Electioneering Tactics

ELECTIONEERING TACTICS The Influencing of Voters.—Though, in practice, many voters cast their votes for candidates they know nothing about, it is rarely the fault of the candidates. It is of the essence of their desire to represent others that they should make clear to their constituents their purposes and character. Indeed, the large number of constituents for each representative in the modern State compels the creation of a machine and methods to impress the others. Representation is unthinkable, under modern social conditions, on any other basis. Candidates have rarely conceived their task as one simply of enlightening the electors. The attitude of a John Stuart Mill or a Macaulay is a rarity. The candidate, and certainly his party followers and workers, as well as his agent, want victory, and this desire too often causes them to adopt tactics which they alone would be likely to confound with en lightening the elector. There is a class of acts—large, not easily definable—which causes undue or unfair influence, making impos sible any rational vote and destroying that elusive entity, the "real will" of the electors. Laws have therefore been made re straining injurious activity, and they can be broadly divided into two classes, those regulating the expenditure at elections, and those defining and creating penalties for corrupt practices.

In Great Britain, the Corrupt and Illegal Practices Act of 1883 codified and added to the piecemeal legislation of previous cen turies, making a code of admirable strictness. Corrupt practices include : (1) Bribery by gift, loan or promise of money or money's worth to vote or abstain from voting; by offer or promise of a situation or employment to a voter or any one connected with him, by giving or paying money for the purpose of bribery, by gift or promise to a third person to procure a vote, or payment for loss of time, wages or travelling expenses to secure a vote; and the consequences are the same whether bribery is committed before, during or after an election. (2) Treating, which means the provision or payment for any person, of meat, drink, enter tainment or provision, at any time, in order to induce him, or any other person to vote or abstain from voting—and such extends to the wives or relatives of voters. (3) Undue influence, i.e., the making use, or the threatening to make use of any force, violence or restraint, or inflicting or threatening to inflict any temporal or spiritual injury on any person in order to influence his vote, or by duress or fraud impeding the free exercise of the franchise by any man. (4) Personation (q.v.) applying for a ballot paper in the name of another person, whether alive or dead, voting twice at the same election, aiding or abetting personation, forging or counterfeiting a ballot paper. (5) Unauthorized expenditure. That expenditure which is not authorized in writing by the elec tion agent. Illegal practices include paid conveyancing, adver tising, and hiring, without authority, committee rooms; voting without qualification ; false statements made about candidates; disturbance of public meetings between the issue of the election writ and the return of the election; printing, publishing or posting any bill, placard or poster not bearing on its face the name and address of the printer and publisher ; illegal proxy voting. Heavy fines and withdrawal of the right to vote or be a candidate are attached to these offences. The expenses of the candidates were limited by the act of 1883 and now, after the passage of the Re form Acts of 1918 and 1928 stand at 5d. per elector in a borough constituency and 6d. per elector in a county constituency.

Nothing, however, has been done to prevent party head quarters giving aid to a candidate as an organization not in his pay and in a general fashion. Poorer candidates and party organ izations have much to complain of, nor can any close observer of elections deny that richer candidates can and do have materially more influence. The conveyance of voters to the poll in hired vehicles is prohibited. But it is a well known fact that candi dates and their agents have found ways and means of driving many a motor car through this clause of the act. Nor are the parties which have a legitimate right to contest an election always ready to do so, for they are restrained by the fear of unpopularity, whether they succeed or not. Thus widely illegal and corrupt practices go unpunished. The dominions have codes of electoral propriety closely resembling that of the Mother Country and offer no conspicuous variations.

