Electrical

ELECTRICAL (or ELECTROSTATIC) MACHINE, a ma chine operating by manual or other power for transforming mechanical work into electric energy by the separation of electro static charges of opposite sign delivered to separate conductors. Electrostatic machines are of two kinds : Frictional, and Influence.

Frictional Machines.

A primitive form of frictional elec trical machine was constructed about 1663 by Otto von Guericke (1602-1686). It consisted of a globe of sulphur fixed on an axis and rotated by a winch, and it was electrically excited by the friction of warm hands held against it. Sir Isaac Newton appears to have been the first to use a glass globe instead of sulphur (Optics, 8th Query) . F. Hawksbee in 1709 also used a revolving glass globe. A metal chain resting on the globe served to collect the charge. Later G. M. Bose (1 710-1761), of Wittenberg, added the prime conductor, an insulated tube or cylinder supported on silk strings, and J. H. Winkler (1703-1770), professor of physics at Leipzig, substituted a leather cushion for the hand. Andreas Gordon (1712-1751) of Erfurt, a Scotch Benedictine monk, first used a glass cylinder in place of a sphere. Jesse Ramsden 0735-1800) in 1768 constructed his well known form of plate electrical machine (fig. I ). A glass plate fixed to a wooden or metal shaft is rotated by a winch. It passes between two rubbers made of leather, and is partly covered with two silk aprons which extend over quadrants of its surface.Just below the places where the aprons terminate, the glass is embraced by two insulated metal forks having the sharp points projecting towards the glass, but not quite touching it. The glass is ex cited positively by friction with the rub bers, and the charge is drawn off by the action of the points which, when acted upon inductively, discharge negative electricity against it. The insulated conductor to which the points are connected there fore becomes positively electrified. The cushions must be con nected to earth to remove the negative electricity which accumu lates on them. It was found that the machine acted better if the rubbers were covered with bisulphide of tin or with F. von Kienmayer's amalgam, consisting of one part of zinc, one of tin and two of mercury. The cushions were greased and the amalgam in a state of powder spread over them. Edward Nairne's electrical machine (1787) consisted of a glass cylinder with two insulated conductors, called prime conductors, on glass legs placed near it. One of these carried the leather exacting cushions and the other the collecting metal points, a silk apron extending over the cylinder from the cushion almost to the points. The rubber was smeared with amalgam. The function of the apron is to prevent the escape of electrification from the glass during its passage from the rubber to the collecting points. Nairne's machine could give either positive or negative electricity, the first named being collected from the prime conductor carry ing the collecting points and the second from the prime conductor carrying the cushion.

Influence Machines.

Frictional machines are, however, now quite superseded by the second class of instrument mentioned below, namely, influence machines. These operate by static induction and convert mechanical work into electrostatic energy by the aid of a small initial charge which is subsequently replenished or reinforced in an accumulative manner. The general principle of all the machines described below will be best stood by considering a simple ideal case. Imagine two Leyden jars with large brass knobs, A and B, to stand on the ground (fig. 2). Let one jar be initially charged with positive electricity on its inner coating and the other with negative, and let both have their outsides connected to earth. Imagine two insulated balls A' and B' so held that A' is near A and B' is near B. Then the positive charge on A induces two charges on A', viz. : a tive on the side nearer and a positive on the side more remote. Likewise the negative charge on B induces a positive charge on the side of B' nearer to it and repels negative electricity to the far side. Next let the balls A' and B' be connected together for a moment by a wire N called a neutralizing conductor which is subsequently removed. Then A' will be left negatively electrified and B' will be left positively electrified. Suppose that A' and B' are then made to change places. To do this we shall have to exert energy to remove A' against the attraction of A and B' against the attraction of B. Finally let A' be brought in contact with B and B' with A. The ball A' will give up its charge of negative electricity to the Leyden jar B, and the ball B' will give up its positive charge to the Leyden jar A. This transfer will take place because the inner coatings of the Leyden jars have greater capacity with respect to the earth than the balls. Hence the charges of the jars will be increased. The balls A' and B' are then practically discharged, and the above cycle of operations may be repeated. Hence, however small may be the initial charges of the Leyden jars, by a principle of accumulation re sembling that of compound interest, they can be increased as above shown to any degree or, at least, until the losses due to in complete insulation do not outweigh the gain of charge of either conductor in the same time. If this series of operations be made to depend upon the continuous rotation of a winch or handle, the arrangement constitutes an electrostatic influence machine. The principle therefore somewhat resembles that of the self exciting dynamo.Bennet's Doubler—The first suggestion for a machine of the above kind seems to have grown out of the invention of Volta's electrophorus. Abraham Bennet, the inventor of the gold leaf electroscope, described a doubler or machine for multiplying electric charges (Phil. Trans., 1787).

