Hieroglyphs

HIEROGLYPHS.) Foreign Influence.—Under the r 8th Dynasty we find the first real differences from the classical civilization of the Old and Middle Kingdoms, owing to the conquest of the country by Semitic foreigners, the Hyksos, and the conquest of Hither Asia by the Egyptians that followed their expulsion. This event modified Egyptian culture profoundly, and sowed the seeds of its degeneration. The foreign influences, Asiatic, Cretan, Libyan, grew ever more potent to affect the externals of Egyptian culture, though the religion (except during the ephemeral revolution of Ikhnaton), and the writing maintained their characteristic form, and preserved the individual nationality of the people.

Archaism, the Last Phase.

Under the Saites, mental revolt against the foreign elements, and against Asiatic contamination generally, combined with antiquarian interest in their own most ancient monuments at Memphis and its neighbourhood, brought about the archaistic movement that sought to imitate the old classical period, and more especially its earlier phase, that of the pyramid-builders. There was a definite archaistic revival in art, but its neo-classicism hardly deceives us. It is always an in accurate imitation ; the scientific archaeologist of to-day was yet unknown. Still, the effect is often beautiful, and is eminently characteristic. And the archaism went much further than the realm of art. It did not, however, save Egypt, which went down before the Persian ; and when the Macedonians established a new Egyptian empire in Asia, a new imperialist archaism set in, which strove to imitate the works of the Thutmosids and the Ramessides, the imperial style of the i 8th and i9th Dynasties, but with less success than the Saite archaizers. The spirit of Egypt was going; she was dying. The Egyptian culture of the Roman epoch was but a miserable parody.

Modern Critical Study.

So archaeological study has taught us to distinguish the characteristics of the successive ages of Egyptian history, to trace its development from age to age. Although Egyptological knowledge without archaeological study, based on excavation, could enable us to possess a superficial knowledge of the process, it is only within the last thirty years that, thanks to modern archaeology, we have been able to pursue our study into minute details. The comparison of the numberless records of scientific observation in excavation has now enabled us to do this, and we can now date objects of Egyptian culture to their proper periods without any royal inscription to help us. It is cumulative evidence that has told. And in the case of Egypt we can do so with more certainty than in the case of any other ancient people, the Greeks not excluded. With one characteristic exception, the figures of the gods. Here we can rarely tell the date of, say, a bronze Osiris, unless he is inscribed or we know with what objects he was found. The gods did not alter. And the dress of the kings was in early days nearly as immutable. But under the i 8th Dynasty they had begun to wear a headdress unknown before, and under the i 9th Dynasty they begin to be represented in the clothes they really wore, as well as in their hieratic 5th Dynasty costume. But to tell the date of an un inscribed royal figure of the "classical" time is difficult, unless we are well versed in niceties of artistic criticism, which in the case of Egypt has nowadays made great strides, so that the critic can argue that an Egyptian statue must or cannot be of the i 2th Dynasty on grounds of style alone, and often with success and accuracy.3. History of Egyptian Art: the Pre-dynastic Period.— The beginnings of Egyptian art antedate the arrival of the "Dy nastic Egyptians" from the north. We see them in the curious painted pottery figures of mourning women, standing or seated on the ground with their arms raised, and with their bodies decorated apparently with tattoo-marks, which are found in early pre-dynastic graves (a fine collection is in the British museum), in tusks of ivory with carved heads of long-bearded men, in a few crude scratched representations of animals on the early red and black pottery, and in the geometric and (rarely) animal-figure designs in thick white slip-paint on red ware. Combs of ivory with male heads, and figures of animals follow, and slate palettes in the form of animals, such as hippopotami, hyenas, bats, tortoises, fish and cuttlefish, on which face-paint was ground for use. Then come the pictures of men, women, goats, cattle and boats in thin red paint on the buff ware. These figures are not in outline and cross-hatched, as in the earlier white and red ware, but are solid. Male figures are rarer than female. The men are naked. The representations of boats are very curious, and with one or two exceptions are extremely unlike boats, so much so that they were formerly often taken to be pictures of stockaded village-settlements, the oars being the stockade, the cabins the houses, while the "totem-poles" with figures of animals would be appropriate to both conceptions. It seems, however, that we must regard them as boats. Then come the first wall-paintings with very similar scenes, as at al-Kab, in which we find the men wearing now the characteristic Egyptian waist-clout of white linen. The colours used are red, white and black. To this time probably belong the rude gigantic figures of the god Min from Koptos, in the Ashmolean museum at Oxford, with their reliefs of goats on hills.

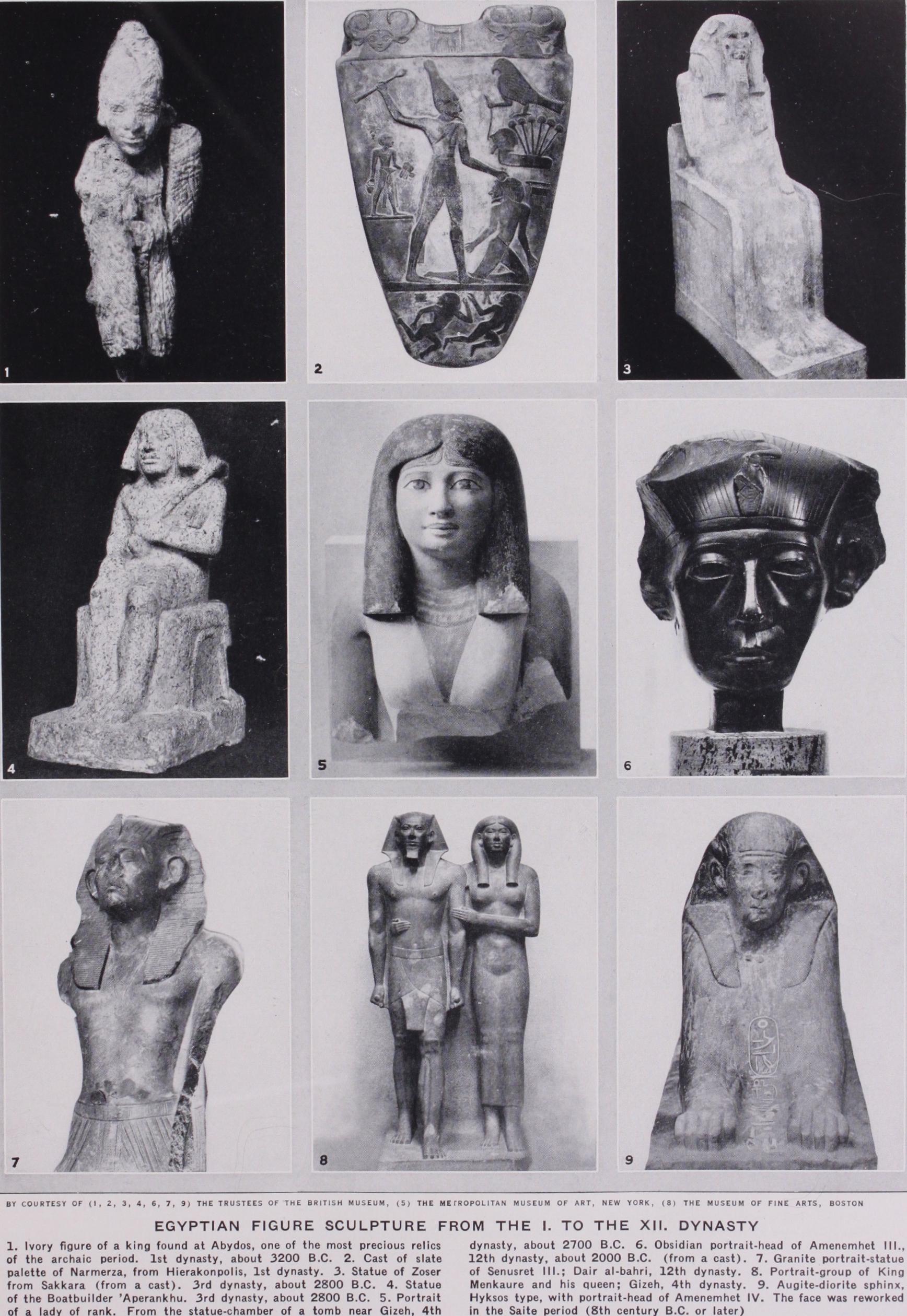

As the conquest by the people of the North continues we find the level of art rising swiftly. The flint weapons are at their finest, the technique of stone-vase making rapidly improves, gold decoration begins to be used, as for instance on the handle of the famous flint knife from al-Araq. But pottery deteriorates. It would look as if the improvement in stone vessels meant less interest in the finer kinds of pottery. Stone and gold-work attract most attention. Stone sculpture begins in rude flat relief figures on limestone grave stelae. A parallel with contemporary Sumerian art is found in the sculpture of processions of animals, generally sheep, goats or cattle ; no doubt these were intended to ensure continuance of riches in flocks and herds in the next world. The slate paint-palettes develop into large objects with a circular ring-depression for the paint, and are decorated with most lively scenes in low relief of hunters, armed with bows and arrows and throwsticks pursuing lions, and of the corpses of the dead in battle being cast out to be devoured by vultures (British museum. Louvre). Other such fragments show ostriches (Brit. mus.), giraffes with a palm tree (Ashmolean) ; on another (Brit. mus.) is the earliest hieroglyph known, the symbol of the god Min, while on the British museum fragment of the large "hunt-palette" is the hieroglyph of a chest, the sign of "burial." The Archaic Period.—These works herald the beginning of the Dynastic Period, when we find a strongly marked upswing of artistic capacity. Progress is specially marked during the first five reigns, of Narmerza and `Ahai (who with the pre-dynastic Southern king and first conqueror of the North were probably together the originals of the legendary "Menes"), of Zer, Za and Den. We know the work of this time well from the discoveries at Abydos, Hierakonpolis, Tarkhan and Turra. A typical example of this progress is seen in the one instance of the figure of the hawk, typifying the king, above the serekji or "proclaimer" banner containing the name of the king, now written in genuine hiero glyphics which we can interpret. This hawk-figure develops in a most interesting way, till after the end of the reign of Den it takes on its characteristic form, which it has finally assumed by the end of the dynasty. And in order to appreciate not only the advance that was made during the early dynasties, but also the remarkable strength of conception and power of design in the work of the beginning of the r st Dynasty we may compare reliefs of the 3rd and 4th Dynasties with the chef-d'oeuvre of the archaic period, the remarkable slate "palette" of Narmerza from Hierakonpolis (Cairo museum; casts in the British museum and the Ashmolean), on which we see in relief "Menes" attended by his sandal-bearer, inspecting the bodies of his slain Northern enemies, while the hawk of his Upper Egyptian tribal god Horus seizes a strange half-human figure emblematic of the North : above, the queer fetish-heads of the cow-goddess Hathor, which we already know in the pre-dynastic period, seem to typify the union of the two races that was producing Egyptian civilization. The great ceremonial mace-heads of the Scorpion and Narmerza, also from Hierakonpolis (in the Ashmolean), commemorating the Scorpion's conquest of the North and the Jubilee festival of Narmerza also show very interesting reliefs. "One is struck by the naive energy of this commemorative art, which has preserved for us a contemporary record of the founding of the Egyptian kingdom." In ivory we have (Brit. mus.) the extraordinarily lifelike little figure of a king (No. 37,996) wearing the crown of Upper Egypt and a long and very foreign-looking patterned robe of a kind that we never see a king wearing later, which was found by Petrie at Abydos. It is probably the most precious relic of the archaic period.

