Electoral Systems

ELECTORAL SYSTEMS. To elect is to choose, and in the sense of the present discussion, an electoral system is a means of choice of members of a governmental organization—a term used in preference to the word state, to emphasize the concrete nature of the purpose served by an electoral system. Political theorists and practical politicians can be ranged into two great schools of thought ; those who look upon systems of election absolutely as equitable expressions of the sovereignty of the people ; and those who, accepting the sovereignty of the people and the representative principle, yet regard the system of election pragmatically, as an instrument of government in which absolute equity must not seldom retreat before the pressing need for gov ernment. On every occasion of the modification of the franchise in regard to age and sex, or in the controversies about proportional representation, or in the matter of compulsory voting, this differ ence of attitude is apparent.

The electoral system is, then, part of the machinery of govern ment, and the part it plays varies from country to country in accordance with the political system. The number of elective offices may be very large, as in the United States at the present time, or very small, as in Germany before the advent of repre sentative institutions. Or it may, as in most democratic countries, be confined to the legislative assemblies of central and local government. We confine our attention to the central representa tive assembly, in particular to the lower house, though what we have to say applies almost in every detail to municipal elections. The significance of these electoral systems is determined by the extent to which the sovereignty of the people is admitted by the Constitution, but the mere declaration of such sovereignty either in the written Constitution or in the conventional opinion of the day must not be taken as a measure of the role of election. One must look to all the other institutions which compose the State: the power of a House of Lords, in Great Britain; presidential powers, as in America, France and Germany, royal power in coun tries with a constitutional monarchical system. It would be idle, too, after the electoral experience of the last half-century wher ever representative institutions have been created, to judge the electoral systems upon their literary form. Every election is a time of intense, though underground pressure of interests, social and economic, in more or less organized form, disturbing consti tutional symmetry and abrogating its equity. Threats, intimida tion, terrorization and victimization of the most diverse kinds become operative, and in their obvious and indiscreet forms are forbidden by law everywhere. But the economic power of an employer in an industrial country, or a landed proprietor in an agricultural country under modern productive methods is subtle, pervasive and legally unregulated.

Thus, of electoral systems in general we may say that their real meaning depends upon their ultimate governmental effective ness, their relationship to other political institutions and the social system within which they operate. In considering the subject, then, we ought not to confine our examination to the written text of the franchise acts alone, but must consider an electoral sys tem broadly, as all those means whereby a person becomes a mem ber of an elected assembly, and narrowly, as those means which are sanctioned by the laws. Of ancient practice some account will be found in the article on voting. (See VOTE and VOTING.) In modern practice the topics which must be discussed are :—(a) candidature; (b) returning officer; (c) the franchise : qualifica tions and disqualifications; (d) election day; (e) ballot; (f) ex penses and the canvassing of voters; (g) representative or dele gate; (li) non-voting and compulsory voting.

Candidature.

