Isolation of the Electron

ISOLATION OF THE ELECTRON Definition of Positive and Negative Electric Charges.— It will probably be agreed that the most unambiguous single bit of evidence for the atomicity of electricity is found in the "oil drop experiment," which puts the proof both of the unitary nature of electricity and of the electrical constitution of matter into such simple and unquestionable form that one needs, as a background, little more than a bare definition of electricity in order to see that both results follow from the experimental facts.

What, then, is electricity? Of its ultimate nature we know very little, precisely as we know very little of the ultimate nature of matter, or of the ether, or of mind, or, indeed, of the ultimate nature of anything. Science does not deal with ultimates, but rather with relations between observed or observable phenomena. Our ignorance of ultimates, however, does not prevent us from setting up a sharp, quantitative definition of an electric charge which anyone can understand. Everyone knows that, if he combs his hair with an ebonite comb, both the comb and his hairs acquire strange new properties of such sort that the hairs violently repel one another and are equally violently attracted by the comb. The forces thus called into play are enormously stronger than the gravitational forces acting upon the hairs. Merely for the sake of having a name by which we can describe and remember them we call them electrical forces, and the bodies that exhibit them are by definition said to possess charges of electricity. Again, since a glass rod that has been rubbed with silk violently repels hairs or other light electrified bodies that are violently attracted by ebonite that has been passed through hair or been "rubbed with cat's fur," we arbitrarily say that any electrified body that is repelled by a glass-rod-rubbed-with-silk possesses a charge of positive electricity, and any body that is repelled by an ebonite rod-rubbed-with-cat's-fur possesses a charge of negative electric ity. These are then altogether unambiguous and easily intelligible definitions of positive and negative electricity.

Further, we quite naturally measure

the amount of electricity on a given body by the amount of the force exerted upon it at a given distance by some glass rod or other body which has been rubbed or treated in some standard way. Quite specifically, we define unit electric charge as that charge which, placed upon a minute spherical pithball, will repel with a force of one dyne (about a milligram weight) another similar pith ball, charged in exactly the same way and placed one centimetre away from it. This is the definition of the so-called absolute electrostatic unit of electricity spoken of in the preceding section.

Criterion for Atomicity.

If, now, we wish to put to nature the exceedingly important and very fundamental question, is electricity something that exists in discrete elements or particles, as Franklin imagined it to be, and, if so, are these particles all alike—i.e., is electricity atomic in structure?—it is quite obvious from the foregoing definitions that the simplest and most direct way possible of proceeding in the attempt to get the answer is to take the very smallest obtainable body which can be made to acquire an electrical charge, to measure the electrical force exerted upon it at a given distance by some standard body of invariable charge, then to change the charge on this very small body by the smallest possible amounts, and finally to see whether the forces exerted upon it by the standard body in the course of these changes show any unitary properties, i.e., whether they increase by unit steps or do not so increase. If they do so increase, then the charges here dealt with will have been definitely shown to be multiples of a unit charge. If they do not so increase, we shall not yet be able to deny the atomic or unitary structure of elec tricity, but we shall be certain that, if it has a structure at all, it must be a much finer grained structure than corresponds with the minute changes of charge which we have in these experiments been able to use.

Oil-drop Experiment.

