in down-stream traffic is also partly due to change in economic conditions, e.g., a considerable decrease in timber floating and in coal exports from Bohemia. Only in 1926 (British coal strike) did the figure for coal exports from Czechoslovakia approach the pre-war figure. In order to meet railway competition the shipping companies formed a combine, which for the greater part of the time only applied to down-stream traffic. The results have been fairly satisfactory, and although the railways captured part of the heavy goods traffic from the waterway the latter were able to secure the transport of certain classes of valuable goods.

Czechoslovakia has a considerable interest in Elbe navigation. For 1926: Out of a total of 6,385 vessels crossing the German Czechoslovak frontier (both directions together) 1,804 sailed under the Czechoslovakian flag. Of all the vessels entering and leaving the ports of Dresden and Riesa to% or over were Czecho slovakian and the proportion of the Czechoslovak flag in the movements of vessels entering or leaving the ports of Hamburg, Harburg and Altona from or to up-stream was over 5%. For the same year the total exports of Czechoslovakia via the Elbe amounted to 1,529,00o tons (550,000 tons of sugar) ; in addition tons of timber were floated. Its total imports via the Elbe for the same period amounted to 556,00o tons.

The total quantity of goods transported on the international river system exceeded 10,400,000 tons, which constitutes an in crease of 2,280,000 tons over the 1925 figures, or 28%. The inter course between the Elbe and the principal waterways connected with it was, for the Saale 369,000 tons, for the Havel about 3 million tons, for the Trave Canal 1,226,000 tons. Generally speak ing river navigation begins and ends in the ports of Hamburg, Harburg and Altona. (For figures giving the despatches and arrivals of goods see below).

Ports.

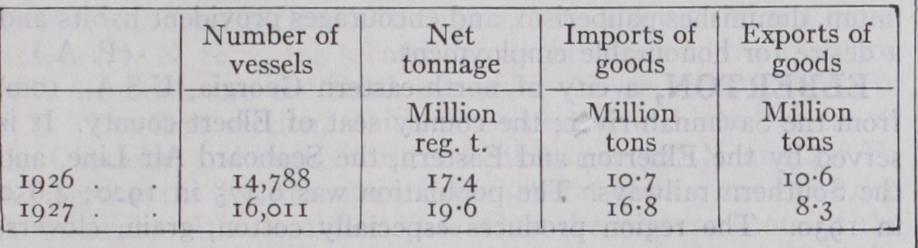

In Czechoslovakia: Holesovic.—Total movement of goods 1926, 158,000 tons, principally traffic in downstream direc tion. Melnik. 255,000 tons, mainly downstream. Usti. 86o,000 tons, increase of 66% over 1925 (British Coal Strike). The tran shipment traffic before the war was over 2 million tons. It fell to 2 million tons after the war, but is now again increasing. Loubi-Decin, 282,00o tons (138,000 less than 1925). These ports used to be very important transhipment places, but have lost a good deal of traffic.In Germany : Dresden.—Besides the important Konig Albert Harbour, there are old and new town quays, and the Prieschner Harbour traffic amounted to 574,000 tons in 1926, showing an increase of almost Ioo,000 tons over the preceding year. Riesa is an important place for transhipment from water to rail, and vice versa. In 1926, traffic in downstream direction amounted to 230, 00o tons, in upstream direction to 423,00o tons. Dessau-Wallwitz, total traffic 318,000 tons. Aken, total traffic 358,000 tons. Schone beck, total traffic 4 7 1 ,000 tons. For the last two ports traffic in downstream direction amounts to 8g% of the total traffic. Magde burg, the most important Elbe port after Hamburg, for 1926 total arrivals of goods, 586,00o tons, total despatches, 575,00o tons. The ports complex of Hamburg, Harburg and Altona show a total of arrivals from upstream of 5,050,00o in 1926 (3,382,00o in 1925) ; total of despatches in upstream direction for the same period, (3,874,000). The port complex of Hamburg is, of course, much more important as a maritime port. In 1913, over 15,00o vessels with a net tonnage of 14.2 million reg. tons, visited the Port of Hamburg; imports amounted to 16.6 million tons; exports to 8.9 million tons net. After the war there was a very considerable fall-off of traffic. In 1919, for instance, only 2,800 vessels (1.6 million reg. tons) called at the Port. Imports and exports together only reached a figure of 2.3 million tons. From then the Port statistics show a constant and important increase of traffic. Already in 1923, the total net tonnage of 1913 is sur passed (15.3 million reg. tons). Imports and exports for the same year amounted to 21 million tons. The figures for the years 1926 and 1927 are: These figures show that the goods traffic reached the pre-war fig ures at the same time. The movement of vessels shows an in crease of i,000 in number and 5.4 million reg. tons. The propor tion of vessels under German flag is now 41.5 % (1913 : 6o%) . For the shipping industry, the present development is far from favourable in comparison with pre-war times, but the increased traffic of vessels is all to the interest of commerce, since the num ber of arrivals and departures of vessels has become much greater. International Regime.—Under Article 331 of the Treaty of Versailles, the Elbe from its confluence with the Vltava (Moldau) was declared international. The administration of its system was entrusted to an International Commission composed of four rep resentatives of the German Riparian States, two of Czechoslo vakia and one each of Great Britain, France, Italy and Belgium. This Commission drew up the Navigation Act signed at Dresden, February 22nd, 1922 (League of Nations Treaty Series, volume XXVI. No. 649, 1924). The Commission has to provide for free dom of navigation and equality of treatment ; to take decisions on complaints arising out of the application of the Act; to see that the navigable waterway is kept in good condition and to supervise improvements. Its jurisdiction may be extended, subject to the unanimous consent of the Commission, by decision of the riparian State or States concerned. A Supplementary Convention signed at Prague, January 27th, 1923, laid down detailed regu lations for navigation tribunals and for appeal. The headquarters of the commission are at Dresden. It holds one or two sessions a year.

Tolls.

In the days of the old German Empire no fewer than 35 different tolls were levied between Melnik and Hamburg, to say nothing of the special dues and privileged exactions of various riparian owners and political authorities. By the Elbe Navigation Act of 1822, concluded between the various riparian States, a definite number of tolls at fixed rates was substituted for the often arbitrary tolls which had been exacted previously. Still further relief was afforded in 1844 and 185o, and in 1863 the number of tolls was reduced to one, levied at Wittenberg. Finally, in 187o, 1,000,00o thalers were paid to Mecklenburg and 85,00o thalers to Anhalt, which thereupon abandoned all claims to levy tolls upon the Elbe shipping, and thus navigation on the river became at last entirely free.A Bill adopted by the Reich in 1911 introduced taxes on navi gation on German waterways with the exception, however, of the international rivers on which taxes had been abolished by interna tional agreement. During the World War Germany established a general tax on transport (Verkehrssteuer) which was also levied on goods transported on the Rhine and the Elbe. Owing to pro tests, however, of foreign Governments concerned this tax was abolished for Rhine and Elbe transport. The new Navigation Act provides that the International Commission may exceptionally and under certain conditions authorise the levying of taxes in order to cover the cost of important works of improvement. The taxes should, however, not be higher than the service rendered. Fish.—The river is well stocked with fish, both salt-water and fresh-water species. Of the many varieties the kinds of greatest economic value are sturgeon, shad, salmon, lampreys, eels, pike and whiting.