Electrostatics

ELECTROSTATICS The electrostatic unit of elec tricity is defined to be a quantity such that, when placed one centi metre from an equal quantity, in a vacuum, it repels with a force of one dyne. The force in dynes between two charges, e and e', at a distance of r centimetres apart, in a vacuum, is equal to dynes. The force between charges in air, or other gases, is practically equal to that in a vacuum.

The region near electric charges, in which there is a force on a charged particle, is called the electric field of the charges. The charges are said to excite a field in the space around them. The strength of the electric field is defined to be the force in dynes, per unit charge, on a charged par ticle put in the field, and the direction of the field is defined to be the direction of the force of the charged particle. The strength of the electric field at a point is also called the electric intensity at the point.

The electric intensity at the surface of a conductor, in which the electricity is at rest, is in a direction perpendicular to the surface of the conductor, be cause otherwise there would be a component of the intensity along the surface, which would set the electricity in the conductor in motion. The electric intensity inside the material of a conductor is zero, in electrostatics, because otherwise a current would be produced in the conductor.

Lines of Force.

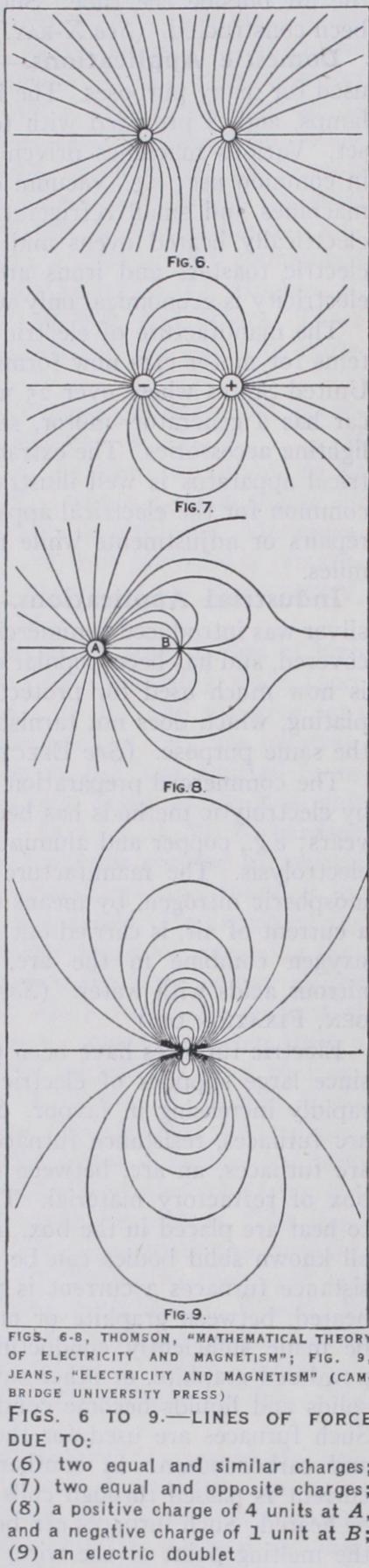

A line of force, in an electric field, is a line drawn so that its direction is everywhere along the direction of the field. The lines of force due to a charge at a point are straight lines drawn in any direction from the point. The electric intensity at any point due to two or more point charges may be obtained by finding the resultant of the forces on a charged particle at the point, due to the point charges. Each point charge is supposed to exert the same force on the particle as if the other point charges were not present. If we use rectangular axes, x,y,z and if X,Y,Z are the components of the electric intensity, then, if dx, dy, dz are the components of a displacement ds along a line of force, we have dx/X = dy/ Y = dz/Z, because the resultant of X, Y and Z is along ds.The lines of force due to two equal and similar charges are shown in fig. 6, and the lines of force due to two equal and op posite charges in fig. 7. Fig. 8 shows the lines of force due to a positive charge of 4 units at A and a negative charge of one unit at B. Fig. 9 shows the lines of force due to two large equal and opposite charges, near together, which form what is called an electrical doublet. Lines of force start from positive charges and end on negative charges. They cannot cross each other, since the intensity can have only one direction at any point. The lines of force map out the electric field, and a careful study of them enables one to form a much clearer conception of the distribution of the field.