Den-Semti was the first to bear the afterwards time-honoured title of "Insibya" or king of Upper and Lower Egypt, and in his time the first moment of crystallization in the development of art and culture occurred. After his time the tempo slows down; originality becomes rarer, crudities begin to be thrown aside. At the same time luxury increases noticeably. From the relics found in his tomb, or cenotaph, at Abydos we see already a rich and picturesque civilization, energetic and full of new ideas, both artistic and of a more practical character. Gold and ivory and valuable wood were lavishly used for small objects of art, fine vases of stone were made, and the wine of the grape (irp) was kept in great pottery vases stored in magazines like those of the pithoi at Knossos. The art of making the blue glaze "fayence," that typically Egyptian art, which had already been invented in pre-dynastic times, developed very much at this time. The king's jewellers made wonderful bracelets of gold and carnelian, sceptres of sard and of gold, and so forth. The king's carpenters "could make furniture of elaborate type; the well-known bull's hoof motif for chair-legs already appears." And they could make the interesting little labels of ivory and wood on which were inscribed the events of the king's reign, with incised representations of him smiting his enemies (Brit. mus.). Wood was imported for large and small work, for beams or for year-labels, into woodless Egypt from Syria already, no doubt by sea. It was used con siderably in building in conjunction with brick, for the art of stone building had not developed much yet ; that progress was reserved for the next age. Pottery had deteriorated badly since the pre-dynastic age. It is an interesting fact that elsewhere, in Babylonia and in Crete, for instance, the pottery also degen erated at the opening of the age of metal. It was still built up, made without the wheel, which hr.d not yet reached Egypt from Babylonia.

Possible Babylonian Influence.—The question of Baby lonian influence on the nascent Egyptian culture and art is inter esting and important. We see undoubted traces of it in many things, chief among them the style of building brick walls, which are simple reproduction of the Sumerian style, with its recessed panels, in everything but the shape of the brick, which in Egypt is always rectangular and long, never either plano-convex or a flat square, as often in Babylonia. It looks as if the crude brick had been invented independently in Egypt, as it naturally might be in a land of mud, but that the panelled style of building with bricks came from Babylonia. Again, the use of stone (and wood) seal-cylinders at this time in Egypt, and also of the peculiar conical macehead, points to Babylonian influence. A reverse in fluence, of Egypt on Babylonia, is improbable, because in Baby lonia at least the first of these things were at home, and were there to stay, whereas in Egypt they were not destined to last, the use of the seal-cylinder indeed being comparatively ephemeral there. Then there are the Babylonish-looking monsters on slate palettes, which disappeared from Egypt with the 1st Dynasty, the similar processions of animals in both arts at this time (al ready mentioned), and the identical early representation of the lion with open grinning jaws and round muzzle in both countries; already by the time of the 3rd Dynasty the Egyptian had dropped him and evolved his own dignified lion with closed mouth, whereas the Babylonian retained his own furious lion to the end of the chapter of his art. These things, and others, are important to note, especially now that we seem to be compelled by the latest discoveries at Ur to recognize the superior antiquity of Sumerian art. If Babylonia was the senior we could understand that she contributed something to the feverishly accumulating make-up of the young Egyptian culture, some of which was afterwards dropped. But there is the question whether the com munication was direct, or whether the fact was that both Egypt and Babylonia received certain similar elements of culture from a common source, which must have been in Syria. We do not yet know. The "dynastic Egyptian" who came from Syria probably brought certain elements of culture thence; besides developed agriculture and the connected Osiris-Isis worship, also probably the knowledge of copper, and probably the conical macehead, and possibly the panelled style of building. But other foreign elements seem later, and to be contemporary with the union of the kingdom; and it must be remembered not only that more or less direct communication with Babylonia through the Hauran and so across the desert was then possible as later, but that in all probability direct sea-communication existed between such ports as Qusair, at the sea-end of the Wadi Hamamat, and the ports of Southern Babylonia. The evidence of the al-`Araq knife with its gold-beaten handle-reliefs of foreign ships and a Baby lonish-looking god is evidence of this even in the pre-dynastic period; and we know that in all probability Kagan, "the place to which one goes in ships," from which the Sumerians derived some of their hard stone (unobtainable in their own country) was the Eastern Desert of Egypt and possibly Sinai.

However this may be, the two cultures very soon took each its own line of development, and Babylonia, at least, was never in fluenced in the smallest degree by Egypt except possibly at one single period, that of the Sargonide kings of Akkad (c. 2 700 B.c.) when a peculiar style of sculpture was in use that recalls the work of the early Egyptian dynasties more than anything else in tech nique, though the subjects show no sign of Egyptian influence.

The Epoch of Imhotep.—Under the long 2nd Dynasty we have little to record; a static period succeeded the dynamic 1st Dynasty. But with the advent of the short-lived 3rd, a new dynamic period set in suddenly with a political explosion. A new king from the South, Kha`sekhem, dispossessed the successors of Menes, who had taken up their abode in the conquered North, and as king of both countries called himself Kha`sekhemui ("Appear ance of the two Powers" instead of "Appearance of the Power"). His statue in the Ashmolean Museum, from Hierakonpolis, tells us that he took 47,209 Northerners captive, and on its base we see, summarily cut in outline, variously contorted figures of the slain. Evidently the twisted attitudes of their bodies were admired and sketched at the time, and were reproduced by the king's sculptor on his statue-base. "It was an age of cheerful savage energy, like most times when kingdoms and peoples are in the making." The statue of the new Menes however did not mark a very great advance on former work, though it was bigger; the lifesize figure was to come in the next reign, which marked a climacteric in the history of Egyptian art and science. His son Zoser (Tosorthros) was probably one of the greatest of the early pharaohs ; at any rate he was served by one of the greatest of Egyptian ministers, the wise Yemhatpe or Imhotep, who was later deified under his own name (in Ptolemaic days pronounced Imouth, the Imouthes of the Greeks), as the god of knowledge and especially of medical science the Egyptian Asklepios. He is depicted as a priestly man, seated, reading a scroll open on his knees. Imhotep was not only a physician, he was also an architect, and it is more than probable that the extraordinary architectural development that marks the reign of Zoser was due to his inspiration and teaching. He was certainly not deified for nothing, and when we find that it was in the reign of the king whose minister he, the divine patron of science, was, that a sudden and unparalleled advance in art and architecture was made, we can hardly err in attributing this advance to him. It was always recorded that it was in the reign of Tosorthros that "the first stone house was built," as we read in Manetho ; and the most ancient Egyptian pyramid, the "Step Pyramid" at Sakkara, was built by Zoser. No such great stone building was known before. And now Mr. Firth has revealed at Sakkara the original 3rd Dynasty funerary temple of the king, with the serdab, or recess, in which his lifesize statue (the oldest) was placed at his death and found by Mr. Firth; and it is more than likely that the royal tomb itself may be reached. And the most extraordinary thing about this temple is its architecture. It has panelled walls of fine limestone, and lotus-columns of the same beautiful oolite stone, long corridors of them; the work is the first of the developed Egyptian style which we know henceforth till the end. It has been said that such "style" means a long previous development through stages unknown to us. But yet there seems to be no time for any such development. In the work of the 1st Dynasty there was nothing like this. The conclusion seems un avoidable that this was a sudden development due to a single brain, that of the wise Imhotep, or to two brains, if Zoser is to be given a share of the credit. And such sudden developments do occur from time to time in history; such powerful brains do some times appear, and bend things to their superior will. We have later instances in the history of Egypt itself, notably that of Ikhnaton, though his work was impermanent. We are too apt to assume "long periods of development." Nature does not do things per saltuyn but man does. He sometimes creates specially, as Imhotep seems to have done. At any rate, in the absence of any evidence of any such previous development, we seem justified in assuming so.

It was not only in architecture that the creative genius, whom we have supposed to have been Imhotep, showed his hand. In re lief sculpture also the style that had already appeared in the memorials of the 1st and 2nd Dynasty kings on the rocks of Sinai now developed into the first examples of the historic Egyp tian style, with the king depicted in the manner in which we see him henceforward ; though it was not stereotyped till the time of the 5th Dynasty. Sculpture in the round remains more archaic in type, with curious human faces reminding us of certain extra ordinary sculptured heads hitherto usually attributed either to the Hyksos or to the gth Dynasty (at Cairo), which may however themselves be of the 3rd. The portrait-statue of Zoser is some what of this type, and the figure is distinctly archaic still. Sculp ture in the round was not to take its final form till the next dynasty, the age of the great pyramid-builders.

The Pyramid-builders.

The impulse given to architectural development in Zoser's reign pushed on swiftly in less than a cen tury after his death to the achievement of the most colossal buildings in Egyptian, if not in all human history, the Great and Second Pyramids of Gizeh, the tombs of the kings Khufu (Cheops) and Khafre` (Chephren) of the 4th Dynasty. The wonderful height attained in the sphere of mathematics and en gineering, as well as design, which is attested by these two great buildings, has always struck the imagination of mankind.At this time begins the long series of private tombs decorated with reliefs representing the dead owner amid his daily surround ings, with his wife and family, hunting or overseeing his estates, and with his fellahin engaged in their daily avocations. The royal tombs themselves are not yet decorated in any way: but their fu nerary temples, close by, were, chiefly with religious scenes. At the same time sculpture in the round assumes its final form in the statues of the kings Khafre` and Menkaure`, the latter with his queen and with the goddesses of the "nomes" or provinces of Egypt, among the greatest treasures of the Boston and Cairo museums. We now see in the faces of the kings the first examples of the Egyptian genius for personal portraiture which later became one of the chief and most valuable characteristics of Egyptian art. Another portrait-figure of the time is the well-known "Skeikh al balad." And in the famous statues of the Prince Ra'hotep and his wife Nefert (also at Cairo), with the amazing lifelike effect of their eyes, produced by the means of a pin of copper representing the iris inserted into a crystal eyeball, we have a startling combination of accurate portraiture and appearance of life. This technique of eye-representation was often repeated in Egypt later on, in glass or obsidian, as well as crystal. It was paralleled contempo raneously in Babylonia, by means of shell for the white of the eye and jasper for the cornea, but not so successfully. Wood-carving is exemplified in the beautiful reliefs of the panels of Hesire` at Cairo. Pottery improves, a fine bright red polished ware coming into use, that continued till the time of the 7th Dynasty.

Under the sth and 6th Dynasties the pyramids deteriorate, and are largely composed of rubble with facing of limestone, whereas the great pyramids of the preceding dynasty had been made of the finest limestone blocks throughout. The actual tomb-chamber of the king now begins to be decorated with religious texts, the "Pyramid-Texts," spells relating to life in the next world calcu lated to secure the safety of the dead monarch there; precursors of the chapters from the "Book of the Dead" of a later epoch (see Religion) . The funerary temples on the other hand are magnifi cent, built with great papyrus-columns of red granite and deco rated with fine reliefs in which the official religious style is now fixed. Tomb-reliefs and portrait-statues continue excellent. Stone vases have become smaller and more delicate; under the 5th and 6th Dynasties beautiful unguent pots of alabaster (calcite) were often placed in the tombs.

Under the 6th Dynasty we have the magnificent statues from Hierakonpolis of king Pepi I. and his small son in copper (not bronze, as used to be thought owing to a mistaken analysis), at Cairo. The copper was apparently beaten, not cast, though this is not quite certain in the case of the head of the prince. Here we have a technique that first comes to our knowledge now, though it was probably older, since we have a record of a copper statue having been made of king Kha`sekhemui under the 3rd Dynasty. It is probable that this art came to Egypt from Babylonia, where we find it in the case of the great copper reliefs and figures of animals found at al-`Ubaid, near Ur, which date to about 3100 B.C., and are presumably contemporary with the 2nd Dynasty owing to the usual computation, but before the 1st if we adopt that of Scharff.

The Middle Kingdom: 9th to 12th Dynasty.

