Modern European Enamels

MODERN EUROPEAN ENAMELS The cultivated taste which prompted the acquisition and col lection of the finer enamels such as those made in basse-taille, plique-a-jour, "Limoges" or painted and translucent enamels has always been confined to a few connoisseurs and patrons. And on the other hand the artists engaged in this work who have had the courage and persistence to carry on in spite of the failures inci dental to such delicate and elaborate processes have been com paratively small in number at any time. So that it is not to be wondered at that the enamels of this character and standing have not been produced in quantities especially during recent years when the patronage of the arts generally has fallen off to so great an extent. On the other hand the simpler processes of cloisonne and champleve which lend themselves readily to the decoration and enrichment of metal surfaces have been employed in many diverse ways.

The application of enamel in these processes, which are the oldest and most primitive, has been largely due to the tuition in the classes held in the Schools of Art, the municipal and County Council schools and the technical institutes in Great Britain and Ireland and to similar educational bodies which foster the Arts and Crafts in Europe, America and the British colonies. There has been no attempt made at any advance on these ancient methods. The style and treatment both of the design and process remain the same; for indeed it would be difficult to improve them. The study of the old examples in these processes has carried with it the due appreciation of the suitability and character of the design.

The desire to perpetuate the names of the fallen in the World War brought about a demand for memorials in bronze, copper and silver on which the names of the men, the shields of their native towns, the badges of the regiments and companies and other he raldic achievements were done in enamel. These memorials are to be found in the cathedrals, churches, public buildings and the chapels of the colleges and universities. Besides which there has continued to be a considerable use of enamel on the altar orna ments of the churches. And the chalices, Bible covers and lamps have occasionally been enriched with either cloisonné or plique-a jour enamels.

Again on the public presentation gifts of trophies, caskets, cups and other like ornaments there has been the suitable adornment of enamel designs. These various applications of enamel have con stituted the main output of the art worker in enamels.

These examples, however, do not leap to the eye so much as the uses to which enamel has been put in commerce and trade. The enamelled iron advertisement plates have been exhibited on the walls and hoardings for many years, and have shown no advance in either technique or colour and design, but of re cent years there has been a recognition of the beauty of the colour of enamel when artistically employed, and that this quality is of equal value to its permanence. It is effectively used in the lettering of the names of firms, of shopkeepers, with the trade mark and emblems. These have been made in translucent enamel fused over copper and silver foil or in opaque enamels in the champleve process. The great improvement in the design, spacing, drawing and form of the lettering is to be seen over shop and store windows replacing the ugly lettering and thus adding a re finement to the streets.

In the jewellers', gold and silversmiths', and fancy-goods shops a great advance had been made in the design and colour of the enamel decoration of gold and silver cigarette boxes, watches, the backs of brushes for the toilet table and indeed of all such things of a similar kind. There still remains a tendency to use an engine turned ground on the silver and gold objects over which a clear transparent enamel has been fixed. The chief reason for the engine-turning is to give a "key" to the enamel by which it obtains a firmer hold on the metal than if it were applied to a smooth surface. Most of these articles are made in Russia, Czecho Slovakia, Germany and Sweden.

Enamelling Processes.

The base of enamel is a clear, colour less, transparent vitreous compound called flux, which is com posed of silica, minium and potash. This flux or base—termed fondant in France—is coloured by the addition of oxides of metals while in a state of fusion, which stain the flux throughout its mass. Enamels are either hard or soft, according to the proportion of the silica to the other parts in its composition. They are termed hard when the temperature required to fuse them is very high. The harder the enamel the less liable is it to be affected by atmos pheric agencies, which in soft enamels produce a decomposition of the surface first and ultimately of the whole enamel. Pure— or almost pure—metals are in most respects the best to receive and retain the enamel. Enamels composed of a great amount of soda or potash, as compared with those wherein red lead is in greater proportion, are more liable to crack and are less cohesive.It is better not to use silver as a base, although it is capable of reflecting a higher and more brilliant white light than any other metal. Fine gold and pure copper as thin as possible are the best metals upon which to enamel. If silver is to be used, it should be fine silver, treated in the methods called champleve and cloisonné.

The brilliancy of the substance enamel depends upon the per fect combination and proportion of its component parts. The intimacy of the combination depends upon an equal temperature being maintained throughout its fusion in the crucible. For this purpose it is better to obtain a flux which has been already fused and most carefully prepared, and afterwards to add the colouring oxides, which stain it dark or light according to the amount of oxide introduced. Many of the enamels are changed in colour by the difference of the proportion of the parts composing the flux, rather than by the change of the oxides. For instance, turquoise blue is obtained from the black oxide of copper by using a com paratively large proportion of carbonate of soda, and a yellow green from the same oxide by increasing the proportionate amount of the red lead. All transparent enamels are made opaque by the addition of calx, which is a mixture of tin and lead calcined. White enamel is made by the addition of stannic and arsenious acids to the flux. The amount of acid regulates the density or opacity of the enamel.