Gauss' Theorem.

Let a closed surface S be drawn anywhere in an electric field, in a vacuum, and let there be a charge e at a point P inside it. Consider a small area a on the surface at A, and let PA =r. The field A, due to e, is along PA. Let AN be drawn normal to the surface at A, and let the angle between AN and PA produced be 0. Describe a sphere of unit radius, with P as centre, and draw lines from P to the boundary of the area and so as to mark out a cone with vertex at P, of which a is a section. Let this cone cut off an area w on the sphere of unit radius.The normal section of the cone at A is acos6, so that w = since the section of a cone is proportional to the square of the distance from the vertex. Also so that e = and ew = = aFcos9. Fcos9 is the component of F along the normal to a. Denoting this component by N, we have Na = ew. Now suppose the whole closed surface S divided up into small areas like a. Let the areas be .... Let N,, N3, ... be the normal components of F at the areas, and let col, ... be the corresponding areas cut off on the unit sphere. Then we have = = N3a3 = Adding all these equations, we get LL N1a1+N2a2+N3a3+ • • • = W3+ • • • )• But wl+w2+w3+ ... will be equal to the area of the surface of the unit sphere, or 47r, so that, finally, N1a1+N2a2+ ... = 4rre, which may be written LNa = 4ire.

If there is another charge e' inside the closed surface we shall have in the same way LN'a = 4rre'. The total normal components of F due to both charges will be etc., so that, if we now let N denote the total normal component of F, we get ZNa = 47r(e+e') . If there is any number of charges inside the closed surface, then ZNa = 47rZe, where Ze denotes the sum of all the charges inside. The field due to negative charges is in the opposite direction to the field due to positive charges, so that in calculating le the numerical values of the charges are to be reckoned positive for positive charges and negative for negative charges. This theorem is due to Gauss and it is funda mental in electrostatic theory.

Tubes of Force.

The meaning of Gauss' theorem may be made very clear by means of what are called tubes of force. Take a small area in an electric field and draw lines of force through a great many of the points on the boundary of this area. Since lines of force never intersect, these lines will enclose a tube shaped volume in the field, which is called a tube of force. Let P and Q be two points in a tube of force, and let a and a' be the cross sections of the tube at P and Q, and let F and F' be the electric inten sities at P and Q. Apply Gauss' theorem to the closed surface made up of the two sections at P and Q and the part of the tube between them. The normal electric intensity is zero over the surface of the tube, so that ZNa reduces to Fa—F'a'. If there is no charge inside the tube then Z e = o, so that we have Fa = F'a'. Thus it appears that, along any tube of force, the product of the electric intensity into the cross section is constant. The cross sections of the tubes of force are at our disposal, since we can draw as many of them in the field as we choose. Let us then suppose the whole field divided into tubes of force, and let the cross sections be made equal to 1/F, so that the number of tubes passing through any area drawn perpendicular to the field is equal to F. The product Fa is then equal to unity for every tube. Such tubes, for which Fa= i, may be called unit tubes. The number of unit tubes passing through any small area in the field is equal to Facos9, where 0 is the angle between the normal to the area a, and the direction of the field F; for acos° is the area of the projection of a on to a plane perpendicular to F. If then N denotes the component of F along the normal to a, so that N = Fcos0, we see that Na is the number of unit tubes passing through the area. Gauss' theorem, I Na = 41r e, therefore means that the number of unit tubes of electric force coming out of a closed surface is equal to the total charge inside multiplied by Orr.

