The Revolutionary Period

THE REVOLUTIONARY PERIOD, 1789-1832 Under the seeming immobility of the Georgian era potent forces were working for change. By 1789 the Industrial Revolu tion (q.v.) was beginning to drive weavers and spinsters from the cottage to the factory, and to deplete the eastern and southern districts in favour of the north and west where water-power and coal were abundant. The new townships, dependent on nature's forces and man's inventions, cared little for tradition and began to chafe at control by a parliament representing imperfectly even the old agricultural England. The ever growing commercial class also became politically clamant. Above all, there now came from France a clarion call for freedom and equality which awakened echoes even in the semi-somnolent England of George III. Yet the French and English movements for reform, though alike aiming at the freedom of man from outworn laws, were destined to clash, with results infinitely disastrous. To outline the chief causes and consequences of this collision is here the guiding pur pose.

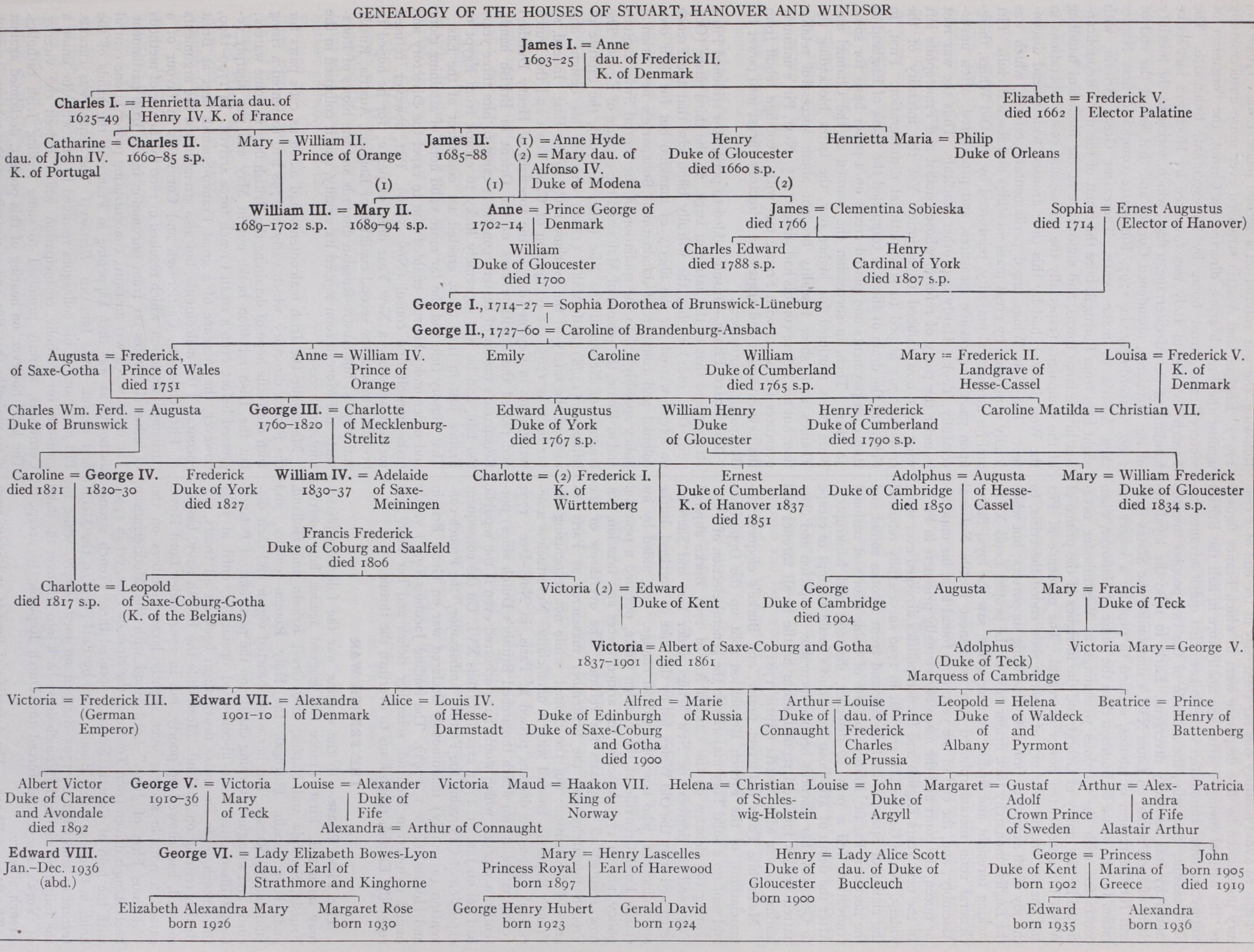

First, to avoid hostility was far from easy at the end of a cen tury punctuated by five desperate wars in which France figured as "the natural enemy." After she finally tore in half the British empire, national animosities were so keen that quick advance im plied assault. Secondly, the attitude of the two peoples towards monarchy was curiously divergent. Early in 1789 the loyal ac claim of the French, on Louis XVI.'s summoning the States Gen eral for the reform of abuses, seemed to promise a longer du ration for the house of Bourbon than the house of Hanover, when contrasted with the factious wranglings at Westminster occa sioned by the lunacy of George and the intrigues of the prince of Wales for unrestricted power as regent. The prudence of Pitt and the opportune recovery of George soon ended the crisis, to the joy of all except the prince and his Whig supporters; but while the English monarchy took firmer hold of the people, Louis XVI., lacking foresight and finding no sure guide, saw the loyal States General soon metamorphosed into an almost hostile National Assembly; and, the end of the year 1789 found him, his unpopu lar queen, the court and the assembly virtually prisoners in Paris. In the next years English and French politics diverged ever more widely. While George III. and Pitt in 1790 successfully rebutted the claims of Spain to exclude England from Nootka sound and the northern Pacific, France, in spite of noble efforts at national renovation, fell a prey to disorder, discredit and bankruptcy. After the death of Mirabeau and Louis's futile attempt to escape to Germany, her discords became incurable. Suspicion and class hatred bred a fanatical republicanism hostile to all thrones and leading to war with Austria (April, 1792).

Meanwhile Fox's indiscreet praise, and Burke's eloquent de nunciations, of the French Revolution split up the Opposition and sent up a solid Tory majority in the general election of 179o. During the debates on the Canada Act of 1791 Burke abjured Fox; and by degrees the New Whigs under Fox and Sheridan separated from the Old Whigs, led by the duke of Portland, Burke and Windham, who now opposed all change. Pitt, aided by his cousin Lord Grenville at the Foreign Office, pursued a peaceful policy, and in 1792 lessened the armed forces and taxation, but now scouted all proposals for reform. The overthrow of the French monarchy and the September massacres at Paris in creased the tension; but the cabinet, while not recognizing the French Republic, treated with it unofficially. Nevertheless a se ries of aggressive decrees passed at Paris, in Nov.–Dec., 1792 (culminating in two which threatened Britain's Dutch allies) por tended a rupture, which would have occurred even if the republic had not on Jan. 21, 1793, executed Louis XVI. On the consequent expulsion of Chauvelin, the French "ambassador," the French con vention (assembly) unanimously declared war on Great Britain and Holland (Feb. I, 1793). The leading Jacobins (q.v.) vainly hoped to overrun Holland, seize her riches and her fleet, and rouse the English republicans to overturn the throne.