Suez Canal

SUEZ CANAL).

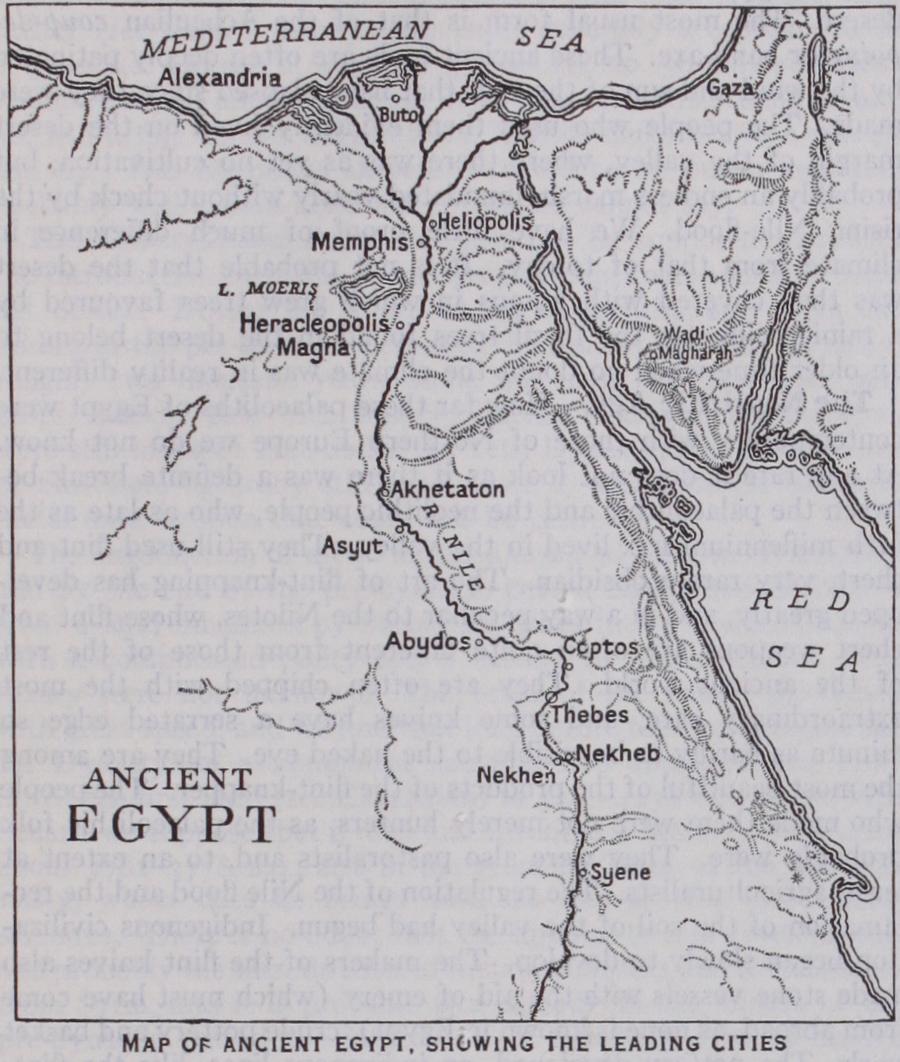

A chain of natron lakes (seven in number) lies in a valley in the western desert, 70 to 90 m. W.N.W. of Cairo. In the Fayum province farther south is the Birkat Qaroun, some 3o m. long and 5 wide at its broadest part, being all that now represents the storied Lake of Moeris. Near the lake are several sites of ancient towns, and the temple called Kasr-Karun, dating from Roman times, distinguishes the most important of these.

The Desert Plateaux.—From the southern borders of Egypt to the Delta in the north, the desert plateaux extend on either side of the Nile valley. The eastern region, between the Nile and the Red sea, varies in width from 90 to 35o m. and is known in its northern part as the Arabian desert. The western region has no natural barrier for many hundreds of miles; it is part of the vast Sahara. North of Aswan it is called the Libyan desert. In the north the desert plateaux are comparatively low, but from Cairo southwards they rise to i,000 and even 1,500 ft. above sea-level. The weathering of this desert area is probably fairly rapid, the agents at work being principally the rapid heating and cooling of the rocks by day and night, and the erosive action of sand laden wind on the softer layers; these, aided by the occasional rain, are ceaselessly at work, and produce the successive plateaux, dotted with small isolated hills and cut up by valleys (wadis) which occasionally become deep ravines, thus forming the prin cipal type of scenery of these deserts. East of the Nile the desert meets the line of mountains which runs parallel to the Red sea and the Gulf of Suez. In the western desert, however, those large sand accumulations which are usually associated with a desert are met with. They occur as long, narrow lines of dunes formed of rounded grains of quartz, lying in the direction of the prevalent wind ; in places they cover immense areas, rendering them abso lutely impassable except in a direction parallel to the lines them selves. East of the oases of Baharia and Farafra is a very striking line of these sand dunes; rarely more than 3 m. wide, it extends for a length of nearly 55o miles.

Oases.—In the western desert lie the five large oases of Egypt, namely, Siwa, Baharia, Farafra, Dakhla and Kharga or Great oasis, occupying depressions in the plateau or, in the case of the last three, large indentations in the face of limestone escarpments which form the western versant of the Nile valley hills. Their fertility is due to a plentiful supply of water furnished by a sand stone bed 30o to 500 ft. below the surface, whence the water rises through natural fissures or artificial boreholes. These oases were known and occupied by the Egyptians as early as 160o B.C., and Kharga rose to special importance at the time of the Persian oc cupation. Here, near the town of Kharga, the ancient Hebi, is a temple of Ammon built by Darius I., and in the same oasis are other ruins of the period of the Ptolemies and Caesars. The oasis of Siwa (Jupiter Ammon) is about 'so m. S. of the Mediter ranean at the Gulf of Sollum and about 30o m. W. of the Nile. The other four oases lie parallel to and distant zoo to 150 m. from the Nile, between 25° and 29° N., Baharia being the most north erly and Kharga the most southerly.

Besides the oases the desert is remarkable for two other val leys. The first is that of the natron lakes already mentioned. It contains four monasteries, the remains of the famous anchorite settlement of Nitriae. South of the Wadi Natron, and parallel to it, is a sterile valley called the Bahr-bela-Ma, or "River without Water." The Sinai Peninsula.—The triangular-shaped Sinai peninsula has its base on the Mediterranean, the northern part being an arid plateau, the desert of Tih. The apex is occupied by a massif of crystalline rocks, which rise bare and steep (in places to a height of over 8,500 ft.) from the valleys and support hardly any vegetation. In some of the valleys wells or rock-pools filled by rain occur, and furnish drinking-water to the few Arabs who wander in these hills.

Geology.

The oldest formation in the eastern part of the country is a great tract of uneven crystalline schists, which runs from the Sinai peninsula to the north border of Abyssinia. Over lying the crystalline rock in this area is a thick volcanic series, in which are numerous intrusions of granite, which furnished the chief material for the ancient monuments. At Aswan (Syene) the well-known syenite of Werner occurs. It is, however, a hornblende granite and does not possess the mineralogical composition of the syenites of modern petrology. On the western side of the country, from Thebes to Khartoum, the crystalline formation is overlaid by Nubian sandstone, which extends westward from the river to the edge of the great Libyan desert, where it forms the bed rock. Above the sandstone in many places lie a series of clays : and over them in turn rests the thick layer of soft white lime stone which lines the Nile valley south of Cairo and furnishes fine building stone. In the Kharga oasis the upper portion con sists of variously coloured unfossiliferous clays with intercalated bands of sandstone containing fossil silicified woods (Nicolia Aegyptiaca and Araucarioxylon Aegypticum). They are con formably overlain by clays and limestones with Exogyra Over wegi belonging to the Lower Danian, and these by clays and white chalk with Ananchytes ovate of the Upper Danian. The fluvio-marine deposits of the Upper Eocene and Oligocene forma tions contain an interesting mammalian fauna ; Arsinoitherium is the precursor of the horned Ungulata ; while Moeritherium and Palaeo-mastodon undoubtedly include the oldest known ele phants. Miocene strata are absent in the southern Tertiary areas, but are present at Moghara and in the North. Marine Pliocene strata occur to the south of the pyramids of Giza and in the Fayum province, where, in addition, some gravel terraces, at a height of 50o ft. above sea-level, are attributed to the Pliocene period. The Lake of Moeris, as a large body of fresh water, appears to have come into existence in Pleistocene times. It is represented now by the brackish-water lake of the Birkat Qaroun. The superficial sands of the deserts and the Nile mud form the chief recent formations. The Nile deposits its mud over the valley before reaching the sea, and consequently the Delta receives little additional material. The superficial sands of the desert region, derived in large part from the disintegration of the Nubian sandstone, occupy the most extensive areas in the Libyan desert. The other desert regions of Egypt are elevated stony plateaux, which are diversified by extensively excavated valleys and oases. These regions present magnificent examples of dry erosion by wind-borne sand, which acts as a powerful sand blast etching away the rocks and producing most beautiful sculpturing. The rate of denudation in exposed positions is exceedingly rapid; while spots sheltered from the sand blast suffer a minimum of erosion, as shown by the preservation of ancient inscriptions. Many of the Egyptian rocks in the desert areas and at the cata racts are coated with a highly polished film, of almost micro scopic thinness, consisting chiefly of oxides of iron and manganese with salts of magnesia and lime. It is supposed to be due to a chemical change within the rock and not to deposition on the surface.

Minerals.