Tubes of force start on positive charges and end on negative charges. At the surface of a conductor where the tubes start or end, the tubes are perpendicular to the surface. Consider the charge on the area of a conductor from which a tube of force starts. Imagine the tube produced a short distance into the conductor, and consider the part of the tube between a cross section just inside the conductor and another one just outside. Apply Gauss' theorem to this part of the tube, and let the area of cross section be a. If s is the charge per unit area on the con ductor, or the surface density of the charge, then the charge inside is sa. There is no field in the conductor, and the field outside is along the tube, so that ZNa = Fa, where F is the field strength just outside the conductor. Hence we have Fa = 4irsa, or F = 4Trs. For a unit tube we have a = I/F = 1/47rs.

Many of the facts of electrostatics discussed in the historical introduction can be easily shown to follow from Gauss' theorem. Consider a solid conductor of any shape, and apply Gauss' theorem to a surface drawn anywhere inside the surface of the conductor. There is no electric intensity at this surface if the electricity in the conductor is in equilibrium, so that ENa = o, and therefore Ze =o. Thus we see that, however strongly the conductor is charged, there will be no charge anywhere inside it, so that all the charge resides on its surface.

Now consider a hollow conductor bounded by two closed sur faces, one inside the other. If we imagine a closed surface drawn in the conductor between its inside and outside surfaces, and apply Gauss' theorem to this surface, we see that the total charge inside a closed hollow conductor is zero. Thus, for ex ample, if a charged conductor is put inside the hollow conductor, there must be an induced charge on the inside surface equal and opposite to that on the charged conductor, as in Faraday's ice-pail experiment. If the hollow conductor were insulated and uncharged when the charged conductor was put inside it, a charge would appear on its outside surface equal to the charge put inside, because the total charge on the hollow conductor is zero.

The electric field outside a charged sphere is the same as if the charge on it were concentrated at its centre. For, if we describe a spherical surface of radius r outside the sphere and concentric with it, we see, by symmetry, that the field will be normal to this surface and uniform over it. Let the field be F, so that, by Gauss' theorem, /Na = = 47re, where e is the charge on the sphere. Thus as if the charge were at the centre.

Potential Difference.

When a charged particle is moved about in an electric field, work has to be done against the forces on the particle. If an amount of work, W, is done on the system consisting of the charged conductors and the particle, when the particle is moved from a point A to another point B, the poten tial energy of the system is increased by W, and this energy can be got out of the system by allowing the particle to move back to B, doing work W as it moves back. The work required to move a charged particle from one point A to another one B in an electrostatic field is the same for all paths between A and B. For if not, the particles can be moved from A to B along one path and then back to A along another path, giving back more work, so that a supply of work could be obtained in this way without using up the energy of the system, which is impossible.The potential difference between two points in an electric field is defined to be the work, in ergs, required to take a charged particle from one point to the other, per unit charged on the particle. The charge on the particle must be so small that it does not appreciably alter the field when it moves. The potential of the earth is usually taken to be zero, for convenience, in which case the potential at any point is equal to the work in ergs re quired to take a charged particle from the earth to the point, per unit charge on the particle.

Consider two points A and B very near together in an electric field of strength F. Let the angle between AB and the direction of F be 0. Then the work to take a unit charge from B to A is equal to F. AB• cos9, so that the potential difference between A and B is given by PA - PB = F. AB. cos°, so that Thus we see that the component of the electric intensity along any direction is equal to the space-rate of decrease of the poten tial in that direction; e.g., if denotes the x component of the electric intensity, and P the potential, then = —3P/ ax.

