Electricity Supply Commercial as Pects

ELECTRICITY SUPPLY: COMMERCIAL AS PECTS. The conditions influencing the supply of electricity in Great Britain have undergone a number of important changes since the legislative foundation of the industry in 1882. The position now, nearly half a century later, considered in the light of subsequent legislation, presents some interesting phases of rhythmic evolution. The events may be grouped in three periods. The first was one of varying activities instrumented by trial and error—technically, commercially, politically. The second was one of fatigue and recuperation followed by splendid performance during the World War. The third is one of re-organization by the Electricity Commissioners. As a consequence, we reach the emer gent conclusions that electricity can be transmitted more easily than coal, it can be sub-divided and applied more effectively than steam, and is more controllable than other forms of motive power. The industry offers scope for enterprise, for investment of capital, for employment of labour, which cannot be estimated without appearance of exaggeration.

First Period.

The first of the three periods referred to covers about 25 years and deals with restrictive legislative con ditions amid technical and financial difficulties which characterized the early struggles for survival of a young industry competing against firmly established gas interests, and later maintaining a defensive attitude against foreign competition developed under far-seeing encouragement. Public opinion in Great Britain in the latter part of the 19th century was adverse to the creation of further monopolies, the general belief being that railway, water and gas companies had received valuable concessions on terms which did not safeguard the interests of the community suf ficiently. At the same time municipal institutions were given wider functions. These legislative measures were not uniformly successful; some proved injurious to the public, others dis couraging to investors. One of these measures was the Tramways act (1870), which twelve years later was followed with the same political outlook by the first Electric Lighting act, imposing onerous conditions of expropriation. Stagnation during many years was the consequence, and recovery was slow. The aggregate capacity of the electrical plants installed in the United Kingdom in 1906 (24 years after the passing of the first Electric Lighting act) was only one million kw. The average load factor of all the British electricity stations was 14.5%. The average capital expenditure was about £8o per kw. of plant. The units sold were 53o millions. The average cost of generation and distribution, excluding depreciation and interest, was 2s. 3d. per unit.With advances in technical practice the advantages of genera tion on a large scale, of distribution over wide areas at high voltages, and of application of electricity in various industries, were demonstrated in other countries, but in Great Britain special Acts of Parliament had to be promoted to authorize effect to be given to these principles. Before this could be done education of public opinion was necessary because strong opposition arose on the part of local authorities, who feared that municipally-owned electrical undertakings would be prejudiced. A joint committee of both houses of Parliament was appointed in 1898, with Lord Cross as Chairman, to consider the bills promoted by enterprising pioneers. This committee recommended that powers should be given for the supply of electrical energy over areas including the districts of several local authorities, and suggested that the then legislative conditions did not apply to such undertakings. While the Electric Power acts passed in 1900 were more consistent with economical development than the provisional orders granted under the acts of 1882 and 1888, the exclusion of the large towns from the acts, coupled with other restrictive provisions, disabled most of the Power act companies from raising the requisite capital, and progress under these special acts was at first very slow and difficult, because the sound policy of supplying cheap electricity in bulk had to be deferred. Successive bills were drafted by the Board of Trade to remove the obstacles, and eventually the Electric Lighting act (19o9) was passed. It conferred wider facilities upon undertakers in minor matters, but the traditional attitude of restraining private enterprise in deference to views in favour of municipal trading permeated the measure, and af forded very little assistance towards building up a comprehensive system of supply. The conspicuous feature in this phase of electrical history is the hundreds of comparatively small generat ing stations, scattered and isolated throughout the country, sup plying in restricted areas, and pursuing the uneconomic policy of independent development.

Second Period.

The second period (1909-19) presented dur ing the first part the effects of disappointment due to unavail ing struggles in the face of flourishing industrial conditions abroad. During this period Dr. S. Z. de Ferranti was presi dent of the Institution of Electrical Engineers for two suc cessive years. In his presidential address, Nov. 1910 (Journal Inst. E.E., vol. 46) he expounded the "all-electric idea" of making an abundant and cheap supply of electricity available by a sup ply of electricity distributed over the country, with a view to coal conservation, production of home-grown food, and the better utilization of labour. This address is a sign-post indicating the main road of electrical progress which the present generation is treading, which in all probability will be followed not only by electrical engineers as pioneers, but by the whole army of British industrialists during the present century. In other addresses he made audible the demand within the industry for a "broader policy" in favour of better organized and more effective solidarity of the technical, commercial and political interests. The remark able improvements which followed the adoption of this policy are best seen by a comparison of the contents of the Journal Inst. E.E. before and after the year 1913 (vol. 52).The transition from a state of depression in the industry was hastened by the outbreak of the World War, followed by un precedented demands for electric power in connection with pro duction of war material. The war changed entirely the general aspects of the industry and initiated radical modifications in the legislative standpoint. The exigencies of the war revealed elec tricity as a vital agent of industrial production; they brought out sharply the defects in the legislative situation, by which co-opera tion in production and distribution was impracticable, and isolated development was fostered. The interconnection of generating stations, desirable with a view to economy in plant, coal and other items of cost, was urged upon electricity undertakers by a Board of Trade circular in May, 1916, and a special department was formed under the Ministry of Munitions to organize the supply of electric power. Despite chaotic conditions the great efforts made by the industry to cope with the urgent and prac tically unlimited call for power were generally successful. The four years of war were equivalent in electrical growth to that of the previous 35 years. The proof afforded of the great national importance of electricity supply led the educated public to think electrically. The following committees were appointed: coal conservation sub-committee of the reconstruction committee (Cd. 888o, 1917) ; electrical trades committee (Board of Trade Cd. 9072, 1918) ; electric power supply committee (Board of Trade Cd. 9062, 1918) ; committee of chairmen of the advisory council of the Ministry of Reconstruction (Cd. 93, 1919). These reports led to the passing of the Electricity Supply act, 1919 (amended by the Act of 1922). As originally drafted the bill met with much opposition, directed chiefly against its compulsory nature and what was regarded in many quarters as a distinct bias towards nationalization in its financial provisions. The contentious clauses were withdrawn, and provision was made for the creation of joint electricity authorities empowered to acquire generating stations and main transmission lines by agreement, but not other wise. The act provided for the appointment of five electricity commissioners. Their general duties are defined as "promoting, regulating and supervising the supply of electricity." Their first specific duty was to determine provisionally "electricity districts," and consider schemes for improving the existing organization for the supply of electricity. Such schemes might provide for the establishment of joint electricity authorities representative of authorized undertakers, within the electricity district, either with or without the addition of representatives of county councils, local authorities, large consumers of electricity, and other interests within the district, and for the exercise by those authorities of the powers of the authorized undertakers. The machinery of the act was of a voluntary nature. The act as passed inspired confidence in the future of the industry; it broke down many prejudices, municipal, political and official; it simplified the procedure for extensions of supply areas, and in the general view constituted the one statesmanlike piece of legislation bestowed on the electrical industry. The appointment of electricity commissioners was in itself a salutary revolution. Their annual reports, the first to March 31, 1921, the seventh to March 31, 1927, are full and interesting records of important events and of beneficial work done.

Third Period.