Egypt possesses considerable mineral wealth. In ancient times gold and precious stones were mined in the Red sea hills. Efforts were made to re-establish the industry at the be ginning of this century, but they have not been encouraging. Manganese, however, has been mined in increasing quantities dur ing the last ten years, and its output in 1926 rose to over 120,000 metric tons. Another new industry is petroleum, for which pros pecting is active: but the production of 1926 was only 173,000 tons. The salt obtained from Lake Mareotis supplies the salt needed for the country, except a small quantity used for curing fish at Lake Menzala; while the lakes in the Wadi Natron, 45 m. N.W. of the pyramids of Giza, furnish carbonate of soda in large quantities. Alum is found in the western oases. Nitrates and phosphates are also found in various parts of the desert and are used as manures. The turquoise mines of Sinai, in the Wadi Maghara, are worked regularly by the Arabs of the peninsula, who sell the stones in Suez; while there are emerald mines at Jebel Zubara, south of Kosseir. Considerable veins of haematite of good quality occur both in the Red sea hills and in Sinai. At Jebel ed-Dukhan are porphyry quarries, extensively worked under the Romans, and at Jebel el-Fatira are granite quarries. At El Hammamat, on the old way from Coptos to Philoteras Portus, are the breccia verde quarries, worked from very early times, and having interesting hieroglyphic inscriptions. The quarries of Sy ene (Aswan) are famous for extremely hard and durable red gran ite (syenite), and have been worked since the days of the earliest Pharaohs. Large quantities of this syenite were used in building the Aswan dam (1898-1902). The cliffs bordering the Nile are largely quarried for limestone and sandstone.

Climate.

Part of Upper Egypt is within the tropics, but the greater part of the country is north of the Tropic of Cancer. Except a narrow belt along the Mediterranean shore, Egypt lies in an almost rainless area, where the temperature is high by day and sinks quickly at night in consequence of the rapid radiation under the cloudless sky. The mean temperature at Alexandria and Port Said varies between 57° F in January and 81° F in July; while at Cairo, where the proximity of the desert begins to be felt, it is 53° F in January, rising to 84° F in July. January is the coldest month, when occasionally in the Nile valley, and more frequently in the open desert, the temperature sinks to 32° F, or even a degree or two below. The mean maximum temperatures are 99° F for Alexandria and 11o° F for Cairo. Farther south the range of temperature becomes greater as pure desert conditions are reached. Thus at Aswan the mean maximum is 118° F, the mean minimum 42° F.The relative humidity varies greatly. At Aswan the mean value for the year is only 38%, that for the summer being 29%, and for the winter 51%; at Cairo the corresponding figures are about 45% and 70%. A white fog, dense and cold, sometimes rises from the Nile in the morning, but it is of short duration and rare occurrence. In Alexandria and on all the Mediterranean coast of Egypt rain falls abundantly in the winter months, from 8 to 12 in. in the year; but southwards it rapidly decreases, and south of 31° N. little rain falls.

Records at Cairo show that the rainfall is very irregular, and is furnished by occasional storms rather than by any regular rainy season ; still, it is growing more frequent and approximates 2 in. in the year. In the open desert rain falls even more rarely, but it is by no means unknown, and from time to time heavy storms burst, causing sudden floods in the narrow ravines, and drowning both men and animals. Snow is unknown in the Nile valley, but on the mountains of Sinai and the Red sea hills it is not uncom mon, and a temperature of 18° F at an altitude of 2,000 ft. has been recorded in January.

The atmospheric pressure, with a mean of just under 3o in., varies between a maximum in January and a minimum in July, the mean difference being about 0.29 in.

The most striking meteorological factor in Egypt is the per sistence of the north wind throughout the year, without which the climate would be very trying. At Cairo, in the winter months, south and west winds are frequent ; but after this the north blows almost continuously for the rest of the year. Farther south the southern winter winds decrease rapidly, becoming westerly, until at Aswan and Wadi Halfa the northerly winds are almost in variable throughout the year. The khamsin, hot sand-laden winds of the spring months, come invariably from the south. They are preceded by a rapid fall of the barometer for about a day, when the wind starts in a southerly quarter, and drops about sunset. The same thing is repeated on the second and sometimes the third day, by which time the wind has worked round to the north again. During a khamsin the temperature is high and the air extremely dry, while the dust and sand carried by the wind form a thick yellow fog obscuring the sun. Another remarkable phe nomenon is the zobaa, a lofty whirlwind of sand resembling a pillar, which moves with great velocity.

One of the most interesting phenomena of Egypt is the mirage, which is frequently seen both in the desert and in the waste tracts of uncultivated land near the Mediterranean ; and it is often so truthful in its appearance that one finds it difficult to admit the illusion.

Flora.

Egypt possesses neither forests nor woods and, as practically the whole of the country which will support vegeta tion is devoted to agriculture, the flora is limited. The most im portant tree is the date-palm, which grows all over Egypt and in the oases. The dom-palm is first seen a little north of 26° N., and extends southwards. The vine grows well, and in ancient times was largely cultivated for wine ; oranges, lemons and pomegran ates also abound. Mulberry trees are common in Lower Egypt. The sunt tree (Acacia nilotica) grows everywhere, as well as the tamarisk and the sycamore. In the deserts halfa grass and several kinds of thorn bushes grow; and wherever rain or springs have moistened the ground, numerous wildflowers thrive. This is es pecially the case where there is also shade to protect them from the midday sun, as in some of the narrow ravines in the eastern desert and in the palm groves of the oases, where various ferns and flowers grow luxuriantly round the springs. Among many trees which have been imported, the "lebbek" (Albizzia lebbek), a thick-foliaged mimosa, thrives especially, and has been very largely employed. The weeping-willow, myrtle, elm, cypress and eucalyptus are also used in the gardens and plantations.The most common of the fruits are dates, of which there are nearly 3o varieties, which are sold half-ripe, ripe, dried, and pressed in their fresh moist state in mats or skins. The pressed dates of Siwa are among the most esteemed. The Fayum is cele brated for its grapes, and chiefly supplies the market of Cairo. The best-known fruits, besides dates and grapes, are figs, sycamore figs and pomegranates, apricots and peaches, oranges and citrons, lemons and limes, bananas, different kinds of melons (including some of aromatic flavour, and the refreshing water-melon), mul berries, Indian figs or prickly pears, the fruit of the lotus and olives. Among the more usual cultivated flowers are the rose (which has ever been a favourite among the Arabs), the jasmine, narcissus, lily, oleander, chrysanthemum, convolvulus, geranium, dahlia, basil, the henna plant (Lawsonia alba, or Egyptian privet), the helianthus and the violet. Of wild flowers the most common are yellow daisies, poppies, irises, asphodels and ranunculuses. The Poinsettia pulcherrima is a bushy tree with leaves of brilliant red.

Many kinds of reeds are found in Egypt, though they were formerly much more common. The famous byblus or papyrus no longer exists in the country, but other kinds of cyperi are found. The lotus, greatly prized for its flowers by the ancient inhabitants, is still found in the Delta, though never in the Nile itself.

Fauna.—The chief quadrupeds are all domestic animals. Of these the camel and the ass are the most common. The ass, often a tall and handsome creature, is indigenous. When the camel was first introduced into Egypt is uncertain—it is not pictured on the ancient monuments. Neither is the buffalo, which with the sheep is very numerous in Egypt. The horses are of indifferent breed, apparently of a type much inferior to that possessed by the ancient Egyptians. Wild animals are few. The principal are the hyena, jackal and fox. The wild boar is found in the Delta. Wolves are rare. Numerous gazelles inhabit the deserts. The ibex is found in the Sinaitic peninsula and the hills between the Nile and the Red sea, and the mouflon, or maned sheep, is occa sionally seen in the same regions. The desert hare is abundant in parts of the Fayum, and a wild cat, or lynx, frequents the marshy regions of the Delta. The ichneumon (Pharaoh's rat) is common and often tame; the coney and jerboa are found in the eastern mountains. Bats are very numerous. The crocodile is no longer found in Egypt, nor the hippopotamus, in ancient days a fre quenter of the Nile. Among reptiles are several kinds of venomous snakes—the horned viper, the hooded snake and the echis. Lizards of many kinds are found, including the monitor. There are many varieties of beetle, including a number of species representing the scarabaeus of the ancients. Locusts are comparatively rare. The scorpion, whose sting is sometimes fatal, is common. There are many large and poisonous spiders and flies ; fleas and mosquitoes abound. Fish are plentiful in the Nile, both scaled and without scales. The scaly fish include members of the carp and perch kind, and over too species have been classified.

Some 30o species of birds are found in Egypt, and one of the most striking features of a journey up the Nile is the abundance of bird life. Birds of prey are very numerous, including several varieties of eagles—the osprey, the spotted, the golden and the imperial. Of vultures the black and white Egyptian variety (Neo phron percnopterus) is most common. The griffon and the black vulture are also frequently seen. There are many kinds of kites, falcons and hawks, kestrel being numerous. The long-legged buz zard is found throughout Egypt, as are owls. The so-called Egyp tian eagle owl (Bubo ascalaphus) is rather rare, but the barn owl is common. The kingfisher is found beside every water-course, a black and white species (Ceryle rudis) being much more nu merous than the common kingfisher. Pigeons and hoopoes abound in every village. There are various kinds of plovers—the black headed species (Pluvianus aegyptius) is most numerous in Upper Egypt ; the golden plover and the white-tailed species are found chiefly in the Delta. The spurwing is supposed to be the bird mentioned by Herodotus as eating the parasites covering the in side of the mouth of the crocodile. Of game-birds the most plen tiful are sandgrouse, quail (a bird of passage) and snipe. Red legged and other partridges are found in the eastern desert and the Sinai hills. Of aquatic birds there is a great variety. Three species of pelican exist, including the large Dalmatian pelican. Storks, cranes, herons and spoonbills are common. The sacred ibis is not found in Egypt, but the buff-backed heron, the constant companion of the buffalo, is usually called an ibis. The glossy ibis is occasionally seen. The flamingo, common in the lakes of Lower Egypt, is not found on the Nile. Geese, duck and teal are abundant. The most common goose is the white-fronted variety; the Egyptian goose is more rare. Several birds of gorgeous plu mage come north into Egypt in spring, such as the golden oriole, the sun-bird, the roller and the blue-cheeked bee-eater.