The potential difference, due to a charge e, between a point at a distance r from the charge and a point at a great distance away is equal to e/r. The force on a unit charge at a distance r from the charge e is so that the work done on the charge by the field, when r is increased from to is between and If and are very nearly equal, either of these expressions is equal to — or to If then ... are successive values of r as it is increased, each one only slightly greater than the previous one, the work done on the unit charge as r increases is which is equal to when the final value of r is very large. Thus the work obtained, when a unit charge is moved from a distance from the charge e, to a great distance from it, is The potential difference between a point at a distance r from the charge e and points at a great distance away is therefore equal to e/r. If the potential at a great distance away is taken equal to zero, which is often convenient, then we may say that the potential due to a charge e, at a distance r, is equal to e/r. This result may be obtained also as follows. If P denotes the potential, we have = — aP/ar, so that d P = — which, on integration, gives P = constant. If we suppose P = o at r = oo , therefore the constant = zero and this becomes P = e/r.

The potential at a point due to any distribution of charges is therefore equal to E(e/r), which denotes the sum of each element of charge divided by its distance from the point. This result is true only when the potential at a great distance is taken to be zero. It is not true, for example, when the earth is taken to be at zero potential. Since the electric field inside the material of a conductor is zero, in electrostatics, it follows that no work is required to move a charged particle from one point in a conductor to any other point in it, so that the potential must be the same throughout the conductor. If two or more conductors are con nected together by conducting wires, they are then parts of one conductor, and so are all at the same potential. Conductors connected to the earth are at zero potential, when the earth is taken to be at zero potential.

Capacity.

The capacity of a conductor is defined to be the charge required to give it unit potential when all other conductors near are at zero potential. A system of two conductors separated from each other by a thin layer of insulator is called a condenser. The charges on the two conductors are usually approximately equal and of opposite sign, and the capacity of the condenser is then taken to be equal to the positive charge divided by the potential difference between the conductors.To find the capacity of a conductor it is necessary to find its potential and its charge when other conductors near are at zero potential. Consider a conducting sphere of radius a with no other conductors near. We have seen that the electric field out side a charged sphere is the same as if the charge were concen trated at its centre. If the sphere has a charge e the potential outside it is therefore equal to e/r, and so is equal to e/a at the surface of the sphere. The sphere therefore has a potential e/a when its charge is e. Its capacity is therefore equal to e divided by e/a, or to a. The capacity of an isolated sphere is therefore equal to its radius.

Next consider a sphere of radius

a surrounded by a concentric thin hollow sphere of radius b. Describe a spherical surface of radius r between the two spheres (see fig. Io.) Apply Gauss' theorem to this surface. If F is the field at its surface we have = 47re, where e is the charge on the inner sphere. Hence F = so that the potential difference between the two spheres is equal to e/a—e/b. The capacity of the inner sphere is therefore equal to e divided by e/a—e/b, or to i/(I/a — i/b) = ab/ (b— a) . The capacity can therefore be made large by making the two radii nearly equal. The capacity of the outer sphere can easily be seen to be ab/(b—a)+b, or The capacity of a condenser consisting of two equal parallel metal plates at a small distance d apart can be easily calculated approximately. If the potential difference between the plates is P then the electric intensity is P/d. The electric intensity close to the surface of a charged conductor, in the direction away from the surface, is equal to ors, where s is the surface density of charge. Hence, if s is the surface density on one plate and s' that on the other, we have 47rs = P/d, and 47rs' = — P/d, so that s = —s'. The capacity per unit area is s/P, or I/47rd. This is the capacity between the plates at a distance from the edges. Near the edges the field between them is not uniform, and so is not equal to P/d.

Force on Surface of Charged Conductor.

The field F, close to the surface of a conductor on which the surface density is s, is equal to ors, and just inside the surface it is equal to zero, so that the average field acting on the layer of charge is the force on unit area of the surface is therefore equal to Fs/2. This result may be obtained in another way as follows :—The field F may be regarded as made up of two parts, due to the layer of charge on the conductor, and F2, due to other charges at a distance. Just inside the conductor the field is reversed in direction, and the total field is zero, so that and therefore so that = F/ 2. The force on the surface layer is equal to because the field due to the charge s cannot be supposed to tend to move it. Hence the force on unit area is Fs/2 or which is equal to T.

