in Gases Conduction of

CONDUCTION OF, IN GASES A gas such as air when it is under normal conditions conducts electricity to a small but only to a very small extent, however small the electric force acting on the gas may be. The electrical conductivity of gases not exposed to special conditions is so small that it was only definitely established in the early years of the loth century, although it had engaged the attention of physicists for more than a hundred years. It had been known for a long time that a body charged with electricity slowly lost its charge even when insulated with the greatest care, and though long ago some physicists believed that part of the leak of electricity took place through the air, the general view seems to have been that it was due to almost unavoidable defects in the insulation or to dust in the air, which after striking the charged body was repelled from it and went off with some of the charge. C. A. Coulomb, who made some very careful experiments which were published in 1785 (Mem. de l'Acad. des Sciences, 1785, p. 612), came to the conclusion that after allowing for the leakage along the threads which supported the charged body there was a balance over, which he attributed to leakage through the air. His view was that when the molecules of air come into contact with a charged body some of the electricity goes on to the mole cules, which are then repelled from the body carrying their charge with them. We shall see later that this explanation is not tenable. C. Matteucci (Ann. claim. phys., 185o, 28, p. 39o) in 185o also came to the conclusion that the electricity from a charged body passes through the air ; he was the first to prove that the rate at which electricity escapes is less when the pressure of the gas is low than when it is high. He found that the rate was the same whether the charged body was surrounded by air, carbonic acid or hydrogen. Subsequent investigations have shown that the rate in hydrogen is in general much less than in air. Thus in 1872 E. G. Warburg (Pogg. Ann,, 1872, P. found that the leak through hydrogen was only about one-half of that through air : he confirmed Matteucci's observations on the effect of pressure on the rate of leak, and also found that it was the same whether the gas was dry or damp. He was inclined to attribute the leak to dust in the air, a view which was strengthened by an experiment of J. W. Hittorf's (Wied. Ann., 7, p. 595), in which a small carefully insulated electroscope, placed in a small vessel filled with carefully filtered gas, retained its charge for several days ; we know now that this was due to the smallness of the vessel and not to the absence of dust, as it has been proved that the rate of leak in small vessels is less than in large ones.

Great light was thrown on this subject by some experiments on the rates of leak from charged bodies in closed vessels made almost simultaneously by H. Geitel (Plays. Zeit., 1900, 2, p. I16) and C. T. R. Wilson (Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc., 1900, I I, p. 32). These observers established that (I) the rate of escape of electricity in a closed vessel is much smaller than in the open, and the larger the vessel the greater is the rate of leak; and (2) the rate of leak does not increase in proportion to the differences of potential between the charged body and the walls of the vessel: the rate soon reaches a limit beyond which it does not increase, however much the potential difference may be increased, provided, of course, that this is not great enough to cause sparks to pass from the charged body. On the assumption that the maximum leak is proportional to the volume, Wilson's experiments, which were made in vessels less than 1 litre in volume, showed that in dust-free air at atmospheric pressure the maximum quantity of electricity which can escape in one second from a charged body in a closed volume of V cubic centimetres is about electrostatic units.