The third stage covers the period from 1919 to the present time (1928). The year 192o was not favourable to the task of embarking upon extensive schemes of industrial reorganization. The commissioners recognized the fact that "even if the problem could be reduced to engineering considerations alone, the financial stress would constitute a barrier to the speedy development of schemes in different parts of the country." Not only was capital dear and rates of wages high, but prices of plant, materials and fuel were rising. The industry was faced also with the urgent problem of plant replacement. It was the policy of the commissioners not to consent to the establishment of new stations or the installation of additional plant, unless the proposals were technically and financially sound. But the needs were so urgent that often the commissioners found no alternative but to consent to the extension of uneconomical stations, in order that demands upon the undertaking might be met without failure of supply. The knowledge gained by manufacturers during the war had been so well assimilated that even during the time of acute trade depression, which succeeded the period of inflation, and notwithstanding labour troubles—which included prolonged disputes in the coalfields, culminating in the general strike (May I926)—replacement and extension proceeded continuously. An appreciable portion of the work put in hand was expedited ex pressly for the purpose of stimulating the revival of trade and relieving unemployment, and in a number of such cases financial assistance was given by the Government to company undertakings by way of loans guaranteed by H.M. Treasury under the Trade Facilities acts. With similar objects in view advances were made (mainly to local authority undertakers) by the unemployment grants committee. As a further encouragement the Local Au thorities (Financial Provisions) act was passed in 1921 to enable local authorities to suspend sinking fund payments on moneys borrowed for the construction or extension of revenue-producing works, while such works remained unremunerative, subject to a maximum period of 5 years.

In

1920-26 upwards of too (64 non-statutory) new generating stations were sanctioned, including four hydro-electric schemes in Scotland authorized by special acts. The largest of the new stations was of ioo,000 kw. capacity, while 79 others were of smaller capacity than 2 5o kw. each. The figures of the smaller stations are of interest, inasmuch as they represent the inaugura tion of supplies in about 8o new localities, to which no alternative source of supply was available. This increase of generating facili ties has been accompanied by a certain amount of concentration in large stations. The aggregate capacity of generating plant of authorized undertakers in 1927 was practically twice the capacity installed in 1920, but the actual number of stations in operation shows only a small decrease. The process of modernization has been marked by a notable improvement in the efficiency of generating machinery, due to advances in design and manufacture; by an increase in the size of units ; and by change-over from direct current to alternating current.Modern units ranging from 1 o,000kw. to over 3o,000kw. now constitute a considerable proportion of the generating plant in operation, and nearly 90% consists of steam turbo-alternators. The combination of change of type and enlargement of units, coupled with improvements in steam-raising plant and advances in furnace practice, has effected important economies in the utilization of fuel. The lowest fuel consumption recorded at any steam station in 1926 was 1.36 lb. per unit, and the highest thermal efficiency 21.51 %. Both figures relate to the Barton sta tion of the Manchester corporation. The average consumption of fuel, coal, coke and oil, at steam stations was 2-43 lb. per unit, to which figure it has progressively declined from the 3.42 lb. per unit recorded in 1920.

The Growth of Supplies.

A conspicuous feature of post-war development has been the large extension of distribution areas, as many as 329 special orders having been granted during the period under review. The corresponding result in a view of the period as a whole, is seen in a progressive and substantial increase in the consumption of electricity. The sales of electricity by authorized undertakers in 1926 (excluding sales by non-statutory undertakings and the output of traction and private industrial plants) amounted to 5,724 million units. A hindrance to fuller development of the load is experienced in some areas by the prac tice in the past (which in some instances still prevails) of laying mains of a size too small to carry the increased demands now made upon them. The commissioners issued a memorandum on the subject in May, 1927.For the purpose of ascertaining what steps were being taken to encourage and extend the use of electricity for domestic purposes; the relative effectiveness of such steps; and what further steps could be taken to bring about increased consumption, an advisory committee was appointed by the electricity commissioners in April, 1925. The committee's Report was published in Oct. 1926. It refers to the increasing use of electricity for domestic purposes, emphasizing the great potential demand and the value of the load to the supply undertaking, on account of its high "diversity fac tor," and includes an interesting and useful analysis of various multi-part tariffs at present in use. The committee formed the opinion that none of the latter could be recommended as standard for exclusive adoption.

Statistical Summary, 1926.

The industrial position of elec tricity supply in 1926 may now be statistically recorded. There were, in Great Britain, 623 separate undertakers holding statutory powers and owning between them 479 generating stations (264 local authorities and 215 companies) with an installed plant ca pacity aggregating 4,422,00o kw. (practically twice the capacity installed in 1920). The units sold to consumers were 5,724 mil lions, representing about 13o units per head of population. These figures relate to authorized undertakers only, but, including non statutory undertakings, there are altogether 816 electricity supply undertakings with an aggregate capital of 283 million pounds (141 millions in respect of local authorities and 142 millions in respect of companies). The average return on the capital invested in the companies (debenture and shares) fluctuated between 5.58% in 1920 and 6.51% in 1925. For 1926, which was an abnormal year owing to the coal strike, the return fell to 6.21%. These figures reveal substantial expansion ; nevertheless the progress made since the act of 1919, though considerable, was small compared with the potentialities of the industry and with progress in other countries.

The "Weir" Report.