Among European countries Hungary, Rumania, Bulgaria and Greece have been pre-eminent in the corruption of their political systems. In the United States three means of corruption have been used : money, public office and serious forms of undue influence. It has been estimated by Prof. Charles Merriam that the two major parties alone in only a presidential campaign spend together some $20,000,000. Money is also freely spent in smaller contests; sums of over $100,000 have been spent on the election of a single person to the Senate. An official enquirer (Senator Kenyon, chairman of the Senate committee on privileges and elections, U.S.A., 1921) was justified in calling these sums "a present and growing menace to the nation," even when allow ance is made for the wide tracts of land to be covered in the United States in an election campaign. Besides money the party leaders had as election currency thousands of Federal, State and local offices in their gifts, but these, since 1883, are being gradu ally withdrawn from the "spoils" system. From the office-holders on the "spoils" system collections of a percentage of their salaries were made for the party funds ; but these assessments are now in the process of extinction. Since 1890 many laws have sought to regulate electoral sincerity, and they have concentrated upon publicity of the source and destination of campaign funds, have sought to secure reports of personal service; some States (e.g., Alabama, Kentucky, Minnesota, New Jersey, Wisconsin and sev eral others), even going so far as to require accounts and reports several days prior to the election. The laws have gone a long way towards defining and enumerating legitimate expenditure and ille gitimate means of influence. Some States (Alabama, Minnesota, Massachusetts and Wisconsin), require that all political adver tisements shall be signed and marked "Paid advertisement," stat ing the price paid, the advertiser and the author. In the three latter States and Kansas the purchase of newspaper support is forbidden. These laws have done much good. While party man agers have not been wholly restrained from that class of immoral electoral behaviour now prohibited by statute, their task has been made more difficult to a point which has forced many to become honest. One contribution of American practice to electoral pro cedure is the introduction of the Publicity Pamphlet. Oregon in 1908 passed a law requiring all candidates to take at fixed rates from one to four pages of a pamphlet published and sent to all voters by the secretary of State. Persons desiring to oppose can didates may also take space for that purpose, providing due notice is given to the person attacked and subject to the law of libel. Several other States have adopted this system, but it has worked best in its native State. On the whole these publicity pamphlets have no more value than assembled copies of the English election addresses which are printed by the candidates, and one mail of which may be sent to parliamentary electors at the State's expense.

French law on corrupt practices was codified in the decree of Feb. 1852, but little heed was taken of its provisions until the laws of July 29, 1913, and March 31, 1914, redefined the offences and created severe penalties. A light is thrown upon French elec toral procedure when we remark that in the latter statute Govern ment pressure is expressly condemned.

It is always necessary to remember that there is much "in fluence" which is impalpable but very effective—not usually ex ercised wholesale, but in the form of individual pressure, difficult to detect or to resist. A shopkeeper, for example, may fear to express his opinions by exhibiting the placard he favours; a police man may be taken off his guard by a popular local politician, and other known party workers may be victimized in a way which, to the outer eye, appears economically fair. In the Southern States of the United States the negro problem has found a partial solu tion in variously devised qualifications for the vote, but one must add to the total means of racial discrimination the opinion of the white neighbourhood, which may at any time be supported by injustices done in the law courts, rough handling and even lynching.

Recent electoral proceedings in the more populous countries, such as France, Germany and Great Britain have shown two characteristics of much importance. The first is the increased rowdiness at election meetings. This is undoubtedly due to what may be called the maturity of the franchise. The vote has been given to practically all adults, and these have been simultaneously persuaded that the political struggle may give wealth and power to some and take it from others. Intolerance is bound to be the consequence of such a conviction, and it issues in the attempt to stop opponents from stating their case. The second is the use of the microphone for broadcasting speeches. While in the United States this form of political speaking was effectively used by both leading candidates in the 1928 presidential election, it has not reached its full development in other countries, Majority and Minority Representation.—Three systems of representation are at present operative. There are countries like Great Britain and most of the States of the United States of America, where however many candidates stand for a single available seat the one candidate who tops the list by however little over the next below him is elected. This is called the plurality majority system, and it is not difficult to see that since all the unsuccessful candidates may have between them more than 5o% of the votes cast, the majority may be unrepresented. In order to avoid such inequity two principal methods have been invented: the second ballot, as operative in France and other European countries who have no proportional representation system, and the alternative vote. In the former, where no candidate obtains an absolute majority, i.e., anything over . o% of the total votes cast, a second ballot takes place, in which all unsuccessful candidates are at once or progressively excluded, an absolute decision between the two candidates finally remaining being ultimately arrived at. The alternative vote is the method which secures the benefits of the second ballot at a single election, the voter marking the candi dates on his ballot paper with a series of preferences 1, 2, 3 and so on—whence the method is sometimes called the preferential vote. This is much used in Australia. Many countries, notably Belgium, Holland and Germany have adopted a system of pro portional representation, that is, methods of casting and counting ballots which allow of a representation of political opinion in fairly strict proportional representation. The respective merits and demerits of these systems are dealt with in the article on PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION.