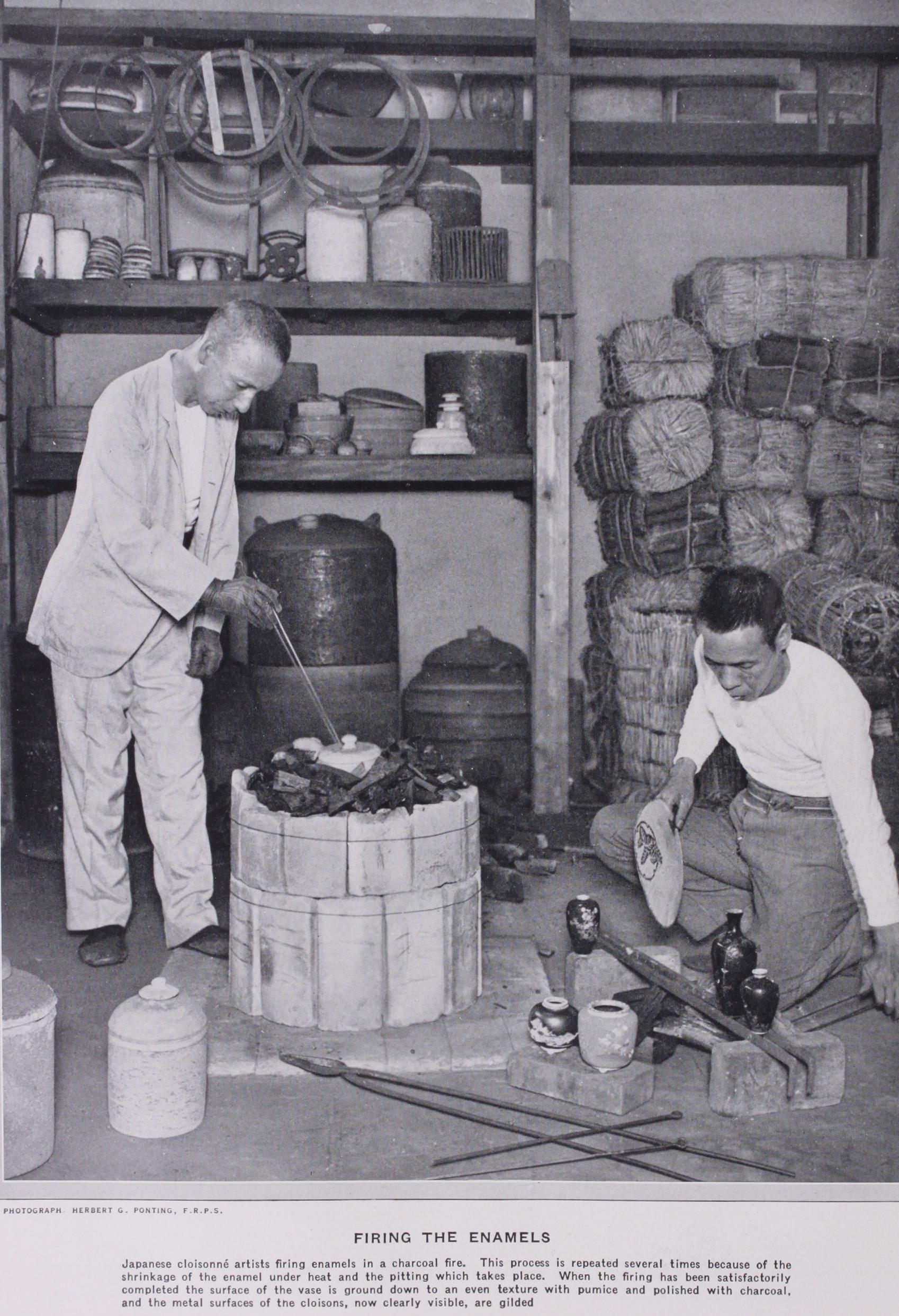

After the enamel has been procured in the lump, the next stage in the process, common to all methods of enamelling, is to pul verize it. To do this properly the enamel must first be placed in an agate mortar and covered with water; next, with a wooden mallet a number of sharp blows must be given to a pestle held vertically over the enamel, to break it ; then holding the mortar firmly in the left hand, the pestle must be rotated with the right, with as much pressure as possible on the enamel, grinding it until the particles are reduced to a fine grain. The powder is then subjected to a series of washings in distilled water, until all the floury particles are removed. After this the metal is cleaned by immersion in acid and water. For copper, nitric acid is used; for silver, sulphuric, and for gold, hydrochloric acid. All trace of acid is then removed, first by scratching with a brush and water, and finally by drying in warm oak sawdust. After this the pulverized enamel is carefully and evenly spread over those parts of the metal designed to receive it, in sufficient thickness just to cover them and no more. The piece is then dried in front of the furnace, and when dry is placed gently on a fire-clay or iron planche, and introduced carefully into the muffle of the furnace, which is heated to a bright pale red. It is now attentively watched until the enamel shines all over, when it is withdrawn from the furnace. The firing of enamel, unlike that of glass or pottery, takes only a few minutes, and in nearly all processes no annealing is required.