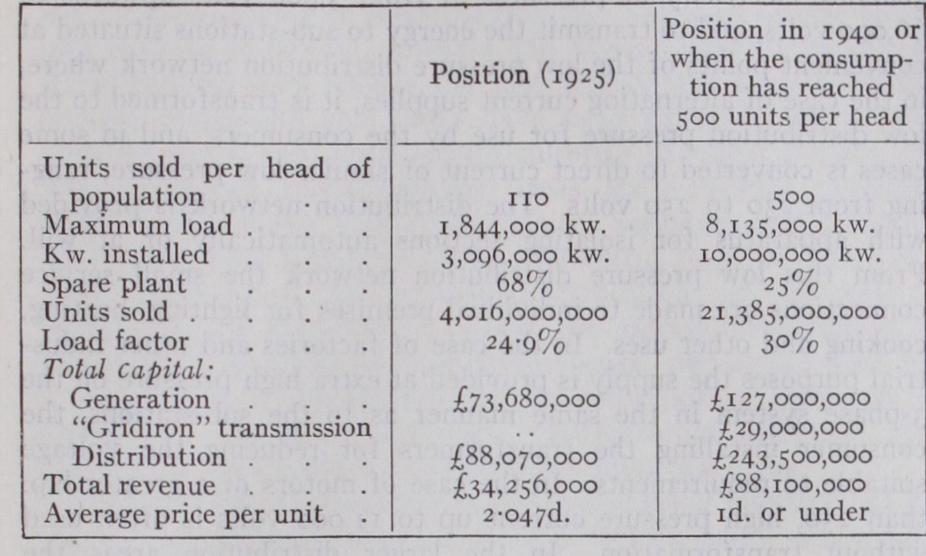

The electricity commissioners in their annual reports made several references to the engineering, financial, administrative and legal obstacles to progress, and in their fourth report (Aug. 1924) they stated that though the powers vested in the commissioners had enabled progress to be made in securing co-ordinated development, it had become apparent that a real organization which would adequately serve the requirements of the country could only be achieved on the voluntary basis of the act of 1919, by a radical change in the attitude of authorized undertakers in general, and that, failing the early disappearance of the obstacles, the whole position would call for review. All parties in the legislature showed alacrity to deal with the problem, and in Jan. 1925 the Government appointed a committee consisting of Lord Weir of Eastwood (Chairman), Lord Forres and Sir E. Hardman Lever, Bart., with Sir John Snell as technical adviser, to consider the general question of the immediate and future electrical development of the country. The committee's report was presented to the minister of transport in May 1925, but was not published until March 1926, when a Government bill, based largely on the findings of the committee, was introduced in the House of Commons. The report recommended the establishment of a comprehensive network of transmission mains (called the "Gridiron") interconnecting all selected stations (43 existing ones and 15 new ones proposed) where generation would be con centrated, entailing the closing down of local generation at 432 existing stations. It further recommended the creation of a new body, termed the Central Electricity Board, with powers to con struct, own and operate the proposed "Grid" system of high ten sion transmission lines; that selected stations should be operated by the owners under the directions of the board ; and that all high tension energy generated by authorized undertakers in the country after a certain date should be generated under control in accordance with a technical scheme for the country, and sold through the board to all authorized undertakers at cost price. It proposed "not a change of ownership, but the partial subordina tion of vested interests in generation to that of a new authority for the benefit of all, and this only under proper safeguards and in a manner which will preserve the value of the incentive of private enterprise." The report contains a picture of what should be aimed at to secure efficient generation of high tension energy in 1940 compared with the year 1925. The salient comparisons are given in the following table: The Act of 1926.—The Government Bill framed to give effect to the recommendations of the "Weir" report was exposed to very keen criticism during its progress through Parliament. It is remarkable that whenever the industry is confronted by a serious crisis, it is not purely technical; not wholly industrial; not alone financial; but essentially political in its character. The opponents of the bill were not opposed to "super-power" developments. They agreed that standardization and systematic grouping, inter connection of existing power systems, generation on a large scale in efficient power stations, and transmission in bulk at high voltage to local distributors, would enable differential outputs to be ad justed, with beneficial results making for increased output, greater efficiency and economy ; but they contended that these results could be better secured by other means and without the novel administrative system of control and economic methods proposed; and the owners of company electricity supply undertakings were nervous lest the proposed legislation should again inflict grievous financial and confiscatory burdens upon them. With considerable amendments of details the measure was finally passed and received the royal assent on Dec. 15, 1926 (16 and 17 Geo. 5. Ch. 51) . By its enactment a radical change in legislative conditions affect ing the organization of the electricity supply industry was brought about. A memorandum summarizing its provisions mainly from the standpoint of the powers, duties and obligations of authorized undertakers was issued by the electricity commissioners in Feb. 1927.

In order to secure the concentration of generation in a selected and limited number of stations, all interconnected and operated under one control, the act discards the principle of co-operative action on a voluntary basis (which was the principle embodied in the act of 1919) and substitutes a compulsory basis through the medium of a new body—the Central Electricity Board. This board, whose functions may be briefly described as the reorgani zation and control of generation, is established as an authorized undertaker for the whole of Great Britain, within the meaning of the Electricity (Supply) acts 1882-1922. The ultimate object in view is that all authorized undertakers shall obtain their sup plies of electricity in bulk from the board, either directly or in directly. For this purpose certain generating stations will be "selected" and interconnected, and operated by the owners on behalf and under the control of the board, who will purchase all the output of such stations at a price (being the cost of produc tion) to be ascertained in accordance with prescribed rules. Dis tribution and commercial development is left in the hands of the undertakers as heretofore, who will purchase from the board the supplies they require (within specified limits) at a price, unless otherwise agreed, equal to the cost of production as ascertained and adjusted, plus a proper proportion of the board's expenses or according to the tariff fixed under the act, whichever is the lower. In the case of non-selected stations, the owners (being authorized undertakers) may demand a supply of electricity from the board, in which case they may be required to close down their local generating stations and take the whole of their supplies from the board. There are other circumstances in which the owners of a non-selected station may be required (by an order of the elec tricity commissioners) to close down local generation, namely when the Board notify that they are in a position to supply the full requirements of the undertaking at a cost below the then prevailing cost of generation at the station in question. The act does not contemplate the construction or operation, or the trans fer of any generating stations to the board itself, except as a last resource, when they are unable to enter into an arrangement with any authorized undertakers or other company or person to operate such stations, or extend, alter or construct such stations as the case may be. The act contains various clauses for the pro tection of undertakers, but the commercial and, it is feared, the legal interpretations, are very involved. The board has power to borrow money with the consent of the commissioners and subject to regulations made by the minister of transport with the approval of the Treasury up td a maximum of £33,500,000, which money may be raised by the issue of central electricity stock, but power may be conferred on the board by special order to borrow in excess of that amount. The act makes provision for the prepara tion, adoption and carrying out of schemes of technical develop ment ultimately covering the whole country. The Central Elec tricity Board consists of a chairman and seven other members appointed by the minister of transport "after consultation with representatives of local government, electricity, commerce, in dustry, transport, agriculture and labour." (Sir Andrew R. Dun can [chairman], Sir James Devonshire, K.B.E., Frank Hodges, Sir James Lithgow, Bart., W. Walker, Sir Duncan Watson, W. K. Whigham and Lt.-Col. the Hon. Vernon Willey, C.M.G.) The chief engineer and manager is Mr. Archibald Page (formerly an electricity commissioner). The secretary is Sir John R. Brooke, C.B.

Four schemes under the act have already been drawn up by the electricity commissioners and published by the Central Elec tricity Board. The first was transmitted by the commissioners to the central board and published by the board on May i 1, 1927. It dealt with central Scotland, covering an area of about 4,980 sq.m. with a population of 34 millions, including roughly the whole of the industrial, shipbuilding and coalfield areas of Scotland. At the present time there are 42 authorized undertakers in the area, owning between them 36 generating stations. Under the scheme ten existing stations will be selected and operated for the board. The scheme contemplates the erection of two new stations of not less than ioo,000 kw. each by the year 1938. The transmission system is designed in a series of ring mains, so that there will be alternative routes to points of supply. The primary line voltage adopted is 13 2,00o volts. The scheme involves a large measure of standardization of frequency—no fewer than eleven under takings and five generating stations will have to be altered from 25 to 5o cycles. The scheme, with certain modifications, was adopted by the central board on July 1, 1927. The second scheme was transmitted on Sept. 29, 1927. It deals with south-east England, covers an area of 8,828 sq.m. including the London and home counties electricity district, and extends from Peterborough in the north to Brighton in the south, with a popu lation of over 11 millions. The third scheme is for Central Eng land and the fourth is known as the north-west England and north Wales scheme. Other schemes dealing with south-west England and south Wales are being prepared.

In the opinion of the commissioners the improvements in the organization for the supply of electricity which have taken place during the post-war period, will serve to facilitate the transition to the new regime laid down by the act of 1926. This important industry of nearly 5o years' standing is now for the first time placed under authorities able to deal authoritatively with tech nical, commercial and financial problems of the industry on their merits, in the national interests, in a large measure freed from local administrative restrictions. It is emerging from a state of bare existence to the full enjoyment of its life, with energies directed to rendering valuable services to the community. It has an ill-advised inheritance of legislation, but a naturally strong constitution which enables it to regard difficulties and adversity as normal antecedents to technical success and commercial pros perity. As a matter of historical interest 12 years hence, it may be said that though the objections to many of the provisions of the 1926 act are valid, it is generally agreed that loyal and co-opera tive effort on the part of undertakers to make the operation of the act successful, is now more important to the realization of the all-electric idea than adverse criticism of the legislative ma chinery. The complementary condition of this consummation is all-round confidence that justice will be done in the difficult ad justments of rights, duties and interests between investors and workers on the one hand, and consumers on the other, having regard to past sacrifices and future services of the former and the paramount demand by the latter for cheap electricity as an essen tial to maintenance of national welfare.

The London Position.