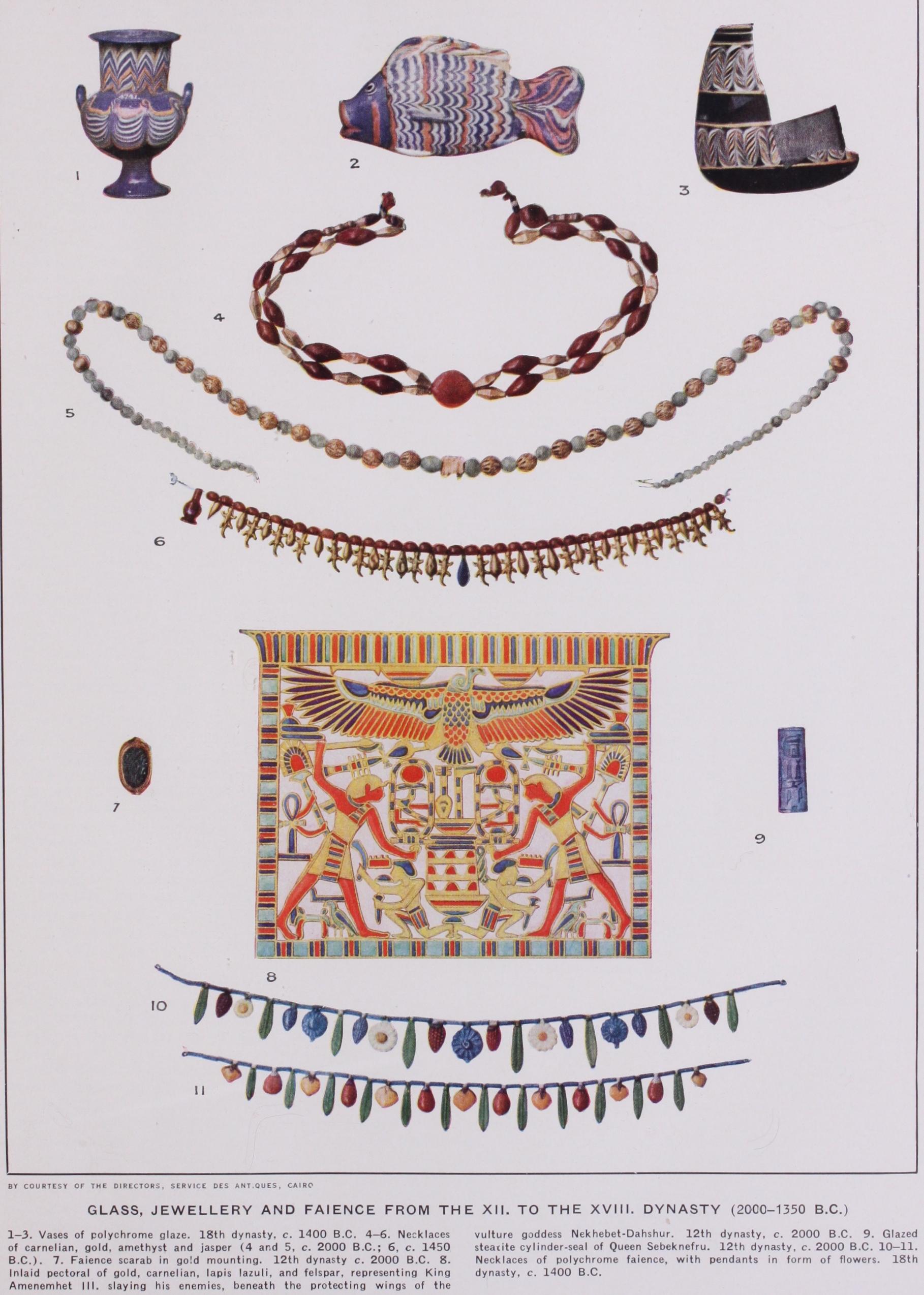

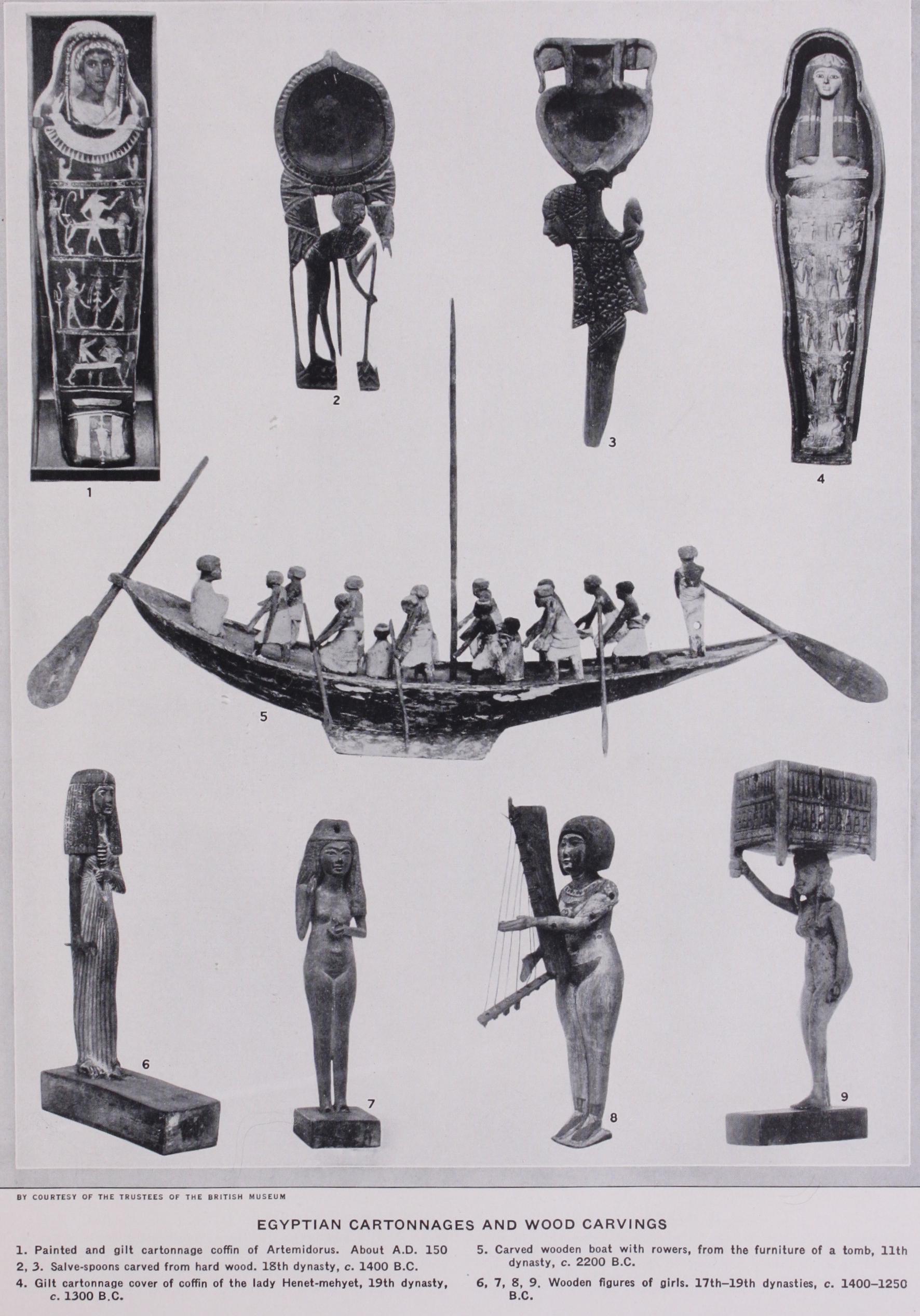

At the end of the dynasty, art, which had been slowly deteriorating for some time, temporarily disappeared in a welter of civil war and possibly foreign invasion, both of Semites from the North and Nubians from the South. Under the Herakleopolite kings of the gth Dynasty it reappears, but under the first Thebans of the 11th is still of a rude and clumsy character, especially in its reliefs, until in the settled and prosperous reign of king Mentuhotep III., who reunified the distracted country, a sculptor seems to have arisen, named Mertisen, to whom is probably due the artistic renascence of the Middle Kingdom. His work is to be seen in the sculptures of the king's funerary temple, Ikh-isut, at Dair al-bahri, discovered by Naville and Hall in 1903 (Brit. mus.) . These reliefs and figures are still a little crude, but give ample promise of the fine art to come. In the reign of Amenemhet I., the first king of the 12th Dynasty, we find a very delicate style of relief. Under Senusret I. sunk relief (cavo rilievo) is used at Koptos, under Senusret III. (Sesostris) is seen splendid vigour of portraiture in the grey gran ite royal statues from Dair al-bahri and the red granite head from Abydos (Brit. mus.), which becomes magnificence in the famous portraits of Amenemhet III., especially in the small obsidian head, formerly in the Macgregor collection, which is probably he, and is a marvel of style and workmanship in so intractable a ma terial as well as, evidently, a faithful portrait of the original. Another small portrait, in serpentine, which is certainly Amen emhet, was in the Grenfell collection, and now belongs to Mr. Oscar Raphael. The small statue of him as a young man, at Leningrad, is also well known (casts of all three in the Brit. mus.). A sphinx now in the British museum, recently presented by the National Art Collections Fund, magnificently carved, shows us the hitherto unknown features of his son Amenemhet IV. The treat ment of the mane of this sphinx, in short lion's locks, is precisely similar to that of the manes of the so-called Hyksos sphinxes from Tanis at Cairo which are, on this new authority, definitely to be dated to this period and no doubt present portraits of Amenemhet III. Tomb reliefs now are uncommon, and the wall decoration is usually simply painted in tempera.The small arts of ivory carving, of fayence-making, of gold and electrum work, and of cloisonné inlay in beautiful stones such as carnelian, lapis, turquoise and blue felspar, of scarab-making in glazed steatite, obsidian, crystal and amethyst, are all now at their apogee. Nothing so tasteful, so well proportioned, so grace ful, so delicate was made later. The figures of the royal princesses from Dashur and Lisht are of beautiful workmanship. Scarabs at this time came into general vogue. They had been used at the end of the Old Kingdom and made of blue glaze, without inscription, but with the labyrinthine designs common at the time on small seals, especially on a class known as "button-seals," probably of foreign origin, and usually made of ivory or steatite, which is closely paralleled in early Minoan Crete. From the 9th to the i 2th Dynasty the scarab develops with characteristic spiral de signs of Aegean (and possibly ultimately of Sumerian or of Central-European) origin, and under the i 2th inscriptions are added; it begins to be used as a seal. When inscribed its material was usually of glazed steatite; scarabs of the harder stones were generally not themselves inscribed, but often bore an inscription on a gold, electrum or silver plate cemented to the base. Twelfth Dynasty scarabs are among the finest known, both for design and beauty of glaze (see also SCARAB).