Few countries have suffered more, reckoned in terms of human life, from misgovernment, and few countries have recov ered more promptly under humane administration, than Egypt. In 1800 the French estimated the population at no more than 2,460,000. At the beginning of British occupation (census of 1882) it was 6,813,919. In 1917, after 35 years of the British connection, the figure had risen to 12,750,918; and the census held in 1927 put it at 14,168,756. The result is a wholly abnormal density of population on the soil: if the desert regions be ex cluded, it is over I,000 per sq.m., far in excess of Belgium or of Bengal.

Of the total population, about 2o% is urban. In addition to pure nomads, there are half-a-million Bedouins described as "semi sedentaries," i.e., tent-dwelling Arabs, usually encamped in those parts of the desert adjoining the cultivated land. The rural classes are mainly engaged in agriculture, which occupies over 62% of the adults. The professional and trading classes form about 1o% of the whole population, but so% of the foreigners are engaged in trade.

Chief Towns.

Cairo, the capital and the largest city in Africa, stands on the Nile, at the head of the Delta, and has been called by the Arabs "the diamond stud in the handle of the fan of Egypt." Next in importance of the cities of Egypt and the chief seaport is Alexandria, on the shore of the Mediterranean at the western end of the Delta. Port Said, at the eastern end of the Delta, and at the north entrance to the Suez canal, is the second seaport. Between Alexandria and Port Said are the towns of Rosetta and Damietta, each built a few miles above the mouth of the branch of the Nile of the same name. The other ports of Egypt are Suez at the south entrance of the canal, Kosseir on the Red sea, the seat of the trade carried on between Upper Egypt and Arabia, Mersa Matruh, near the Tripolitan frontier, and El-Arish, on the Mediterranean, near the frontier of Palestine, and a halting-place on the caravan route from Egypt to Syria. In the interior of the Delta are many flourishing towns, the largest being Tanta, Damanhur, Mansura, Zagazig and Belbes. Ismailia is situated midway on the Suez canal. All these towns, which depend largely on the cotton industry, are separately noticed.Other towns in Lower Egypt are : Mehallet el-Kubra, with manufactories of silk and cottons; Salihia on the edge of the des ert south of Lake Menzala, and the starting-point of the caravans to Syria; Mataria on Lake Menzala and headquarters of the fish ing industry; Zifta on the Damietta branch and the site of a barrage; Samanud, also on the Damietta branch, noted for its pottery, and Fua where large quantities of tarbushes are made, on the Rosetta branch. Shibin el-Kom is a cotton centre, and Menuf in the fork between the branches of the Nile, is the chief town of a rich agricultural district. There are many other towns in the Delta with populations between 1o,000 and 20,000.

In Upper Egypt the chief towns are nearly all in the narrow val ley of the Nile, except Medinet-el-Fayum, the capital of that oasis, with a pop. of 40,000. The chief towns on the Nile, taking them in their order in ascending the river from Cairo, are Beni Suef, Minia, Assiut, Akhmim, Suhag, Girga, Kena, Luxor, Esna, Edfu, Assuan and Korosko. Beni Suef, 77 m. from Cairo by rail, is the capital of a mudiria and a centre for the manufacture of woollen goods. Minia, 77 m. by rail farther south is also the capital of a mudiria, has a considerable European colony, possesses a large sugar factory and some cotton mills. Assiut, 235 m. S. of Cairo by rail, is the most important commercial centre in Upper Egypt. At this point a barrage is built across the river. Suhag, 56 m. by rail S. of Assiut, is the headquarters of Girga mudiria and has two ancient and celebrated Coptic monasteries in its vicinity. A few miles above Suhag, on the opposite (east) side of the Nile is Akhmim, where silk and cotton goods are made. Girga, 22 M. S. by rail of Suhag, is noted for its pottery. Kena, on the east bank of the Nile, 145 m. by rail from Assiut, is the chief seat of the manufacture of the porous earthenware water-bottles used all over Egypt. Luxor, 418 m. from Cairo, marks the site of Thebes. Esna is another place where pottery is made in large quantities. It is on the west bank of the Nile, 36 m. by rail south of Luxor; and Edfu, 3o m. farther south, is chiefly famous for its ancient temple. Aswan is at the foot of the First Cataract and 551 m. S. of Cairo by rail. Three miles farther south, at Shellal, the Egyp tian railway terminates. Korosko, 118 m. by river above Aswan, was the northern terminus of the old caravan route from the Sudan across the Nubian desert.

Ancient Cities and Monuments.

