Monumental Effigies

EFFIGIES, MONUMENTAL, a term usually associated with the figures carved in relief, or in the round, on the sepulchral monuments of the Christian era. However, close prototypes may be found on the Etruscan sarcophagi, which in some cases date as far back as the 6th or 5th century B.C. In the Flavian period, Ulpia Epigone is represented in relief in precisely the same manner as on Italian tombs of the i 5th century. Portrait busts are found on the fronts of the early Christian sarcophagi, but full length carved effigies appear to be completely non-existent between the Roman period and the 11th century A.D. It is possible that royal, and perhaps some of the most important ecclesiastical effigies, were comparatively faithful portraits as early as the 14th century, but other effigies before the 15th century were probably made from stock workshop patterns. The details of costume seem to have been most carefully reproduced and form an extremely valuable contribution to our knowledge of the attire of the dif ferent periods. The materials used for the effigies varied, marble and bronze being used throughout Europe, stone and wood chiefly in the more northern countries, the latter being particularly well represented in England. Purbeck marble was largely used in England for the earlier figures, and alabaster during the 15th century.

Romanesque and Gothic.

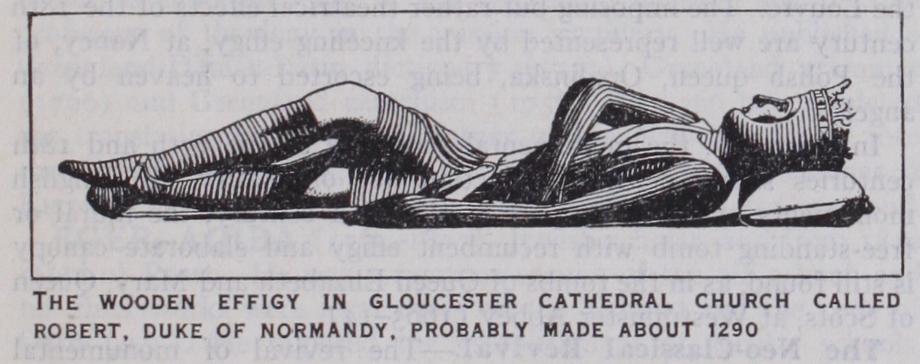

The characteristic sepulchral monument throughout northern Europe in the 12th century is the flat slab tomb with the effigy in low, later in higher, relief. With the 13th century the base frequently takes the form of a sar cophagus, the decoration of which becomes gradually more elabo rate and which is sometimes surmounted by an architectural canopy. Though horizontal, the figure in the earlier tombs is rep resented standing, but in the 13th century assumes a recumbent position, some of the earliest examples of the change being found in France. The upright position is, however, characteristic of the whole period in Germany.Flat slab monuments are perhaps the most characteristic form throughout the Gothic period in Germany, those of the 14th century being well represented at Bamberg, and there is a long series of effigies, extending over several centuries, at Mainz. Slab tombs of the 12th century in France generally follow the same lines as in Germany but are much more rare. The ments of the 13th and 14th centuries follow the usual develop ment, the effigy being treated in increasingly high relief and fre quently supported on a tomb chest with or without an architec tural canopy. Unfortunately the unrivalled series of royal effigies at St. Denis have suffered severely from restoration but they still form a most valuable record. The few remaining 12th century tombs in England are of the usual slab form with the figure in low relief, but the series of effigies of the 13th century, mainly carved in Purbeck marble, are exceptionally rich in quantity and vigorous in style. A distinct group of effigies is that representing knights in chain-mail; after the middle of the century the legs are usually crossed but there seems to be no foundation for the popular theory that this position indicates a crusader. A notable group of such effigies is in the Temple church in London. Another fine example is the wooden effigy, at Gloucester, called Robert, Duke of Normandy (c. 129o). After the middle of the century miniature chapels and shrines were frequently built up over the tomb, a good example being the monument of Bishop Giles Brid port at Salisbury. The whole series of effigies, from the late Romanesque to the end of the Gothic period form, both in num ber and variety, one of the most characteristic developments of English sculpture. The flat slab tombs of the 12th and 13th cen turies of northern Europe are not frequent in Italy. A very characteristic type of mural monument was evolved by the Cos mati school, chiefly in Rome, in the second half of the 13th century; this shows the recumbent effigy on a high draped sar cophagus, frequently inlaid with mosaic, under an arched canopy with, in most cases, a fresco or mosaic of the Virgin and Child in the lunette. But to Arnolfo di Cambio (c. 1232-1300) is due a very fine development of this composition, the monument of Cardinal de Braye at Orvieto, the prototype of the magnificent series of 15th century monuments, which are one of the glories of Italian art.

