Miscellaneous Electrification

MISCELLANEOUS ELECTRIFICATION Other plant equipment, the electrification of which deserves brief notice includes the following : lifting magnets, large valves, pumps, compressors, swing bridges.

Lifting Magnets.

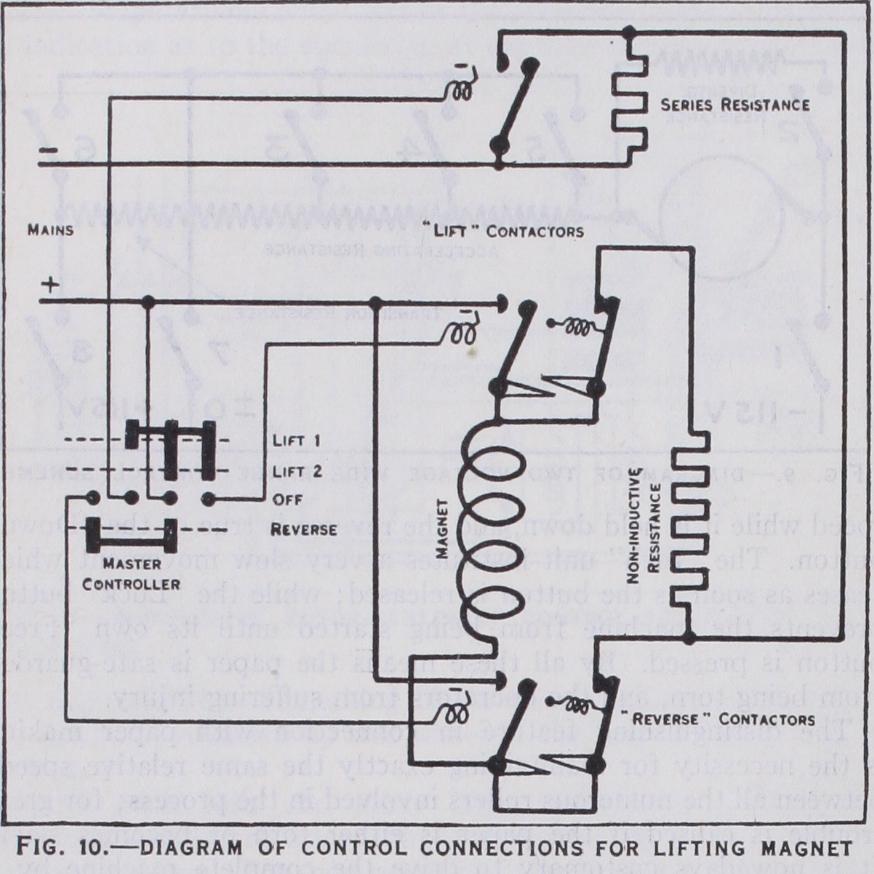

The control of a lifting magnet must make provision both for the potential kick that may occur when break ing circuit, and also for the residual magnetism remaining when the exciting current is switched off, which might be sufficient to retain the load. The former is dealt with by connecting a non inductive "discharge" resistance across the coil just before the supply is cut off; and the latter by means of a momentary re versal of the magnetizing current. A scheme for effecting these steps, and giving two strengths of lifting excitation, is shown in fig. 1o. Auxiliary knock-off contactors are used, operated by a drum controller.

Large Valves.

It is becoming the custom to open and close large steam and water valves electrically, to save the delay, danger and discomfort that are involved in manual operation. The motors range from about 1 to 8 h.p., and are series wound for D.C. and squirrel-cage for A.C. The greatest power is re quired for unseating the valve, which may be jammed or stuck in place, and the starting torque of the motor is frequently assisted by the provision of "lost motion" to impart a hammer blow. After the valve has begun opening, a series resistance is cut into the D.C. armature circuit to prevent racing. A precaution necessary during the closing operation is to stop the motor in time to pre vent jamming. This is accomplished by a limit switch and the end is often assisted by a slipping clutch. Both manual control by means of drum controllers, and automatic control by means of push-button contactor equipment are employed.

Pumping.

