Modern Theory of Polarity

MODERN THEORY OF POLARITY Until recently the source of the opposite electric charges on the ions of dissociated compounds remained obscure, but their origin has now been satisfactorily explained from a consideration of the physical theories which have been developed to account for the structure of the atom. According to present theories which have been developed by J. J. Thomson (Phil. Mag. 1914), Kossel (Ann. Physik, 1916), G. N. Lewis (J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1916), and I. Langmuir (Ibid., 192o), the atom consists of a nucleus which remains unaltered in all ordinary chemical changes, .and possesses an excess of positive charges corresponding in number to the ordinal number of the group in the periodic table to which the element belongs (see PERIODIC LAW) . The nucleus is surrounded by negative charges or electrons which, on the Lewis-Langmuir theory are maintained in definite positions through the equilibrium between the opposing influences of the electrostatic attraction of the central charge and the mutual repulsion of the ions (see VALENCY) . A further factor which operates in this equilibrium is a force of repulsion which appears between nucleus and ion at very short intervals of separation. The number of electrons in the outer layers are, in the neutral atom, equal in number to the excess of positive charge of the nucleus, but the number of elec trons in the shell may vary during chemical change between o and 8. A group of eight electrons forms a complete shell and, accord ing to the number of these shells, gives one of the inert elements, helium, neon, argon, krypton or xenon. All atoms tend to attain the electron configuration of the inert gases, because these con figurations are the most stable ; therefore all atoms attempt, either to give up all the valence electrons (electro-positive valence) so that each arrives at the electron number of the proceeding inert gas, or to take on so many electrons that the outer electron group will be brought up to the number of electrons of the next higher inert gas. Chemical attraction between two atoms may accordingly arise from one or two mechanisms. (I) The tendency of one atom to complete its shell of electrons at the expense of a second atom, thus leaving one atom with an excess of positive charges and the second with an excess of negative charges. The electrostatic at traction thus produced maintains the combination. The number of electrons which may be detached or acquired by this process is a measure of the valency of the element. This type of union occurs in such a compound as hydrogen chloride, the hydrogen having released its single electron to supplement the seven elec trons around the chlorine and complete its octet. On account of the unsymmetrical nature of the hydrogen atom the electron is readily lost, leaving the residue a positively charged hydrogen ion. (2) The atoms may orientate themselves in such a manner that from one to four electrons of each atom may be shared or held in common in the structure of both atoms. In this way the shells of electrons are completed to form stable groups without disturbing the electrical neutrality of the system.

In the first type of combination the valence electron is almost completely removed from the one atom and enters the assemblage of the other. Such compounds, which are said to be hetero-polar or polar, and decompose with relative ease into ions, are held together mainly by Coulombian electrostatic forces. In the second type, sometimes known as covalency, the valence electrons describe such orbits in the compound that they belong equally to both atoms ; since these atoms have the same electric charge, such com pounds are called homopolar or non-polar. They show no tendency to dissociate into ions. A large portion of the chemical compounds can be classified in these two limiting groups without much difficulty. Rigorously homo-polar compounds exist only in the union between the two atoms of the same species such as in 02 N2. As soon as different kinds of atoms combine, some dissymmetry in the division of the electric charges can always be observed by such means as the existence of an infra-red spectrum. The difference between the above two types can thus only be regarded as one of degree and not of kind.

According to a representation of Lewis and Randall (J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1921), if we have a uni-univalent electrolyte whose cation is M and whose anion is X, the molecule may be repre sented by the formula M:X:, where the pairs of dots represent the valence electrons, or the electrons of the outer shells. The pair lying between the atomic nuclei M and X constitutes the chemical bond. In the weak electrolytes, like acetic acid or mercuric chloride, this approximates to the typical bond of organic chem istry, but as we pass to stronger electrolytes the nucleus of the cation draws away from this bonding pair until, in the limit, this electron pair may be regarded as the property of the anion alone. Then the positive ion, which is the nucleus M is held to sym metrical anion :X: only by the fact that they are oppositely charged. When an electrolyte in a strongly polar or electrophilic medium approximates this condition it may be classified as a strong electrolyte.

Polarity.—The property of solutions of forming electrolytic conductors is associated with a classification which may be drawn between compounds according to whether they may be regarded as polar or non-polar. The distinction between these two classes is one of degree only and not of type, and depends not only on the constitution of the compound but on the medium in which it is dissolved. In comparison with non-polar compounds, the polar compounds are characterized by possessing a high degree of ionization or a good ionizing power as solvents, high dielectric constants, power of association, tautomerism, being electrophilic and forming molecular complexes.