After many years of controversy the problem of electricity supply in London is in process of solution. The limitations of the early electric lighting acts were sufficiently difficult in relation to provincial undertakings, but they were ac centuated when applied to the metropolis. "London" is an agglom eration of towns and local authorities, and in the sense of the Electric Lighting acts the boundaries of a borough constituted the limits of an electric lighting area. Moreover, the generating sta tion had to be erected within the municipal area of supply. The history of attempted reform of the London position dates back to 1905, and is summarized in Garcke's Manual, 1915-16, vol. xix., pp. 16-19, and 1926-27, vol. xxx., pp. 596-8 and 611-5. See also 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th Annual Reports of the Electricity Commis sioners. Nothing tangible was achieved until the London Electric Supply acts 1908 and 1910 were passed. Under these acts the powers to purchase the undertakings of the companies in the administrative county of London, which would otherwise have been exercisable for the most part in the year 1923 by the metro politan borough councils, were modified, inter alia by extension of tenure to 1931, and transferred to the London County Council. Under the Electricity (Supply) act, 1919, the London and home counties joint electricity authority was established as from July 29, 1925. The district of the joint authority includes the whole of the counties of London and Middlesex, and parts of the counties of Herts., Essex, Kent, Surrey, Bucks. Berks. The local government areas comprised in the district include the City of London, the City of Westminster, 27 metropolitan boroughs, 3 county boroughs, 16 municipal boroughs and a large number of urban and rural districts. The population at census of 1921 was 8,178,766; the assessable value on April 6, The total number of authorized distributors is 89, namely, 44 local authorities and 45 companies. The position of the company under takings was wholly altered by the London Electricity (No. 1) and (No. 2) acts, 1925, and the London and Home Counties Elec tricity district order, 1925. Under these the London companies secured an extension of the tenure of their undertakings until 1971, when such undertakings will be transferred to the London and home counties joint electricity authority. Prices to be charged for electricity and dividends to be paid to shareholders will be regulated by a sliding scale, and sinking funds will be set up by the operation of which the existing assets of the companies will be transferred to the joint electricity authority in 1971 free of cost, and new assets will be transferred at cost price less depre ciation. Under the powers conferred by the London Electricity (No. 1) act, the promoters, namely, the City of London, county of London, south London, and south metropolitan companies, have prepared a scheme subject to approval by the electricity commis sioners, under which the operation of the generating stations of the four companies would be directed by a joint committee. These generating stations have been joined by interconnecting cables. The remaining ten companies which promoted the No. 2 act have formed a new company now called the London Power Company, Limited, the board of which consists of a representative of each cf the ten companies. This company has taken over the generat ing stations and main transmission lines of the ten companies, and these, retaining their full and complete rights as authorized dis tributors, now purchase in bulk from the London power company the whole of the electricity which they require for supply in the county of London.

Transmission and Distribution.

The present practice is to generate electricity at pressures of from 5,500 volts upwards to 66,000 volts, and to transmit the energy to sub-stations situated at convenient points of the low pressure distribution network where, in the case of alternating current supplies, it is transformed to the low distribution pressure for use by the consumers, and in some cases is converted to direct current of similar low pressure, rang ing from 230 to 250 volts. The distribution network is provided with apparatus for isolating sections automatically or at will. From this low pressure distribution network the small service connections are made to individual premises for lighting, heating, cooking and other uses. In the case of factories and other indus trial purposes the supply is provided at extra high pressure on the 3-phase system in the same manner as to the sub-stations, the consumer installing the transformers for reducing the voltage suitable to requirements. In the case of motors of a greater h.p. than 25o, high pressure current up to i 1,000 volts is often used without transformation. In the larger distribution areas • the 3-phase system alternating 50-periods per second is now becoming standard. In thickly populated districts the standard practice is to employ cables with conductors insulated by paper impreg nated with oil, surrounded by a lead sheath which, in many cases, is further externally protected by steel wire or tape binding, this system being employed for both high and low pressure cables. These cables are either laid direct in the ground or drawn into earthenware conduits at a depth of 2' 6" to 3' o" below the surface. The alternative method of distributing electricity is to carry the conductors overhead.The cost of providing cables underground is approximately three times that of overhead conductors of similar current-carry ing capacity. In congested areas the density of the demand may justify the increased cost of underground cables, but the problem of distributing electricity in rural districts is now receiving atten tion ; and to enable these services to be given at prices which the consumers can pay, the cost of distribution must be kept down, because the distribution network in rural areas is large in relation to number of consumers. Overhead lines outside the more con gested centres of population are being increasingly adopted, but not sufficiently, if the rural load is to develop to the large extent which the potential demand indicates. The subject is closely bound up with questions of way-leaves and pole rentals, and the standard of construction demanded under the commissioners' 1923 code of regulations. A revised code of Overhead Line Regu lations was issued by the Commissioners in April 1928 (El. C. 53). The high cost of construction imposes a handicap on development, particularly with low voltage lines. A memorandum on electrical development in rural areas was issued by the electricity commis sioners in Aug. 1927, inviting the active support of local authori ties, landowners and others able to afford facilities in connection with overhead lines and way-leaves. Further steps were taken in Nov. 1927 by a conference of various bodies interested in different aspects of rural electrification, to review the whole position. A report was issued by the Electricity Commissioners in July 1928. The Overhead Lines Association was formed in Oct. 1927 at the suggestion of Mr. R. Borlase Matthews, M.I.E.E., to co-ordinate experience and special knowledge of the subject.

Rural electrification points to ruralization of industries, with electricity distributed economically to factories on relatively cheap land. Decentralization of large composite works and segregation cf factories for production of standard parts are easily conceiv able developments. The social effects are not at present calculable, as many factors are still indeterminate, but the beneficial influ ence of these impending changes upon the relations between labour and capital, and upon the problems of unemployment, cannot be overlooked. The important point to note is that there is no na tional monopoly in electricity ; it is an all-world development, with economic potentialities difficult to measure, with social and ethical probabilities interesting to contemplate. A few words on the sub ject of electricity in agriculture are apposite. Electro-farming is an important recent development. As farms employ more power, in the aggregate, than all other industries put together, the cap ture of the farming load is most interesting from the point of view of the electrical engineer, and the fact that probably over a mil lion of the world's farmers are using electricity (including 75o in this country) points to further advances. This new service has its own journals in Britain, America and Sweden, and a recently col lected bibliography reveals the fact that over 60o authoritative articles, pamphlets and books have been written upon it, over 20% of which deal with electro-culture. In Great Britain, the most `advanced electro-farming areas are Fifeshire, Ayrshire, south Wales, north 'Wales, Shropshire, Somerset and Cheshire, while near East Grinstead is an all-electric farm of 65o acres, where some 67 of the 200 known applications of electricity to agriculture are installed. In cities the annual consumption of electricity is based on units (kilowatt-hours) per square mile, but in rural areas it should be based on units (kw.hr.) per mile of distributor. On this basis, rural electrification compares very favourably with statistics available for suburban areas.

Manufacture.