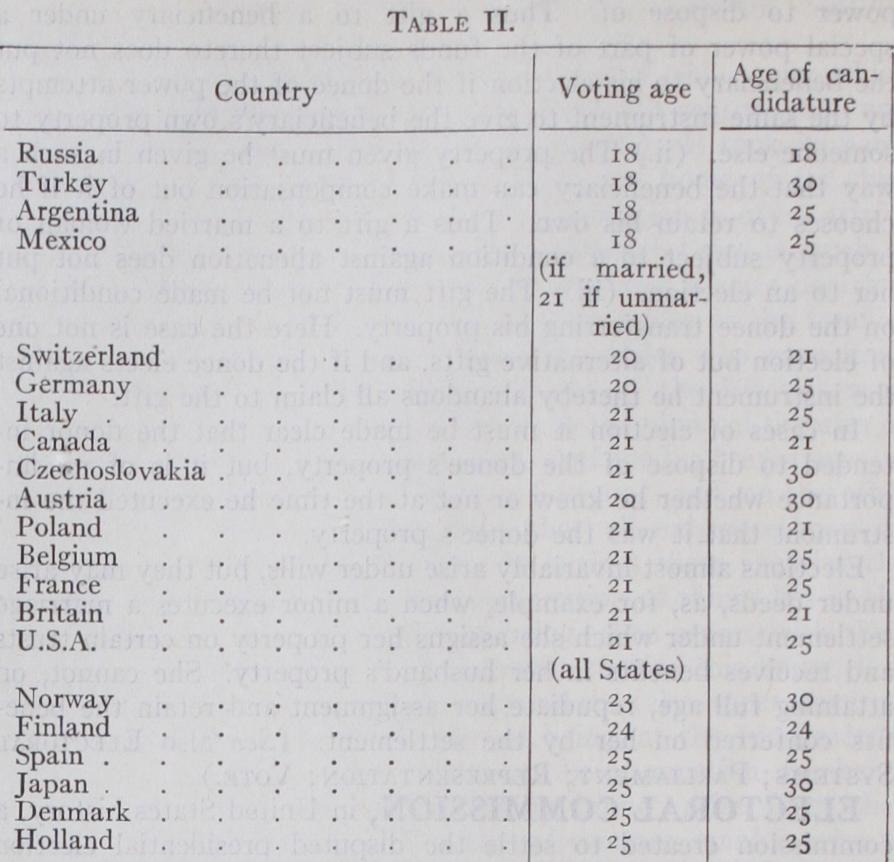

The democratic development of the i 9th cen tury and of our own day has generally brought about (1) ease and freedom of candidature, and (2) an approximation of the age limit of candidature to that for the exercise of the vote.As regards freedom of candidature, the tendency has been to avoid the interference of the State in the electors' choice of can didates, and to restrict the action of the State to providing that ineligibility shall be determined after the election by a tribunal likely to be impartial. Such tribunals are parliamentary as in the United States Federal authority, in Norway, the Netherlands and Belgium or extra-parliamentary as in Great Britain, the Australian Commonwealth and Germany. But statesmen have been un willing to allow a perfect freedom of candidature, and have sought to secure an element of electoral responsibility by requiring a candidate to be sponsored by a number of electors who sign a nomination form. The number thus required differs very much. For example :- The age of candidature and its present approximation to age for the right to vote is observable from table II. (lower house only) .

But not all countries now accept the freedom of candidature. Indeed, one of the most remarkable phenomena of modern gov ernment is the extent to which the tenets of 19th century democ racy have been challenged in this respect. The counter action comes from two quarters: the United States, and Italy and Russia; the source in the first-named country is the excesses of democracy brought about partly by the type of people who are politically active, and partly by the social environment; in the latter it is the plain denial of the political validity of democratic electoral systems.

In the United States, as in Great Britain, the British dominions and Europe, the electoral systems were established on the basis of the "natural" rights of the individual. The individual thus envisaged was regarded as an independent, self-sufficient, freely acting entity, without social or economic relationships, except those which originated in his self-interest, and which were created by his private activity, unaided and unimpeded by the State. Thence naturally followed freedom of candidature and the uni versal franchise. But men do not act as independent atoms, and three-quarters of the way through the 19th century nothing was more striking than the enormous power and indispensable services exercised by political parties in organizing the enfranchised atoms; nor could one mistake the growing significance to men of the sense of State and its activities and institutions, or the grouping of men in vocations. The 19th century State relied exclusively upon political parties for the choice of candidates and even, in many countries, for other electoral services, like the distribution of ballot papers. But while the State was thus periodically created, dissolved and recreated by party activity, it is amazing that this process went on in a fit of statutory absent-mindedness. The State certainly, did not seek to regulate the activity of parties in their choice of candidates, and with the exception of the countries we are about to discuss does not do so now.

The States of the United States of America were the first to suffer from this blithe unconsciousness. The large number of offices filled by election, the enormous territorial range of the country, and the popular preoccupation with economic activity, necessitated strong party organizations. Into the hands of their "bosses" fell the nomination of candidates. They looked upon the nominations as commodities saleable to individuals and companies and excluded voters from the nominating conventions by various devices; conventions were held without due notice and in out of-the-way places; they were "packed" with hooligans, electoral lists were "padded" and ballot boxes "stuffed." A reaction set in in the '8os, and the States (California commenced as early as 1866) began to regulate the method of nomination. Legisla tion, at first permissive, became compulsory, and more and more offices were included. In primary conventions for the presidency were added. All States, save three or four, have now established principles and methods for regulating the nomina tion of candidates through the party machinery. This involves rules (1) to decide which are the parties entitled to nominate, and this is settled variously by the number of votes returned at the preceding election or, more frequently, by a fixed proportion of the votes cast, and these range from 2% to 2 5 % of the entire vote; (2) to define those who are entitled to appear at the nomi nating primaries, that is to define party membership, and this is done by a special enrolment in the party, by secret or open process, some time before the elections; by declaration by ballot when actually at the primary; by decision of the party officials (this in the southern States, where the problem of negro fran chise gives trouble) ; and the Wisconsin method, whereby the voter at the primary votes for the candidate he desires on a ballot paper of his special party colour, which he secretly detaches from a perforated pad of ballot papers, each of which represents a Jif f erent party; (3) the time, place, method of voting and counting are legally regulated.