Delegate and Representative.

Once the candidate has suc ceeded in getting elected, is he to act upon instructions and primarily for the constituency, or to use his discretion broadly for the welfare of the whole country? Until recent years the generally accepted view was that the elected person is a repre sentative and has no particular mandate. This theory was embodied in France in the Constitution of Sept. 3, 1791 (sec. 3, art. 7) : "The representatives chosen in the departments shall not be representatives of a particular department, but of the entire nation, and no one may give them any instructions (mandat)." The theory and even the words of the article have been copied by most countries since in their written Constitu tions. In England much the same theory was enunciated by Edmund Burke in his speech to the sheriffs of Bristol (1780), but with less abstract dogmatism. The 19th century has witnessed the triumph of the French view over new forms of political organization. The prime movers in political life became political parties, propagandist organizations and organized economic groups like trade unions. They demand an adherence not to their strict instructions, but to their general principles, and it is a general, though not a legal rule, that the member who finds himself in plain disagreement with his supporting group must explain the grounds of his divergence. In Europe, outside Russia, it is gen erally recognized that the member cannot do his best work without a certain amount of independence. On the whole, Burke's view is accepted : "Look, gentlemen, to the whole tenor of your member's conduct. . . . He may have fallen into errors : he must have faults; but our error is greater and our fault is radically ruinous to ourselves if we do not bear, if we do not even applaud, the whole compound and mixed mass of such a char acter . . . if by a fair, by an indulgent, by a gentlemanly behaviour to our representatives, we do not give confidence to their minds, and a liberal scope to their understandings; if we do not permit our members to act upon a very enlarged view of things, we shall at length infallibly degrade our national repre sentation into a confused and shuffling bustle of local agency." It is, indeed, a nice balance which has to be kept. But the claims of the organized electors have received greater validity in Russia than elsewhere. There, quite plainly, the mandate of the whole people is denied, and the system of the definite and imperative mandate has been adopted. By the Constitution of 1925 (art. 63, and the previous Constitution of 1918), the members of the soviets are obliged to report regularly to their electors on their action, and art. 75 gives the electors the right to revoke their mandate at any time and elect another member. The congresses have reiterated this right and power and urged its employment. About a dozen States in the United States have the system of the recall for controlling the activity of members both of the legislative and of the administration. It is actually used chiefly against local officials and arouses intense electoral interest.

Non-voting and Compulsory Voting.