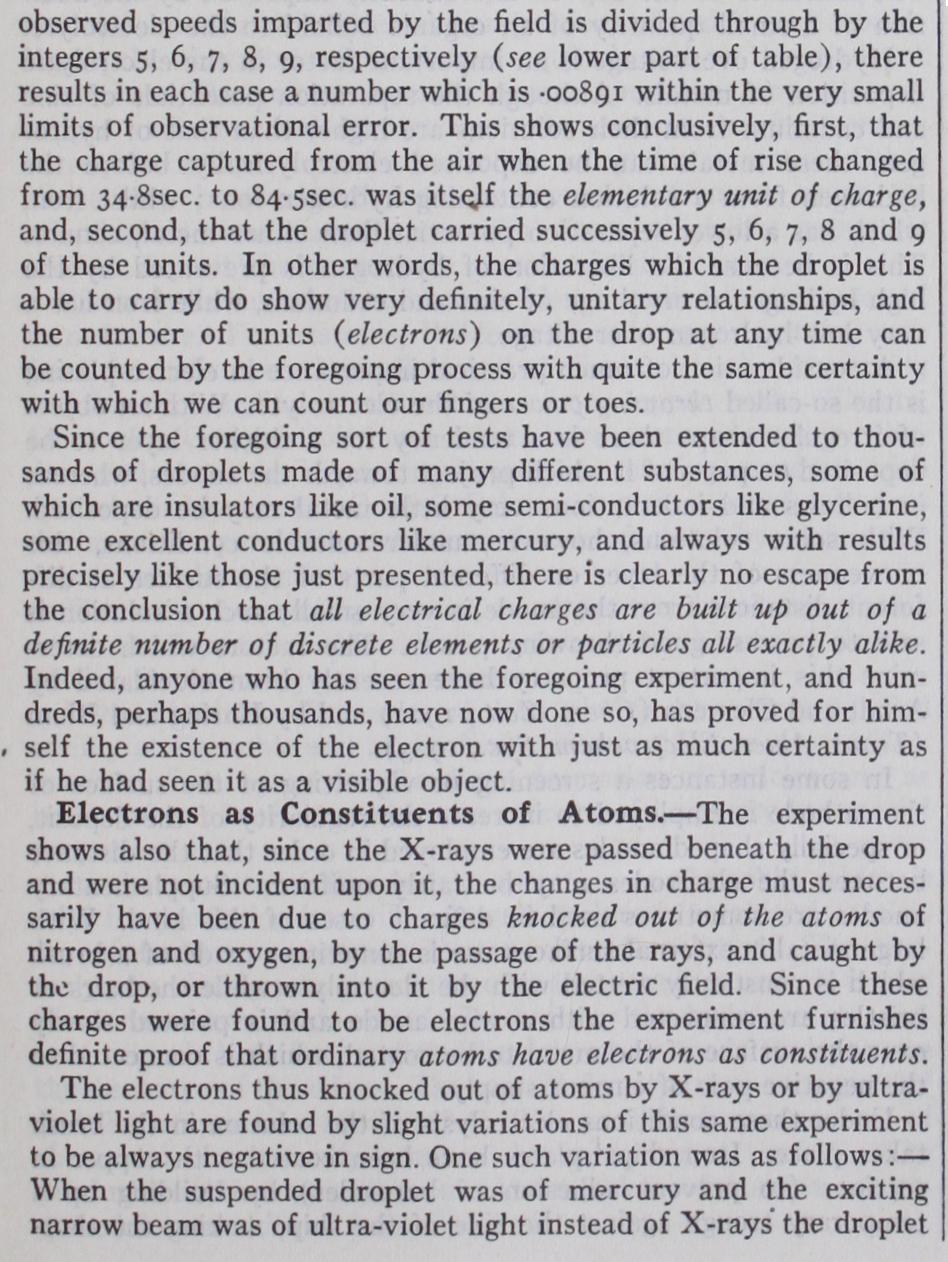

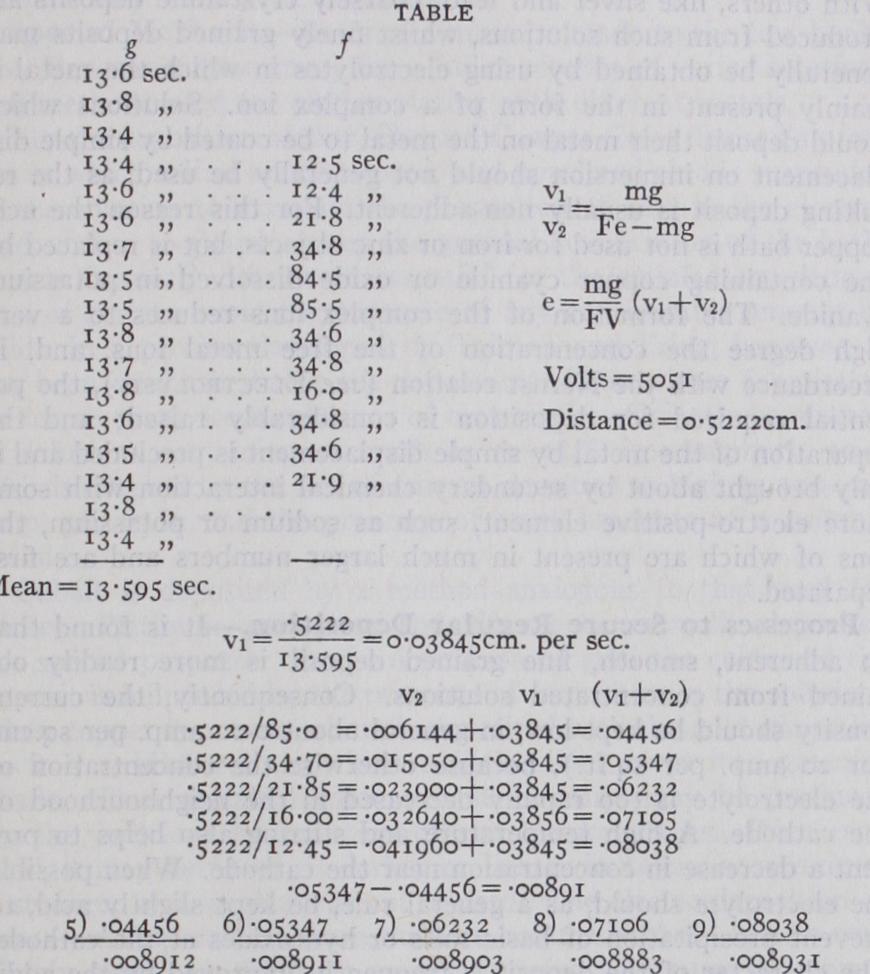

Experiments of this kind were first undertaken in the year 1909. The very minute bodies, the changes in charge of which were to be observed, were the minute droplets of oil in an oil-spray such as is formed by an ordinary toilet atomizer. These were chosen, first, because it was necessary to obtain minute bodies which would not evaporate (modern clock and watch oils represent a hundred years of effort in the develop ment of non-evaporable and non-gumming, lubricants) and, sec ondly, because these droplets of oil-spray were as minute spherical bodies as anyone could ever hope to obtain and still have them visible ; so that the changes in the force exerted upon them by a constant electrical field could be accurately measured. The constant electrical field was obtained by attaching the terminals of a ten-thousand volt battery to the circular brass plates (fig. i) held about i6mm. apart by three insulating posts. This arrangement produced an altogether uniform and constant electri cal field between the plates, and a charged oil drop in that field would have imparted to it, by the field, a speed which, according to the well-known laws of motion of a small body through a resisting medium, would be strictly proportional to the charge upon the drop. The actual procedure was first to disconnect the battery from the brass plates, short-circuiting them in so doing so that no field existed between them, then to send a puff of air through the atomizer, thus producing a cloud of oil droplets above the minute pin-hole in the middle of plate. One or more of these droplets would then find its way through this pin-hole into the space between the plates. This droplet was rendered visible by passing a