The Renaissance.

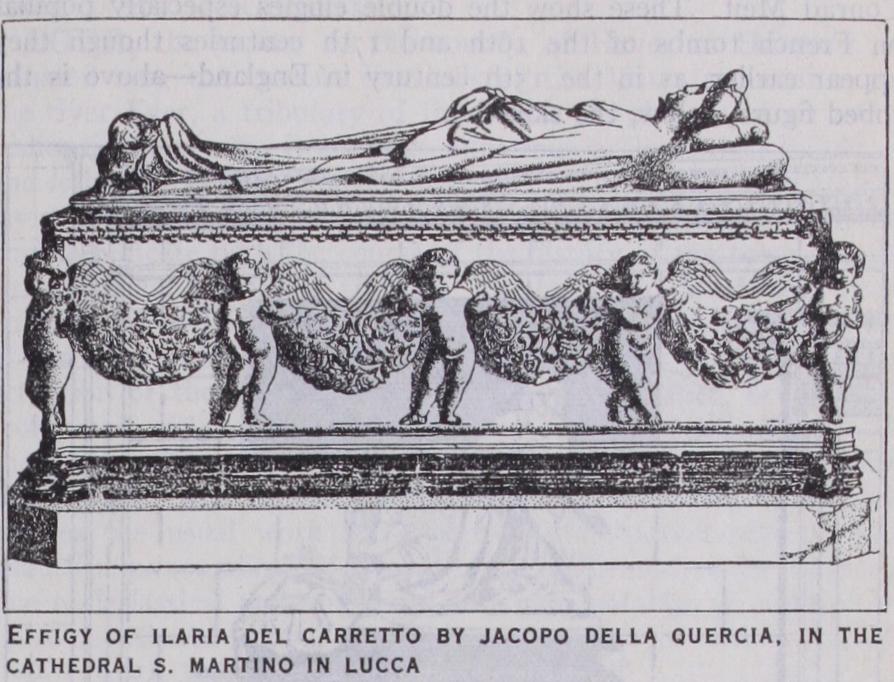

The long series of 15th and i6th century tombs in Italy embrace some of the finest Italian figure sculpture and they were frequently the work of the foremost artists of the day. Few works of art are more moving than the lovely effigies of Santa Justina by Agostino di Duccio (now at South Kensington museum, London), or of Ilaria del Carretto, at Lucca, this latter by Jacopo della Quercia. The typical Tuscan form of the I5th century is the mural .monument showing the recumbent portrait effigy lying on a bier supported on a sarcophagus with a relief of the Virgin and Child above in the lunette under the round arched frame. To the first quarter of the i6th century belongs the masterpiece of late Renaissance monumental sculpture in Italy, the tombs of the Medici by Michelangelo in San Lorenzo at Florence. The two seated effigies are idealized figures rather than portraits, but the whole conception is one of the noblest works of Italian art and one which exercised an overpowering influence on most of the remaining tombs of the century.The style of the transitional Gothic-Renaissance period finds expression in Germany in the magnificent tombs of Margaret of Austria and Philibert of Savoy (c. 1526-32) at Brou, by Conrad Meit. These show the double effigies especially popular on French tombs of the i6th and 17th centuries though they appear earlier, as in the i 5th century in England—above is the robed figure, below, the skeleton.