The principle of this apparatus may be explained thus. Let A and C be two fixed disks, and B a disk which can be brought at will within a very short distance of either A or C. Let us sup pose all the plates to be equal, and let the capacities of A and C in presence of B be each equal to p, and the coefficient of induc tion between A and B, or C and B, be q. Let us also suppose that the plates A and C are so distant from each other that there is no mutual influence, and that p' is the capacity of one of the disks when it stands alone. A small charge Q is communicated to A, and A is then insulated, and B, uninsulated, is brought up to it; the charge on B will be — (q/p)Q. B is now uninsulated and brought to face C, which is uninsulated ; the charge on C will be C is now insulated and connected with A, which is always insulated. B is then brought to face A and uninsulated, so that the charge on A becomes rO. where A is now disconnected from C, and here the first operation ends. It is obvious that at the end of n such operations the charge on A will be r so that the charge goes on increasing in geometrical progression. If the distance between the disks could be made infinitely small each time, then the multiplier r would be 2, and the charge would be doubled each time. Hence the name of the apparatus.

Nicholson's Doubler.—Erasmus Darwin, B. Wilson, G. C. Bohnenberger and J. C. E. Peclet devised various modifications of Bennet's instrument (see S. P.

Thompson, "The Influence Ma chine from 1788 to 1888," Journ.

Soc. Tel. Eng., 1888, 17, p.

569). Bennet's doubler appears to have given a suggestion to William Nicholson (Phil. Trans., 1788, p. 403) of "an instrument which by turning a winch pro duced the two states of electricity without friction or communica tion with the earth." This "re volving doubler," according to the description of Professor S. P. Thompson (loc. cit.), consists of two fixed plates of brass A and C (fig. 3) , each two inches in diameter and separately supported on insulating arms in the same plane, so that a third revolving plate B may pass very near them without touching. A brass ball D two inches in diameter is fixed on the end of the axis that carries the plate B, and is loaded within at one side, so as to act as a counterpoise to the revolving plate B. The axis P N is made of varnished glass, and so are the axes that join the three plates with the brass axis N 0. The axis N 0 passes through the brass piece M, which stands on an insulating pillar of glass, and supports the plates A and C. At one extremity of this axis is the ball D, and the other is connected with a rod of glass, N P, upon which is fixed the handle L, and also the piece G H, which is separately insulated. The pins E, F rise out of the back of the fixed plates A and C, at unequal distances from the axis. The piece K is parallel to G H, and both of them are furnished at their ends with small pieces of flexible wire that they may touch the pins E, F in certain points of their revolution. From the brass piece M there stands out a pin I, to touch against a small flexible wire or spring which projects sideways from the rotating plate B when it comes opposite A. The wires are so adjusted by bending that B, at the moment when it is opposite A, communicates with the ball D, and A communicates with C through G H; and half a revolution later C, when B comes opposite to it, communicates with the ball D through the contact of K with F. In all other positions A, B, C and D are completely disconnected from each other. Nicholson thus described the operation of his machine : "When the plates A and B are opposite each other, the two fixed plates A and C may be considered as one mass, and the revolving plate B, together with the ball D, will constitute another mass. All the experiments yet made concur to prove that these two masses will not possess the same electric state. . . . The redundant electricities in the masses under consideration will be unequally distributed; the plate A will have about ninety-nine parts, and the plate C one; and, for the same reason, the revolv ing plate B will have ninety-nine parts of the opposite electricity, and the ball D one. The rotation, by destroying the contacts, preserves this unequal distribution, and carries B from A to C at the same time that the tail K connects the ball with the plate C. In this situation, the electricity in B acts upon that in C, and produces the contrary state, by virtue of the communication between C and the ball ; which last must therefore acquire an electricity of the same kind with that of the revolving plate. But the rotation again destroys the contact and restores B to its first situation opposite A. Here, if we attend to the effect of the whole revolution, we shall find that the electric states of the respective masses have been greatly increased; for the ninety-nine parts in A and B remain, and the one part of electricity in C has been increased so as nearly to compensate ninety-nine parts of the opposite electricity in the revolving plate B, while the communi cation produced an opposite mutation in the electricity of the ball. A second rotation will, of course, produce a proportional augmentation of these increased quantities; and a continuance of turning will soon bring the intensities to their maximum, which is limited by an explosion between the plates" (Phil. Trans., 1788, p. Nicholson described also another apparatus, the "spinning condenser," which worked on the same principle. Bennet and Nicholson were followed by T. Cavallo, John Read, Bohnen berger, C. B. Desormes and J. N. P.

