Lmml

LMM'L', and must therefore be a submultiple of the length of the circuit. Lecher showed that if instead of using a single wire LM to form the bridge, he used two parallel wires PQ, LM, placed close together, the currents in the further circuit were hardly appreciably diminished when the main wires were cut between PL and QM. Blondlot used a modification of this apparatus better suited for the production of short waves. In his form (fig. 9) the exciter consists of two semicircular arms connected with the terminals of an induction coil, and the long wires, instead of being connected with the small plates, form a circuit round the exciter.

As an example of the use of Lecher's arrangement, we may quote Drude's application of the method to find the specific in duction capacity of dielectrics under electric oscillations of vary ing frequency. In this application the ends of the wire are connected to the plates of a condenser, the space between whose plates can be filled with the liquid whose specific inductive capacity is required, and the bridge is moved until the detector at the end of the circuit gives the maximum deflection. Then if X is the wave length of the waves, X is the wave length of one of the free vibrations of the system HLM J ; hence if C is the capacity of the condenser at the end in electrostatic measure we have where l is the distance of the condenser from the bridge and C' is the capacity of unit length of the wire. In the condenser part of the lines of force will pass through air and part through the dielectric; hence C will be of the form where K is the specific inductive capacity of the dielectric. Hence if l is the distance of maximum deflection when the dielectric is replaced by air, l' when filled with a dielectric whose specific inductive capacity is known to be K', and t" the distance when filled with the dielectric whose specific inductive capacity is required, we easily see that— an equation by means of which K can be determined. It was in this way that Drude investigated the specific inductive capacity with varying frequency, and found a falling off in the specific inductive capacity with increase of frequency when the dielectrics contained the radicle OH. In another method used by him the wires were led through long tanks filled with the liquid whose specific inductive capacity was required ; the velocity of propaga tion of the electric waves along the wires in the tank being the same as the velocity of propagation of an electromagnetic disturb ance through the liquid filling the tank, if we find the wave length of the waves along the wires in the tank, due to a vibration of a given frequency, and compare this with the wave lengths corre sponding to the same frequency when the wires are surrounded by air, we obtain the velocity of propagation of electromagnetic disturbance through the fluid, and hence the specific inductive capacity of the fluid.

Velocity of Propagation of Electromagnetic Effects through Air.—The experiments of Sarasin and De la Rive already described have shown that, as theory requires, the velocity of propagation of electric effects through air is the same as along wires. The same result had been arrived at by J. J. Thomson, although from the method he used greater differences between the velocities might have escaped detection than was possible by Sarasin and De la Rive's method. The velocity of waves along wires has been directly determined by Blondlot by two different methods. In the first the detector consisted of two parallel plates about 6 cm. in diameter placed a fraction of a millimetre apart, and forming a condenser whose capacity C was determined in electromagnetic measure by Maxwell's method. The plates were connected by a rectangular circuit whose self-induction L was calculated from the dimensions of the rectangle and the size of the wire. The time of vibration T is equal to 27r V (LC). (The wave length corresponding to this time is long compared with the length of the circuit, so that the use of this formula is legitimate.) This detector is placed between two parallel wires, and the waves produced by the exciter are reflected from a movable bridge. When this bridge is placed just beyond the detector vigorous sparks are observed, but as the bridge is pushed away a place is reached where the sparks disappear; this place is distance 2/X from the detector, when X is the wave length of the vibration given out by the detector. The sparks again disappear when the distance of the bridge from the detector is 3X/4. Thus by measur ing the distance between. two consecutive positions of the bridge at which the sparks disappear X can be determined, and v, the velocity of propagation, is equal to X/T. As the means of a num ber of experiments Blondlot found v to be 3•02 X cm./sec., which,within the errors of experiment, is equal to 3 X cm./sec., the velocity of light. A second method used by Blondlot, and one which does not involve the calculation of the period, is as follows: —A and A' (fig. Io) are two equal Leyden jars coated inside and outside with tin-foil. The outer coatings form two separated rings a, a', and the inner coatings are connected with the poles of the induction coil by means of the metal pieces b, b'. The sharply pointed conductors p and p', the points of which are about 2 mm. apart, are connected with the rings of the tin-foil a and a', and two long copper wires pca, Io29 cm. long, connect these points with the other rings al, The rings aa', chat', are connected by wet strings so as to charge up the jars. When a spark passes between b and b', a spark at once passes between pp', and this is followed by another spark when the waves travelling by the paths cp, reach p and p'. The time between the passage of these sparks, which is the time taken by the waves to travel 1029 cm., was observed by means of a rotating mirror, and the velocity measured in 15 experiments varied between 2.92 X and 3.03 X cm/sec., thus agreeing well with that deduced by the preceding method. Other deter minations of the velocity of electromagnetic propagation have been made by Lodge and Glazebrook, and by Saunders.

On Maxwell's electromagnetic theory the velocity of propaga tion of electromagnetic disturbances should equal the velocity of light, and also the ratio of the electromagnetic unit of electricity to the electrostatic unit. A large number of determinations of this ratio have been made :— The mean of these determinations is 3•ooI X cm./sec., while the mean of the last five determinations of the velocity of light in air is given by Himstedt as 3•002 X cm./sec. From these experiments we conclude that the velocity of propagation of an electromagnetic disturbance is equal to the velocity of light, and to the velocity required by Maxwell's theory.