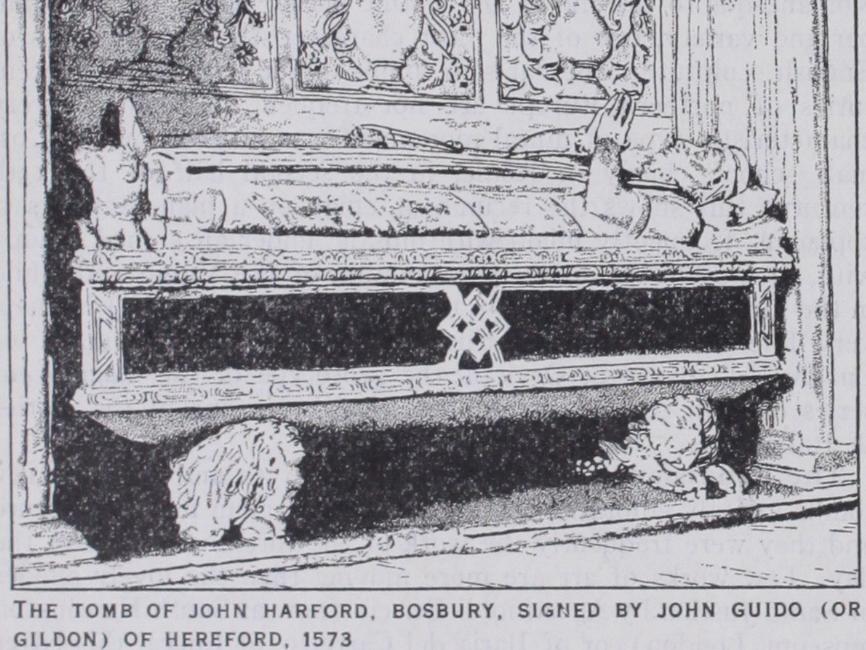

In the first half of the i6th century some very elaborate free standing and mural monuments were produced in France. The effigies are usually shown kneeling or reclining as in life. A typi cal example of the mural tomb with minutely characterized kneeling figures is the monument of the Cardinals d'Amboise at Rouen. One of the most magnificent of the huge free-standing monuments is that of Henry II. and Catherine de' Medici at St. Denis (1563-7o) by Germain Pilon. In England, the recumbent effigy is still the usual form on tombs of the transitional Gothic Renaissance period, the most characteristic type of monument being perhaps the large free-standing tomb chest without an archi tectural canopy.

Baroque.

