Electric Furnaces

ELECTRIC FURNACES. All electric furnaces depend for their operation on the fact that when electricity passes along any path a certain proportion of the electrical energy is converted into heat energy. The amount so converted is directly proportional to the resistance offered by the path traversed by the electrical energy.

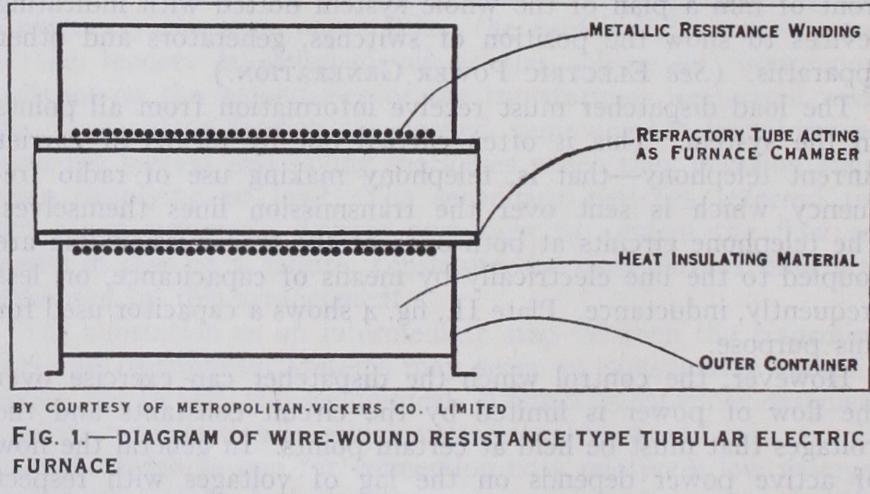

One of the simplest forms of electric furnace is the resistance type furnace in which heat is generated by the passage of elec tricity through a conductor of a resistance designed so as to ensure the conversion to heat of the required amount of energy. Furnaces of this type may depend upon either metallic conduc tors or non-metallic conductors. Of metallic conductors the most widely used are nickel-chromium alloys; platinum, molybdenum and tungsten, are used to a lesser extent, the choice of conductor depending on the temperature at which is required to operate the furnace. For temperatures up to 1,000° C, nickel-chromium is used, but for higher temperatures the other metals mentioned above must be employed. If molybdenum or tungsten be used it is necessary that these should be operated in an atmosphere from which oxygen is excluded, the normal method of employing these materials being to use them in a furnace through which a con stant stream of hydrogen is passed. Using wire-wound furnaces of this type, temperatures of at least 1,600° C may be attained. In cases where it is not possible to exclude oxygen, platinum may be used for temperatures up to about 1,400° C, the disadvantage of platinum being its high cost. For laboratory type furnaces the conductor is usually arranged in the form of a wire or tape winding on a tube of refractory material, the whole being enclosed in an outer case filled with some heat-insulating material. Care has to be taken that the refractory and heat-insulating materials in contact with the winding are also electrical insulators. Indus trial furnaces of this type usually comprise a furnace chamber built of firebrick, strengthened on the outside by metal frame work and fitted on the inside with insulating supports, upon which the wire or tape is wound. Furnaces of this type are used for the heat treatment of steel and general industrial purposes. Up to the present, the only metallic winding used for furnaces exposed to the atmosphere has been a nickel-chromium alloy. Where higher temperatures have been desired and the use of hydrogen, nitrogen, steam and various other atmospheres has been possible, iron tape resistances have been used. Inasmuch as with a furnace of the resistance type the whole of the electrical energy used is converted to heat, it is essential in order to obtain a high overall efficiency, that good thermal insulation should be employed.