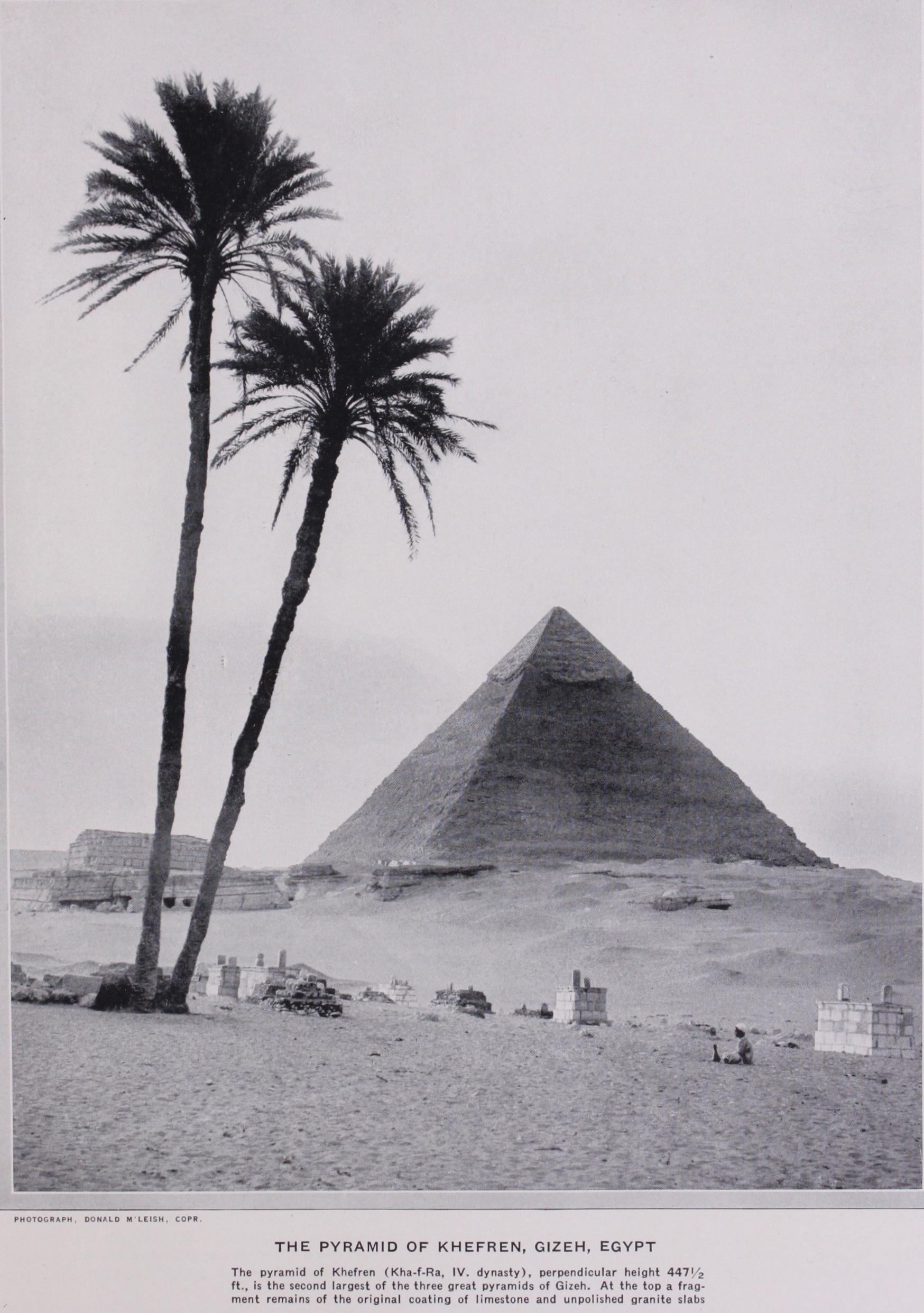

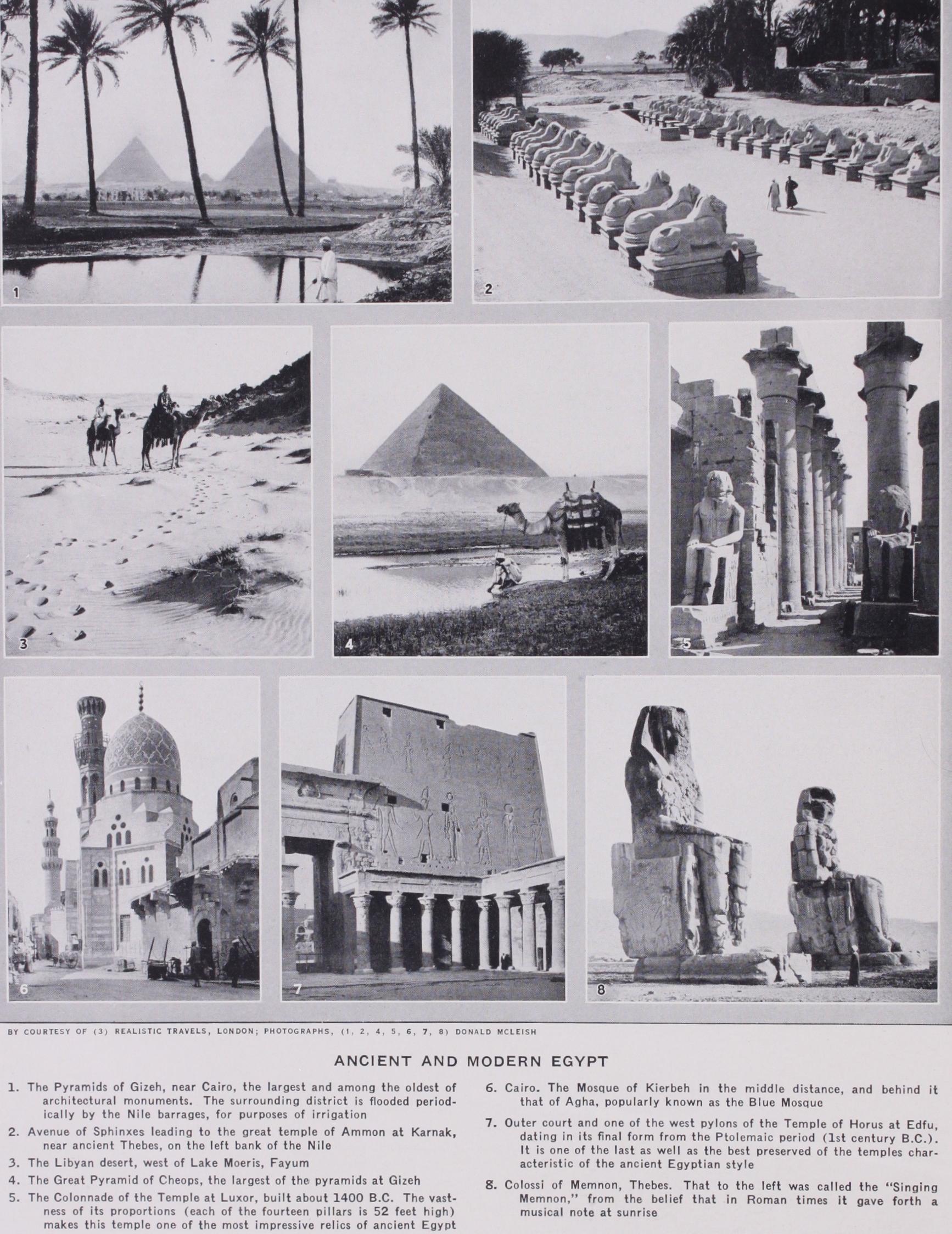

To many visitors the re mains of Egypt's remote past are of deeper interest than the ac tivities of her modern cities. They will find the present and the past closely mingled: for the larger towns of to-day are, in many cases, built on the sites of ancient cities, and they generally con tain some monuments of the time of the Pharaohs, Greeks or Romans. The sites of other ancient cities now in complete ruin may be indicated. Memphis, the Pharaonic capital, was on the wept bank of the Nile, some 14 m. above Cairo, and Heliopolis lay some 5 m. N.N.E. of Cairo. The pyramids of Giza or Gizeh, on the edge of the desert, 8 m. W. of Cairo, are the largest of the many pyramids and other monuments, including the famous Sphinx, built in the neighbourhood of Memphis. Thebes has been replaced in part by Luxor. Syene stood near to where the town of Aswan now is ; opposite, on an island in the Nile, are scanty ruins of the city of Elephantine, and a little above, on another island, is the temple of Philae. The ancient Coptos (Kett) is rep resented by the village of Kuft, between Luxor and Kena. A few miles north of Kena is Dendera, with a famous temple. The ruins of Abydos, one of the oldest places in Egypt, are 8 m. S.W. of Balliana, a small town in Girga mudiria. The ruined temples of Abu Simbel are on the west side of the Nile, 56 m. above Korosko. On the Red sea, south of Kosseir, are the ruins of Myos Hormos and Berenice. Of the ancient cities in the Delta there are remains, among others, of Sais, Iseum, Tanis, Bubastis, Onion, Sebennytus, Pithom, Pelusium, and of the Greek cities Naucratis and Daph nae. There are, besides the more ancient cities and monuments, a number of Coptic towns, monasteries and churches in almost every part of Egypt, dating from the early centuries of Christianity. The monasteries, or ders, are generally fort-like buildings and are often built in the desert. Tombs of Mohammedan saints are also numerous, and are often placed on the summit of the cliffs over looking the Nile. The traveller in Egypt thus views, side by side with the activities of the present day, memorials of every race and civilization which has flourished in the valley of the Nile.

Races and Religion.

The population is generally divisible into (I) the f ellahin or peasantry, and the townsmen of the same blood : Mohammedans and Copts far predominating in both cases; (2) the Bedouins, or nomad Arabs of the desert, comprising the Arabic-speaking tribes who range as far south as 26° N., and the racially distinct tribes (Hadendowa, Aisharin, Abanda, etc.) in habiting the desert from Kosseir to Suakin: (3) the Nuba Nubians or Berberin, who occupy the Nile valley between Aswan and Don gola : they are mainly agriculturists, though they take kindly to trading, and seem to be chiefly of mixed negro and Arab blood; and (4) foreigners, over 150,000 in number, and chiefly Greeks, whose great centre is Alexandria—Italians, British and French. Syrians and Levantines abound, and there is a Persian colony. The Turkish element is only a few thousand strong, but holds a high social position.The great majority of the people are Mohammedans 000 out of 12, 718,000 in 1917) . Christians in 1917 numbered 1,026,000, composed mainly of Copts (857,000), with an admix ture of Armenian, Syrian and Maronite sects, Roman Catholics (Io8,000) and a variety of Protestant bodies (47,000). There were 6o,000 Jews at the same census.

The Mohammedans are Sunnites, principally of the persuasion of the Sha fi'is, whose celebrated founder, the imam ash-Shafi'i, is buried in the great southern cemetery of Cairo. Many of them are, however, Hanifis (to which persuasion the Turks chiefly be long), and in parts of Lower, and almost universally in Upper, Egypt, Malikis. Among the Muslims the Sheikh-el-Islam, ap pointed by the khedive from among the Ulema (learned class), exercises the highest religious and, in certain subjects, judicial authority. Valuable property is held by the Mohammedans in trust for the promotion of religion and for charitable purposes, and is known as the Wakfs administration. The revenue derived is over £250,000 yearly.

The Coptic organization is ruled by the Patriarch of Alexandria, whose jurisdiction extends over Ethiopia also, and who is assisted by three metropolitans and twelve bishops.

Manners and Customs.

In physique the Egyptians are of full average height (the men are mostly 5 ft. 8 in. or 5 ft. 9 in.) , and both sexes are remarkably well proportioned and strong. The Cairenes and the inhabitants of Lower Egypt generally have a clear complexion and soft skin of a light yellowish colour; those of Middle Egypt have a tawny skin, and the dwellers in Upper Egypt a deep bronze or brown complexion. The face of the men is of a fine oval, forehead prominent but seldom high, straight nose, eyes deep set, black and brilliant, mouth well formed, but with rather full lips, regular teeth beautifully made, and beard usually black and curly but scanty. Moustaches are worn, while the head is shaved save for a small tuft (called shushe/i) upon the crown. As to the women, "from the age of about 14 to that of 18 or 20, they are generally models of beauty in body and limbs; and in countenance most of them are pleasing, and many exceed ingly lovely; but soon after they have attained their perfect growth, they rapidly decline." Tattooing is common with both sexes, and the women stain their hands and feet with henna.Dress is being materially altered, at least in urban society, by the growing adoption of European clothing, and by the emancipa tion of women from a seclusion which was symbolized in the obscuring character of their outdoor raiment. Among the men of the upper and middle classes who retain their old practice, the ordinary dress consists of cotton drawers, and a cotton or silk shirt with very wide sleeves. Above these are generally worn a waistcoat without sleeves, and a long vest of silk, called kaftan, which has hanging sleeves, and reaches nearly to the ankles. The kaftan is confined by the girdle, which is a silk scarf, or cashmere or other woollen shawl. Over all is worn a long cloth robe, the gibbeh (or jibbeh) somewhat resembling the kaftan in shape, but having shorter sleeves, and being open in front. The dress of the lower orders is the shirt and drawers, and waistcoat, with an outer shirt of blue cotton or brown woollen stuff ; some wear a kaftan. The head-dress is the red cloth fez or tarbush round which a turban is usually worn. Men who have otherwise adopted Euro pean costume retain the tarbush. The fellahin wear nothing but drawers and a long blue gown of linen or cotton, with a belt, and in cold weather a coarse brown cloak over all. Many professions and religions, etc., are distinguished by the shape and colour of the turban, and various classes, and particularly servants, are marked by the form and colour of their shoes; but the poor go usually barefoot. An increasing number of ladies of the upper classes now dress in European style, with certain modifications, such as the head-veil, though its use is now being largely aban doned in the cities. Those who retain native costume wear a very full pair of silk trousers, bright coloured stockings (usually pink), and a close-fitting vest with hanging sleeves and skirts, open down the front and at the sides, and long enough to turn up and fasten into the girdle, which is generally a cashmere shawl; a cloth jacket, richly embroidered with gold, and having short sleeves, is com monly worn over the vest. The women of the lower orders have trousers of printed or dyed cotton, and a close waistcoat. All wear the long and elegant head-veil. This is a simple "breadth" of muslin, which passes over the head and hangs down behind, one side being drawn forward over the face in the presence of a man. A lady's veil is of white muslin, embroidered at the ends in gold and colours ; that of a person of the lower class is simply dyed blue. It is intended to conceal all the features save the eyes. Ladies use slippers of yellow morocco, and abroad, inner boots of the same material, above which they wear, in either case, thick shoes, having only toes. The poor wear red shoes, very like those of the men. The women, especially in Upper Egypt, not infre quently wear nose-rings.