The electrical manufacturing industry has ex perienced exceptional difficulties and undergone many vicissitudes. In its early days the various departments which are now devel oped as separate industries were closely allied. Thus the manufac turer was linked by various bonds, especially that of finance, with the inventor and entrepreneur, the parliamentary promoter of pub lic utility undertakings, and the constructor of works, for he could not obtain employment for his factory unless he was inter ested in the initiation of enterprises. But during the World War the manufacturers gained experience in mass-production, and diverse industrial functions were segregated and became special ized. Subsequently in the post-war period of transient inflation, kindred businesses were again united by allied finance rather than in coalescence, and large combines of separate but interconnected companies were created for the furtherance of common interests and execution of large composite contracts. During the pre-war period when the industry was involuntarily inert, owing to im peded growth, manufacturers in America and in Germany, who had the encouragement of growing demand for apparatus, de voted their resources to the development of efficient selling organi zations at home and abroad ; with the result that they were able to take advantage of the system of free imports to secure orders in Great Britain for plant and machinery. The British electrical industry has been reproached for being in a backward condition, but the wonder is that it has got so far forward. Under changed surroundings of ter the war the electrical manufacturing branch recovered rapidly as compared with other branches of the en gineering industry. Since the 1907 census of production the elec trical output has increased from 13 million pounds to an estimated output of 8o millions in 1927, an increase of 500%, which is con siderable in relation to the figures for general engineering products for the same period. The conspicuous progress of the industry is not by any means merely a quantitative increase. As Mr. Dunlop, the director of the British Electrical and Allied Manufacturers Association has shown, side by side with the growth in volume has proceeded a progressive improvement in quality and efficiency, the result of intensive research work for which the manufacturer had no funds under pre-war conditions. In the case of generating machinery, for example, fuel consumption has been reduced within the last five years by nearly 30%. Recent figures of exports indi cate an advance relatively to other nations. In 1913 Germany dominated the electrical export trade of the world. In 1927, how ever, Britain has moved into the first place among electrical ex porting countries. "The displacement of trading strength," says Sir Hugo Hirst, "justifies the assumption that the technical and manufacturing efficiency of British firms now stands at a higher point than at any previous time. In quality as apart from mass production their superiority can scarcely be challenged." It can be assumed, he says, that of the total production of electrical apparatus at least four-fifths represent direct and indirect wages paid. This means that the industry gives employment to probably 600,000 workers, or 320,00o in addition to the 280,000 it employs directly. The electrical manufacturer therefore is fighting for more than his own industry, and there are few industries in this position, at least of the same importance. The fact that an im proved margin of profit has been earned need not be regarded as an effect of co-operation to keep prices above an economic level. As a matter of fact, the moderate improvement in net profits of electrical manufacture during the post-war period has been ac companied by substantial reductions in selling prices of electrical goods in relation to altered money values, cost of living, wages and other economic factors which enter into determination of price levels. An international comparison of prices in relation to costs of production is, however, rendered excessively difficult by variable classifications of manufactured goods, and by lack of information as to debit and credit items making up the effective costs for pur poses of foreign competition. The history of the British electrical industry demonstrates in an accentuated form the truism that unrestricted competition leads to inability of an industry to do justice to essential interests of producer, consumer and commu nity. Unduly low prices mean reduction and perhaps even elimi nation of profit, and this deters capital required for improvements, extensions and research, and produces disturbing conditions owing to fear of wage reductions ; while consumers and users suffer in quality of commodities supplied and services rendered.The following are financial figures relating to manufacturing undertakings in the three typical periods of the electrical industry : Number of Year companies Capital 1910 265 1920 280 £63,908,000 1926 . . . . . . . 365 £89,291,000 The average rates of net profits earned by such of the com panies and firms whose accounts are published are for the year 191o, 5.22%; for 192o, 9.98%; for 1926, 7.73%.

The aggregate subscribed capital and loans authorized in 1926 of 1633 British electrical undertakings of all kinds amount to over £8i8 millions.

These undertakings are classified as follows:— Telegraph Companies 50,165,000 Telephone, Companies . 9,251,000 Telephone, Government and Municipal Expenditure Electricity Supply, Companies 142,470,000 Electricity Supply Municipalities, Loans authorized 140,,568.000 Electric Traction, Companies 181,866,000 Electric Traction Municipalities, Loans authorized 89,686,000 Manufacturing . 89,291,000 Miscellaneous . . . . . . . 42,720,000 £818,752,000 Research Work.—Following the rapid expansion of the indus try during the war, it became evident that co-operative research was necessary for continued technical and commercial progress. An electrical research committee was formed in 1917, and a few years later this committee was reconstituted as the British Elec trical and Allied Industries Research Association (E.R.A.) under the scheme of the department of scientific and industrial research which was established in 1918, the Government placing at the disposal of the department one million sterling to enable it to encourage the industries of the country to undertake scientific research. It is estimated that the membership of the E.R.A. represents about 85% of the capital employed in manufacture in the industry. The work of the E.R.A. now covers a large part of the field of research in the industry. The results are embodied in technical reports issued to members of the association, and about one-third of the reports have been published for the general benefit of the industry, mostly through the Journal of the Institu tion of Electrical Engineers. There are many problems which show great promise but which have to be postponed for lack of adequate funds, notwithstanding that the solutions are urgently needed. It must be added that large sums are being spent on research by individual firms; and that brilliant achievements are recorded in the field of theoretical physics, which, however, lead to further technical investigations for their practical application. In 1925 the electricity commissioners addressed representative sections of the industry with the view of enlisting active support for the work of the association.

Standardization.

Recognition of the principle of standard ization arises early in the organization of every industry, but until a considerable degree of prosperity and solidarity is attained, by which individual interests and jealousies are merged in collective interests, its growth is slow. The first edition of the I.E.E. Wiring Rules was issued as early as in 1882, but it required many years before rival manufacturers could agree on standardizing even such small things as switches, plugs and lamps. In 19o1 the British Engineering Standards Association (then called the Engineering Standards Committee) appointed a sub-committee for standard ization of electrical plant. In 1906 Colonel R. E. Crompton founded the International Electrotechnical Commission, and the British National Committee was appointed to co-operate in this work. One of the many objects was to discourage the use of varying specifications by individual engineers when one specifica tion would serve the purpose. The B.E.S.A. has now 7o committees preparing electrical specifications. The I.E.C. by its various com mittees is itself directly engaged in important co-operative stand ardization, and committees considering questions of electrical standards (mostly for reference to the B.E.S.A.) exist within various sectional electrical associations, while practically every industrial and scientific body in the electrical industry lends its active support to the work. In 1919 a Government inter-depart mental committee was set up to co-ordinate the electrical require ments of the Government departments, and this committee works in close co-operation with the B.E.S.A. In 1925 the membership of the B.E.S.A. was made available to all connected with the industry on payment of an annual fee. The B.E.S.A. has endeavoured to set up standards of quality in materials and apparatus. Those standards are not confined to technical require ments, but are of value also on the commercial side, as is seen in the I.E.E. Model Conditions of Contract. Conditions of employ ment have also been standardized to a certain extent in the electrical industry. Probably one of the most valuable pieces of work brought to completion is the British Standard Glossary of Terms used in Electrical Engineering. The increase in production and the rapid spread of distribution of electric power on a large scale have created many new problems of standardization, for the consideration of which reference may be made to articles by Mr. P. Good in the I.E.E. Journal, vol. 64, April 1926, vol. 65, Jan. 1927, vol. 66, Jan. 1928.

Growth of Associated Effort.

Compared with the almost entire absence of solidarity in the industry previous to the adoption in and 1913 of "the broader policy" by the I.E.E. and various other bodies representative of electrical interests, there is now a marked improvement in the general organization for the promo tion and protection of collective interests, and for collaboration on matters calling for joint examination and action. There are no fewer than 5o different associations, institutions and societies representing or concerned with diverse electrical affairs. There is not space to mention all ; a full list appears in the Manual of Electrical Undertakings.From the standpoint of production and distribution, the pre-war progress of electricity in old countries was not commensurate with the advance and potentialities of the science. A study of the causes shows that the main deterrent factors are to be found in the complexity of the industrial organism and the social conditions of the particular country and period. The industries in general were firmly established on a steam-using basis ; plant efficiency was high, and fuel cheap. Central power stations were therefore de pendent for the most part on the advent of new industries or on a combination of circumstances in old factories which justified the conversion of steam to electrically-driven equipment, and the concomitant sacrifice of capital in the discarded installation. The element necessary for the economical generation of electricity, namely, a large and diversified demand for power, was absent or available only in a small degree. The standard of wages, too, precluded a considerable section of the people from adopting electricity for domestic purposes in preference to gas, the mains for which were laid in all the streets, whereas electrical distribution mains were, by reason of their almost prohibitive cost in relation to inadequacy of demand for current, confined to the principal thoroughfares and the better-class residential districts. But a new orientation has arisen : the adaptation during the war period of sc many factories to electrical operation, the greatly increased cost of fuel which has deflected the scale against private steam plants, and the higher standard of living and domestic needs, constitute conditions which will enable the science of electricity to exercise a determining influence upon the future industrial and social development of European countries.