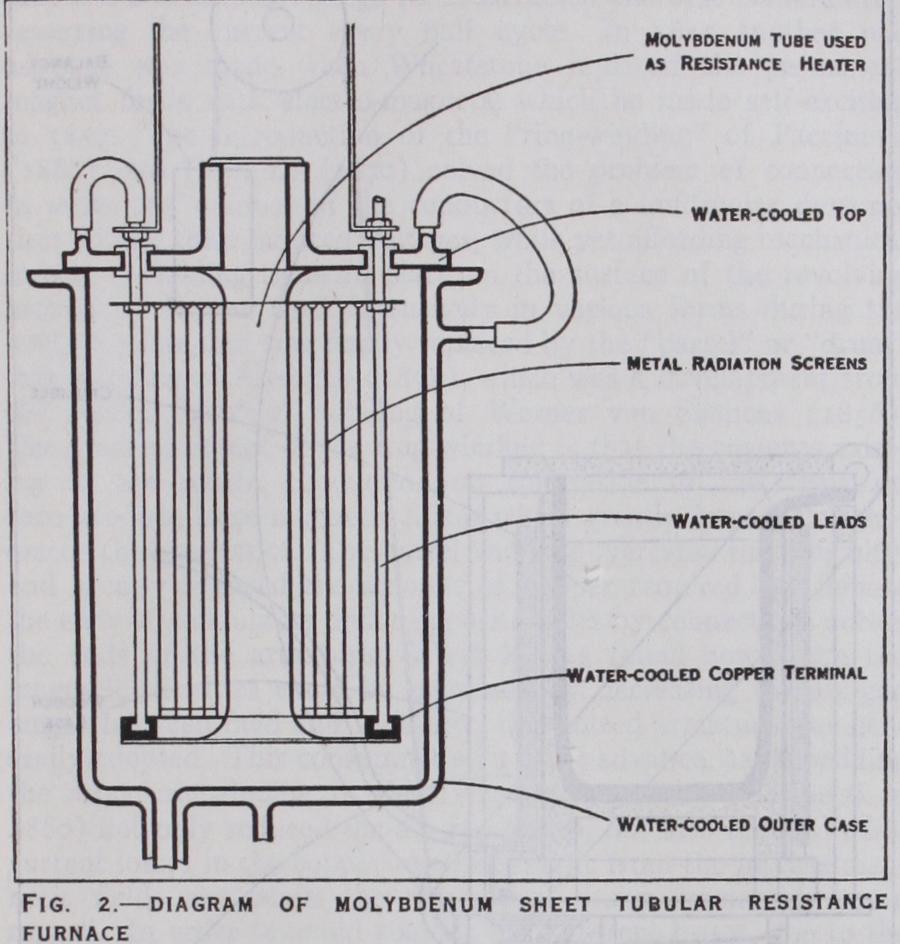

Still higher temperatures may be obtained by using a high melting point metal in the form of sheet. The reason for this is the difficulty experienced in obtaining refractory materials which are insulators at temperatures of 1,600° C or over, and which do not at this temperature react with the metal through which current is passing. By using metal sheet it is possible to avoid the use of any insulating material, although it necessitates a radical alteration in the design of the furnace. An example of a furnace of this type is one in which a tube of molybdenum sheet functions as the heating element and as the wall of the furnace chamber. It is surrounded by concentric tubes of gradually increasing diameter, the whole being enclosed in a water-cooled copper jacket, the furnace having water-cooled leads and top. It is necessary to exhaust the furnace to an X-ray vacuum before raising its tem perature, for two reasons. The first is the necessity for having present no gas which can react with the metal, and the second is due to the fact that no conduction of heat either directly or by convection, may occur through a gaseous medium. The outer con centric tubes then act as radiation shields. The disadvantage is that the resistance of the inner tube which functions as the heating element is very low, so that a very low voltage and a very large current must be used, necessitating the use of a special trans former in order to operate the furnace. Its advantage is that by using molybdenum, temperatures of the order of 2,000° C may be attained quickly, owing to the small heat capacity of the furnace.

The earliest types of resistance furnace employing non-metallic resistances normally consisted of two concentric tubes of electrical insulating refractory material; the space between them was filled with carbon granules or powder, through which a low voltage heavy current was passed. They had the disadvantage that their resistance was very uncertain. Another type of furnace employed a carbon resistor in the form of a helix machined from a graphite tube, but these had to be operated under special conditions, as for example, a vacuum or a non-oxidising atmosphere, in order that the carbon might not be oxidised.

Of recent years, various non-metallic resistors in the shape of rods have been developed and utilised. These chiefly consist of a mixture of carborundum and some suitable binding material.

Furnaces have been constructed and operated utilizing these as resistance elements fixed on insulating supports attached to the inner walls. Such furnaces are used mostly for temperatures be tween 800° C and 1,200° C. The chief disadvantage of elements of this type is the gradual change in resistance which occurs as the life of the element increases, this increase of resistance in some cases being of the order of 10o per cent. The latest type of non metallic resistor to appear by 1928 was in the form of a flat bar consisting of some carbonaceous material, together with a binder, which has been fired at a high temperature and then glazed with an inert refractory. The main industrial application of these up till then had been for the ceramic industry. The furnaces de veloped in this connection have been regenerative tunnel kilns in which the heating elements are placed in the centre of a long tun nel, the ware being passed through continuously at a speed ap propriate to the temperatures which it is desired to attain. Two such kilns are placed in close juxtaposition, the ware being passed in opposite directions in the two kilns so that the hot ware leaving each kiln gives up a large portion of its heat to the cold ware entering the other.