The driving of pumps, both centrifugal and re ciprocating, is carried out best by D.C. compound or A.C. squirrel cage or synchronous motors. It may be made automatic by means of contactor gear, operated by float or pressure relays, and forms an economical load, as it may easily be restricted to off-peak hours. The simplest starting schemes, such as the star delta, stator resistance, or even direct switching, are in order for A.C. equipment, the latter being obtained by the use of "across-the-line" type of squirrel-cage and synchronous motors. It is only when a long water column has to be accelerated that special care is needed for bringing about a gradual start.

Fans and Air-compressors.

Ventilation is chiefly of im portance in connection with mining, for which ventilating prac tice is tending more and more in the direction of absolutely continuous running, even during holidays. Conditions thus favour the use of synchronous motors, which can be over-excited to enable them to correct the power factor of the electrical installation gen erally. Since fan duty involves the development of the greatest starting torque just when the rotor is to be pulled into synchro nism, an ordinary self-starting synchronous motor is not in order unless a friction clutch is fitted. The latter is not needed with the synchronous induction motor, which starts as a slip-ring machine and has its rotor excited with D.C. when up to speed. It is customary to employ gearing or belting between motor and fan, which can provide for a gradual increase in capacity as the mine develops by means of a change of gear ratio.For air-compressors, which may be started at light load, the simpler self-starting synchronous motor is well adapted. An ap propriate starting scheme would be one that used an auto-trans former which would reduce the initial voltage. The star point switch is opened during starting and also just before closing the full-voltage switch.

Swing Bridges.

The operation of swing and lift bridges is effected by series D.C. or slip-ring induction motors. The con trol gear need not be automatic, but must be absolutely certain in its action, and must be capable of moving the very heavy masses involved without any possibility of jerking or jolting. A reliable system of interlocks, brakes and signal lamps is used to prevent all chance of mistakes.Motors are employed for moving the span, for locking it, and for opening and closing the gates. Locking motors may be of the squirrel-cage type with high resistance rotors, and need only have a 15 min. rating. The main brakes are usually of the shunt-wound solenoid friction pattern, mounted directly on the motor shafts, and emergency brakes are also installed. The limit switches for effecting slow speed preparatory to seating are important com ponents.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-W. Wilson, Electric Control Gear and Industrial Bibliography.-W. Wilson, Electric Control Gear and Industrial Electrification (1927) ; H. D. James, Controllers for Electric Motors (Second Edition, 1927) ; W. Wilson, Some Notes on the Design of Liquid Rheostats (journal I.E.E., Vol. 6o, p.1q6, I(22) ; D. B. Rush more, Fields of Motor Application (Journal A.I.E.E., Vol. 34, 1915) ; Lozier, The Operation of Machine Shops by individual Electric Motors (Journal A.I.E.E., Vol. 20, p.115, 1902) ; McLain, Eastwood, and Schnabel, three papers on Crane Electrification (Journal A.I.E.E. Vol. 1922) ; L. A. Umanski, Recent Developments in Electric Drive for Rolling Mills (Journal A.I.E.E., Sept. 1927, p.885) ; W. T. Berkshire, Synchronous Motors for Driving Steel Rolling Mills (Journal A.I.E.E., Feb. 1928, p.136) ; Staege, Rogers, and Norris, three papers on Electrification of Paper-Making Machines (Journal A.I.E.E., Vol. 45, 1926) ; Sub-Committee, Application of Electric Power in the Rubber Industry (Journal A.I.E.E., Vol. 4o p.r. 1921) ; W. E. North, Application of Electricity in Cement Mills (Journal A.I.E.E., Sept. 1927, p.881). (W. WIL.) The electrification of America has progressed very rapidly. In 1900 (U.S. Census of Manufactures) there was 11,800,000 h.p. installed in the manufacturing enterprises of which but 4% was electrified. By 1925, the total had reached 35,800,000 horse-power. The American workman in 190o utilized 2.13 h.p. of which but h.p. was electrical. In 1925, he used 4.27 h.p. of which 3.12 h.p. was electrical. Thus, it is apparent that 31 times as much electrical horse-power was used by each American workman in 1925 as was used in 1900. The economic results produced have justified this progress. The American wage-earner in 1925 pro duced products valued at $7,500, or nearly three times what he produced in 1900. From 1919, through 1925 there was a 26% increase in the quantity output of American factories, despite the fact that the average number of industrial workers decreased There has been a very distinct trend by American industry toward the purchase from electric service companies of its power requirements. There has been marked and continued advance in the field of design and application of electrically-actuated ap paratus to the many forms of machinery used in the productive industries.