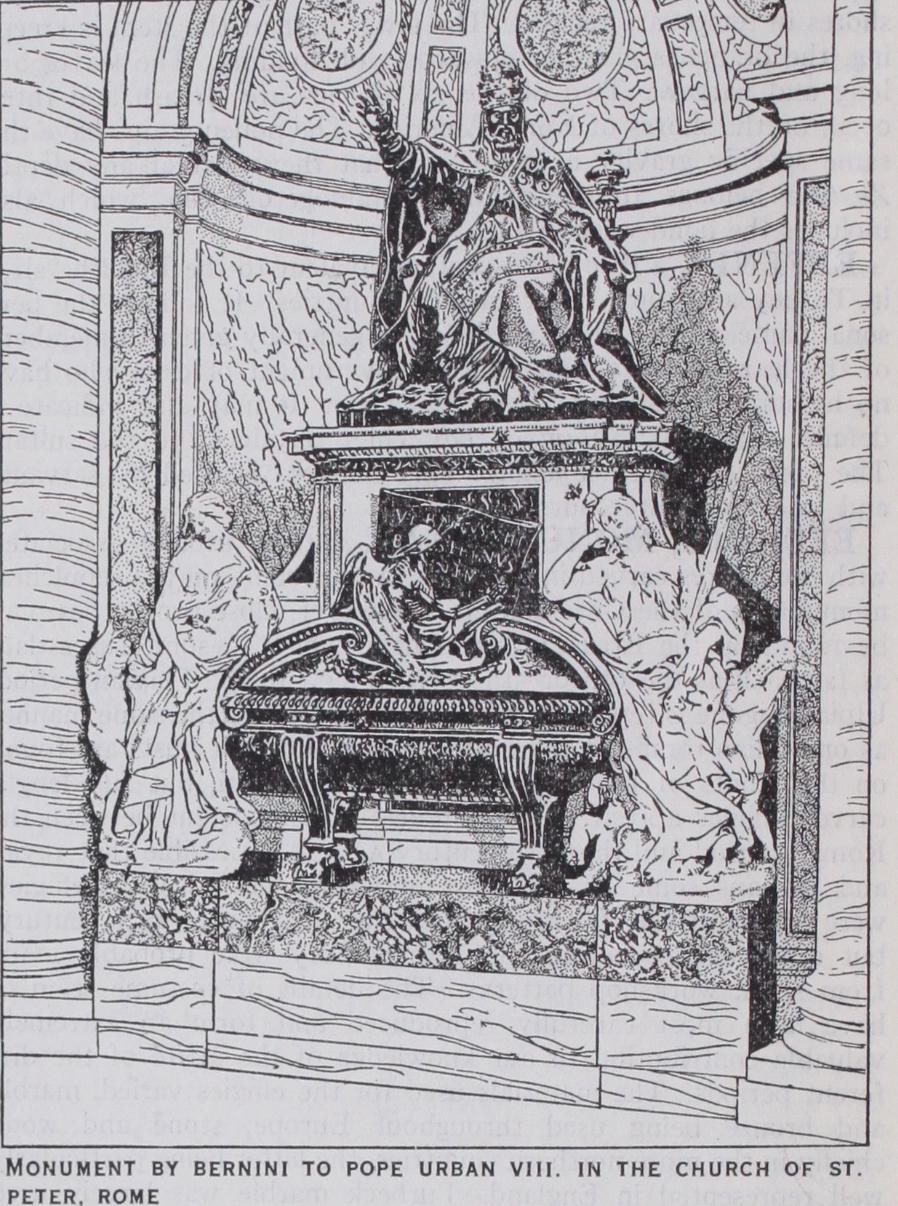

If Michelangelo's design for the Medici tombs was the dominating factor in the monumental style of the 16th century in Italy, Bernini's tombs of the popes at St. Peter's, Rome, are characteristic for the 17th and i8th centuries.

In

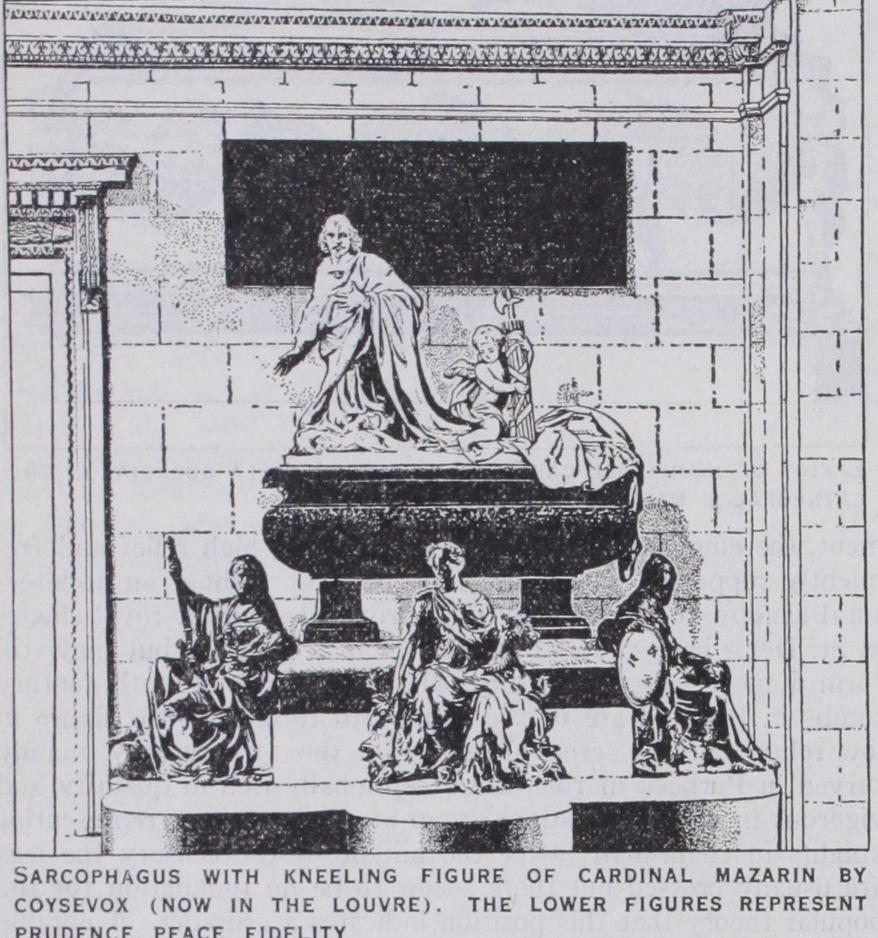

France, a distinct change comes over the treatment of the effigy in the I7th century ; hitherto the figure has been repre sented in repose, but with the i 7th century emotion and dra matic feeling are aimed at. The tomb of Richelieu at the Sor bonne in Paris, by Girardon, with its weeping mourner, is a case in point, as, too, is the gesticulating reclining effigy of Turenne by Tuhy at the Invalides. Really fine, however, is the very life like kneeling figure of Mazarin, by Coysevox, on his tomb now in the Louvre. The imposing but rather theatrical effects of the i8th century are well represented by the kneeling effigy, at Nancy, of the Polish queen, Opalinska, being escorted to heaven by an angel.

In Germany, the monumental sculpture of the 17th and 18th centuries shows neither distinction nor originality. In English monuments of the early part of the 17th century, the mural or free-standing tomb with recumbent effigy and elaborate canopy is still found, as in the tombs of Queen Elizabeth and Mary, Queen of Scots, at Westminster Abbey (1603-12).