In new countries the door to electrical development was open from the outset ; the field for enterprise was ready for exploration. Industries were few and of small extent. Gas, where supplied, was dear. Oil and candles were the mainstay for illuminating purposes. Legislation, if any, was benevolent. In a comparatively short space of time, communities, even those remote from the arteries of communication, contrived to harness the local streams and to enjoy the benefits of electricity supply. In the case of America, the virile genius of the people quickly surmounted initial diffi culties standing in the way of obvious benefits to be secured ; by the end of the nineteenth century a few large central stations had displaced many small stations, and electric current for all purposes was available over wide areas. The primary need was capital for new steam and hydro-electric undertakings and extensions of existing stations. The funds at command nationally were relatively meagre. European money, mainly British, was available, but in amount too small to meet the needs. Nevertheless, the progress in the United States was considerable. Electricity supply had opened up a vista of cheaper manufacture of commodities imported from overseas. The industrial instinct of the nation was awakened. Heavy, if not prohibitive, import duties were imposed. And thus, step by step, the United States emerged from an agricultural country into an industrial state with vast potentialities for home and export trade. By fertile combination of natural resources, growing population, intellect unhampered by national tradition, and with freedom from anxiety for conservation of capital invest ments in obsolete plants—all these causes, conjoined with the rapid accretion of wealth, have enabled the United States to occupy a place far ahead of any other nation in the domain of electricity supply, inasmuch as its installed generating plant capacity of 2 2 million kw. equals that of all the European countries combined. Canada, inspired by the example of its prosperous neighbour, made strenuous efforts towards development through the agency of its beneficent water powers ; and not unsuccessfully, for with a popu lation of only 9 million it has already installed more than 21 million kw. of generating plant, whose output is largely utilized by the pulp and paper, mining and other industries which have con tributed so much to the country's welfare. Other constituent parts of the British Empire—Australia and New Zealand, South Africa, India, the Crown Colonies and Mandated Territories — are markedly active in the development of their civic and industrial life by means of electricity supply derived from water powers, coal, oil, and plantation refuse respectively to local conditions. The great republics of South America, stimulated by the influx of foreign capital, have schemes for electricity supply throughout their territories, and bid fair to become large producers of current and users of electrical plant. Japan continues steadily to western ize its industries, and has an installed generating plant capacity exceeding 21 million kw., and an estimated annual expenditure on electrical goods equivalent to £21 millions.

France, despite its war wounds, is forging ahead with ambitious electrical schemes, including networks of transmission lines and super-power steam stations in the industrial districts in the north, and hydro-electrical developments in the south. It possesses an installed plant capacity of over 41 million kw. Belgium, with revived industrial activity, uses about 14 million kw. of gener ating plant. Germany before the war, under the guidance and influence of its Government and the sustained assistance of its financial institutions, held a prominent, if not pre-eminent, posi tion in the hierarchy of producers of electrical plant, and is again striving to recover supremacy. It has an installed plant capacity of about 6 million kw. 8o% of the output of its public generating stations is utilized for industrial purposes, or the same percentage as in the case of France ; while the corresponding figure for Britain and the United States is only 65%. Scandinavia has over 2i million kw. of generating plant installed, and Switzerland 6,900 hydro-electric undertakings operating million kw. of plant. The engineers of these countries enjoy a high reputation, and water turbines and generators of Swiss and Swedish manufacture are found in many of the principal hydroelectric installations in North America. The industrial position attained by both these countries demonstrates the enormous value of electricity in overcoming the handicaps of mountainous terrain and absence of coal deposits. Switzerland has the distinction of producing 75o kw. hours of electricity per inhabitant per annum, or more than that of any other nation. Italy has nearly 2,400,00o kw. of steam and hydro electric plant in service, of which about 9o% is used for industrial purposes; while a government commission is engaged (1928) in elaborate investigations of the country's resources and markets for electricity supply. Russia has rehabilitated its generating stations and erected many new ones, but awaits capital resources for indus trial expansion. Spain has large existing and projected installations in the Pyrenean zone. The Netherlands, Czecho-Slovakia, and other countries of Europe also furnish evidence of substantial electrical progress.

The conference on the world's power resources held at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley, London (June–July, 1924), under the aegis of the British Electrical and Allied Manu facturers' Association, and the patronage of the British Govern ment, was epochal in the annals of electricity supply and of international relations. The conference was attended by repre sentatives—technical, commercial, financial and legal—of foreign governments and of many electricity supply undertakings thtough out the world. Papers were read by experts of no less than 22 different nationalities, who contributed to the dissemination of information calculated to further the progress of electricity supply in all its ramifications throughout the civilized world. The Transactions of the Conference (5 volumes, Lund, Humphries and Company, Ltd., London) rank among the most valuable con tributions of modern times to applied science.

The following figures, extracted from publications by the B.E.A.M.A., indicate approximately the magnitude of the elec trical industry in the principal countries of the world : Total Production of Electrical Goods . . . £600 million Internal Consumption of Electrical Goods . . £528 million Exports (less Imports) of Electrical Goods . £ 72 million Capacity of Generating Plant installed . . 53 million kw.

Output of Electricity 141,00o millions of units (kw. hours) .

(E. GAR.) Electric central station service in the United States is available in every city of 5,000 population or more; in 97% of all com munities between i,000 and 5,000; in 5o% of all communities between 25o and 1,000; and in 25% of all hamlets of less than 2 5o inhabitants.

The electric utility industry, by which is meant the production, transmission and distribution of electric current by companies formed for that purpose and serving the general public without discrimination, had its birth in 1882 when Thomas A. Edison established the first central station in the world in New York City. This little Pearl Street station started with a few score customers in an area of 12 city blocks, and had a total generating capacity of 1,200 horse power. Current was used only for lighting, in electric arcs and the recently invented carbon-filament incandes cent lamps.

In 1927, less than half a century later, the electric utility in dustry in the United States had a total of 21,694,00o customers, reaching about 8o,000,000 of the population, and an installed generating capacity of nearly 40,000,00o horse power.

There are in the United States 4,40o electric utility enterprises, including both those privately and municipally owned. These represent an investment of more than 92 billions of dollars, and require about one billion of new capital a year for maintenance, expansion and development.

Following the demonstrated success of the Pearl Street station, electric utility plants were built in city after city and town after town in rapid succession. Water-power at this early period began to be used to drive dynamos to generate electricity, though the difficulties of transmitting current over long distances made only favourably located water-power sites available for this purpose. The first hydro-electric central station was established at Apple ton, Wis., in 1882, closely followed by the harnessing of Niagara Falls for the production of current for sale to the public. As late as 1891 the art of transmission was so little known that it was considered impossible to transmit power from Niagara Falls to Buffalo, 16 m. away. Niagara Falls now produces more than one million continuous horse power, part of which is transmitted zoo miles.

Growth and Control of the Industry.