One specialised form of electric resistance furnace is the Wild Barfield furnace for the heat treatment of steels. The temperature to which certain steels have to be heated for treatment coincides with the temperature at which they become non-magnetic. This fact is utilised to make the furnace automatic.

Arc Furnaces.

The first electrical furnaces were arc furnaces In which attempts were made to use the high local heat generated by the arc. Rapid progress was made with these furnaces which are now soundly established in industry. Although in detail they vary greatly, in principle they conform to three main types. In the first type electrodes are inserted through either the walls or the roof, the arc or arcs being formed between the electrodes. The whole is above the metal contained in the furnace hearth, the heat transfer being effected almost entirely by radiation. As this is not direct heating, the thermal efficiency of this type of furnace is not as high as is desirable. In some types an attempt to increase this thermal efficiency is made by directing an arc electromagnetically down against the contents of the furnace. This type of furnace has, however, been almost entirely super seded by other types in which the electrodes are inserted through the roof of the furnace and current passed from them to the metal. In some cases the current passes from one electrode to the metal, through the metal and then to the other electrode or electrodes, depending upon whether one, two or three phase supply is being used. In other furnaces an electrode is inserted in the bottom of the furnace, this electrode carrying part of the current from the metal. The advantages claimed for this latter type of furnace are that short arcs may be used, giv ing a higher thermal efficiency, inasmuch as the arc is brought into closer contact with the metal.On the other hand a disadvantage is the high local temperature attained at the surface of the metal, where the arc strikes it.

This high local temperature is very objectionable when volatile metals are being melted. Furnaces have been constructed up to 40 tons capacity and can be used either for melting cold scrap or for the refining of the molten steel. They are used chiefly for the production of high grade steels. Carbon electrodes are used, these being gradually consumed, much of the carbon passing into the molten metal, a disadvantage when alloys with a low carbon content are required. The furnaces are almost invariably made to tilt.

Another type of arc furnace is one in which the electrodes dip into a bath of a molten salt, the current operating in two ways. The passage of the current from one electrode through the molten salt to the other electrode gives a resistance heating effect keep ing the bath molten, whilst the electrolytic action of the current decomposes the salt giving a deposit of metal on one electrode. This is the process used in the production of aluminium from bauxite.

Induction Furnaces.

Furnaces of the induction type depend essentially for their operation upon resistance heating. Although there is no direct electrical connection between the electrical sup ply and the metal in the bath in a furnace of the induction type, there is an indirect connection by electrical induction. They may be broadly classed into two groups, the cored induction furnace and the coreless induction furnace. The cored induction furnace for steel consists of an annular, ring-shaped bath which acts as the secondary winding of a transformer. The transformer core is a closed iron circuit, the ring-shaped bath and the primary winding being round one leg of this. The furnaces so constructed are normally arranged to tilt, and from the purely electrical stand point are very efficient.For brass melting, a furnace of this type, but so arranged as to have a reservoir of metal above the ring, is known as the Ajax Wyatt type. These furnaces have the disadvantage that a con tinuous ring of metal is necessary in the trough. They must be started by pouring in molten metal and this reduces the flexibility of the furnace from the standpoint of melting alloys of different compositions. Furthermore, there is always a danger of the metal cracking the lining if it is allowed to solidify in the ring part of the furnace.

The ring type furnace for steel making has been somewhat superseded by other types, but for brass melting the core type furnace with a metal reservoir is both efficient and satisfactory. Should continuous operation not be maintained the efficiency of the furnace is seriously impaired. Owing to the action of the electromagnetic field, forces are brought into play which tend to contract the cross section of the metal to such an extent that if the current be large enough the column of liquid metal in the trough may be broken. This effect, of course, varies with the specific gravity of the metal and is much more serious for the light than for the heavy metals.