powerful beam of light from an arc between the plates and looking through a short-focus telescope at the droplet in a direction nearly at right angles to the beam. In this beam the droplet appeared like a bright star floating slowly downward toward the lower brass plate. Bef ore it struck the plate the switch was thrown so as to create the electric field in the space between the plates. The droplet, if properly charged by the frictional process involved in blowing the spray, would then begin to rise against gravity, because of the pull of the field on its charge. Just before it could strike the upper plate, the field would be thrown off by opening the switch, and the droplet would then begin to fall again at exactly its former rate. Its successive times of fall under gravity and of subsequent rise under the action of the field were then taken. The table gives a typical set of read ings, the first column headed g giving the successive numbers of seconds required for the droplet to fall, with no field on, the dis tance between two fiducial marks in the eyepiece which corre sponded to an actual distance of fall of exactly . 5 2 2 2 cm. The sec ond column headed f, gives successive numbers of seconds re quired for the droplet to rise under the action of the field upon its charge. Between the second and third trips up, the charge on the droplet was changed by passing underneath it a beam of X-rays from the X-ray bulb I, and it is sufficient, for the present, to know that this procedure does change the charge, leaving to a later time the discussion of why it changes it. Similarly, a change in charge was brought about between the third and fourth trips up, the fourth and fifth, the sixth and seventh, the ninth and tenth, and the eleventh and twelfth.

Proof of Atomicity.