The history of the electric utility industry through the remaining years of the century is a story of tumultuous but steady growth. Central station plants were built in increasing numbers, and since there was at this time no governmental control, fierce competition existed. Rival com panies for the same city or district fought each other, and rates were cut until one company absorbed the other or they mutually ruined themselves, while the public demand for electric service steadily grew. Out of this early chaos came, State by State, the recognition that electric service was essential to the public well being ; that electric utilities were "affected with a public interest"; and that, for the benefit of the public, as well as of the companies, competition must give way to a State-regulated monopoly. Vari ous kinds of regulation were tried, and from these has evolved the typical public service commission now in operation in every State but Delaware. Members of public service commissions are usually appointed by the governor of the State for a period of years, and serve as representatives of the public in the supervision and regulation of all public utilities, not electric companies alone. Water supply, gas, electricity, street railway, bus, express, tele phone and telegraph companies are generally listed among public utilities.The economic theory underlying regulation of public utilities is one of reciprocal benefit ; in return for an exclusive privilege to serve a given territory and make use of public property, such as streets, the State assumes the right to supervise and regulate utility rates and standards of service for the benefit of the public.

Public service commissions have as their main function the assurance to the public of safe and adequate service at fair and reasonable rates. To this end they are given broad powers over accounting, financing, rates and service. Since it is equally in the public interest that a utility be able to maintain, improve and enlarge its service as the demand increases, it is also a function of public service commissions to see that properly managed com panies are permitted to charge rates which will provide a reason able return upon capital invested in furnishing the service.

It is under this general form of State regulation of private enter prise that the electric utility industry of the United States has made its extraordinary record of growth during the present cen tury, to a point where the country uses nearly as much electricity as all the rest of the world.

The total cost of Federal and State regulation of public utilities and railroads in the United States is estimated to be about $12, 000,000 a year, whereas the electric utility industry alone pays taxes aggregating more than 1 so million dollars.

During the early years of the electric service industry numerous municipally owned and operated central stations were built. In many cases these were established in smaller communities, into which private capital was fearing to venture. The number of municipal enterprises increased from 815 in 1902 to a peak of 2,581 in 1922. Of this number, 1,82o operated generating plants, and the remainder purchased current for distribution. Privately owned enterprises in this same period increased from 2,805 to 3,615. Between 1922 and 1927 the number of municipal establish ments decreased by more than one-fifth, and between 1917 and 1927 it is estimated that approximately 90o municipal electric enterprises throughout the United States were abandoned or put under private operation. Municipal electric companies in 1927 supplied less than 5% of the customers of the industry. The nationwide trend toward the consolidation of electric generat ing plants into interconnected, or so-called "superpower," sys tems has been an outstanding factor in the elimination of the small isolated unit. This development has applied peculiarly to municipal plants, which in the United States has tended to serve a restricted area only.

The relative economic merits of municipal and private opera tion of electric service systems is discussed in the 1927 report of the committee on public ownership and operation of the National Association of Railroad and Utilities Commissioners. Quoting a detailed study of electric utilities under private and public operation made by the chamber of commerce of the United States, the report says, "In every count the advantage is with the private concern. Excluding taxes, operating expenses in the public plants exceeded those of the private plants by 20%. In the manufacture of current the cost to the public plant was found to be 33% more per kilowatt-hour than to the privately owned plants. The distribution of current cost 20% more. Labour costs were 53% more, and costs of fuel 13% more. The labour effi ciency of the public plant was 26% below that of the private concern, while the loss of current through leakage showed an advantage in favour of the private business of 31%. As a general thing, utilities owned and operated by the public furnish inferior service to that furnished by privately owned and operated util ities. United States conditions thus present a direct contrast to British statistics.

An outstanding feature in the growth of the electric service industry in the United States has been the development, largely since 1914, of interconnected, or "superpower," systems, whereby transmission lines covering vast areas, sometimes several States, form great power pools, fed by a number of generating stations, both steam and water-power. These may belong to different utility companies, and may be widely separated. Increased relia bility of service and economies of operation result from inter connection, while the widespread network of transmission lines makes service available to many communities otherwise without it, or ill-served by small and isolated plants. Electric utilities in the United States have built more than 135,0o0 miles of trans mission lines.

Through the consolidation of smaller enterprises by intercon nection, and the abandonment of uneconomic isolated plants in many parts of the country, the number of individual electric systems decreased 33% between 1922 and 1928, whereas the num ber of communities served by them increased by 5,000 or about 37%. The ultimate destiny of the United States is to be cov ered with a network of interconnected transmission systems fed by strategically located generating plants and reaching every community.

Output.

In 1927 125 electric utility systems produced 1 oo million kilowatt-hours or more of current each, and, of these, 18 produced a billion kilowatt-hours or more each. One single system, at Niagara Falls, generated nearly 41 billion kilowatt hours during the year, the largest individual production in the world. These 125 systems supplied more than four-fifths of the nation's electric power generated by utilities, and with additional current purchased by them for distribution, supplied 97%.Increasing size of generating units, i.e., steam turbines and high pressure boilers, has continued, and whereas in 1910 a io,000 kilowatt unit was considered large, 150,000 kilowatt units are now in service, and one of 200,000 kilowatts was recently con structed. With the construction of larger and more efficient plants, the coal required to generate one kilowatt-hour had de creased from more than 3 lb. in 1919 to less than 2 lb. as a national average in 1928.

The present installed capacity of all the central stations of the United States is approximately 36,000,00o horse power, of which 24,000,000 horse power are in fuel-burning plants, and 11,720,000 horse power in water-power plants.

The conservation of coal resulting from increased thermal effi ciency in electric utility plants, as compared with 1919, was in 1927 about 5% of all the coal used in the country. And if the electrical energy used to drive industrial motors in 1927 had been generated by small factory plants instead of being purchased from the water-power and high-efficiency steam plants of the utilities, it is estimated that 40,000,000 tons of coal more than were used would have been burned. The average efficiency of the country's steam generating stations in 1927 was 40% higher than in 1919, and while the production of electricity from fuel has increased 107% since 1919, the actual consumption of fuel increased but 19%. The U.S. Geological Survey states: "In 1927 the operators of the public utility power-plants performed the remarkable feat of generating 21 billion more kilowatt-hours of electricity with the use of 150,000 tons less fuel than in the previous year." In 1925 the United States generated 40% of all the elec tricity produced in the world, but in yearly per caput use of current ranked only fifth among the countries, according to figures presented at the Economic Conference, in Geneva, covering that year.

Norway, with a per caput consumption of 2,200 kilowatt-hours a year, led the world. Second came Canada, with 1,15o kilowatt hours. Switzerland was in third place with 990 kilowatt-hours. Others countries, in the order of their per caput use, were Ger many, France, Great Britain, Italy and Japan.

In production of electricity the United States had almost three times that of the next country, which was Germany, their totals being respectively 66 and 22 billion kilowatt-hours. Great Britain in 1925 produced 11 billion, and was followed by Canada, France, Italy, Japan, and Norway, in • that order. The figures for the United States and Canada cover only electric utility plant output, while for the other countries all generating plants are included. Of a total production by electric companies in the United States in 1927 of 75,116,000,00o kilowatt-hours, about two-thirds was produced by fuel burning plants, and one-third by water-power. There is available for development in the United States water power totaling approximately 5o million horse power, but it must be pointed out that a large part of the still undeveloped water power is not economically feasible under existing conditions of construction costs and markets and the severe competition of modem steam generating plants.

California ranks first among the States in public utility water power installations, with nearly two million horse power. New York, with 1,528,000 h.p., is second and the State of Washington, with 663,490 h.p., is third.