Hachette and others in the invention of various forms of rotating doubler.

Belli's Doubler.—A simple and typical form of doubler, devised in 1831 by G.

Belli (fig. 4), consisted of two curved metal plates between which revolved a pair of balls carried on an insulating stem. Fol lowing the nomenclature usual in connec tion with dynamos we may speak of the conductors which carry the initial charges as the field plates, and of the moving conductors on which are induced the charges which are subsequently added to those on the field plates, as the carriers. The wire which connects two armature plates for a moment is the neutralizing conductor. The two curved metal plates constitute the field plates and must have original charges imparted to them of opposite sign. The rotating balls are the carriers, and are connected together for a moment by a wire when in a position to be acted upon inductively by the field plates, thus acquiring charges of opposite sign. The moment after they are separated again. The rotation continuing the ball thus negatively charged is made to give up this charge to that negatively electrified field plate, and the ball positively charged its charge to the positively electrified field plate, by touching little contact springs. In this manner the field plates accumulate charges of opposite sign.

Varley's Machine.—Modern types of influence machine may be said to date from 186o when C. F. Varley patented a type of influence machine which has been the parent of numerous sub sequent forms (Brit. Pat. Spec. No. 206 of 186o). In it the field plates were sheets of tin-foil attached to a glass plate (fig. 5) . In front of them a disk of ebonite or glass, having carriers of metal fixed to its edge, was rotated by a winch. In the course of their rotation two diametrically opposite carriers touched against the ends of a neutralizing conduc tor so as to form for a moment one con ductor, and the moment afterwards these two carriers were insulated, one carrying away a positive charge and the other a negative. Continuing their rotation, the positively charged car rier gave up its positive charge by touching a little knob attached to the positive field plate, and similarly for the negative charge carrier. In this way the charges on the field plates were continually replenished and reinforced. Varley also constructed a multiple form of influence machine having six rotating disks, each having a number of carriers and rotating between field plates. With this apparatus he obtained sparks 6 in. long, the initial source of electrification being a single Daniell cell.

Toepler Machine.—Varley was followed by A. J. I. Toepler, who in 1865 constructed an influence machine consisting of two disks fixed on the same shaft and rotating in the same direction. Each disk carried two strips of tin-foil extending nearly over a semi-circle, and there were two field plates, one behind each disk; one of the plates was positively and the other negatively elec trified. The carriers which were touched under the influence of the positive field plate passed on and gave up a portion of their negative charge to increase that of the negative field plate ; in the same way the carriers which were touched under the influence of the negative field plate sent a part of their charge to augment that of the positive field plate. In this apparatus one of the charg ing rods communicated with one of the field plates, but the other with the neutralizing brush opposite to the other field plate. Hence one of the field plates would always remain charged when a spark was taken at the transmitting terminals.