The following are the different modes of enamelling : champleve, cloisonné, basse-taille, plique-d-jour, painted enamel, encrusted and miniature-painted. These processes were known at successive periods of ancient art in the order in which they are named. To-day they are known in their entirety. Each has been largely developed and improved. No new method has been discovered, although vari ations have been introduced into all. The most important are those connected with painted enamels, encrusted enamels and plique-a jour.

Chanplevo enamelling is done by cutting away troughs or cells in the plate, leaving a metal line raised between them, which forms the outline of the design. In these cells the pulverized enamel is laid and then fused ; afterwards it is filed with a corun dum file, then smoothed with a pumice stone and polished by means of crocus powder and rouge.

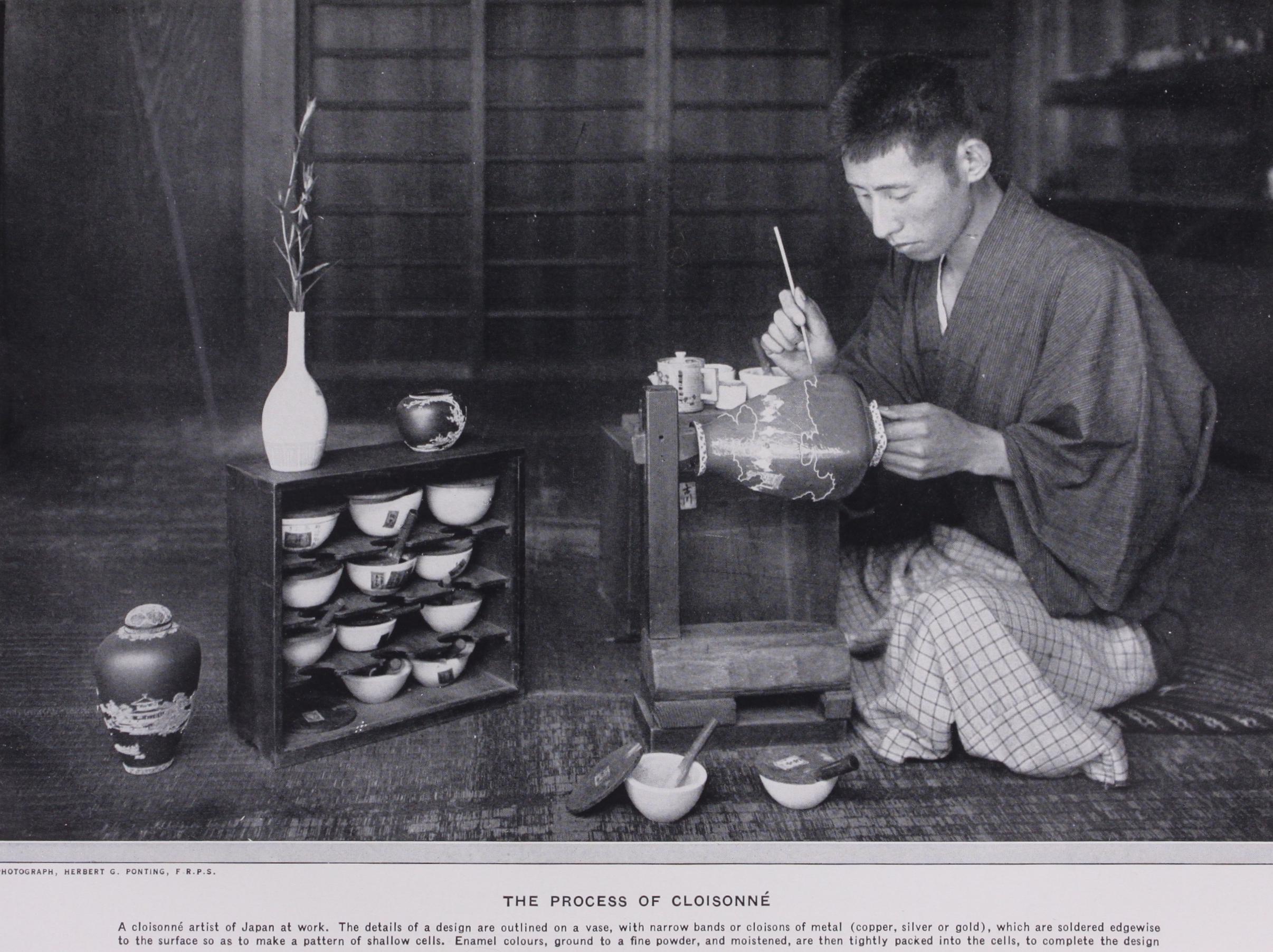

In cloisonné enamel, upon a metal plate or shape, thin metal strips are bent to the outline of the pattern, then fixed by silver solder or by the enamel itself. These strips form a raised outline, giving cells as in the case of champleve. The rest of the process is identical with that of champleve enamelling.

The basse-taille process is also a combination of metal work in the form of engraving, carving and enamelling. The metal, either silver or gold, is engraved with a design, and then carved into a bas-relief (below the general surface of the metal like an Egyptian bas-relief) so that when the enamel is fused it is level with the uncarved parts of the metals, and the design shows through the transparent enamel.

Plique-a-jour enamelling is done in the same way as cloisonne enamelling, except that the wires or strips of metal which enclose the enamel are not soldered to the metal base, but are soldered to each other only. Then these are simply placed upon a sheet of platinum, copper, silver, gold or hard brass, which, after the enamel is fused and sufficiently annealed and cooled, is easily removed.

Painted enamels are different from any of these processes both in method and in result. The metal in this case is either copper, silver or gold, but usually copper. It is cut with shears into a plate of the size required, and slightly domed with a burnisher or hammer, after which it is cleaned by acid and water. Then the enamel is laid equally over the whole surface both back and front, and afterwards "fired." The first coat of enamel being fixed, the design is carried out, first by laying it in white enamel or any other which is opaque and most advantageous for subsequent coloration.

In the case of a grisaille painted enamel the white is mixed with water or turpentine, or spike oil of lavender, or essential oil of petroleum (according to the taste of the artist) and the white is painted thickly in the light parts and thinly in the grey ones over a dark ground, whereby a slight sense of relief is obtained and a great degree of light and shade.