Polarity of a molecule arises from the fact that in a molecular structure formed by interchange of electrons, although the charge of the nucleus is balanced by the surrounding electrons, yet on account of the unsymmetrical structure of the molecule the centre of the positive charges does not necessarily coincide with that of the negative ones, so that the molecule has a definite electric moment. There is thus a stray field of force around the molecule and a bipole is formed, one side of the molecule being more positive or negative than the other. The molecule will thus attract and be attracted by other molecules. If the molecules of solvent possess a similar property, the negative side of one molecule will be attracted by the positive side of another and a definite electro static attraction exhibited which is shown as residual valency. When displacement of an electron occurs, and the charged parts of the molecule are separated by an appreciable distance, a bipole (or multi pole) of high electric moment is obtained and its force of attraction for another molecular bipole will be felt over a considerable intervening distance.

The part played by the solvent in dissociation is shown in that a bipole of small molecular moment which would scarcely attract a similar molecule, will be very appreciably attracted by a polar molecule or bipole of high moment and may form with it a double molecule. In general, if two molecules combine or even approach one another, each weakens the constraints which hold together the charge of the other, and the electrical moment of each is increased. This effect is cumulative in that, when two molecules by their approach or combination become more polar they draw other molecules more strongly towards them and this increases still further their polar character. The polar character of a substance thus depends not only upon the specific properties of the individual molecules but also upon what may be termed the strength of the polar environment.

According to the octet theory of valency, strong bases such as potassium hydroxide, barium hydroxide and all typical salts are to be regarded as completely ionized even in the solid con dition. In the hydrochloric acid molecule the properties may be explained by regarding the hydrogen nucleus as sharing a pair of electrons with the chlorine atom. Anhydrous liquid hydrogen chloride is, therefore, a non-conductor of electricity since there are no free ions. In contact with water, however, separation of the molecule into ions occurs, which may be explained either from a consideration of the dielectric effect of the solvent, or else by regarding the hydrogen nucleus as attaching itself more easily to the unshared pairs of electrons in the octets of the water molecules than to the chlorine atoms, since the nuclei of the oxygen atoms have smaller positive charges than those of the chlorine atoms. The result is that the hydrogen nuclei become hydrated hydrogen ions, and the chlorine ions remain in solution. With a weak acid such as hydrogen sulphide, the tendency for the hydrogen nucleus to separate from the octet is very much less, which may be explained by the smaller positive charge on the nucleus of the sulphur atom causing the hydrogen nucleus to be much more firmly held. From this viewpoint, acids are thus to be regarded as substances from whose molecules hydrogen nuclei are readily abstracted, while bases are substances whose molecules can easily take up hydrogen nuclei.

Dielectric Constant.

The difference between polar or highly ionized and non-polar or slightly ionized compounds is reflected in the dielectric constant which measures the number of free charges in the substance multiplied by the average distance through which these charges move under the influence of a def inite electric field. It was enunciated by J. J. Thomson and independently by Nernst in 1893 that the ionizing power of a solvent is closely connected with its dielectric constant. This effect follows from Coulomb's law in which f = D el2 2 where f represents the attracting or repelling force of unlike or like charges of electricity, and the electric charges which are separated by the distance land D the dielectric constant.In a detailed investigation made by Walden (Z. Physik. Chem., 1903, 1906) the dissociating power of a very large number of organic liquids for the solute tetra ethyl ammonium iodide was measured, and it was found that a close parallelism exists be tween the dielectric constant of the solvent and the percentage dissociation of the solute. An empirical relation which was found to apply is given by the equation D = constant where c is the concentration at which the degree of ionization of the solute has a definite value in any solvent. It was found by Walden that the value of the dielectric constant of liquids is determined by certain groups. By the substitution of the follow ing groups the magnitude of the incre se of dielectric constant becomes greater in the following order :-- I, Br, Cl, CN, CHO, CO, NO2, OH.