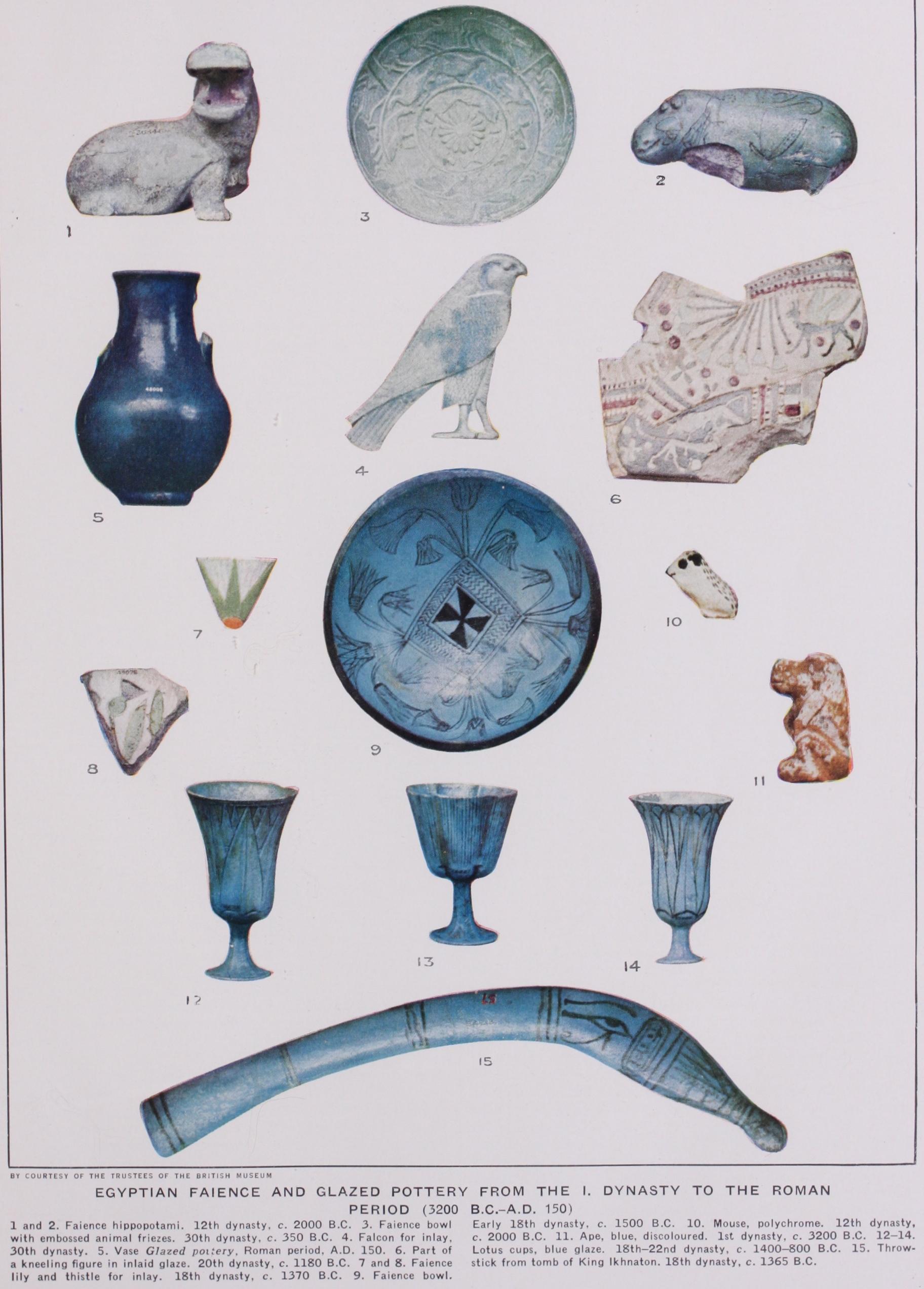

A quaint, often crude, but also often finely executed art of the period from the 6th to the r 2th Dynasty, is the making of the little model figures of people at work in the fields or the granaries, ploughing, winnowing, etc., also of boats with their rowers, con veying the funeral cortege across the Nile, which were placed in the tombs at this time. (See Religion.) Ivory carving was a specialty of this dynasty, very character istic being small seated male figures, like the wooden ones, often with inscriptions or spiral designs on the base. Small figures of this kind were characteristic of the time also in other materials, especially blue fayence; and magnificent small examples of figures of animals in this material, especially of hippopotami, with the water plants amid which they lived, painted in manganese black on their sides, are in the chief museums. The fayence has now largely abandoned the original pale blue colour of the Old King dom for a splendid deep blue. Ordinary pottery has now de teriorated again, the fine polished red ware of the Old Kingdom disappearing. Stone vases continue to be fine, especially those of alabaster and of a peculiar blue marble very popular at this time for unguent-vases or alabastra.

Thirteenth Dynasty and Hyksos.

Under the i3th Dynasty deterioration once again set in. The great school of sculptors cannot keep up the standard of Amenemhet III.'s time. Royal statues become curiously lanky and attenuated; faces and necks get long, heads disproportionately small, as in the Sebekhotep in the Louvre. The finest work of the time (early in the dynasty) is the head, long attributed to Amenemhet III. (and formerly to Apepi the Hyksos) from Bubastis in the British museum. From the form of the headdress and other characteristics I would at tribute this work to the i3th rather than the i2th Dynasty. The king whose portrait it is is unknown. But things never get so bad as they were between the 6th and 9th–I 2th Dynasties. The I 2th Dynasty taste in small objects continues, though workmanship falls short of the old distinction. A newly developed art is that of coffin-decoration. Until now the dead had been placed in great rectangular chests, at first with little ornament but a bare in scription, then under the i 2th Dynasty finely and simply deco rated without with bands of inscription, and often within with maps of the underworld to guide the soul, pictured lists of the amulets and sacred unguents buried with him, and funerary spells of power. In this under the i 2th Dynasty the mummy was often placed with a human-face cartonnage mask over its head. In the following period the rectangular chest was given up (probably owing to growing difficulties of obtaining suitable wood from Syria) and an outer coffin of poor native wood was sub stituted with a human head like that of the inner mask, and with body roughly shaped like a swathed mummy. In the case of some of the kings the body of the coffin was painted with the vulture feathers of the protecting goddess, so that they are known, from the Arabic word, as rishi coffins. Henceforward the human headed coffin was the rule (see Religion), and an enormous number of artists (of high and low degree of capacity) must have been employed at all times in making, painting and gilding them.