Use of Electricity.

The growth of interconnection and im provements in the art of electrical transmission and distribution is making electric service available to a steadily increasing num ber of villages and rural districts throughout the country. This flow of power is profoundly affecting American life, economically, socially and industrially.For a number of years after the establishment of the first cen tral station, electricity was used almost exclusively for lighting purposes. The earliest recorded use of an electric motor driven by central station power to do commercial work is about 1883, when a small motor is reported to have been set up in a grocery shop near the Pearl Street station and used to grind coffee. In 1927 electricity furnished 70%, or nearly three-fourths, of all the 41,000,000 h.p. used in American industry, and provided more than three horse power for every wage-earner. In 1900 there had been available only one-tenth of one h.p. per worker.

Between 1913 and 1928 the total electrical energy generated by the utilities of the country increased six times; the energy used for lighting increased six times, and that used for power increased eight times. Nearly 75% of the current produced is generated in the Atlantic and North Central States.

Despite the fact that the United States uses nearly as much electricity as the rest of the world, that country ranks only fifth in proportion of homes equipped for electric service. Switzerland is first, with 96.5% of her homes electrified. Japan, Denmark and Canada follow in that order, followed by the United States with 62% of her homes so equipped. Each of the countries lead ing the United States has large hydro-electric resources and rela tively short transmission distances to contend with, and most of their homes are in compact areas. There are more than million electrified homes in the United States, approximately as many as in the rest of the world, but tremendous areas of sparsely settled country have retarded the development of electric service therein. New York State has the largest number of electrified homes, with 2,550,00o, or more than 91% of the total number. Illinois and Pennsylvania follow, with about 1,450,000 each, and California is third, with 1,336,000.

Twelve per cent of the electricity generated by American utility companies is used for domestic purposes. This branch of the service produces approximately 3o% of the gross revenue of the electric utilities, but while the average domestic rate is 3.28 times the commercial rate, it is to be considered that the average com mercial customer is a wholesale purchaser, using more than 3o times as much as the average home.

Following the development of the electric incandescent lamp and the widespread establishment of central stations in the United States, small motors were perfected and the use of electric house hold labour-saving appliances began. It is impossible to obtain exact figures on the numbers of such appliances in use, but the following estimates, for 1927, are below rather than above the actual totals : Electric irons . . . . . . . . . . 13,500,000 Vacuum cleaners . . . . . . . . . 11,000,000 Clothes washers . . . . . . . . Electric fans . . . . . . . . . 4,600,000 Toasters . 4,500,000 Heaters . 2,300,000 Electric ranges 600,000 Electric refrigerators . . 500,000 Ironing machines . . . . . . . . . 350,000 These art the more widely used appliances for the home. A complete list would include dishwashers, radiators, sewing-ma chines, percolators, violet-ray outfits, heating pads, waffle-irons, hot plates, floor polishers, hair curlers, radio sets and many others.

High wages and increased purchasing power have made the American home the greatest user of electric appliances of any in the world. To the 171 million homes equipped for electric service, additional homes are being added at a rate of about 1 million yearly.

Rural Electrification.

The adoption by agriculture of elec tric power is a relatively recent development in the United States, and is playing a twofold part : first, by providing the farmer with a reliable, flexible source of power for farm work; and second, by providing the farm home with electric light and other mechanical comforts hitherto available only in towns.The increasing interconnection of utility systems, with their far-reaching transmission lines, has been a notable factor in rural electrification, in addition to which thousands of miles of rural lines have been built in farming districts. It is estimated that in 1928 there were 400,000 farms taking electric service from utility companies in the United States, about 6% of the total number of farms. Between 1923 and 1926 the number of electrified farms increased by 86.6%, at which rate there will be one million such farms in the country at the end of 1932.

California, where electric power is widely used for irrigation, leads the other States, having 62,000 farms served by the com panies. New York, with 44,000, is second, and the State of Wash ington, with 21,000, third.

Electricity in the farm home is used as in the urban dwelling, for light and to drive labour-saving appliances. Electric power for farm work is being economically used for a wide variety of purposes, among them : automatic water systems, baling presses, bone grinders, milk bottle washers, brooders, churns, cider mills, clippers and shearers, concrete mixers, corn shellers, cream sep arators, drills, fanning mills, feed grinders, hay hoists, incubators, limestone grinders, milking machines, potato graders, milk ref rig erators, saws, shredders, silo fillers, sorghum mills, sprayers, threshers and others.

Rural electrification in the United States is being hastened by the combined efforts of the utility companies, national and State Governments, through farm experiment stations and agricultural colleges, and other organizations. This work falls into two gen eral divisions : first, the application of electrical energy to present farming practices, and second, the development of new practices and farm equipment for which electricity may be peculiarly suited. Seventeen experimental rural lines have been built in as many States, and are serving as field laboratories. Information derived from their operation by utility companies, equipment manufacturers and agricultural experts is used both to avoid costly errors and to speed rural electrification to a sound and productive development.

Electricity in Industry.

It is probable that the appli cation of electric power to industry in the United States has been the single most important contributing factor in the past quarter-century to the country's material prosperity. Increased individual production, greater efficiency, higher wages and higher standards of living have followed this phase of electrical develop ment, and it is estimated that the American worker had in 1927 a real wage nearly double that of any in Europe.Between 1914, when the demand for war material stimulated American industry of every sort, and 1925, the output of Ameri can factories, mills, and other plants increased by 70%. During the same period the power used increased by 61%, virtually the entire increase being electrical. In this time the number of work ers increased only 21%, indicating the greatly augmented output per worker.

Significant changes in industrial operation appear in recent industrial electrification. Between 1919 and 1925 the use of primary power in the United States increased 22%, from 29,300, 000 to 35,775,000 horse-power. There was in this period almost no increase in boilers and engines installed in plants. The in crease of more than 6 million horse-power was practically all in electric motors driven by power furnished by electric utility companies.

It is estimated that there are installed in American industrial plants electric motors which in 1927 consumed more than 38 billion kilowatt-hours of energy, as compared to less than 20 bil lion kilowatt-hours in 1920. The cost of all power and fuel, the latter including fuel used to produce heat as well as power, is about 63% of the "value added by manufacture," and about 21% of the total value of the finished products.

Interconnection and the wide distribution of electric service has had a further effect upon American industry in liberating the manufacturing plant in its choice of location. The factory no longer has to go to a power source; power comes to it. With electric service to be had nearly everywhere, factories have been made free to consider other elements such as transportation facili ties, markets, availability of raw materials and labour. Thus small towns are increasingly often chosen as factory sites because of the better living conditions for the workers. Decentralization of American industry is becoming an actuality. The use of electric motors and power purchased from the utility companies obviates investment in boilers and engines by factories, and so releases large sums of capital for other purposes, and facilitates the estab lishment of new factories.

The most recent authentic figures upon the electrification of industry are those for 1925, completed by the U.S. Census of Manufactures. These indicate the following percentage of elec tric power used, in relation to all power, in various industries: machinery manufacture 95.7; transportation equipment, includ ing automobiles, 95.1; rubber products, 91.7; non-ferrous metals, 89.6; tobacco products, 87.1; leather products, 83.3; stone, clay, glass, etc., 80.4; textiles and their products, 74-6; food and kin dred products, 65.7. The average for the 16 major industries examined was 7o% of electrification, a proportion which has since then materially increased. These industries had installed motors aggregating more than 25 million horse-power, of which nearly 16 million horse-power were supplied by energy purchased from the electrical utilities, and the rest by generators in the plants.

Finance.