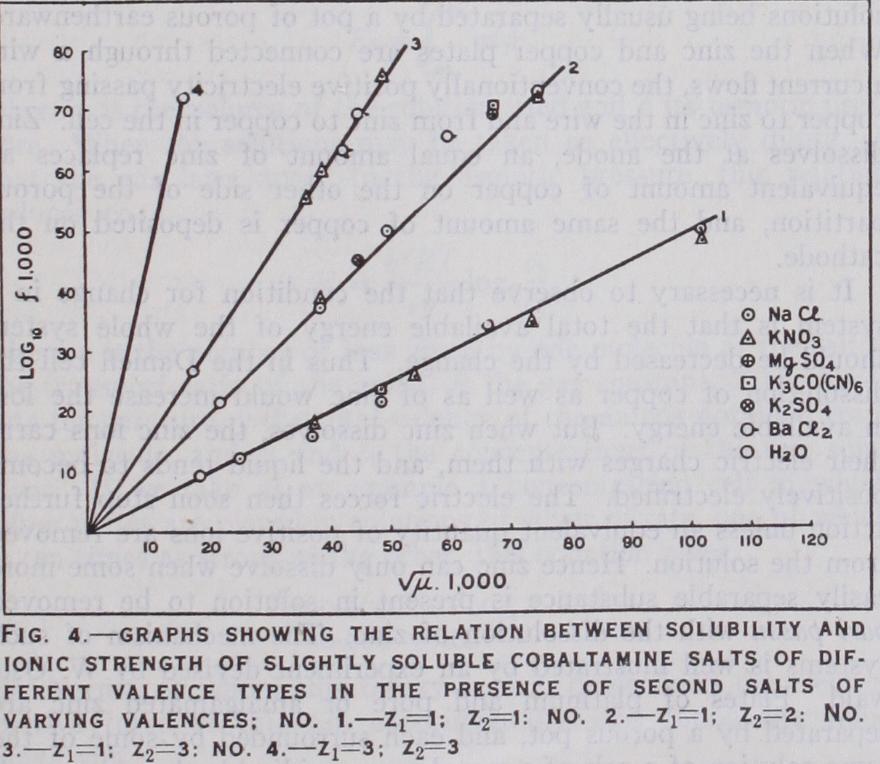

According to the theory of Debye and Huckel the magnitude of inter-ionic effects is proportional to as shown in equation (i8a), and consequently should be most marked in solvents of low dielectric constant. The solvent cyclohexanol, for instance, has a dielectric constant of 15, so that r — ck and -ln f should be times greater than in water. Lithium salts are sufficiently soluble in cyclohexanol to determine the freezing point depression, and the molar freezing-point constant (38.3°C) is twenty times that of water (i •86 °) . The results obtained are in close agreement with those required by the theory.

Voltaic Cells.

When two metallic conductors are placed in an electrolyte a current will flow through a wire connecting them, provided that a difference of any kind exists between the two conductors in the nature either of the metals or of the portions of the electrolyte which surround them. A current can be obtained by the combination of two metals in the same electrolyte, of two metals in different electrolytes, of the same metal in dif ferent electrolytes or of the same metal in solutions of the same electrolyte at different concentrations. In accordance with the principles of energetics (q.v.), any change which involves a de crease in the total available energy of the system will tend to occur, and thus the necessary and sufficient condition for the production of electromotive force is that the available energy of the system should decrease when the current flows.In order that the current should be maintained and the elec tromotive force of the cell remain constant during action, it is necessary to ensure that the changes in the cell, chemical or other, which produce the current should neither destroy the dif ference between the electrodes, nor coat either electrode with a non-conducting layer through which the current cannot pass. As an example of a fairly constant cell we may take that of Daniell, which consists of the electrical arrangement—zinc I zinc sulphate solution I copper sulphate solution I copper—the two solutions being usually separated by a pot of porous earthenware. When the zinc and copper plates are connected through a wire a current flows, the conventionally positive electricity passing from copper to zinc in the wire and from zinc to copper in the cell. Zinc dissolves at the anode, an equal amount of zinc replaces an equivalent amount of copper on the other side of the porous partition, and the same amount of copper is deposited on the cathode.

It is necessary to observe that the condition for change in a system is that the total available energy of the whole system should be decreased by the change. Thus in the Daniell cell the dissolution of copper as well as of zinc would increase the loss in available energy. But when zinc dissolves, the zinc ions carry their electric charges with them, and the liquid tends to become positively electrified. The electric forces then soon stop further action unless an equivalent quantity of positive ions are removed from the solution. Hence zinc can only dissolve when some more easily separable substance is present in solution to be removed pari passu with the dissolution of zinc. The mechanism of such systems is well illustrated by an experiment devised by W. Ost wald. Plates of platinum and pure or amalgamated zinc are separated by a porous pot, and each surrounded by some of the same solution of a salt of a metal more oxidizable than zinc, such as potassium. When the plates are connected together by means of a wire no current flows and no appreciable amount of zinc dissolves, for the dissolution of zinc would involve the separation of potassium and a gain in available energy. If sulphuric acid be added to the vessel containing the zinc, these conditions are unaltered and still no zinc is dissolved. But on the other hand if a few drops of acid be placed in the vessel with the platinum, bubbles of hydrogen appear and a current flows, zinc dissolving at the anode, and hydrogen being liberated at the cathode. In order that positively electrified ions may enter a solution, an equivalent amount of other positive ions must be removed or negative ions be added, and for the process to occur spontaneously the possible action at the two electrodes must involve a decrease in the total available energy of the system.