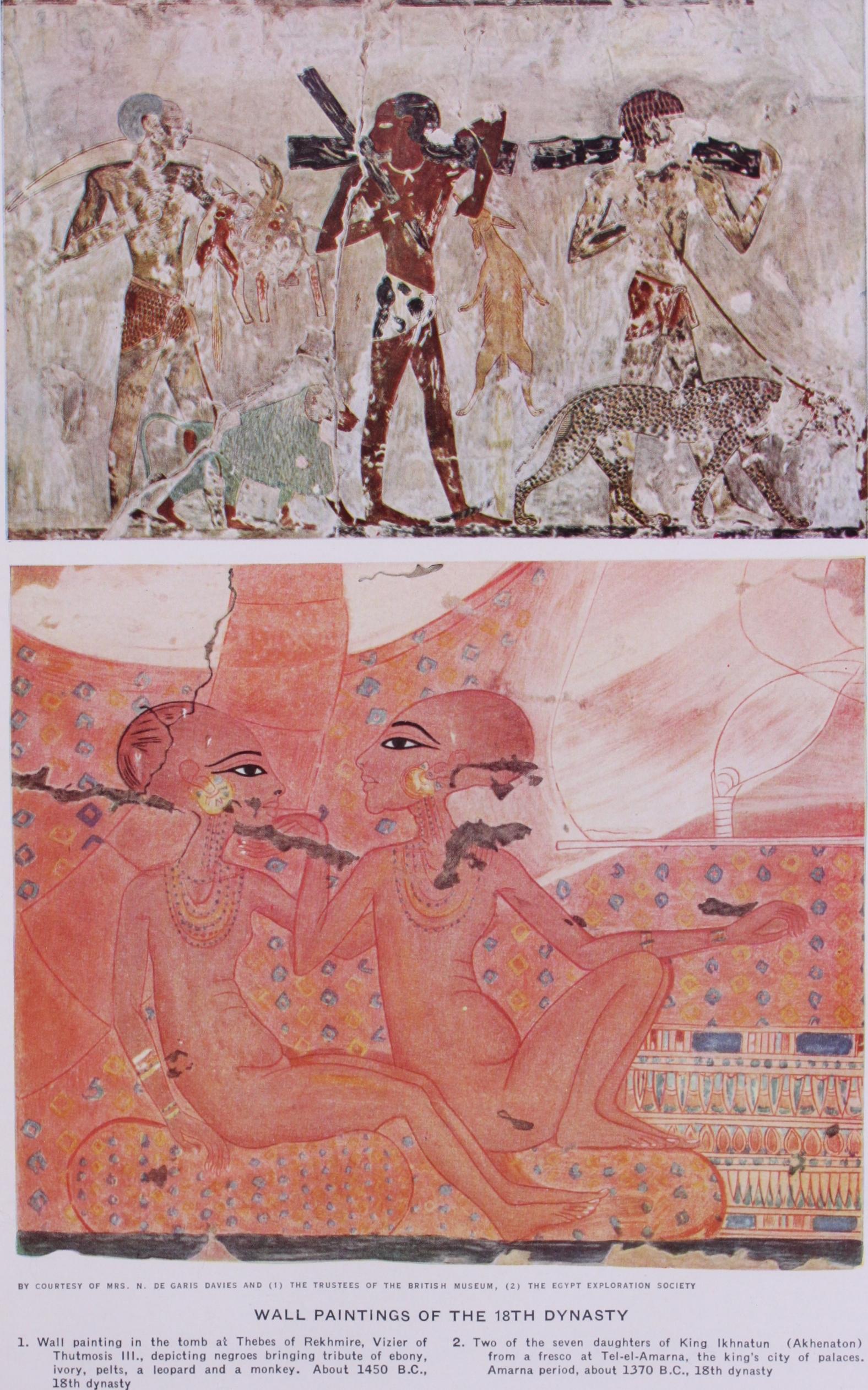

The New Kingdom: 18th

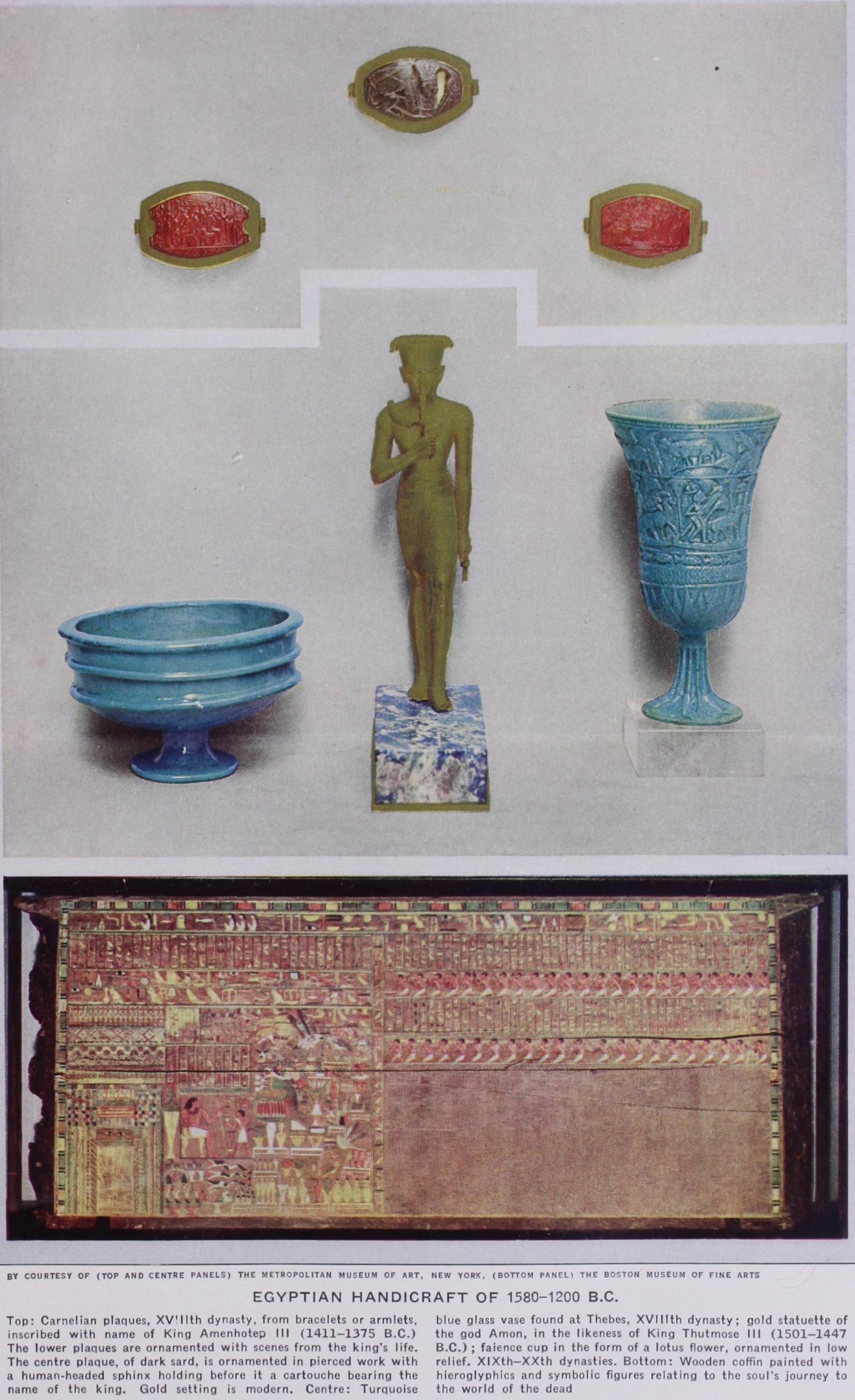

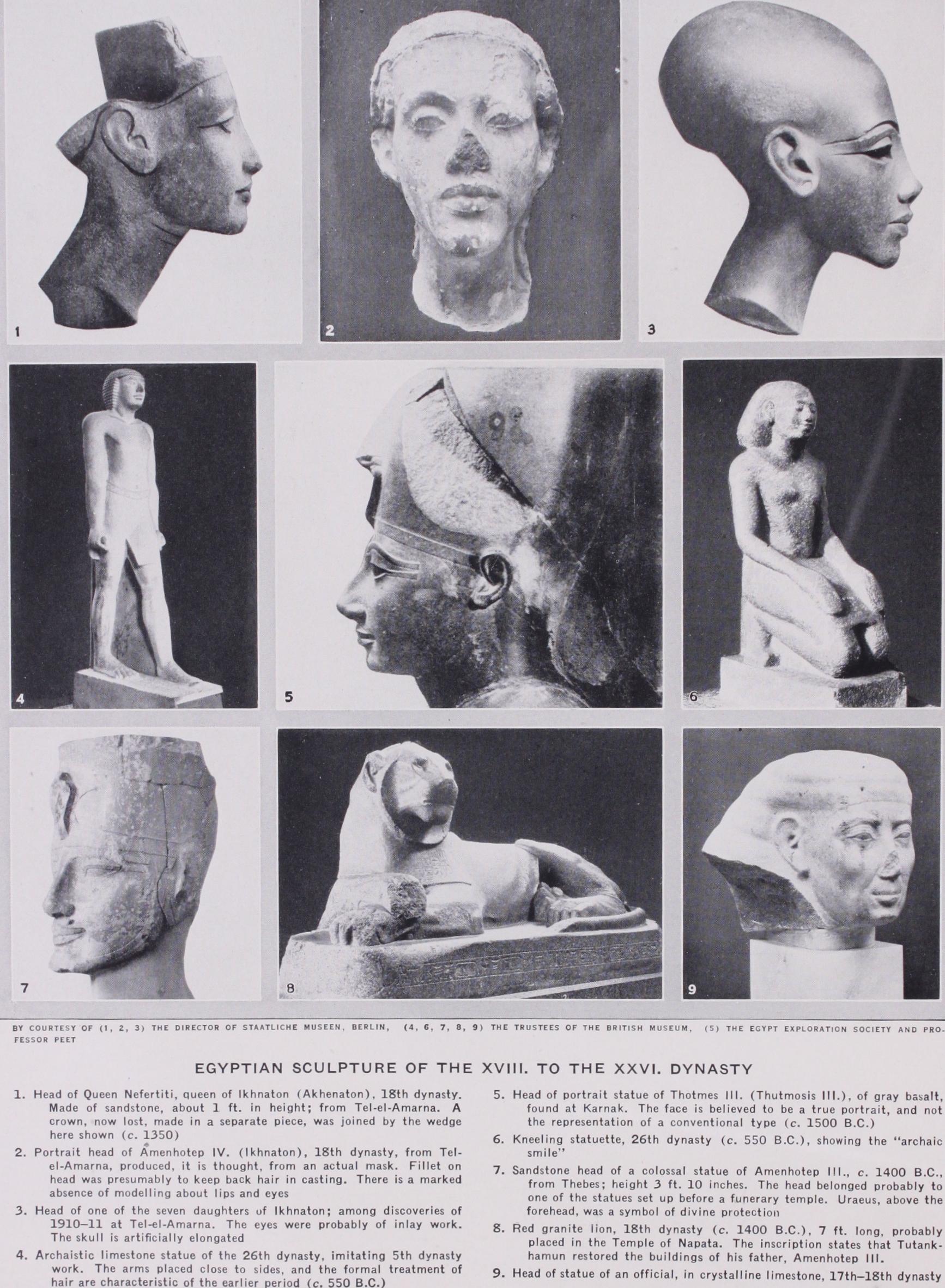

Dynasty.—Under the i8th Dynasty a new renascence begins, with a new note of a hitherto unknown tone. A wave of Asiatic conquest had overflowed Egypt, and had retreated, but it had left its marks. The art of the first two reigns of the new dynasty of "Liberators" bears strong traces of close relationship to that of the 12th-13th Dynasties, but in the reign of Thutmase or Thutmosis I., the first to carry Egyptian arms into Syria to avenge the Hyksos conquest, the new element appears, which is due to foreign Syrian influence. Such things as the chariot (see below) were directly adopted from Asia with the advent of the horse and weapons add to their number such a purely Asiatic form as the curved scimitar or khepesli, previously unknown, and certainly adopted, like the chariot, from the Hyksos. In the reign of the conqueror Thutmosis III. we are in the full tide of the great civilization and art of the i8th Dynasty, and we see in it unequivocal traces of the foreign influ ence, which increases as time goes on. In the reign of Amenhotep III. it is specially strong, but at the same time in no way domi nant or able in reality to denationalize Egyptian culture and art at all. The old Egyptian traits, especially in the all-embracing domain of religion, are as strong as ever. But where religion could not penetrate, the loss of character due to foreign connections is evident. The new art, like the new culture, is beautiful, but it is lavish, its taste is not so good as was that of the i 2th Dynasty, it is rococo.In architecture we do not see any very great development of previous ideas. We know very little of the temple-buildings of the I 2th Dynasty, as they were mostly rebuilt in later days, but it is probable that the i8th Dynasty introduced few new im provements on them. Even so original a building as Queen Hat shepsut's terrace-temple at Dair al-bahri is now known to be merely an enlarged adaptation of the older temple of the I i th Dynasty at the side of which it was built. The old tradition of adorning them with the statues of the kings who built them is carried on, with the same care of portraiture, and with a greatly developed tendency to gigantism, which began under the 12th Dynasty when the first colossi were produced. The colossal head of Amenhotep III. in the British museum is one of the finest Egyptian portraits existing. The extremely unbeautiful, but prob ably lifelike, colossal heads of Ikhnaton, lately discovered, are evidence that the colossus-convention was retained by him. Among smaller royal portraits the young Thutmosis III. at Cairo is one of the finest known ; it is unusually unconventional in treatment for the time, and no doubt a good likeness. A more conventional head, probably of the same king (but by some con sidered to be more probably his sister Hatshepsut) in the British museum, shows how the royal features could be toned down and regularized for an official portrait. Votive statues of private per sons show the same regularized portraits, but very often they are as true as under the i2th Dynasty, as we see from the famous figures of the sage minister, Amenhotep son of Hapu, at Cairo. The groups in white limestone of a man and his wife seated, side by side, which were either placed in the round in tombs or sculp tured in high relief in the rock at the end of the tomb-corridor, are very characteristic, and show the costume of the new age with careful accuracy. For costume had now altered and de veloped in a way unknown since the beginning of the Old King dom, though the change was in no way so radical as those known in Europe. There was, however, now an added note of grace in men's as well as women's costume, that contrasts greatly with the stiffness of the dress of the older dynasties (see Dress). Tomb-decoration for private persons of distinction consists chiefly of wall-portraits in distemper depicting the same scenes of daily life as before, to which great men add pictorial records of the honours they have received from the king, or of events of their time redounding to the honour and glory of their royal master, such as the reception of foreign ambassadors and tribute-bearers from Asia and from Greece. The tomb of Sennemut, the architect of Queen Hatshepsut, of Rekhmire`, the vizier of Thutmosis III., and of Menkheperre`senb, another great man of his time, are cases in point. In them we see pictures of the reception of Minoan ambassadors from Crete which are among the most important historical records of their time. In the reign of Amenhotep III. relief decoration comes into fashion again for tombs, as it had always been used in the temples. The delicate colour reliefs of the temple at Dair al-bahri, depicting Queen Hatshepsut's expedition to the land of Punt (Somaliland) are among the finest earlier works of the dynasty. Later on we have such fine work as that in the tombs of Khaemhe`t and Ramose at Thebes. The royal tombs do not yet show the elaborate painted decoration, repre senting scenes in the next world, so characteristic of the i9th and aoth Dynasties, and do not yet approach the extensive plan of those of the later time. Amenhotep II.'s is the finest, and is decorated with restraint. Tutenkhamon's tomb is but a sepulchre, with little wall-decoration and that unfinished.

The actual objects buried with the king are of unparalleled magnificence. In his case not only specifically funerary objects were buried with him but also, apparently, most of the things that he had actually used in life, his chairs, clothes, boxes, lamps, chariots, sticks, weapons, rings, amulets, necklaces, etc., and it is probable that much the same thing was done in the case of every deceased monarch. But only Tutenkhamon's has ever been found intact, though we have previously found objects, fewer in number, but of almost equal magnificence and interest, in the tomb of Iuya and Tuyu, the grandparents of King Ikhnaton whose successor Tutenkhamon was. These things enable us to form a picture of court life in the fourteenth century B.C. in Egypt more complete than that which we possess in the case of any other ancient civilization. Archaeological excavation has told us more of ancient Egyptian life than that of any other an cient nation. For details of the various wonders of ancient art that Tutenkhamon's tomb has revealed the published accounts of this find must be consulted. But little has been revealed by it that was actually unknown before. The forms, the motives, the types of decoration were all known. But we often find them in new and unprecedented combinations, especially in the royal jewellery, which shows how sumptuously the old 12th Dynasty tradition of gold and semi-precious stone inlay was carried on. The taste, however, is now not so good. The newer art is some times rather garish and vulgar, as seen in many other objects from Tutenkhamon's tomb such as, more especially, the great alabaster or calcite vases represented as on imitation wooden stands of alabaster and combined with the twining papyrus and lily-stems e7nblematic of South and North ; the conception is forced and ugly. Calcite vases with coloured lions on their lids look as if they were made of sugar and were intended to be eaten. Bad taste is beginning to creep in. But on the other hand we also see the characteristics of the new free conception of art intro duced by Amenhotep III. and Ikhnaton in the representations of the young king with his consort on the back of a chair, or the almost Persian miniature picture of a lion-hunt on a box. For eign influence we see too in such work as that of the king's iron and gold daggers, with their non-Egyptian type of hilt and gold filigree decoration.

The Amarna Period.