The principal meals are breakfast, about an hour after sunrise; dinner, or the mid-day meal, at noon; and supper, which is the chief meal of the day, a little after sunset. Pastry, sweetmeats and fruit are highly esteemed. Coffee is taken at all hours, and is, with a pipe, presented at least once to each guest. Tobacco is the great luxury of the men of all classes in Egypt, who begin and end the day with it, and generally smoke all day with little inter mission. Many women, also, especially among the rich, adopt the habit.

In social intercourse the Egyptians observe many forms of salutation and much etiquette ; they are very affable, and readily enter into conversation with strangers. Their courtesy and dig nity of manner are striking, and are combined with ease and a fluency of discourse. They have a remarkable quickness of appre hension, a ready wit and a retentive memory. They are fatalists, and bear calamities with surprising resignation. Filial piety, re spect for the aged, benevolence and charity are conspicuous in their character. Humanity to animals is another virtue, and cruelty is openly discountenanced in the streets. Their cheerful ness and hospitality are remarkable, as well as frugality and tem perance in food and drink, and honesty in the payment of debt. Their cupidity is mitigated by generosity ; their natural indolence by the necessity, especially among the peasantry, to work hard to gain a livelihood.

The amusements of the people are generally not of a violent kind, being in keeping with their sedentary habits and the heat of the climate. The bath is a favourite resort of both sexes and all classes. Notwithstanding its condemnation by Mohammed, music is the most favourite recreation of the people ; the songs of the boatmen, the religious chants, and the cries in the streets are all musical. There are male and female musical performers ; the former are both instrumental and vocal, the latter (called `Almeh, pl. `Awalim) generally vocal. The `Awalim are, as their name ("learned") implies, generally accomplished women, and should not be confounded with the Ghawazi, or dancing-girls. There are many kinds of musical instruments. The music, vocal and instru mental, is generally of little compass, and in the minor key; it is therefore plaintive, and strikes a European ear as somewhat monotonous, though often possessing a simple beauty, and the charm of antiquity, for there is little doubt that the favourite airs have been handed down from remote ages. Many of the dancing girls of Cairo to-day are neither `Awalim nor Ghawazi, but women of the very lowest class whose performances are both ungraceful and indecent. A most objectionable class of male dancers also ex ists, who imitate the dances of the Ghawazi, and dress in a kind of nondescript female attire. Not the least curious of the public per formances are those of the serpent-charmers, who are generally Rifa`ia (Saadia) dervishes. Their power over serpents has been doubted, yet their performances remain unexplained; they, how ever, always extract the fangs of venomous serpents. Jugglers, rope-dancers and farce-players must also be mentioned. In the principal coffee-shops of Cairo are to be found reciters of ro mances, surrounded by interested audiences.

The first ten days of the Mohammedan year are held to be blessed, and especially the tenth. On the tenth day, being the an niversary of the martyrdom of Hosain, the son of Ali and grand son of the Prophet, the mosque of the Hasanen at Cairo is thronged to excess, mostly by women. In the evening a procession goes to the mosque, the principal figure being a white horse with white trappings, upon which is seated a small boy, the horse and the lad, who represents Hosain, being smeared with blood. From the mosque the procession goes to a private house, where a mullah recites the story of the martyrdom. Following the order of the lunar year, the next festival is that of the Return of the Pilgrims, which is the occasion of great rejoicing, many having friends or relatives in the caravan. The Mahmal, a kind of covered litter, first originated by Queen Sheger-ed-Dur, is brought into the city in procession, though not with as much pomp as when it leaves with the pilgrims. The Birth of the Prophet (Molid en-Nebi), which is celebrated in the beginning of the third month, is the greatest festival of the whole year. For nine days and nights Cairo has more the aspect of a fair than of a city keeping a religious festival. The chief ceremonies take place in some large open spot round which are erected the tents of the khedive, of great State officials, and of the dervishes. Next in time, and also in impor tance, is the Molid El-Hasanen, commemorative of the birth of Hosain, and lasting 15 days and nights; and at the same time is kept the Molid of al-Salih Ayyub, the last sovereign but two of the Ayyubite dynasty. In the seventh month occur the Molid of the sayyida Zenab, and the commemoration of the Miarag, or the Prophet's miraculous journey to heaven. Early in the eighth month (Sha`ban), the Molid of the imam Shafi`i is observed; and the night of the middle of that month has its peculiar customs, being held by the Mohammedans to be that on which the fate of all living is decided for the ensuing year. Then follows Ramadan, the month of abstinence, a severe trial to the faithful; and the Lesser Festival (Al-'id as-saghir), which commences the new month of Shawwal, is hailed by them with delight. A few days after, the Kiswa, or new covering for the Ka`ba at Mecca, is taken in procession from the citadel, where it is always manu factured, to the mosque of the Hasanen to be completed ; and, later, the caravan of pilgrims departs, when the grand procession of the Mahmal takes place. On the tenth day of the last month of the year the Great Festival (Al-'id al-kabir), or that of the Sacrifice (commemorating the willingness of Ibrahim to slay his son Ismail), closes the calendar. The Lesser and Great Festivals are those known in Turkish as the Bairam (q.v.).

The rise of the Nile is naturally the occasion of annual customs, some of which are doubtless relics of antiquity; these are observed according to the Coptic calendar. The commencement of the rise is commemorated on the night of the i rth of Bauna, June 17, called that of the Drop (Lelet-en-Nukta), because a miraculous drop is then supposed to fall and cause the swelling of the river. The real rise begins at Cairo about the summer solstice, or a few days later, and early in July a crier in each district of the city begins to go his daily rounds, announcing, in a quaint chant, the increase of water in the nilometer of the island of Roda. When the river has risen 20 or 21 ft., he proclaims the Wefa en-Nil, "Completion" or "Abundance of the Nile." The crier continues his daily rounds, with his former chant, excepting on the Coptic New Year's Day, when the cry of the Wef a is repeated, until the Salib, or Discovery of the Cross, Sept. 26 or 27, at which period, the river having attained its greatest height, he concludes his annual employment with another chant, and presents to each house some limes and other fruit, and dry lumps of Nile mud.

Tombs of saints abound, one or more being found in every town and village; and no traveller up the Nile can fail to remark how every prominent hill has the sepulchre of its patron saint. The great saints of Egypt are the imam Ash-Shafi`i, founder of the persuasion called after him, the sayyid Ahmad al-Baidawi, and the sayyid Ibrahim ed-Desuki, both of whom were founders of orders of dervishes. Egypt holds also the graves of several members of the Prophet's family, the tomb of the sayyida Zeyneb, daughter of `Ali, that of the sayyida Sekeina, daughter of Hosain, and that of the sayyida Nefisa, great-granddaughter of Hasan, all of which are held in high veneration. The mosque of the Hasanen (or that of the "two Hasans") is the most reverenced shrine in the country, and is believed to contain the head of Hosain. Many orders of Dervishes live in Egypt, all presided over by a direct descendant of the caliph Abu Bekr, called the Sheikh el-Bekri. The Saadia are famous for charming and eating live serpents, etc., and the `Ilwania for eating fire, glass, etc. The Egyptians firmly believe in the efficacy of charms, a belief associated with that in an omnipresent and over-ruling providence. Thus the doors of houses are inscribed with sentences from the Koran, or the like, to preserve from the evil eye, or avert the dangers of an unlucky threshold ; similar inscriptions may be observed over most shops, while almost every one carries some charm about his person. The so-called sciences of magic, astrology and alchemy still flourish.

The national flag of Egypt is green, and has a white crescent enclosing three five-pointed white stars between its horns.

Constitution and

until the World War, was nominally a tributary State of the Turkish empire, ruled by a khedive appointed by the sultan. The steps by which it passed into an independent State, under a hereditary monarch with the title of king (now Fuad I.) are shown in detail under the section History. The exact measure of Egypt's independence remains unsettled so long as no agreement is reached on the points re served in the unilateral declaration by which Great Britain recog nized Egypt as a sovereign State. Equally unsettled is the dis tribution of constitutional power within the country. In theory, the central administration is carried on by a cabinet of ministers appointed by the king, and supplemented for consultative pur poses by two British advisers in matters of finance and justice. By the Constitution of 1923 legislative power is exercised by the king in concurrence with the parliament : but in 1928 the king by edict dissolved parliament and forbade it from assembling again for three years ; the former system of legislation by royal rescript being thus reverted to. The parliament, when it functions, consists of two houses, a senate, of which two-fifths of the mem bers are nominated, and a chamber of deputies, elected on the basis of one member for every 6o,000 inhabitants.For purposes of local government the chief towns constitute governorships (moa f zas), the rest of the country being divided into mudirias or provinces. The governors and mudirs (heads of provinces) are responsible to the ministry of the interior. The provinces are further divided into districts, each of which is un der a mamur, who in his turn supervises and controls the ornda, mayor or head-man, of each village in his district.