Holtz Machine.—Between 1864 and 188o, W. T. B. Holtz constructed and described a large number of influence machines which were for a long time considered the most advanced ment of this type of electrostatic machine. In one form the Holtz machine consisted of a glass disk mounted on a zontal axis F (fig. 6) which could be made to rotate at a able speed by a multiplying gear, part of which is seen at X. Close behind this disk was fixed other vertical disk of glass in which were cut two windows B, B. On the side of the fixed disk next the rotating disk were pasted two sectors of paper A, A, with short blunt points attached to them which projected out into the windows on the side away from the rotating disk. On the other side of the rotating disk were placed two metal combs C, C, which consisted of sharp points set in metal rods and were each connected to one of a pair of discharge balls E, D, the distance between which could be varied. To start the machine the balls were brought in contact, one of the paper armatures electrified, say, with positive electricity, and disk set in motion. Thereupon very shortly a hissing sound was heard and the machine became harder to turn as if the disk were moving through a resisting medium. After that the discharge balls might be separated a little and a continuous series of sparks or brush discharges would take place between them. If two Leyden jars L, L were hung upon the conductors which supported the combs, with their outer coatings put in connection with one another by M, a series of strong spark discharges passed between the discharge balls. The action of the machine is as follows: Suppose one paper armature to be charged positively, it acts by induction on the right hand comb, causing negative electricity to issue from the comb points upon the glass revolving disk; at the same time the positive electricity passes through the closed discharge circuit to the left comb and issues from its teeth upon the part of the glass disk at the opposite end of the diameter. This positive elec tricity electrifies the left paper armature by induction, positive electricity issuing from the blunt point upon the side farthest from the rotating disk. The charges thus deposited on the glass disk are carried round so that the upper half is electrified negatively on both sides and the lower half positively on both sides, the sign of the electrification being reversed as the disk passes between the combs and the armature by discharges issuing from them re spectively. It it were not for leakage in various ways, the electrification would go on everywhere increasing, but in practice a stationary state is soon attained. Holtz's machine is very uncertain in its action in a moist climate, and has generally to be enclosed in a chamber in which the air is kept artificially dry.

Voss Machine.—Robert Voss, a Berlin instrument maker, in 188o devised a form of machine in which he claimed that the principles of Toepler and Holtz were combined. In the Holtz machine the collecting system CEDC (fig. 6) served also as the neutralizing conductor. In the Voss an additional neutralizing conductor was placed at an angle with the former. In addition on a rotating glass or ebonite disk were placed carriers of tin-foil or metal buttons against which the neutralizing brushes touched. This plate revolved in front of a field plate carrying two pieces of tin-foil backed up by larger pieces of varnished paper. The studs on the front plate were charged inductively by being con nected for a moment by the neutralizing wire as they passed in front of the paper armatures on the stationary plate, and then gave up their charges partly to renew the field charges and partly to collecting combs connected to discharge balls. In general design and construction, the manner of moving the rotating plate and in the use of the two Leyden jars in connection with the dis charge balls, Voss borrowed his ideas from Holtz.

Wimshurst Machine.—All the above described machines, how ever, were thrown into the shade by the invention of a greatly improved type of influence machine first constructed by James Wimshurst about 1878. Two glass disks are mounted on two shafts in such a manner that, by means of two belts and pulleys worked from a winch shaft, the disks can be rotated rapidly in opposite directions close to each other (fig. 7) . These glass disks carry on them a certain number (not less than 16 or 2o) tin-foil carriers which may or may not have brass buttons upon them.

The glass plates are well varnished, and the carriers are placed on the outer sides of the two glass plates. As therefore the disks revolve, these carriers travel in op posite directions, coming at intervals in opposition to each other. Each upright bearing carrying the shafts of the revolv ing disks also carries a neutralizing con ductor or wire ending in a little brush of gilt thread. The neutralizing conductors for each disk are placed at right angles to each other. In addition there are collecting combs which occupy an intermediate position and have sharp points projecting in wards, and coming near to but not touching the carriers. These combs on opposite sides are connected respectively to the inner coatings of two Leyden jars whose outer coatings are in con nection with one another.

The operation of the machine is as follows : Let us suppose that one of the studs on the back plate is positively electrified and one at the opposite end of a diameter is negatively electrified, and that at that moment two corresponding studs on the front plate passing opposite to these back studs are momentarily con nected together by the neutralizing wire belonging to the front plate. The positive stud on the back plate will act inductively on the front stud and charge it negatively, and similarly for the other stud, and as the rotation continues these charged studs will pass round and give up most of their charge through the combs to the Leyden jars. The moment, however, a pair of studs on the front plate are charged, they act as field plates to studs on the back plate which are passing at the moment, provided these last are connected by the back neutralizing wire. After a few revolutions of the disks half the studs on the front plate at any moment are charged negatively and half positively and the same on the back plate, the neutraliz ing wires forming the boundary between the positively and nega tively charged studs. The dia gram in fig. 8, taken by permis sion from S. P. Thompson's paper (loc. cit.), represents a view of the distribution of these charges on the front and back plates respectively. It will be seen that each stud is in turn both a field plate and a carrier having a charge induced on it, which then passes on in turn and induces further charges on other studs. Wimshurst constructed very powerful machines of this type, some of them with multiple plates, which operate in almost any climate, and rarely fail to charge themselves and deliver a torrent of sparks between the discharge balls whenever the winch is turned. He also devised an alternating current electrical machine in which the discharge balls were alternately positive and negative. Large Wimshurst multiple plate influence machines are often used in stead of induction coils for exciting Rontgen ray tubes in medical work, particularly in countries where other sources are not avail able ; but they cannot compete with sources depending upon elec tromagnetism when great power is required. They give very steady illumination on fluorescent screens.