Concentration Cells.

As stated above, an electromotive force is set up whenever there is a difference of any kind at two electrodes immersed in electrolytes. In ordinary cells the differ ence is secured by using two dissimilar metals, but an electro motive force exists if two plates of the same metal are placed in solutions of different substances or of the same substance at dif ferent concentrations. In the latter case the tendency of the metal to dissolve in the more dilute solution is greater than its tendency to dissolve in the more concentrated solution, and thus there is a decrease in available energy when metal dissolves in the dilute solution and separates in equivalent quantity from the con centrated solution. An electromotive force is therefore set up in this direction, and if we can calculate the change in available energy due to the processes of the cell we can foretell the value of the electromotive force. Now the effective change produced by the action of the current is the concentration of the more dilute solution by the dissolution of metal in it, and the dilution of the originally stronger solution by the separation of metal from it. We may imagine these changes reversed in two ways. We may evaporate some of the solvent from the solution which has be come weaker, and thus reconcentrate it, condensing the vapour on the solution which had become stronger. By this reasoning Helm holtz showed how to obtain an expression for the work done. On the other hand we may imagine the processes due to the electrical transfer to be reversed by an osmotic operation. Solvent may be supposed to be squeezed out from the solution which has be come more dilute through a semi-permeable wall, and through another such wall allowed to mix with the solution which in the electrical operation had become more concentrated. Again, we may calculate the osmotic work done, and if the whole cycle of operations be supposed to occur at the same temperature, the osmotic work must be equal and opposite to the electrical work of the first operation.The result of the investigation shows that the electrical work Ee is given by the equation pz Ee = f vdp pl where v is the volume of the solution used and p its osmotic pres sure. When the solutions may be taken as effectively dilute, so that the gas laws apply to the osmotic pressure, this relation reduces to Y n ci E = log€ ey C: where n is the number of ions given by one molecule of the salt, r the transport ratio of the anion, R the gas constant, T the abso lute temperature, y the total valency of the anions obtained from one molecule, and ci and the concentrations of the two solu tions. If we take as an example a concentration cell in which silver plates are placed in solutions of silver nitrate, one of which is ten times as strong as the other, this equation gives E= o•o6o X I c.g.s. units =0.060 volts.

W. Nernst, to whom this theory is due, determined the electro motive force of this cell experimentally, and found the value 0.055 volt.

The logarithmic formulae for these concentration cells indicate that, theoretically, their electromotive force can be increased to any extent by diminishing without limit the concentration of the mrre dilute solution, log then becoming very great. This condition may be realized to some extent in a manner that throws light on the general theory of the voltaic cell. Let us consider the arrangement—silver silver chloride with potassium chloride solution potassium nitrate solution I silver nitrate solution l silver. Silver chloride is a very insoluble substance, and here the amount in solution is still further reduced by the presence of excess of chlorine ions of the potassium salt. Thus silver, at one end of the cell in contact with many silver ions of the silver nitrate solution, at the other end is in contact with a liquid in which the concentration of those ions is very small indeed. The result is that a high electromotive force is set up, which has been calculated as 0.52 volt, and observed as 0.51 volt. Again, Hittorf has shown that the effect of a cyanide round a copper electrode is to com bine with the copper ions. The concentration of the simple copper ions is then so much diminished that the copper plate becomes an anode with regard to zinc. Thus the cell—copper potassium cy anide solution I potassium sulphate solution—zinc sulphate solu tion zinc—gives a current which carries copper into solution and deposits zinc. In a similar way silver could be made to act as anode with respect to cadmium.

It is now evident that the electromotive force of an ordinary chemical cell such as that of Daniell depends on the concentration of the solutions as well as on the nature of the metals. In ordi nary cases possible changes in the concentrations only affect the electromotive force by a few parts in a hundred, but by means such as those indicated above it is possible to produce such im mense differences in the concentrations that the electromotive force of the cell is not only changed appreciably but even re versed in direction. Any reversible cell can theoretically be employed as an accumulator, though in practice conditions of general convenience are more sought after than thermodynamic efficiency (see ACCUMULATOR.) The reversibility of a cell is in general modified by the phenomenon of polarization (see ELECTRO