The governorships are: Cairo; Alexandria, which includes an area of 7o sq.m. ; Suez canal, including Port Said and Ismailia; Suez and El-Arish ; the Western desert ; the Southern desert ; Sinai ; and the Red sea coast. Lower Egypt is divided into the provinces of : Behera, Gharbia, Menufia, Dakahlia, Kaliubia, Sharkia. The oasis of Siwa and the country to the Tripolitan frontier are dependent on the province of Behera. The provinces of Upper Egypt are : Giza, Beni Suef, Fayum, Minia, Assiut, Girga, Kena, Aswan. The peninsula of Sinai is administered by the War Office.

Justice.—There are four judicial systems in Egypt : two ap plicable to Egyptian subjects only, one applicable to foreigners only, and one applicable to foreigners and, to a certain extent, Egyptians, also. This multiplicity of tribunals arises from the fact that, owing to the Capitulations, which apply to Egypt as having belonged to the Turkish empire, foreigners are almost entirely exempt from the jurisdiction of the native courts. It will be convenient to state first the law under the old regime as regards foreigners, and secondly the law which concerns Egyp tians; though it will be understood that the position regarding the Capitulations is in a state of flux, with the movement of Egypt towards independence. Criminal jurisdiction over foreigners is exercised by the consuls of those Powers possessing such right by treaty, according to the law of the country of the offender. These consular courts also judge civil cases between foreigners of the same nationality.

Jurisdiction in civil matters between Egyptians and foreigners and between foreigners of different nationalities is no longer ex ercised by the consular courts. The grave abuse to which the consular system was subject led to the establishment, in Feb. 1876, at the instance of Nubar Pasha and after eight years of negotiation, of International or "Mixed" Tribunals to supersede consular jurisdiction to the extent indicated. The Mixed Tribunals, composed of both foreign and Egyptian judges, employ a code based on the Code Napoleon with such additions from Moham medan law as are applicable. In certain designated matters they enjoy criminal jurisdiction, including, since 1900, offences against the bankruptcy laws. Cases have to be conducted in Arabic, French, Italian or English. Besides their judicial duties, the courts practically exercise legislative functions, as no important law can be made applicable to Europeans without the consent of the powers, and the powers are mainly guided by the opinions of the judges of the Mixed Courts.

The judicial systems applicable solely to Egyptians are su pervised by the Ministry of Justice, to which has been attached since 1890 a British judicial adviser. Two systems of laws are administered :—(1) the Mehkemehs, (2) the Native Tribunals.

The mehkeme/is, or courts of the cadis, judge in all matters of personal status, such as marriage, inheritance and guardianship, and are guided in their decisions by the code of laws founded on the Koran. The grand cadi, who must belong to the sect of the Hanifis, sits at Cairo, and is aided by a council of Ulema or learned men. This council consists of the sheikh or religious chief of each of the four orthodox sects, the sheikh of the mosque of Azhar, who is of the sect of the Shafi`is, the chief (nakib) of the Sheri f s, or descendants of Mohammed, and others. The cadis are chosen from among the students at the Azhar university. (In the same manner, in matters of personal law, Copts and other non-Mohammedan Egyptians are, in general, subject to the juris diction of their own religious chiefs.) For other than the purposes indicated, the old indigenous judi cial system, both civil and criminal, was superseded in 1884 by tribunals administering a jurisprudence modelled on that of the French code. The system was, on the advice of an Anglo-Indian official (Sir John Scott), modified and simplified in 1891, but its essential character remained unaltered. In 1904, however, more important modifications were introduced. Save on points of law, the right of appeal in criminal cases was abolished, and assize courts, whose judgments were final, established. At the same time the penal code was thoroughly revised, so that the Egyptian judges were "for the first time provided with a sound working code." There are courts of summary jurisdiction presided over by one judge, central tribunals (or courts of first instance) with three judges, and a court of appeal at Cairo. A committee of judicial surveillance watches the working of the courts of first instance and the summary courts, and endeavours, by letters and discussions, to maintain purity and sound law. There is a pro cureur-general, who, with other duties, is entrusted with criminal prosecutions. His representatives are attached to each tribunal, and form the parquet under whose orders the police act in bring ing criminals to justice. In the markak (district) tribunals, cre ated in 1904 and presided over by magistrates with jurisdiction in cases of misdemeanour, the prosecution is, however, conducted directly by the police. Special children's courts have been estab lished for the trial of juvenile offenders.

The police service is under the orders of the Ministry of the Interior, though the provincial police are largely under the direc tion of the local authorities, the mudirs or governors of provinces, and the mamurs or district officials ; to the omdas, or village head men, who are responsible for the good order of the villages, a limited criminal jurisdiction has been entrusted.

Education.

Two different systems of education exist, one founded on indigenous lines, the other European in character. Both systems are more or less fully controlled by the ministry of public instruction. The Government has primary, secondary and technical schools, training colleges for teachers, and colleges of commerce, education, agriculture, engineering, law, medicine and veterinary science. The Government system, which dates back to a period before the British occupation, is designed to provide, in the main, a European education. In the primary schools Arabic is the medium of instruction, the use of English for that purpose being confined to lessons in that language itself. The school of law is divided into English and French sections according to the language in which the students study law. Besides the Govern ment primary and secondary schools, there are many other schools in the large towns owned by the Mohammedans, Copts, Hebrews, and by various missionary societies, and in which the education is on the same lines. A movement initiated among the leading Mohammedans led in 1908 to the establishment as a private en terprise of a national Egyptian university devoted to scientific, literary and philosophical studies.The indigenous system of education culminates in the university mosque of el-Azhar, the largest and most important of seven well endowed Mohammedan institutions which provide instruction on traditional religious lines. El-Azhar is regarded as the chief centre of learning in the Mohammedan world. Its subjects of study are mainly the theology of Islam and the complete science of religious, moral, civil and criminal law as founded on the Koran and the traditions of the Prophet and his successors; but they also include Arabic literature and grammar, rhetoric, logic, versi fication, and a certain amount of mathematics and physical science. Attempts to reform the direction and curriculum have been uni formly defeated: and of late the el-Azhar has declared itself an organ of advanced nationalism. Its students come from all parts of the Mohammedan world ; they pay no fees, and the professors receive no salaries, subsisting mainly by private teaching, the copying of manuscripts and the reciting of the Koran.

All over the country are scattered mosque-schools or kuttabs conducted on similar lines. Their pupils are taught to recite por tions of the Koran, and most of them learn to read and write Arabic, with a little simple arithmetic. Numbers of the kuttabs have been taken under Government control, and now provide a good elementary secular education as well as a knowledge of the Koran. Other qualified schools of a similar type receive grants in-aid, provided Arabic is taught. The number of pupils in pri vate schools under Government inspection was, in 1898, the first year of the grant-in-aid system, 7,536 ; in 20 years time it had grown to over 300,000. The Copts have over i,000 primary schools, in which the teaching of Coptic is compulsory, a few in dustrial schools, and a college for higher education. There are also special schools for the teaching of Mohammedan religious law and the instruction of sheikhs.

As elsewhere, the competing demands upon the taxpayer have restricted the funds available for purposes of national education. Until the change in 1922 of the status of the country the Govern ment's policy may be described as a general concentration upon the development and encouragement of mosque schools, and pri mary education and the maintenance of a few secondary schools in Cairo and Alexandria, intended to serve as nuclei and models for the conduct of secondary education by the local educational authorities (provincial councils), Mohammedan educational trusts and private enterprise. Since the school year 1922-23 there has been a definite move towards taking over secondary schools and direct assumption of the development of secondary education by the State.

The provision of higher and general professional education has throughout been left to the State and effected in a series of sep arate schools under various Ministries. Some of these schools, notably the School of Medicine at Qasr el Aini, have acquired more than a local reputation ; but the local demand for higher edu cation is great, and many Egyptian students go to Europe and America to obtain it.

The desirability of uniting the above institutions as faculties of a modern Egyptian university has long been under consideration, and was reported on favourably in detail by a special commission in 1921. Owing, however, largely to difficulties in securing suitable accommodation and to differences in regard to means of govern ment and methods of teaching, the realization of the project has been continuously delayed. Although these difficulties have only been partially overcome, the formal and administrative incorpora tion of the specified higher schools to constitute a university was enacted by royal decree in March 1925.

Public Health.

All the capital towns of the mudirias (provinces) have now been furnished with up-to-date water sup plies, either of filtered or of deep well-water, besides many other of the larger towns. As efficient water supplies were installed, water-carriage drainage followed, and it was found that main drainage systems had to be undertaken in order to prevent the land becoming sewage-logged. Drainage systems have now been installed in Cairo, Alexandria, Port Said, Suez and several other of the larger towns. Establishments coming under the law dealing with "etablissements insalubres, incommodes et dangereux," which corresponds roughly to the British Factory Acts, are now regis tered and are visited by special inspectors. A new "milk law," controlling the collection, distribution and sale of milk, and lay ing down standards for the fat-content, etc., has been drawn up, as well as a "pure food law." Very great progress has been made in the prevention and control of epidemic disease. Plague, both bubonic and pneumonic, has been reduced to practically negligible proportions. The whole organization for the prevention and combating of cholera epi demics has been remodelled and, although infection has fre quently been brought into the country from infected areas, cholera has been prevented from developing into epidemic form, partly owing to an excellent system of port control. Typhus and re lapsing fever have been combated on modern lines, and by means of careful delousing of patients and contacts the number of cases in the country have been enormously reduced. Systematic vacci nation with revaccination in infected areas has now reduced small pox to an almost negligible quantity.In 1918 an Anti-Malaria Commission was instituted, on which the irrigation and main drainage and public health departments are represented, and a great deal of work in draining and filling in swamping areas has already been completed in districts known to be malarial. Active campaigns have now been started against ankylostomiasis and bilharzia, and travelling hospitals and dis pensaries are at work throughout the country treating the infected peasants.