In the reign of Amenhotep III. a new impulse towards freedom in art was given, in conjunction with the movement towards new thought in religious matters, which culminated in the monotheistic cult of the Aton or sun-disc, pro claimed by his son Ikhnaton (see Religion). For a time Egyp tian art seemed to be about to cast off its age-long shackles, and, had the religion of the Aton endured, this would have happened. The removal of the religious bonds would have led, probably, to an extraordinary development of art, and at the same time have altered the whole course of Egyptian civilization. But this was not to be; and after only a few years, in the reign of Tutenkh amon, in fact, king and people returned to polytheistic ortho doxy, and history resumed its course on the old lines. It was in fact impossible to alter the religion of the whole nation, and we see that in spite of all his efforts, Ikhnaton was unable to de flect the Egyptian mind more than a very little out of its accus tomed ways. In the art of his time, of which we have recovered so many magnificent examples from the ruins of his city of palaces at al- Amarna, the old motives of religious origin still persisted. There is nothing radically new in the most daring innovations of the disc worshippers; only the representation of the sun-god him self, as a disc with rays terminating in hands holding the symbol of life, is entirely new. The old clichés go on in use, and after all they were beautiful, extraordinarily decorative. They were pre served. In sculpture in the round we see the new striving after truth in such a wonderful portrait as the coloured stone head of Queen Nefertiti at Berlin, in which all ancient convention seems to have been dropped : even the eyes are painted naturalistically, with none of that curious antique convention of representation that had persisted since the days of the 1st Dynasty and was to reassert itself very soon. Of the sculptor's desire for truth we have a proof in the extraordinary series of plaster masks, taken from living and dead faces, and from statues, found with the Nefertiti head in the "House of the Sculptor" at Amarna. They were part of his stock-in-trade to be used for portrait-figures. We see new ideas in the representation of the home-life of the royal family, shown with a freedom unprecedented; for the first time Egyptian royalties are human. Ikhnaton offers his wife a flower; Amenhotep III. leans forward heavily and lazily, arm over knees, as he sits on his throne, even in a formal sculpture ; Tutenkhamon and his wife are shown affectionately conversing. But the setting remains the same and the technique cannot alter, and above all Ikhnaton cannot change the hieroglyphic writing, in which the whole ancient history of Egypt's religion and art are enshrined. The protest could not last ; and when the priests of Amon gained the upper hand, after the king's death, it was not long before all the ephemeral beauty of Ikhnaton's art disappeared. Tutenkh amon's tomb had a few things of his style; after all, he had only been a few years dead. But after the long reign of the conserva tive reactionary Horemheb nothing remained of the beauty that Amenhotep III. had envisaged and Ikhnaton had for a moment carried into effect, than a certain delicacy of workmanship in the reliefs of Seti I. at Abydos and the swan-song of fine Egyp tian art—the beautiful statue of Rameses II. at Turin.Small art shows the old characteristic of freedom in all things non-religious. Alabaster vases are specially beautiful; the jug shape, previously unknown, comes into use, and the globular bodied, high-lipped vase on a high foot. Scarabs alter very much in type, green glaze comes into vogue, fayence becomes a favour ite material, and in the first half of the 15th century the blue fayence is extraordinarily beautiful. Later on, under Amenhotep III., polychrome glazes are introduced, and all sorts of vivid shades of blue, violet, yellow, chocolate, apple-green are used, which are characteristic of the Amarna period. This polychromy arose from the new polychromy of glass. Under the lath Dynasty real glass, as opposed to glaze, appeared for the first time. It was at first plain blue ; but about the time of Thutmosis III. the art was discovered of making the wonderful opaque poly chrome glass vases that are among the most beautiful and most valuable contents of our Egyptian museums. The first produced were somewhat heavy and coarse, but very soon a remarkable lightness of handling was obtained. A particularly beautiful pale blue is characteristic, and an imitation of obsidian or black glass is excessively rare. Combination of all these materials with gold is common. Gold is lavishly used. "Gold is as dust in thy land, my brother," writes the king of Babylonia to Amenhotep III. Tutenkhamon had a solid gold coffin. And no doubt other kings had solid gold coffins also. Gold is used very freely in conjunction with wood, especially in furniture and in chariots. The arts con nected with chariot-wheel making and horse-trappings generally are new in Egypt at this time, as the chariot and horses were not introduced from Asia till the time of the Hyksos, about i800 B.C. previously the Egyptians had not employed wheeled vehicles at all, but sledges, and asses for draught. Bronze is now in regular use for weapons, and iron comes into more general use but is still precious and worthy of kings.

The Ramessides and the Decadence.—Under the kings of the 19th Dynasty the degeneration sets in. Gold is too much to the fore and is becoming vulgar. Growing vulgarity is the note of the age. The long reign of Rameses II. saw a progressive decline of the arts. We find a grandiose conception of Tutenkhamon's architects at Luxor imitated by Seti I. in a still more grandiose conception, the great Hypostyle hall at Karnak. But it is too big; too gigantic. It is coarse and clumsy. And this coarseness is seen in all the arts after the death of Seti. There is only one good statue of Rameses, that at Turin. The rest are either abominable, or else are not really his but are stolen from former kings. The great rock-cut temple of Abu-Simbel is an atrocity, with its great lumpish clumsy figures, everything out of propor tion, everything all wrong. The huge royal tombs are imposing, with their pictured halls showing the adventures of the soul in the underworld. But their painting is often coarsely executed. Relief is now, after Seti's low-relief work at Abydos, generally sunk, in cavo-rilievo, an old Egyptian idea not much in favour under the i8th Dynasty. Now we find it employed for the amaz ing scenes of royal wars that covered the outer walls and pylons of the temples in which the king, of an enormous size, slays hordes of foreign enemies. He had done this before, on a smaller scale, in art as far back as the time of the 1st Dynasty, but now he did it on the heroic scale. And the style is almost barbaric. Private tombs, excavated as before in the hillsides, show a progressive degeneration of the 18th Dynasty decoration.

In small art vulgarity progresses, but not so blatantly. Many beautiful small things of art were made under the 19th Dynasty, of faience, of alabaster and other stones. The fine alabaster vases of the 18th Dynasty continue, often with handles in the form of animals; but forms deteriorate. The blue faience is not quite so good ; polychromy continues in duller, dirtier tints. Red stones come into use, such as jasper, Bard and carnelian to the exclusion of blue, though blue stones of Asiatic origin, like lapis or chalcedony, were rather favoured. Asiatic influence becomes more and more marked; Semitic gods, Semitic names and Semitic ideas appear upon the monuments.

Under the loth Dynasty the pace of the deterioration increases, especially after the reign of Rameses III. Temples become hideous rows of sausage-pillars with hieroglyphs a yard high, miracles of bad taste. Gold becomes gilding, and it is everywhere ; vulgar dis play hides growing poverty of idea. There is nothing new, there is nothing distinguished now. Tomb-reliefs are stereotyped; even the old power of portraiture has gone. Under the 21st there is a short Indian summer of art at Thebes; almost a pathetic attempt at a revival of lost beauty. The blue faience is startlingly deep in colour; something had been recaptured here. But it is too harsh a blue, and the modelling it covers is worthless. The art of coffin making which had developed in the direction of complexity of re ligious ornament from the simple inscription bands of the 18th Dynasty is now very elaborate. The yellow-varnished coffin of the time, with their relief decorations and inscriptions in gesso, are well known. We have a very inter sting relic in the embroidered "funeral tent" of the Queen Isimkheb, which has been eclipsed as an example of an Egyptian luxury-textile by the older robe (?) of woven linen tapestry of Amenhotep II., found in the tomb of his son Thutmosis IV. We know that the Egyptians used em broidered linen in great variety (though little of it has come down to us) from the paintings. The national art of linen-making is of course characteristic of all periods from the pre-dynastic, when it first appears, though it may have been at its finest under the 11th and 12th Dynasties.

The Archaistic Renascence Under the Saites.—With the 22nd Dynasty everything becomes bad, poor and dull; it is the nadir of Egyptian art. Under the 25th however in the North a new spirit arose in the 8th century. The monuments of the pyra mid-builders in the vicinity of Memphis attracted the attention of the artists, and a new school of sculptors arose at Memphis characterized by a curious archaism. The style of the ancient statues and reliefs was adopted, often directly imitated. Notables of the new time were shown wearing, not their real clothes, but the plain loin-cloths of the 5th Dynasty, combined with the round wigs they usually wore; just as in the 17th and i8th centuries our worthies were often represented in Roman armour with wigs. Sometimes, as in a statue at the British museum, the archaism extends to the wig, so that but for the inscription it would hardly be possible to tell that the statue was not of the 5th Dynasty. The writing could not be archaized very much, though attempts were made in that direction. At Thebes something of the old imperial art-tradition remained, and there we see a neo-Theban school, with a touch of the Memphite archaism in it, which produced some re markable work in the 7th century, notably the portrait heads of the princes Nsiptah and Momtenhet and the unknown old man in the British museum (No. 37,883). Here the native genius for por traiture again shines forth after its eclipse since the loth Dynasty, and throughout the 26th Dynasty it persists, and later, till it again dies out under the Ptolemies. The Saite archaism was eclectic.

and we can often diagnose it by its mixture of the characteristics of historically different periods, such as the Pyramid-time and the 12th Dynasty. It appealed to the Egyptians of the seventh century as appropriate to the new course in national history which was now entered on after the emancipation from Assyrian conquest under the Saites. The old imperial order .constituted with such splendour under the i8th Dynasty was dead, and men turned for new inspiration to the ancient days of the pyramid-builders, before Asia, taken captive, had corrupted her conquerors and planted in them the seeds of decay. The result in the domain of art, as in other things, was the creation of an artificial simplicity and juven ility which, however, was by no means without beauty. The Saite sculptors were wonderful workers of the hardest stones, and their work in basalt and granite, combining the simplicity of old days with the delicacy and style that was wholly new, is characteristic of their period. In small art we see a conscious return to ancient ideas in the abandonment of the dark blue fayence for an imita tion—a most delicate and beautiful imitation—of the pale blue of the Old Kingdom. This pale blue faience, well exemplified in the ushabti-figures of the time, so well known in our collections, is characteristic. Scarabs and scaraboids were beautifully made of fine stones; the Saite engraver was a master. But it was not only in small things that the Saite artist excelled. He made very big things too, such as the huge monolithic shrines in the temples, equally characteristic of the period. Tombs were now built very often with a certain archaism, in the form of huge brick buildings above the actual chambers of the dead hollowed out of the rock below ; this was in some sort a return to the mastaba of the Old Kingdom, and a rejection of the hillside cham ber-tombs of the 12th and 18th-2oth Dynasties. Tomb reliefs im itate those of the 5th Dynasty, with a difference that does not escape the modern critical eye. And as time goes on we see this difference accentuating itself in a way that we cannot mistake ; it is being influenced by the renascent Greek art of the 6th and 5th centuries. Already under Apries and Amasis we see Egyptian figures adopting a curious simpering smile, which we can hardly fail to attribute to the influence of Greek archaic art, commun icated through the medium of Naukratis, of Daphnae and of Cyprus. This "archaic smile" which was natural to the young Greek art, was unnatural and artificial in Egypt, and was adopted there merely as a preciosity. It continued all through the Ptole maic period in Egypt, and became characteristic of the work of that age. Conversely, Egyptian archaistic figures influenced the early Greek sculptors in their figures of Apollos or victors in the games. In the 5th and 4th centuries Egyptian tomb-reliefs and vase-decorations show definite imitations of the new mature Greek art grafted on to the archaistic Saite style. The age of the last native kings is still in its art Saite, but of a curiously delicate re fined character to be carefully distinguished from the larger style of the 26th Dynasty.

Ptolemaic Art.

Under the Ptolemies there is another change. Foreign conquest again became familiar under the successors of Alexander, and from a finikin imitation of Old Kingdom models men turned to gross and wooden imitations of the imperial style again in temple-reliefs and in statuary. All art became gradually worse; the Saite delicacy was soon entirely lost, what there was of grace and beauty in the first Ptolemaic century disappeared at the end of the period. The roughness of the sculpture in coarser soft sandstone shows an incredible decadence, which was only emphasized under the Romans. The small arts degenerate con formably, but more slowly. The pale blue glaze continues under the Ptolemies to be very beautiful, and was often used by Greek artists to fashion purely Greek objects of art, as had already been done at Naukratis under the Saites. But a coarser, sugary glaze, often of darker colour, has also come into use and under the Romans gains the mastery. Only in metal-work, especially in gold and silversmithery, do we still find good work under the Ptolemies, and after the old Ramesside style, which had never died out; for in this domain of art archaism had never found a place, the reason being probably that there was no goldsmith's work of the Old Kingdom known to the Saites which they could imitate. We, with our knowledge derived from archaeological excavation which enables us to survey the whole course of Egyptian art history from beginning to end, know far more of these things than the ancient Egyptians of any one period knew themselves.

The Roman Period: the End.