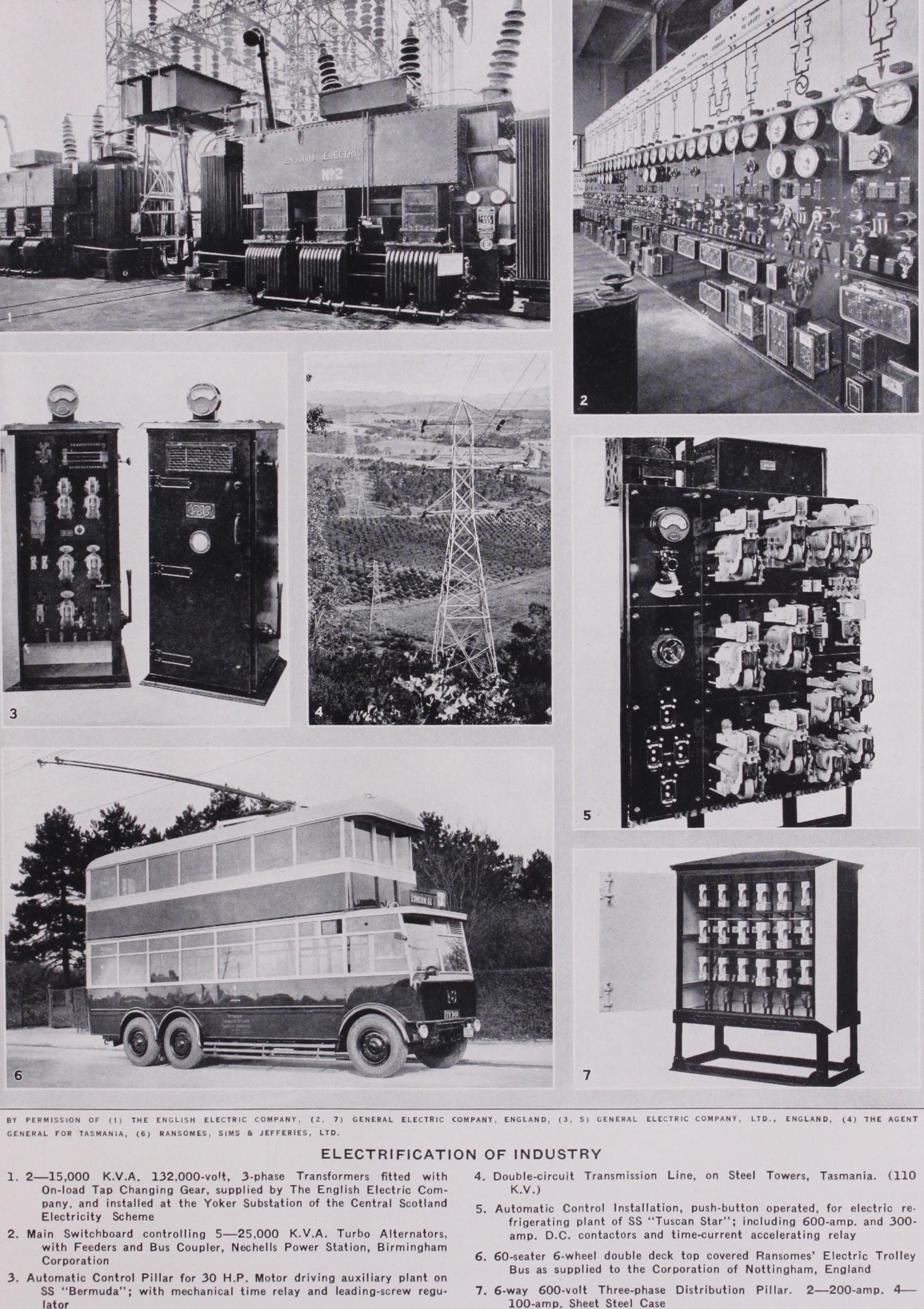

In experimenting with electromagnetic waves it is in general more difficult to measure the period of the oscillations than their wave length. Rutherford used a method by which the period of the vibration can easily be determined; it is based upon the theory of the distribution of alternating currents in two circuits ACB, ADB in parallel. If A and B are respectively the maximum cur rents in the circuits ACB, ADB, then when R and S are the resistances, L and N the coefficients of self-induction of the circuits ACB, ADB respectively, M the coefficient of mutual induction between the circuits, and p the frequency of the currents. Rutherford detectors were placed in the two circuits, and the circuits adjusted until they showed that A = B ; when this is the case If we make one of the circuits, ADB, consist of a short length of a high liquid resistance, so that S is large and N small, and the other circuit ACB of a low metallic resistance bent to have considerable self-induction, the preceding equation becomes ap proximately p = S/L, so that when S and L are known p is readily determined. (J. J. TH.) ELECTRIFICATION OF INDUSTRY. There are three considerations involved in the application of the electric drive in industry, all of which need careful attention if the work is to be fully successful. These are (I) the motor; (2) the control gear; (3) the close co-ordination of these two components with the apparatus to be driven. Progress has been made during recent years particularly as a result of the great developments in auto matic and heavy duty control gear, and in the co-ordination of all the components into a harmonious unit. The author, there fore, proposes to begin by considering briefly the chief types of motor employed for industrial drive, and the most recent forms of control gear by which their utility has been extended. The electrification of specific industries and equipment will then be considered.