If there is a potential difference

P be tween two parallel metal plates at a dis tance d apart, then they attract each other with a force 71- per unit area, or since F = P/d. The potential dif ference between the plates can therefore be found by measuring the attraction and the distance d. An instrument for measur ing potential differences in this way was designed by Lord Kelvin and is called Kel vin's absolute electrometer. Instruments for measuring potential differences depending on the electrostatic attraction between a movable conductor and fixed conductors are called electrostatic voltmeters. The gold leaf electroscope may be used as an electrostatic voltmeter, if it is provided with some device for measuring the divergence of the leaves, and cali brated. The quadrant electrometer is an electrostatic instru ment by means of which potential differences as small as one millionth of an electrostatic unit of potential difference can be measured. (See INSTRUMENTS, ELECTRICAL.) Specific Inductive Capacity.—So far we have been supposing that the insulator between the conductors was a vacuum or air. It was found by Faraday that the capacity of a condenser de pends on the nature of the insulator between the plates; e.g.

with glass between the plates instead of a vacuum, it may be

Io times as great. The ratio of the capacity of a condenser, with the space between the conductors completely filled with an insulator, to the capacity with a vacuum between the plates is called the specific inductive capacity of the insulator. It is denoted by K which is thus taken to equal unity for a vacuum.

Since the capacity is increased

K times by the presence of the insulator it follows that, for a given charge, the potential dif ference, and therefore also the electric intensity between the conductors, is diminished K times. For example, in the case of a condenser consisting of two concentric spheres of radii a and b, the electric intensity between the spheres will be instead of where e is the charge on the inner sphere and r the dis tance from its centre. We have seen that in vacuo we can divide the field into unit tubes of force, starting from positive charges I/47r and ending on negative charges —1/47r. In the same way we can divide the field between the two spheres in the medium of specific inductive capacity K into unit tubes of force, each starting from a charge I/47r on the inner sphere. The num ber of these tubes will be 47re, so that the cross section a of a tube at distance r from the centre will be given by a = The intensity F is equal to so that KFa = 1. Thus, in this special case, we see that, along the unit tubes, KFa = I, instead of Fa = I, as in a vacuum.

In Faraday's ice-pail experiment, if pieces of any insulators,

for example sulphur, glass and wax of any size and shape are put in the can, the experiment works in the same way as before. This shows that a charged conductor induces an equal and op posite charge on a hollow conductor surrounding it whatever the nature and distribution of the insulators in the space between the two conductors. This suggests that the number of unit tubes passing through any closed surface surrounding a conductor with charge e on it is equal to ore, whatever the distribution of insulators in the space around it.

Generalization of Gauss' Theorem.

We therefore assume that, in any case, KFa = I along a unit tube, and that the number of unit tubes coming out of a charge e is ore. With these assumptions we can obtain the generalization of Gauss' theorem, which is true for any distribution of insulators between the conductors. Consider a closed surface of any shape, and let A be a small area on it. Let the electric intensity at A be F, and the specific inductive capacity K. Let the angle between F and the outward drawn normal to A be 9. The cross section of a unit tube at A is a = I/KF. The projection of this on A is a/cos9, or I/(KFcos6), so that the number of unit tubes, passing out through A, is A divided by I/(KFcos9), or AKFcosO. Let Fcos9 = N, so that A KFcos9 = KNA . The total number of unit tubes passing out through the closed surface is therefore ZKNA, and this is equal to 47rZe, so that we get ZKNA = 47rZe as the generalization of Gauss' theorem. The results deduced from this are found to agree with the facts, so it is believed to be correct. If we apply this generalized form of Gauss' theorem to a small rectangular block, with its edges parallel to rectangular axes x, y, z, we find that a (KF.) + a (KF„) a = 47rp, ax ay az where F„ and are the components of the electric field along directions parallel to the axes, and p is the density of electric charge inside the block.