A large number of ophthalmic hospitals have been built and opened throughout the country, and there is now a permanent ophthalmic hospital in every provincial capital. The Imperial War Graves Commission have built an ophthalmic research laboratory as a memorial to the men of the Egyptian Labour Corps and Camel Transport Corps who gave their lives in the World War. A new general hospital of modern design has been opened at Damietta. Dispensaries now exist in all the markaz towns and free medical treatment is given to the poor. A new pharmacy law has been promulgated, as also a law controlling the importation and sale of stupefacient drugs. Under the new law, firms importing cocaine operate under licence, and are to all intents and purposes rationed.

A number of children's dispensaries (welfare centres) and maternity homes for the poor have been opened all over the country, though the infantile mortality is still high. Housing and town-planning are receiving increased attention and an interesting experiment in laying out a model industrial settlement may now be seen at Port Fuad, immediately opposite Port Said.

1. Archaeology and Excavation.

In Egypt archaeology has won its greatest triumphs and has developed into a science that has imparted its rules and methods of work to the archaeologists in the older fields. The reason is the preservative climate of Egypt, the absence of damp, and the certainty of fine weather, that keeps things intact which would perish elsewhere, and enables the excavator to count upon absolute security of work uninterrupted by bad climatic conditions. It is through excavation in Egypt that archaeology has developed as it has during the last fifty years. There was no real excavation in Egypt, other than the opening of tombs, till the 'fifties and 'sixties of the 19th century, when the names of Rhind and of Mariette mark the beginnings. Modern archaeological investigation begins in Egypt with Naville and Petrie when the Egypt Exploration Society began to work, in the early eighties. And it is to Petrie in succession to Rhind that the "codification" of the art of Egyptian digging, so to speak, and its assumption of a scientific character, is due. Petrie was the first, after Rhind, to insist on accurate record of all finds, however insignificant they might appear to be, for who knows what thing, apparently insignificant now, might not be regarded as enormously significant by archaeologists of the future? His systematic style of work has since been adopted in various forms by numberless disciples, imitators, adapters and critics, some of whom are much more meticulously "scientific" than their model, while others think that they can take what is good from his work while dropping what they consider unnecessary labour in recording things already known almost ad nauseam, especially if they possess no virtue other than that of being ancient. Others would strictly confine the l,usiness of recording finds to the European observers, leaving nothing even to a trained native.In the 45 years that have elapsed since the first work was done for the Egypt Exploration Fund in the Delta, the original exca vators have seen grow up a great corpus of archaeological know ledge of ancient Egyptian civilization and history that depends almost entirely on scientific excavation.

Britain, America, France, Germany and Italy have all con tributed to the list of actual excavators, while Russia, Holland, Belgium and the Scandinavian countries have also added a number of scientific students of Egyptology. And the methods and aims of Egyptian archaeology have been passed on first to the Greek and international workers in Greece (with especial brilliance of results under Evans in Crete), then Italy and the West, later to Mesopotamia and lastly to India. China still awaits scientific excavation, although Chinese Turkestan has already known it with magnificent results at the hands of Sir Aurel Stein and Dr. von Lecoq. And in Chinese Turkestan we obtain results most analogous to those gained in Egypt, owing to the resemblance of the climate of the two countries ; though one is hot and the other cold, both are phenomenally dry. The methods in use in Egypt have, with necessary modifications owing to varying local condi tions been adopted everywhere. They are the methods of common sense, of accuracy in record and in fact of the scientific conscience, without which antiquarians are still mere dilettanti. The scientific man wishes to know accurately what was ; he should have no pre conceived ideas of what ought to have been ; he should have none but an ordered enthusiasm for truth, and should have a meta phorical jug of cold water ready for all undisciplined and illiterate enthusiasms. Baseless theories about Egypt, whether dealing with the Great Pyramid, an Unlucky Mummy, or "Mummy Wheat" are unhappily very popular, and the scientific archaeolo gist often has to deal very patiently with believers in ideas of this kind, connected with prophecies, ghosts and other pseudo-religious or "occult" phenomena, with which science, which is never muzzy, "occult" or obscurantist, has no muddles which it dignifies as "mysteries," and is as hard and clear as the Greek day, has nothing to do.

We have, in fact, to investigate ancient Egypt rather with the Greek spirit of clarity and naked truth than with the Semitic spirit of enthusiastic belief in veiled mysteries, or the ancient Egyptian spirit of holy muddleheadedness which makes such an appeal nowadays.

While it is to Egyptian excavation that archaeology owes its sci entific system, it is of course not the fact that Egyptian archaeo logical science owes all its knowledge to the art of excavation.

We always had the evidence of the classical writers in Egypt, chief of them of course Herodotus, whose account of Egypt is read by none with greater pleasure and instruction than by a modern archaeologist. It is not always accurate, it is often super ficial, but as a contemporary witness it is incomparable. We had the epitomes of the work of the Egyptian priest Manetho on the dynasties of Egypt : his scheme of dynasties, garbled as the royal names have been by copyists, has survived all archaeological dis covery, has proved to fit the facts, is retained by all modern historians of ancient Egypt. We have the references of many classical writers to the "mysteries" of Egyptian religion. They may have thought that they were explaining that marvellous wel ter of conflicting beliefs satisfactorily to their contemporaries; modern writers have thought they were doing the same thing. But anybody can find in the Egyptian religion whatever he wants to find in it. To the scientific observer it seems so confused and self-contradictory as to deter him from wasting his time in trying to clear up the muddle ; he would be ploughing the sands. Only description is possible (see below).

Then in modern times the decipherment of the hieroglyphs begun by Young and Champollion in 1821, and put on the basis of firm knowledge by the latter, enabled the savants swiftly to gain a more accurate knowledge of the religion and, with the dynastic skeleton of Manetho to help, make acquaintance with the flesh and blood of history derived from the monuments of the Egyptians themselves. Wilkinson and Lepsius, and of ter them Birch and Brugsch, are the greatest names associated with the early his torical work, and Lepsius, as the result of his labour with the royal Prussian expedition to Egypt in the 'forties, was the greatest of these. Gliddon was the first to talk about the new discoveries in America in the 'thirties, and Wilkinson was the first to make the new knowledge really accessible to the educated public of Britain and the United States by his famous "Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians" (first published in 1837 and re-edited by Birch in 1878), a book which has probably made not only Egyptian archaeology, but archaeology generally, familiar to many who otherwise would never have realized its enthralling interest. Though he never excavated in the modern manner, but only probed for and dug out tombs in the Theban hillside, and probably did not observe or record with anything like the care that is considered necessary nowadays, Wilkinson may be considered the father of Egyptian archaeology, as Cham pollion was the father of Egyptian philology. And the Egyptolo gists proper, the philologists, were hard at work deciphering the hieroglyphed monuments and the hieratic papyri; Birch, Goodwin, Brugsch, de Rouge. Chabas are the greatest names. We knew a great deal before the days of scientific excavation, from the monuments above ground, in Egypt and in our museums, and the relics discovered in Theban tombs. Bonaparte's great expedi tion in 1798 with his attendant savants and the resultant publica tion of the great "Description de l'Egypte" had directed the atten tion of the world to ancient Egypt, and initiated the work that culminated in Champollion's discovery, after which a real furore set in for the collection of Egyptian monuments, the bigger the better, for European Museums. Men like Salt, Belzoni and Dro vetti collected indiscriminately, with the result that, for instance, the British Museum has been saddled with dozens of figures of the lioness-headed goddess Sekhmet (many of them in quite bad repair) from Thebes, whereas two or three good ones would have sufficed. Then the era of scientific investigation and collection begins with the expedition of the French and Tuscan Govern ments, under Champollion and Rosellini in 1827, and then came the famous Prussian expedition of Lepsius (1842) which brought back objects chosen with discrimination and studied them on the spot, and in the great Denkmifiler (r 85r )—still one of our chief sources of inscriptional material—produced the first scientific work on ancient Egypt on the grand scale. Meanwhile, Wilkinson had lived and dug his tombs at Thebes, where Rhind followed him. Then came the new regime of Mariette in 1858. Egypt ceased to be a happy hunting ground of collectors ; a Museum of Antiq uities was founded and established first at Bulaq, a suburb of Cairo, and everything found had to go there.

This exclusive policy in the 'sixties and 'seventies and the strict confinement of excavation to Mariette and the Bulaq museum, filled the galleries of the new museum with a wonderful collec tion of antiquities, especially of the Old Kingdom. But the re turn to a more liberal system after Mariette's death in 1881 and the British occupation in 1882 and the concession of the right to excavate to properly accredited museums and learned societies, such as the Egypt Exploration Fund, during the almost fifty years of its existence, has actively fostered the contemporary growth of archaeological science, has enriched museums with scientifically recorded material (hardly known before), and has proved in no way prejudicial to the national museum of Egypt, which under the two regimes of Maspero and those of de Morgan and others, has probably trebled its collections as they were left by Mariette. From Bulaq the Museum had to move to Gizeh and then to the great new building at Kasr el-Nil. It has only gained by the intro duction of international co-operation and the equitable division of finds, one half to the museum, the other to the excavator. Return to a, less liberal system, by which the museum may take what it likes, all if it likes, of what an European or American expedition finds, will inevitably react unfavourably both on the museum's progress and on archaeological progress generally. It is an ele mentary consideration that the subscribers to archaeological expeditions will cease to subscribe if they see no return for their money in their own museums.