Of Egyptian art under the Romans one can only speak as a dead thing. The only thing worth looking at is the faience, with its characteristic semi-transparent dark blue glaze, often laid on over yellow to give the effect of green. A fine hard black glaze was also used, as well as an apple green. The sculpture is dry and dull; half-Romanized portraits of classical and Egyptian style are produced, of horrific tastelessness. The temple reliefs are abominable, barbarous, and as bad as any thing that the Nubian imitators of Egyptian art at Napata and Meroe had produced. Egyptian art could not exist any longer by the side of Graeco-Roman art; it was not only provincial, it wa3 definitely barbarous, the childish performance of "natives," which could only cause amusement to the citizen of the modern world empire of Rome. So old Egypt expired, "a driveller and a show." She left a few motives, of religious origin, to the "Coptic" art of the Christian period, which otherwise was Syro-Roman in style.The ancient symbol of "life," , easily became the Christian cross.

Agriculture.

As now, Egypt's staple industry was her agri culture. She early became a granary for the surrounding world, and her corn was no doubt exported to the Aegean or to Syria in ancient days almost as largely as it was to Rome later on. Ancient pictures of the fellahin at work in the fields have much the same appearance as modern representations of the same scenes. The crops were much the same as to-day. Wheat and spelt were used for making bread, of which many ancient specimens have been preserved in the tombs to our own day. There is no possible truth in modern tales, constantly repeated, of ancient mummy-wheat being planted nowadays and producing a crop; the germ cannot live more than a few years, and the grain is always certainly modern. Barley was used for making beer. The vine was cultivated and wine made in Egypt, especially in the Oases and the Mareotic district of the delta ; nowadays the climate is considered too dry and hot for the production of good wine. The date-palm was as im portant as it is now. Bee-keeping was a very ancient industry. The title of the king as king of Upper and Lower Egypt meant "Bee man" (byati) , .Honey was much eaten; cane-sugar of course being unknown. Land was usually held by the farmers from a landlord, either the king, a feudal chief, temple-chapter, local squire (a farmer him self) or in late times a wealthy townsman. The king was the nominal owner of all land, but in practice, even at the height of the royal power, he could not claim to own directly the lands of the priests, and if he dared to confiscate any he gained a very bad reputation thereby.

Animals.

The oldest domestic animals of the Egyptians were asses, oxen, sheep, goats, pigs, dogs, cats, geese and ducks. The pig is not often represented, as it was considered unclean. A peculiar breed of sheep, with long twisted horizontal horns, died out as early as the 18th Dynasty, but its peculiar type continued to be represented in the ram-headed god Khnum (confused with the goat of Mendes) . The ordinary breed with helically-twisted horns was the animal of the god Amon. The dog was domesticated very early, as the hound and the turnspit were differentiated as early as the Middle Kingdom. The cat was probably not so domesticated as it is to-day, but as the animal of the goddess Bastet was held in high honour. The horse was not introduced from the East till the time of the Hyksos about 1700 B.C., with the chariot; the do mestic fowl not till the i8th Dynasty, when its phenomenal powers of laying were regarded with wonder ("the bird that brings forth every day") . Neither horse nor fowl ever were regarded as sacred, or gave heads to Egyptian therianthropic gods, although in very late Roman times a cock-headed Gnostic demon evolved, probably through some confusion with the hawk-headed Horus. The Egyp tian breed of horses became famous in later times, as we see from a well-known biblical reference (1 Kings, x., 28) ; and in the 8th century king Pi`ankhi in an expedition from Nubia extends his clemency to those princes who treated their horses well, and cen sures one for neglecting his. The horse was not ridden till Saite times. The donkey and the pig dispute the honour of giving a head to the god Set. The camel was never used in the Nile valley, being confined to the Arabian desert, and is never represented till the latest period. The baboon and other species of apes can hardly be regarded as domesticated, but were well-known from early days, especially the dog-headed baboon, the animal of Thoth, the god of learning. The elephant was not generally domesticated, or used in war till Ptolemaic days. It was however well known from pre dynastic times, and later was often brought as tribute from Asia, where it still lived in North Mesopotamia and Syria. The lion, also brought from inner Africa and Mesopotamia (where it still ex isted till the middle of the 19th century in the Euphrates marshes) was trained to accompany the king (under the i8th and 19th Dynasties) in war.The tiger, of course, was unknown to the Egyptians, but the hyena, wolf and jackal were indigenous, the two latter animals being held in high religious honour, the jackal being thus placated in very early days in order to persuade him not to ravage the graves of the dead in the desert (see Religion). The giraffe was brought from Kordofan, as tribute from the negroes, with the baboon. The hippopotamus and crocodile were among the com monest denizens of the Nile; the former persisted in the Delta till the beginning of the 19th century, while the latter has only quite recently retired from Upper Egypt and Nubia to the region south of the Second Cataract. Both gave heads to Egyptian deities. Of other non-domesticated animals the ibis is the best known : also sacred to Thoth (see Religion) .

Architecture

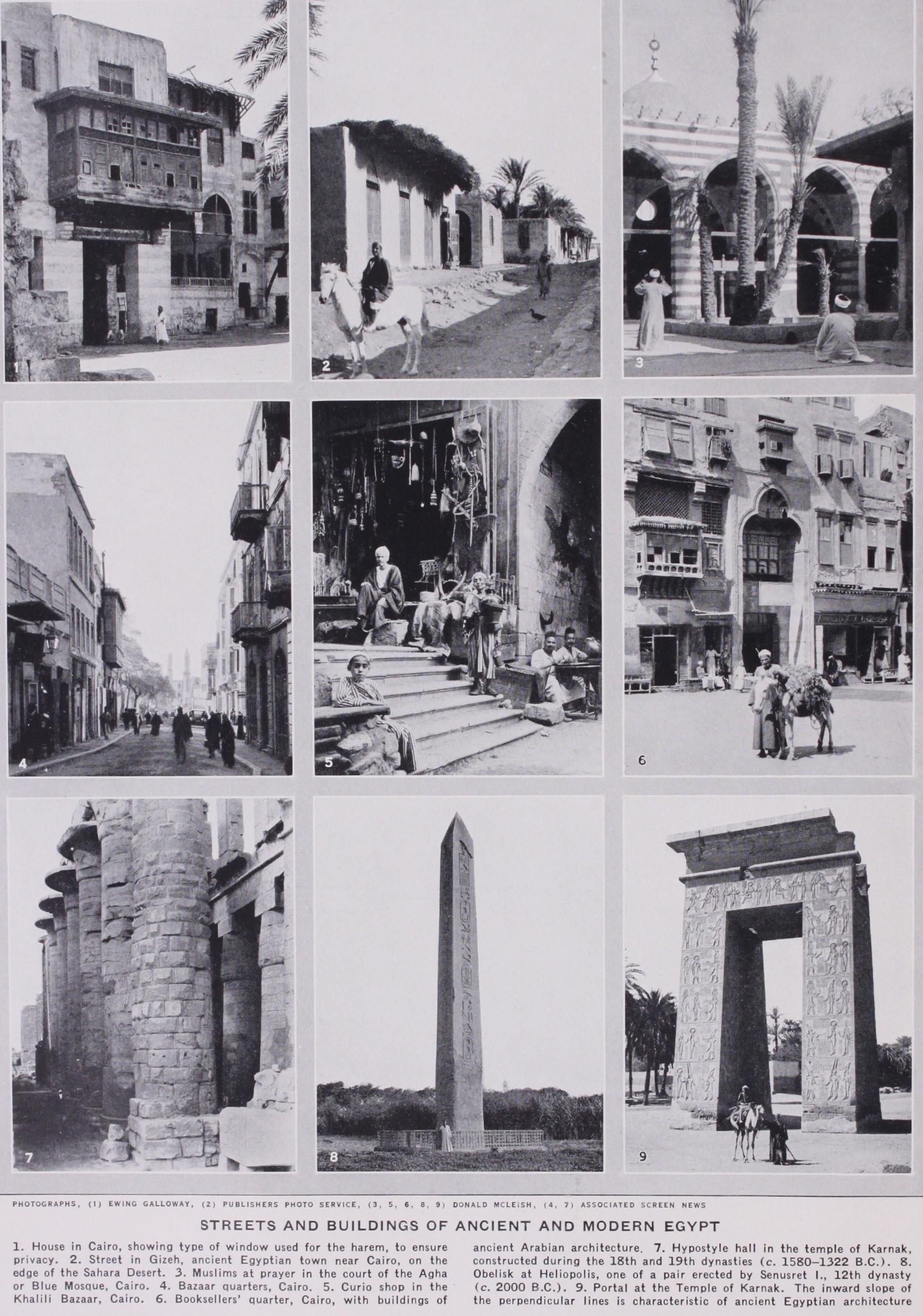

(see also Art).—There is a model in the British museum of a pre-dynastic house, a box of pottery with a lid, in the shape of a long hut with a door with beam-architrave. The well-known Egyptian splay and torus moulding is certainly of pre dynastic origin, being an imitation of the splaying tops of the rows of reeds of which a reed hut was built, bound together by a roll of cord along the length of the roof. Details of stone shrines in later days which are evidently modelled on wooden originals (at Dair al-bahri under 11th Dynasty, where the carved limestone is painted to imitate the grain of wood) show strong and well designed carpenter's work in early building. Although brick may be an Egyptian invention independent of Babylonia, wall-details were either borrowed from Babylonia, or by both Egypt and Babylonia from a common source. The sudden development of stone building under the 3rd and 4th Dynasties has been de scribed, and the stereotyping of temple-details under the 5th. Of Middle Kingdom buildings we have the 11th Dynasty funerary building at Dair al-bahri and that of the 12th at Lisht, besides the pyramids of the kings at Dashur, Lahun and elsewhere. The undecorated walls, built of gigantic stones, of the "Temple of the Sphinx" at Gizeh and the Osireion at Abydos, which have been attributed to this dynasty, are certainly in the case of the Osireion much later, belonging to 19th, while the view that the Gizeh build ing may be of the Pyramid epoch is not disproved. Both are sub terranean buildings built for certain funerary purposes connected with Osiris in the underworld. The temple developed its full mag nificence under the i8th and 19th Dynasties. While the gods were housed in halls of granite and sandstone, the kings continued to live in palaces of mud-brick, decorated however with beautiful wall-paintings; stone being confined to pillar-bases and thresholds, sometimes also doorjambs, architraves and beams being of wood. Large halls were often built of this construction. The systematic excavation of the ruins of Akhetaten, the town of Ikhnaton at Amarna by the Egypt Exploration Society, following the work of the German Orient-Gesellschaft, is teaching us much regarding Egyptian domestic architecture. Streets were broad at Akhetaten, and suitable for chariots abreast, but the town was a new founda tion, and we cannot doubt that the alleys of an old city were as tortuous and noisome as they are to-day. Housebuilding has really altered very little in Egypt or in `Iraq, and the ways of the people are the same as in ancient days; in few countries is the complete continuity of modern civilization with that of four thou sand years ago so evident as in Egypt. Foreign ideas appeared from time to time, sometimes owing to a royal whim, as in the famous case of the outer gate of the temple of Rameses III. at Medinet Habu, which is an imitation in sandstone of a Syrian migdol or fortified tower. In later days the temple-architecture becomes coarse and ugly, until revived and refined to some extent by Saite archaism. The Ptolemaic age has left us at Dendera, Edfu, and elsewhere the only completely roofed and well-pre served temple-buildings we have ; Edfu indeed is practically per fect and gives a magnificent idea of what an older temple was like, for though the Ptolemaic sculptors could only design wall-reliefs childishly, the architects were well able to reproduce the buildings of the past. Even the Roman age at Esneh has left no inconsider able monument. Details of course altered in time, became mis understood, debased or vulgarized, but the main appearance of a temple was the same as it had been under the Old Kingdom— the style was the same. There were no religious buildings in Egypt of clashing styles. The pillar capitals of the lily and papyrus orders established by the time of the 5th Dynasty (the closed lily bud capital dates from the 3rd at Sakkara) continued to the end. The bud-capital was very popular under the i 8th and i 9th Dynas ties, and under the loth became a terrible caricature. The inverted flower, often used for wooden canopy pillars, was used once only in temple-architecture, by Thutmosis III. at Karnak and was not approved. By Ptolemaic and Roman times capitals became very elaborate and rococo. The art of building an Egyptian temple was simple, being merely that of the child who builds with a box of wooden bricks. It is the mass and weight of the "bricks" that are astonishing. There is no doubt that though the Egyptians possessed in early days a primitive kind of crane (probably) and a sort of rocker which could transfer heavy stones from a lower to a high position, much of their building was achieved by sheer man-hauling up mounds of earth. The Egyptian is an adept at throwing-up earth embankments speedily, on account of their necessity in the scheme of irrigation ; and he built his temples by hauling the stones with ropes and levers up an earth-slope to the height demanded. An architrave was placed across two pillars in this simple way, which has been used in modern days for the restoration of Karnak. Such levers, ropes, mallets, etc., are often found in excavations of temples. Implements such as squares, plumb-lines, etc., were used. The mason's square R was a very lucky amulet.