In 190o it was found by F. Tudsbury that if an influence machine is enclosed in a metallic chamber containing compressed air, or, better, carbon dioxide, the insulating properties of com pressed gases enable a greatly improved effect to be obtained owing to the diminution of the leakage across the plates and from the supports. Hence sparks can be obtained of more than double the length at ordinary atmospheric pressure. In one case a machine with plates 8 in. in diameter which could give sparks 2.5 in. at ordinary pressure gave sparks of 5, 7, and 8 in. as the pressure was raised to 15, 3o and 45 lb. above the normal atmosphere.

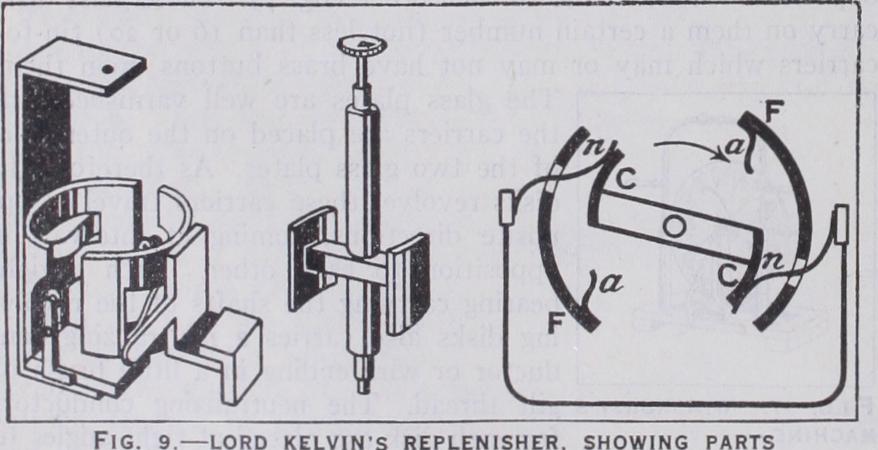

The action of Lord Kelvin's replenisher (fig. 9) used by him in connection with his electrometers for maintaining the charges, closely resembles that of Belli's doubler and will be understood from fig. 9. Lord Kelvin also devised an influence machine, com monly called a "mouse mill," for electrifying the ink in connection with his siphon recorder. It was an electrostatic and electro magnetic machine combined, driven by an electric current and producing in turn electrostatic charges of electricity. In con nection with this subject mention must also be made of the water dropping influence machine of the same inventor.' The action and efficiency of influence machines have been investigated by F. Rossetti, A. Righi and F. W. G. Kohlrausch. The electromotive force is practically constant no matter what the velocity of the disks, but according to some observers the inter nal resistance decreases as the velocity increases. Kohlrausch. using a Holtz machine with a plate 16 in. in diameter, found that the current given by it could in 4o hours only electrolyse acidulated water sufficient to liberate one cubic centimetre of mixed gases. This means that the current was less than one thousandth of an ampere. E. E. N. Mascart, A. Roiti and E. Bouchotte have also examined the efficiency and current-producing pover of influence machines.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-In addition to S. P. Thompson's valuable paper Bibliography.-In addition to S. P. Thompson's valuable paper on influence machines (to which this article is much indebted) and other references given, see J. Clerk Maxwell, Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism (2nd ed., Oxford, 1881), vol. i., p. 294; J. D. Everett, Electricity (expansion of part iii. of Deschanel's Natural Philosophy) (London, 1901) , ch. iv., p. 20 ; A. Winkelmann, Handbuch der Physik (Breslau, 1905), vol. iv., pp. 50-58 (contains a large number of references to original papers) ; J. Gray, Electrical Influence Machines, their Development and Modern Forms (London, 1903) . The design of influence machines is very fully discussed in V. Schaffes, La Machine a Influence (1908). (J. A. F.; A. W. Po.)