One question still remains to be solved; how can a citizen get his name placed on the nomination paper at the primary elections? This leads back to the ultimate problem. The methods laid down by the States vary. One method is that of petition which must be signed by a fixed number or an agreed percentage of the voters. This is a very expensive method. In another the party committee nominates long before the election and dissentient elements may by petition present others. One other problem arises : what vote at the primary election constitutes an effective choice of a candi date? Some States require an absolute majority, secured in some places by the second ballot and in others by the alternative vote system; others require at least 3 5 % of the votes to be obtained for a nomination, and if the primary does not secure this, a party convention is called. In Oregon statutory arrangements, at State expense, have been made to give the candidates for candidacy an opportunity of writing their views in a pamphlet printed and cir culated by the State.

This system has not notably improved the American electoral systems. The politically conscious electors are still in control of the machine, but the cruder forms of corruption have disappeared. Wirepulling has by no means ceased ; it is simply driven back one stage further to the pre-primary arrangements. For the ordinary citizen electioneering has been complicated and the possibility of a clear view of electoral responsibility diminished. Expenses have been increased. Popular interest in the nominations has slightly increased; but nothing can effect a radical change of electoral manners save a change of popular outlook and education.

Another peculiarity of the choice of candidates in the United States is that candidates are by law and custom required to be inhabitants of the State in which they stand. Some States go further and demand that the candidate shall be a resident of the district which he seeks to represent. Many intelligent Ameri can observers are agreed that this restriction of choice is seriously detrimental to the quality of American legislatures.

No greater contrast could be presented to the recent develop ments in the United States than those in Italy and Russia. Italy since 1922 and Russia since 1918 rest upon a political basis which totally denies the individual's right to freedom. Fascism starts out with the whole nation as the unit of State life, and within that unity recognizes the personality of corporations, economic and social, but only as integral elements of the State. The individual has electoral significance in his proper corporation, and the cor poration in the State, and it is positively denied that all individ uals and all corporations are electorally equal and free. Since 1922 Italian legislation has abolished the democratic electoral system. First (in Nov. 1923) all Fascist candidates were chosen by a central committee for nominations, the list being revised by Mussolini and then, in May 1928, the corporative State having been created by the Fascist regime, a new system was set up. Various corporations were to nominate goo candidates, the Fascist Grand Council to choose from these some 40o candidates, and these 40o candidates to be put before the electors for approval en bloc. (See also FASCISM : Though the policy of the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics (U.S.S.R.) is much different from the Fascist system, the elec toral system is similarly converted to the use of a special organiza tion working within a system which asserts the priority of the State over groups and individuals. The right of nomination as candidates for the Soviet is given to parties, professional organi zations, military units, workshops and other vocational units. All this seems to favour a freedom of nomination so long as such nomination issues from a recognized "productive" group. But the Communist Party is all-powerful, and is made so by various de jure privileges and its de facto capacity to extirpate opposi tion. Candidature is thus not free in practice.

Candidature may always be taken as a safe guide to the real nature of the political system under discussion. Though we have characterized the systems of Europe as, in general, free, we mean free of legal interference, save for the rules with respect to age, nationality and so on. Systems can therefore be graded from the minimum to the maximum of State interference as in the United States, Italy and Russia; but the intentions of those who have interfered are poles asunder. In the countries where there is little or no legislative interference with nomination, there are still local party caucuses who set their own terms for nomination wealth, beauty, social status, electoral cleverness, even intellect. These caucuses have a great amount of power, though the law has not given it to them; they are representatives of the Idea, and control and organize the money and the workers for the Idea. Where party organization is strong, as in the Anglo-Saxon coun tries, the party is the deciding factor in the choice of candidates, though this does not mean the central authority of the party. In the Latin countries and in the Balkans, party organization is still too weak to regard such a monopoly as a safe one, and small evanescent groups nominate. In Germany, since the elections to the constituent assembly in 1919, the peculiar nature of its system of proportional representation has made the party ma chine dominant in the choice of candidates, for the party head quarters wishes to count upon safe seats for certain men and is able to offer safe seats to others out of its national fund of votes accumulated from the votes of unsuccessful candidates at the elec tions. It can be taken as a fair generalization that, wherever the system of "P.R." operates with what is known as a "list sys tem," the party machine and central control within the party ma chine has the nominating power strongly in its hands.