During the last fifty years the "surface" knowledge, good as it was, the result of decades of work by great scholars, has been reinforced and completed by the knowledge derived from scien tifically-directed excavations, with the result that we now know far more of the archaeology of Ancient Egypt than of any other country, not excepting Greece and Italy. For the damper climates of Greece and Italy have not been able to preserve for us all the actual objects, even things of filmy linen, textiles, everything that men used in those remote days, the furniture and the rest, made of wood, that elsewhere perishes, the last food placed for the dead in the tomb by the mourners. Egypt preserves all intact. Where else could one find a Tutenkhamon tomb? It is said that once when a tomb was opened the modern intruders saw, im printed on the sand covering the floor, the imprints of the feet of the men who had borne the mummy to its tomb four thousand years before.

It is of course not every day that a tomb so inviolate is found. Even that of Tutenkhamon seems as a matter of fact, to have been entered by robbers who did not penetrate far into it. The tombs of all the other kings of Thebes were violated long ago, long before Greek times by the Egyptians themselves, who were as consummate hereditary tomb-robbers four thousand years ago as they are now. The tomb of Queen Hetepheres at Gizeh, discov ered recently by Reisner, is a case in point. A hieratic papyrus of the 20th Dynasty (110o B.c.) records the trial of ancient Thebans for the robbery of royal tombs even then. One can only guess the lost magnificence of a tomb of a great king like Seti I. from that which we have from the tomb of an insignificant one like Tutenkhamon, and that of the plundered private tombs from the contents of these, found intact by Schiaparelli a few years ago, which are in the Museum of Turin.

The Egyptians were not always buried in stately rock-cut tombs. Excavation has revealed one thing unknown to the older archaeologists—the whole prehistoric or pre-dynastic period, with its weapons of flint, and its crouched bodies in shallow graves. Similar groups were used long after in crowded necropoles, such as Abydos, which are much confused and difficult to dig.

Excavation by no means confines itself to tombs and graves. Temples and town-ruins are more usual subjects for excavation nowadays, and the latter especially provide much more difficult problems in excavation than tombs, or even superimposed and confused graves. The problem of stratification presents itself, and often demands the utmost skill and careful observation on the part of the excavator to unravel. This is, above all, one of the major tasks of the new archaeologist. It presents itself in greater complexity in Greece and in Syria than in Egypt, where super • imposed town-strata of succeeding periods in a tell or mound are not so common.

2. Development of Egyptian Civilization As Revealed by Archaeology: the Palaeolithic Period.—The most ancient relics of antiquity in Egypt are the palaeolithic tools of flint and chert found on the lower desert plateaux at the head of the wad's that debouch into the Nile-valley throughout its length in Egypt. These are sometimes found in their ateliers where they were origi nally knapped from the flint boulders that are common in the desert. The most usual form is that of the Acheulian coup-de poing or hand-axe. These ancient tools are often deeply patinated by the wind and sun of the ages that have elapsed since they were made. The people who used them evidently lived on the desert margin of the valley, where there was as yet no cultivation, but probably an endless marsh, inundated yearly without check by the rising Nile-flood. We have little proof of much difference in climate from that of to-day. It is not probable that the desert was then covered with humus in which grew trees favoured by a rainier climate; the fossil trees found in the desert belong to an older time when no doubt the climate was in reality different.

The Neolithic Age.—How far these palaeoliths of Egypt were contemporary with those of Northern Europe we do not know. At any rate it does not look as if there was a definite break be tween the palaeolithic and the neolithic people, who as late as the fifth millennium B.C. lived in the valley. They still used flint and chert, very rarely obsidian. The art of flint-knapping has devel oped greatly, and in a way peculiar to the Nilotes, whose flint and chert weapons are often quite different from those of the rest of the ancient world. They are often chipped with the most extraordinary care, and some knives have a serrated edge so minute as hardly to be visible to the naked eye. They are among the most beautiful of the products of the flint-knapper. The people who made them were not merely hunters, as the palaeolithic folk probably were. They were also pastoralists and, to an extent at least, agriculturalists. The regulation of the Nile flood and the rec lamation of the soil of the valley had begun. Indigenous civiliza tion began slowly to develop. The makers of the flint knives also made stone vessels with the aid of emery (which must have come from abroad, as none is known in Egypt), crude pottery and basket work. The pottery developed, on indigenous lines, like the flint working, and we have innumerable examples of it, all made with out the wheel, in the red and black polished ware, and the less common red ware with white decoration; then later the buff ware with red painted decoration representing ships with oars (rarely sails), men and women and animals, which have been recovered from the shallow graves in which the neolithic people were buried. The bodies were usually wrapped in mats and were placed in a crouching position. They were not mummified in any way, their preservation being due to the dryness of the soil in Upper Egypt ; though it is possible that they may sometimes have been smoked. This indigenous culture has been shown by the work of the Archaeological Survey of Nubia to have existed in Nubia also where a local form of it persisted so late as the time of the 12th Dynasty. We do not know how long it was before copper made its first appearance in Egypt. We have no absolute chronology of the pre-dynastic period, the age to which the neo lithic remains of course belong, and the post-neolithic antiquities up to the time of the union of the kingdom under the First Dynasty, about 3400-3200 B.C. (see CHRONOLOGY). But on purely archaeological evidence Prof. Sir Flinders Petrie has devised a scheme of "sequence dating" (q.v.) of pre-dynastic antiquities which can be used as a sort of "chronologimeter." So great a number of pre-dynastic necropoles have been excavated that we can trace in them the coming into vogue of various types of flints, pots, stone vases, etc., their period of use, and their gradual disuse, and we can say with comparative certainty that that type of flint and that of vase were in use together, and no other. So at Sequence-date (s.n.) 5o we can say that such-and-such things were in use, and none other. And as we take r-1oo as our gamut, and leave say 1-3o at the beginning for unknown beginnings and say 8o–ioo at the end of the period for the transition to dynastic styles, we see that S.D. 50 is about the middle of the dynastic period. What actual date S.D. 5o corresponds to of course we do not know. We think that the first Dynasty began not before and not much later than 320o B.c. Prof. Sir Flinders Petrie thinks it began 146o years earlier (see CHRONOLOGY), but he stands alone in this belief, as also does Dr. Borchardt in his un usual date (about 4000 B.c.). A recent writer, Dr. Scharff, would bring the date down to about 300o B.c. And it must be admitted that his arguments are good, and that at any rate it is more prob able that the date of the First Dynasty is later than 3400 B.C. than earlier (see CHRONOLOGY). The most generally accepted date is c. 320o B.C. (Meyer). We may guess that S.D. 5o may represent anything round about 4000 B.C. Now copper is first found at S.D. 38, and a fine copper dagger from Nagada dates between S.D. 55 and 6o. The Egyptians therefore ceased to be purely neolithic probably well before 4000 B.C. More we cannot say.

The Chalcolithic Age.

It must not be supposed that with the introduction of metal, stone weapons and tools suddenly went out of use. During the whole of the chalcolithic age, from the middle of the pre-dynastic period to the time of the 13th Dynasty, roughly two thousand years, stone was used for commoner pur poses, side by side with copper; butcher's knives, for instance, were still made of flint under the 12th Dynasty, and arrow-heads of flint were naturally still used, since it was senseless to waste metal on a weapon that could not be retrieved.

The introduction of metal meant

a rapid advance in civilization, and by the end of the pre-dynastic period Egypt had developed from a land inhabited by barbarian tribes into a civilized nation with a complicated polity and a culture to which art and even luxury were not unknown. The brain of the nation developed with great speed, and we find that long before the beginning of the Dynasty an astronomical calendar had appeared and must have been first used (see CALENDAR) in 4241-4238 B.C., unless with Scharff we suppose that it was first invented a Sothic period later, about 2781-2778 B.C., and in the reign of Zoser of the 3rd Dy nasty, whose date he brings down so late as this (see CHRO NOLOGY). There is no doubt that the impulse to this development, and probably the introduction of metal itself, was due to influences from Syria, and it is probable that already in the middle of the pre-dynastic period the infiltraticn of non-Nilotic broad-headed foreigners from the North had begun which ended in the domi nation of the nation by a royal and aristocratic tribe of Asiatics of much higher cranial capacity than the indigenes, who gradually mingled with the Nilotic natives and founded the historical civili zation of Egypt. Both elements (and also a third, the Libyan from the West, akin to the Nilote) made their contribution to the common culture ; to the indigenous Nilotes belong probably the more distinctly Nilotic and African characteristics, the ani mal gods for instance, and their representation on what have in correctly been called "totem-poles" and perches (we find similar insignia borne in the boats painted on the prehistoric pottery), and the earlier method of burial; to the northern invaders the gods in human form (we find the two elements side by side later when a human-headed god has his animal incarnation beside him), especially the god Osiris who certainly came with more highly developed agriculture from Syria (he was primarily a corn-god, and only connected with the dead by identification with the old indigenous deity of the necropoles [see CHRONOLOGY] ) and the political institutions of the kingdom ; while the Libyans contrib uted peculiar elements of their own. By the time of the foundation of the kingdom the fusion of the two chief races had progressed far, and it was probably to a royal house of the invading stock long settled in Upper Egypt that the conquest of the North was due which laid the foundation of the united kingdom of the North and South which persisted in spite of periodical fallings apart, until the end (see History).In all probability the coming of the northerners modified the language (which seems to be a mixture of "Semitic" and Nilotic elements) and they probably introduced a primitive picture writing of their own (equally the original of the Sumerian script from which in Mesopotamia cuneiform developed), which started the development of the Egyptian hieroglyphic system. This also certainly included a large Nilotic element derived from the natives.