In coloured painted enamels the white is coloured by transparent enamels spread over the grisaille treatment, parts of which when fired are heightened by touches of gold, usually painted in lines. Other parts can be made more brilliant by the use of foil, over which the transparent enamels are placed and then fired.

Miniature enamel painting is not true enamelling, for after the white enamel is fired upon the gold plate, the colours used are not vitreous compounds—not enamels in fact—as is the case in any other form of metal enamelling; but they are either raw oxides or other forms of metal, with a little flux added, not combined. These colours are painted on the white enamel, and afterwards made to adhere to the surface by partially fusing the enamel, which when in a state of partial fusion becomes viscous.

Amongst the chief workers in the modern revival are Claudius Popelin, Alfred Meyer, Paul Grandhomme, Fernand Thesmar, Hubert von Herkomer (1849-1914), Alexander Fisher (1864 1936 ), P. Oswald Reeves and Harold Stabler. The work of Claudius Popelin shows technical skill, correctness and a careful copying of the old masters and so it suffers from a lack of invention and individuality. His work was devoted to the rendering of mythological subjects and fanciful portraits of historical people. Alfred Meyer and Grandhomme are both accomplished and care ful enamellers; the former is a painter enameller and the author of a book dealing technically with enamelling. Grandhomme paints mythological subjects and portraits in a very tender manner, with considerably more artistic feeling than either Meyer or Popelin. There is a specimen of his work in the Luxemburg Museum. Fer nand Thesmar is the great reviver of plique-a- jour enamelling in France. Specimens of his work are possessed by the art museums throughout Europe, and one is to be seen in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. They are principally valued on account of their perfect technical achievement. Lucien Falize was an employer of artists and craftsmen, and to him we are indebted for the production of specimens of basse-taille enamel upon silver and gold, as well as for a book reviewing the revival of the art in France, bearing particularly on the work of Claudius Popelin. Until within recent years there was a clear division between the art and the crafts in the system of producing art objects. The artist was one person and the workman another. It is now acknowledged that the artist must also be the craftsman, especially in the higher branches of enamelling. Falize initiated the produc tion of a gold cup which was enamelled in the basse-taille manner. The band of figures was designed by Olivier Merson, the painter, and carved by a metal carver and enamelled by an enameller, both able craftsmen employed by Falize. Other pieces of enamelling in champleve and cloisonne were also produced under his super vision but on this system ; therefore lacking the one quality which would make them complete as an expression of artistic emo tion by the artist's own hands. Rene Lalique is among the jewel lers who have applied enamelling to their work in a peculiarly technically perfect manner.