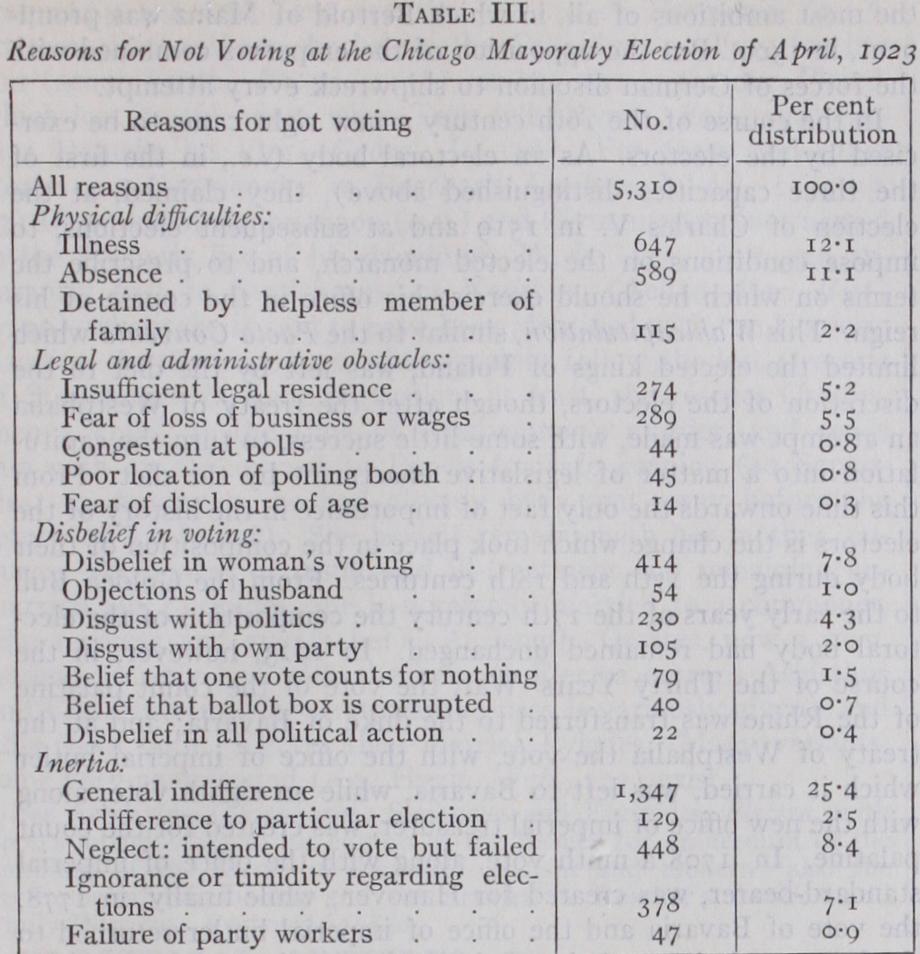

A disturbing phe nomenon in all electoral systems is the small percentage of actual voters. In England the parliamentary vote is normally about 70% of its full strength; in France it is not much over 6o%, in Ger many it is often over 75%, and in the United States, where the word "non-voting" was invented, presidential elections have had as great a proportion as 8o% voting; but in other elections, State and local, there is a great falling off. The best extant study of non-voting is that by Prof. H. Gosnell of Chicago university, who found by actual research the following causes in the degree expressed in Table III., p. We cannot say how far the percentages fit conditions outside Chicago for that particular election, but the causes of non-voting as analyzed and defined in this study are useful clues. Non voting has caused considerable anxiety to the supporters of democracy and it is natural that reformers should have hit upon the idea of compulsory voting. Switzerland, Spain, Argentine, Bulgaria, Austria, New Zealand, Czechoslovakia, Holland and Belgium have penalties for non-voters--all of them with the exception of Holland and Czechoslovakia dating from before the war. The Australian Commonwealth adopted a system in 1924. Belgium, which has enforced its law most stringently, began to compel voters as early as 1893 with the penalty of a fine of from one to three francs or a reprimand for the first omission to vote; for a second omission within six years a fine of from three to 25 francs ; for a third omission within ten years a similar penalty and the exhibition of the offender's name on a placard outside the town hall for a month. The fourth omission in 15 years brings about a more serious punishment : similar fines and the removal of the elector's name from the register for ten years, during which time he may receive from the State no promotion, distinction or nomi nation to public office in local or central Government. Though the franchise has been greatly widened since 1893 the abstentions have never been higher than 7.5% (in 1896) and in 190o were 6%, and in 1912 only 4%. Altogether, from 1899-1912 it needed 24,819 convictions of various degrees (about 1o,000 being repri mands) to secure this result. The main question is : is it worth while spending the energy and money required to make voters exercise the vote? Is the vote, as some consider it, a right, or as others, a civic duty? (H. FL)