Now, the striking result which appears at once from a glance at column f is that only a few definite times of rise seem to be possible, and these recur continually, thus indicating that only certain definite charges can be placed upon the drop. These charges are proportional to the speeds im parted by the field, and, since the action of the field is first to neutralize the downward speed, imparted by gravity, and then to impart an upward speed in addition, the total speed imparted by the field is actually obtained by adding the downward speed due to gravity, and the upward speed in the field. The results of such addition are shown in the middle portion of the table under the heading The difference between the first two of these, corresponding to the two times of rise 34.7sec. and 85.osec., respectively, is which therefore repre sents, in terms of a speed, the charge caught from the air between the fourth and fifth trips up. When the whole succession of did not change its charge when the beam passed underneath it (ultra-violet light has not a sufficiently short wave-length to detach electrons from the molecules of nitrogen or oxygen) but only when the light shone directly on the droplet itself ; and then the sudden changes in its motions were always such as to show that it was invariably a negative, never a positive, electron that was detached from the mercury atoms of the drop by the inci dence of ultra-violet light. These and slightly different experiments with X-rays show that it is only the negative, never the positive, electronic constituents of atoms that can be detached by external agencies such as molecular bombardment, incident aether waves, or temperature. As a matter of fact we now know that all the positive electrons in an atom are concentrated in its very minute nucleus.

Further in the course of the oil-drop experiment it was found possible to change the charge on the droplet, and to obtain an oil or a mercury drop altogether electrically neutral, which therefore falls under gravity with exactly the same speed when the electrical field is on as when it is off—a very important fact from which it follows that the negative constituents of the mer cury, or other atoms, have as partners in the drop exactly as many unit positive charges as they have negative charges. In other words, we have here evidence that all atoms of which we have any knowledge have in them a certain definite number of negative electrons and exactly the same number of positive elec trons, else they could not be obtained in the neutral condition. (This number can now be counted with certainty by a number of methods, the simplest being the method of Moseley.) The discovery of the unitary or electronic structure of elec tricity means, of course, that all electrical phenomena must hence forth be interpreted in terms of the positions and movements of positive and negative electrons.

Absolute Value of the Electron.

The measurement of the absolute value of the electron was made by means of the oil-drop method, and involved a very large number of precise measure ments of the foregoing sort upon a very large number of oil droplets of widely varying sizes, floating, or falling, in many different sorts of gases, at many different pressures varying from one and a half millimetres of mercury up to 76o millimetres. By such a series of measurements the results were made independent of the gas pressures, and of the individual properties both of the droplets and of the media in which they floated. The details of these measurements will be here omitted, and only the final result stated; viz., that all the different series of measurements on different drop-substances and in different media always pointed infallibly, as shown by the convergence point of fig. 2, to the value 61 •o85X io which corresponds to the absolute value of the electron e=4.774X10-1° absolute electrostatic units, or I,592XIO 2° electromagnetic units. This is correct to about one part in a thousand.The electron is one of the most important of all physical stants; for the absolute tudes of practically all molecular and atomic quantities are mined as soon as it is accurately known, but they are able without it. Thus, for ple, the so-called Faraday stant, the amount of electricity required to deposit from a tion one gramme molecule of a univalent substance, like hydrogen or silver, is found to be 96,494. coulombs, or absolute electromagnetic units; but this is ously equal to Ne where N is the number of molecules in a gramme-molecule, and e is the value of the electron in magnetic units. Hence, as soon as e had been accurately mined N could be at once computed with precisely the same degree of precision obtained in the measurement of e. N is thus found to be This number of molecules in a molecule is usually called the Avogadro number. From it we determine at once the number of molecules in a cubic centimetre of any gas, or, indeed, the exact number of molecules in a given weight of any substance whatever of known molecular weight, so that our knowledge of practically all absolute atomic and molec ular magnitudes comes from the evaluation of e. The same is true to a somewhat lesser extent of atomic dimensions and of radiation constants. Thus, e takes its place as a constant of outstanding practical and theoretical importance. All electrical currents are caused by the slow travel of a well-nigh infinite number of these electrons along the wire which carries the current. All light or other short wave-length radiations are caused by changes in posi tions of electrons within atoms. All atoms are built up out of definite numbers of positive and negative electrons. All chemical forces are due to the attractions of positive for negative electrons. All elastic forces are due to the attractions and repulsions of electrons. In a word, matter itself is electrical in origin.