During the past few years, the "across-the-line" or "line-start" motor has been developed and has received wide application. In duction motors of this type in sizes up to about 5o h.p. may be connected directly to line voltage through a simple magnetically operated switch without exceeding N.E.L.A; specifications for starting current. The use of this motor has greatly simplified the control gear required. Synchronous motors of this type have also been developed and permit the use of simple control for heavy starting duty.

There is a decided increase in the application of high-speed motors. Squirrel cage motors operating at speeds up to 32,400 r.p.m. have been applied to regular production equipment in the ball-bearing industry through the use of frequency changers equipped with S4o cycle generators. In the woodworking industry 120 and 18o cycle motors are being used. The large majority of electrified power consuming equipment in industry is operated by A.C. motors. The predominant use of A.C. has resulted from the simplicity and robustness of the squirrel cage motor and its suitability for constant-speed applications. D.C. motors are used where the advantages of variable speed justify the increased cost of operation. The advance in A.C. motor design, however, has placed at the disposal of industry types so satisfactory that all but very special applications may be served with A.C. motors. Large factories usually utilize both types of current. Equip ment operated at constant speeds are equipped with A.C. motors and D.C. motors are used where variable speed is required. The tendency to equip main roll drives in iron and steel mills with electric drive was continued. These installations utilize mainly D.C. motors of slow speed driven from individual fly-wheel type motor-generators. Some progress has been made in the use of synchronous motors for main roll drives. D.C. mill-type motors have been placed on the market by one American manufacturer. In the rubber industry a synchronous motor having a sufficiently high starting torque to start heavy loads is now available for driving grinding mills, rolls and mixers. This motor operates as an induction motor when it drops out of synchronism and then automatically drops back into step.

A comparatively recent and valuable development has been the application of electric motor drive in the petroleum industry for driving wells in the fields and large pumps in main line pump ing stations. Electrically driven drilling rigs have replaced with complete satisfaction and economy drilling equipment driven by steam and internal-combustion engines. Improvements in the design of mine-type locomotives have resulted in a continuation of the trend toward complete electrification in this industry. De pression in the industry has retarded the electrification programme but in spite of this each year sees more steam-actuated equipment replaced by electric drives. Perhaps the most fertile field for fur ther electrification of our industrial establishments lies in the ap plication of electricity to heating processes. Considerable progress has already been made in this direction. There is every reason to believe that some day the horse-power rating of electric heating and melting equipment in American industry will exceed the total horse-power in motors.

The brass industry for several years has made use of large in duction and arc type furnaces for melting copper alloys in the comparatively few large wrought-brass mills. The development of small units (250 and i,000 lb. capacity), practically all of which are of the single-phase type, have made possible electric melting in the smaller cast-brass establishments. Up to the year 1926 less than 15% of the brass melted in America was melted in electric furnaces. In the steel industry, the three-phase arc furnace pro duces such a high quality of product that "electric steel" has now become virtually a trade-mark. A few installations of this type of furnace have been made for the melting of cast iron and it is expected that this will find larger application. A high-frequency or coreless-type induction furnace has been developed for the melting of high-grade alloy steels. Each of these units consists of a motor-generator set with a single-phase high frequency gen erator and high-frequency capacitor units. The advantages of the electric furnace in producing very high temperatures, in allowing exact temperature adjustment and in providing the possibility of controlling the conditions of operation has established it in the large commercial field where these refinements are necessary. Some of the products in this field are artificial graphite, silicon carbide, artificial emery, metallic silicon, fused quartz, fused silica, fused silico-glass, bisulphide of carbon, zinc, phosphorus, calcium carbide, ferroalloys and other alloys, and steel. Experi mentally the electric furnace has been used to produce modifica tions of carbon, many metals and a great variety of other products.