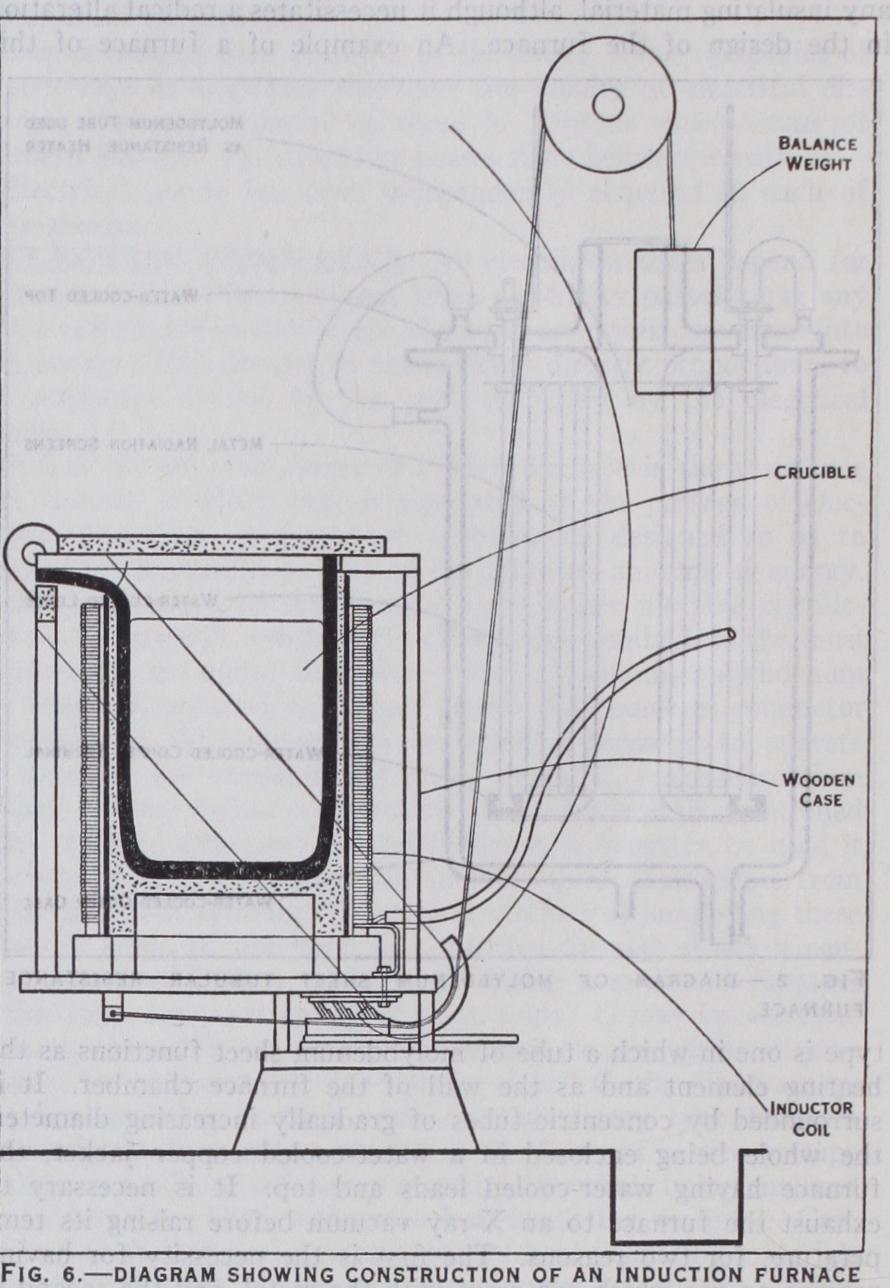

Many difficulties are eliminated by the introduction of the core less induction furnace, known as the Ajax Northrup High Fre quency Furnace, as this permits the use of a standard crucible and removes the necessity for a ring type bath and continuously molten charge. In this furnace the metal to be melted is con tained in a crucible, which in turn is surrounded by a water-cooled coil through which the supply current is passed. It has been known for some time that if a very high frequency current be passed round a coil such as described, the metal in the bath would have eddy currents induced in it, which, provided conditions were right, would generate sufficient heat to melt the charge. It has recently been discovered that for a melt of given resistivity, the minimum frequency which is necessary in order to melt a charge in such a furnace is dependent on the diameter of the charge to be melted. For example, with a crucible 15" in diameter, it is possible to melt steel using a 5°o-cycle supply, whereas in the same cru cible it is possible to melt brass using a supply with a periodicity of 5o alternations per second. As these periodicities can easily be obtained by the use of rotating machinery, furnaces operating on this principle are of commercial utility.

The induction furnace has the advantage that the melting time can be reduced to a very short period. Very thorough mixing of the charge is obtained and it can be kept free from any contami nation from outside sources. This property is one which is of especial value when it is required to produce carbon-free alloys. Accurate control of the temperature is simple and there is no necessity for keeping a minimum of metal in the bath continuously molten. The furnace can easily be adapted to take any type of charge, whilst the fact that the heat is generated in the charge itself means a low metal loss due to evaporation.