Arms and Armour.—The first copper weapons discovered in Egypt appeared about the middle of the pre-dynastic period in the shape of triangular daggers. Axe-heads of copper, of simple rounded shape, were common under the earlier dynasties. Under the r 2th Dynasty the usual Egyptian hatchet-shape was intro duced, sometimes for weapons of parade with decoration of groups of animals in open-work, sometimes with scenes in inlaid metal work, as in the case of the famous dagger of Queen A'ahhotep in the Cairo museum. Decoration of this kind, showing pictures of fighting and hunting in variously coloured metals, was probably of Aegean origin, introduced into Egypt. The finest known examples are the inlaid daggers from the shaft-graves at Mycenae (c. i600 B.e.). Spearheads, tanged, first appear in the early Middle Kingdom. The pear-shaped stone macehead, com mon as a weapon under the early dynasties, went out of use about the same time. The dagger, often with spiral inlay (also Aegean) on the blade, was hilted with a peculiarly-shaped handle of ivory. Bronze now came into use for the finer weapons. Under the Hyksos the Syrian scimitar or K'hepesli was introduced from Asia, and be came a characteristic Egyptian weapon. The axehead under the 18th Dynasty continued as before, and was still stuck through the haft and secured by leather bands; the invention of the socket, well-known in Babylonia nearly 2,000 years before, not yet having been adopted in Egypt for the axe : socketed spearheads appeared however. Long swords were of foreign make and only used by for eign mercenary troops from South-East Anatolia (Shardina) ; an example is to be seen in the British Museum. A heavy bill, with a peculiar blade weighted by a round ball, which took the place of the old mace, was also probably of foreign origin. The peculiar ivory round-tipped dagger-hilt of the Middle Kingdom and early i8th Dynasty was giver. up in favour of a hilt of foreign type, probably Aegean, made of fine stone such as crystal or chalcedony. The gold and iron daggers from Tutankhamun's tomb have hilts of this type, decorated with gold granulated chevron patterns. Bows and arrows were known from the beginning, but the Egyptian bow was not a very powerful weapon, although it was said that no man could bend the bow of king Amenhotep II. Iron, known for weapon making as early as the Hyksos period (a spear of that time was found in a Nubian grave), came first into gen eral use in the 14th and i3th centuries B.C., and by the time of the Saites was universally used in Egypt as elsewhere, bronze sur viving only for weapons of parade and for arrowheads, just as stone had survived for arrowheads well into the bronze age, the commoner and cheaper material being used at all times for weapons that could not be retrieved. The Egyptian flint arrow head was usually of a peculiar flat-edged, not pointed type, like a front tooth. For hunting plain hard wood points were generally employed. Arrows were carried in quivers, suspended at the side of the chariot. Body-armour was never in great favour in Egypt, no doubt owing to the heat. It does not appear at all till the late New Empire, when helmets, often plumed, of a laminated con struction (probably, again, of Aegean origin) began to be worn occasionally, though they were never common, and armour of slats or scales of metal or bone sewn on to a leather or linen hauberk ; laminated armour, apparently introduced by the Ana tolian mercenaries of the time, like the big broadswords already mentioned. This "linen" armour, sometimes made with crocodile skin, was still used under the Saites, when Greek metal armour was introduced, but was used probably only by princes.

Boats and Shipping.—Oared boats were known in the pre dynastic period, and carried insignia (so-called "totem-poles"), the sacred animals or symbols of tribes (later the names) on poles. A masted and sailed boat occurs on a vase of the middle pre dynastic period in the British museum; the sail is square. Square sailed boats were common under the Old Kingdom and thence forward. Great boats were used in the Mediterranean to fetch wood from Phoenicia (the Lebanon) at least as early as the 3rd Dynasty. Ships had navigated the Red sea as early as the pre dynastic age, and are represented on the handle of the al-'Araq knife, and we find them regularly mentioned as sailing to Punt (Somaliland) at least as early as the s r th Dynasty. A tale of the Middle Kingdom tells us of the strange adventures of a ship wrecked sailor in the Red sea, and voyages to Gebal (Byblos) in Phoenicia were common. Under Hatshepsut (i 8th) we have representations of great sailed and oared galleys going to Punt. Whether Egyptian ships ever got so far as Babylonia or India we do not yet know, but Babylonian vessels seem to have come up the Red sea to the Sinaitic peninsula in search of stone at a very early period. In the Mediterranean, the ubiquity of the Cretan and Phoenician sailors no doubt prevented any great development of Egyptian shipping : under the i 8th Dynasty we see a Phoenician ship depicted unloading at a quayside at Thebes. The anarchy in the Mediterranean after the fall of the Minoan civilization probably put an end to Egyptian maritime enterprise in the North. When an ambassador of the loth Dynasty goes to Phoenicia he sets sail in a Phoenician ship. Under the Saites, however, we see a revival of Egyptian enterprise on the water; very large vessels were built for war service on the Nile, and Egyptian sailors fought well in the service of Persia at Artemision and at Salamis. Egyptian ships were always known by individual names, such as "Appearing in Memphis" (early i8th Dynasty), "The sun-disk lightens," (late 13th Dynasty) "The Ship of Amon," and "The Great Ship of Sais" (26th Dynasty). Sailors and shipmen, espe cially those of the royal barges, are often mentioned on the monuments. Canopic Jars, Coffins, etc. (see Religion.) Ceramics.—Egypt affords us the most striking instance of the development of the potter's art. As in other countries pottery was made even in Neolithic times, for the Nile mud forms a fine plastic clay and sand is of course abundant. With these materials, various kinds of pottery, often extremely well made' and of good form, have been continuously produced for common domestic requirements, but such pottery was never glazed.

The wonderful glazes of the Egyptians were applied to a special preparation which can hardly be called pottery at all, it contained so little clay. Yet as early as the 1st Dynasty the Egyptians had learnt to shape little objects in this tender material and cover them with their wonderful blue glazes. We have there fore to study the development of two independent things : (1) the ordinary pottery of common clay left without glaze; (2) the brilliant glazed faience which appears to be special to Egypt, though it may have been the groundwork for the technique of the slip-faced painted and glazed pottery of the nearer East. We probably possess specimens of the most primitive Neolithic pot tery in that of "Badarian" type recently found by Sir Flinders Petrie at al-Badari in Upper Egypt. The black and red ware of Ballas and Naqada is later. This ware is very hard and com pact and the face is highly burnished. The red colour was pro duced by a wash of fine red clay; the black is an oxide of iron obtained by limiting the access of air in the process of baking, which was done, Prof. Sir Flinders Petrie suggests, by placing the pot's mouth down in the kiln, and leaving the ashes over the part which was to be burnt black. Both red and black colour go right through in every case. Allred and all-black vases are occasionally found, the red with geometrical decorations in white slip colour, and the black with incised decoration. The forms are usually very simple, but at the same time graceful, and the grace of form is more remarkable when it is remembered that none of this early pottery was made on the wheel.

A very similar red and black ware, usually of thinner and harder make, and often with a brighter surface, was introduced into Egypt at a later date (12th Dynasty), probably by Nubian immigrants who were descended from relatives of the Neolithic Egyptians. From their characteristic graves these people are called the Pan-Grave people, and their pottery is known by the same name.

Later in date than the early red and black wares, the second characteristic type of primeval Egyptian pottery is a ware of buff colour with surface decorations in red. These decorations are varied in character, including ships, birds and human figures; wavy lines and geometrical designs commonly occur (see Art). They are the most ancient handiwork of the Egyptian painter, and mark the first stage in the development of pictorial art on the banks of the Nile. Some other types of pottery, in colour chiefly buff or brown, were also in use at this period; the most noticeable form is a cylindrical vase with a wavy or rope band round it just below the lip, which developed out of a necked vase with a wavy handle on either side. This cylindrical type, which is probably of Syrian origin, outlived the red and black and the red and buff decorated styles (which are purely pre-dynastic) and continued in use in the early dynastic period, well into the cop per age. The other unglazed pottery of the first three dynasties is not very remarkable for beauty of form or colour, and is indeed of the roughest description, but under the 4th Dynasty we find beautiful wheel-made bowls, vases and vase-stands of a fine red polished ware. Under the 12th Dynasty, and during the Middle Kingdom generally, a coarser unpolished red ware was in use. The forms of this period are very characteristic ; the vases are usually footless and have a peculiar globular or drop like shape—some small ones seem almost spherical.

The art of making a pottery consisting of a siliceous sandy body coated with vitreous copper glaze seems to have been known unexpectedly early, possibly even as early as the period imme diately preceding the 1st Dynasty (4000 B.c.). The oldest Egyp tian glazed ware is found usually in the shape of beads, plaques, etc.—rarely in the form of pottery vessels. We find tiles made of it at Sakkara under the 3rd Dynasty, and under the 6th and 12th Dynasties pottery made of this characteristic Egyptian faience came into general use and continued in use down to the days of the Romans, and is the ancestor of the glazed ware of the Arabs and their modern successors. The colour is usually a light blue, which may turn either white or green ; but beads of the grey-black manganese colour are found, and on the light blue vases of King Aha (who is probably one of the historical originals of the legendary "Mena" or Menes) in the Brit. mus. (No. 38,010) we have the king's name traced in the manganese glaze on (or rather in) the blue-white glaze of the vase itself, for the second glaze is inlaid. This style of decoration in manganese black or purple on copper-blue continued till the end of the "New Em pire" shortly before the 26th (Saite) Dynasty. It was not usual actually to inlay the decoration before the time of the 18th Dynasty. The light blue glaze was used under the 12th Dynasty (Brit. mus., No. 36,346), but was then displaced by a new tint, a brilliant turquoise blue on which the black decoration shows up in sharper contrast than before. This blue, and a somewhat duller greyer or greener tint was used at the time for small figures, beads and vases, as well as for the glaze of scarabs, which, however, were usually of steaschist or steatite—not faience. The character istically Egyptian technique of glazed stone begins about this period, and not only steatite or schist was employed (on account of its softness) but a remarkably brilliant effect was obtained by glazing hard shining white quartzite with the wonderfully deli cate 12th Dynasty blue. A fragment of a statuette plinth of this beautiful material was obtained during the excavation of the 11th Dynasty temple at Dair al-Bahri in 1904 (Brit. mus., No. 40,948). Vessels of diorite and other hard stones are also found coated with the blue glaze. A good specimen of the finest 12th Dynasty blue-glazed faience is the small vase of King Senwosret I. (2000 B.c.) in the Cairo museum (No. 3,666). The blue-glazed hippo potami of this period, with the reeds and water-plants in purplish black upon their bodies to indicate their habitat, are well known (P1. VII., figs. I and 2) . Fine specimens of these were in the collection of the Rev. Wm. MacGregor at Tamworth.