When steel is made into forging, cold rolled into sheets and strips or drawn into wire, the working of the metal imparts a cer tain amount of hardness which must be removed by annealing, before subjecting the material to subsequent operations. Thus forgings must be softened for machining and sheets must be put in suitable condition for drawing and forming operations. Wire is annealed after each draw to reduce wear of dies and increase ductility of the metal. There is then a final anneal or heat treat ment to make the wire suitable for commercial use. Until about 1922 commercial annealing was carried on in fuel-fired furnaces using coal, coke, oil or gas, and these methods are still in quite general use. The tendency at present, where maximum quality and uniformity of product are desired, is to give consideration to the electric furnace for these operations. The actual cost of the electric energy used is, in many instances, higher than the bare cost of fuel would be, but this is frequently justified by the re sults secured. A properly designed electric furnace operates with a very uniform distribution of heat and at no time is the tempera ture of the heat source much above the annealing temperature. This means that the metal is heated through to just the right de gree and will have the uniform grain structure which character izes a perfect anneal. The furnace temperature is controlled auto matically and is maintained more closely and accurately than is possible with the average fuel-heated furnace and this is accom plished with a minimum of attendant labour. Usually the anneal ing process may be carried out overnight which permits the use of off-peak power purchased at minimum cost and often the same furnace is used during the day for other heat-treating operations.

Electricity has been applied successfully and economically to such low-temperature industrial processes, as japanning and enamelling, core baking, glue melting, firing of glassware and sherardizing. Electric furnaces operating at temperatures in excess of i,000° F are being used for annealing, carbonizing, hardening and for vitreous enamelling. Electric heating removes all the difficulties that result from fuel combustion taking place where the heat is applied. The atmosphere in which the heating is done can be made the most suitable for the treatment given. The temperature also can be controlled exactly in all parts of the oven by the proper number and placing of the heating ele ments. These are the reasons for the small number of articles rejected by inspectors after electric heat treatment and conse quently for the saving obtained over other processes where com bustion is present and the temperature not so exactly controlled. Electric heating has also often been found to produce articles of higher quality than are produced by other methods. This is also a reason for its quite general application. The small number of rejects and the improved quality of the article are important factors in determining the cost of electric heat for various treat ments in comparison with other methods.

Electric welding both by the electric arc and the resistance method is continuously finding more application and much progress has been made in the use of the automatic electric welding machine. On articles of simple shapes and in quantity production these machines are doing work cheaply and very well. The personal equation of the operator is removed and all the elements are controlled so as to produce the best weld. Semi automatic welding machines are also finding considerable use. Here the feed of the electrode and the arc length are auto matically controlled but the travel of the arc is under hand con trol so that the machines can be used on articles of a great variety of shapes. Welding has been used on structural steel parts in the place of rivets. If arc welding should prove, after more experimentation and experience, the best method for this work, the automatic machine will find an enormous field of appli cation in the fabricating shop.

One of the recent forms of electric welding development has been that known as the atomic hydrogen weld. In this process an arc is maintained between two tungsten electrodes. A stream of hydrogen emerging from the electrode holder envelops the elec trodes and thus prevents their oxidation and at the same time acts as the heat carrier. The hydrogen molecules are dissociated by the intense heat of the arc into the atomic state. Upon strik ing the relatively cool surfaces being welded, these atoms re-com bine with the liberation of intense heat. The intensity of the heat and the complete shielding of the fused metal with hydrogen preventing contamination by the oxygen and nitrogen, results in the formation of an unusually sound, smooth and ductile weld. It makes possible the welding of many alloys that have not readily lent themselves to welding by other processes. Atomic hydrogen welding has found its principal application in the welding of light sections where appearance and ductility are of first consideration, and in the welding of special alloys.

The picture of electrification progress would be incomplete with out some reference to the recent trend toward railroad electrifica tion. (Details of this development are to be found in the article RAILWAYS.) Adequate lighting is to-day playing a very important part in our manufacturing processes and a description of this is given in the article on LIGHTING. It is impossible to treat ade quately the development of the electrification of industry under any one heading and the following articles should be referred to in addition to those cited above: ELECTRICAL POWER GENERATION; ELECTRICAL POWER TRANSMISSION ; ELECTRIC GENERATOR; MO TOR, ELECTRIC ; ELECTRIC TRACTION ; ELECTRICITY SUPPLY, COMMERCIAL AND TECHNICAL ASPECTS; ELECTRICAL POWER IN AGRICULTURE; HOUSEHOLD APPLIANCES ; IRON AND STEEL; ALLOYS ; FURNACE, METALLURGICAL ; POWER TRANSMISSION, MECHANICAL ; MACHINE-TOOLS ; METALLURGY ; PETROLEUM ; and various industrial processes under their own heading.

(H. C. TH.)