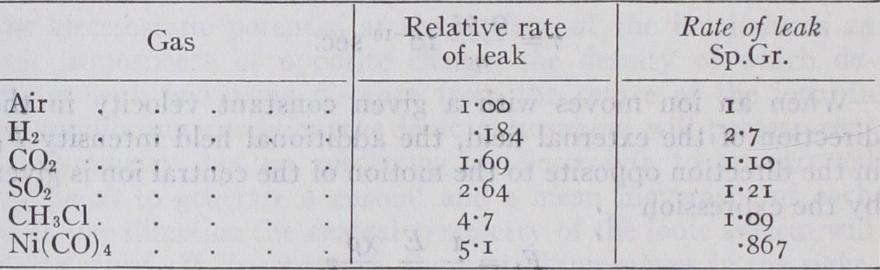

E. Rutherford and S. T. Allan (Phys. Zeit., 1902, 3, p. 225), working in Montreal, obtained results in close agreement with this. Working between pressures of from 43 to 743 millimetres of mercury, Wilson showed that the maximum rate of leak is very approximately proportional to the pressure ; it is thus exceedingly small when the pressure is low-a result illustrated in a striking way by an experiment of Sir W. Crookes (Proc. Roy. Soc., 1879, 28, p. 347) in which a pair of gold leaves retained an electric charge for several months in a very high vacuum. Subsequent experiments have shown that it is only in very small vessels that the rate of leak is proportional to the volume and to the pressure; in large vessels the rate of leak per unit volume is considerably smaller than in small ones. In small vessels the maximum rate of leak in different gases, is, with the exception of hydrogen, approximately proportional to the density of the gas. Wilson's results on this point are shown in the following table (Proc. Roy. Soc., 190I, 6o, p. The rate of leak of electricity through gas contained in a closed vessel depends to some extent on the material of which the walls of the vessel are made ; thus it is greater, other circumstances being the same, when the vessel is made of lead than when it is made of aluminium. It also varies, as Campbell and Wood (Phil. Mag. [6], 13, p. 265) have shown, with the time of the day, having a well-marked minimum at about 3 o'clock in the morning : it also varies from month to month. Rutherford (Phys. Rev., 1903, 16, p. 183), Cooke (Phil. Meg., 1903 [6], 6, p. 403) and M'Clennan and Burton (Phys, Rev., 1903, 16, p. 184) have shown that the leak in a closed vessel can be reduced by about 3o% by surrounding the vessel with sheets of thick lead, but that the reduction is not increased beyond this amount, however thick the lead sheets may be. This result indicates that part of the leak is due to a very penetrating kind of radiation, which can get through the thin walls of the vessel but is stopped by the thick lead. A large part of the leak we are describing is due to the presence of radioactive substances such as radium and thorium in the earth's crust and in the walls of the vessel, and to the gaseous radioactive emanations which diffuse from them into the atmosphere. This explains the very interesting effect dis covered by J. Elster and H. Geitel (Phys. Zeit., 1901, 2, p. 56o), that the rate of leak in caves and cellars when the air is stagnant and only renewed slowly is much greater than in the open air.

In some cases the difference is very marked; thus they found that in the cave called the Baumannshohle in the Harz mountains the electricity escaped at seven times the rate it did in the air outside. In caves and cellars the radioactive emanations from the walls can accumulate and are not blown away as in the open air.

The conductivity of normal air arises from several causes; part of it may be due to the presence of radioactive substances in the walls of the vessel in which the gas is contained, or to a little radio active emanation in the gas itself. The conductivity is so small that a mere trace of radioactive substances or of radioactive properties in ordinary matter would be sufficient to account for it. The metal of the containing vessel has certainly a consider able effect on the conductivity of the gas inside; this may, how ever, be due not to an intrinsic radiation of the metal but to a radiation excited by the passage through the metal of a very penetrating radiation for the existence of which there is strong evidence. That the intrinsic radioactivity of the metal and gas cannot be the sole cause of the conductivity is shown by experi ments like that made by M'Clennan (Phil. Mag., v. 24, p. 520, 1912), who measured the conductivity in a hermetically sealed vessel in Canada, England and Scotland and on board a steam ship in the Atlantic ; he found that the conductivity was much the same at the different land stations, and could be represented by the production of about 9 ions per c.c. of the gas per sec., but that the conductivity over the sea was considerably less, and was equivalent to only 6 ions per c.c. per sec. This indicates that some of the conductivity of the gas is due to radiation coming from the land, and that this radiation is cut off by the ocean. This is confirmed by the fact discovered by M'Clennan and McCallum (Phil. Mag., vi. 22, p. 629, 1911), Wulf (Phys. *Tech. xi. p. 811) and Bergwitz (Hahlibakonschrift, Brunswick, 1910) that at the top of high towers the conductivity is less than on the ground; this is what we should expect since the radiation is ab sorbed by the atmosphere. Observations on the conductivity of the air in vessels taken up in balloons by Gockel (Phys. Zeit., x. p. 1909; xii. P. 595, 191 I), Hess (Phys. Zeit., xii. p. 998, 191 1 ), and especially by Kolhorster (Plays. Zeit., xiv. pp. 1066, 1913, Deutsch. Phys. Gesell. V erh., xvi. 14, P. 719, 1914) have brought to light the very interesting fact that the diminution in the conductivity with height ceases when the height exceeds some two kilometres and at greater altitudes is succeeded by an increase in conductivity with altitude.

Kolhorster found that at the height of nine kilometres the con ductivity in a sealed vessel was some ten times that at the surface of the earth. These variations of the conductivity with the height are what would occur if the conductivity were produced by radia tions of two different types (I) a radiation coming from the ground and (2) another coming from the sky. The effects due to (I) would diminish as the height increased while that due to (2) would increase. Estimates of the amount of conductivity due to (2) at the surface of the earth have been made by various observ ers, and it would seem that it may be represented by the produc tion of about 1•5 ions per c.c. per sec. ; as the conductivity at sea level generally requires the production of from 10-20 ions per c.c. per sec. ; much the greater part of the conductivity at the earth's surface must be due to radiation of type 1. Millikan and Bowen give the following results for the conductivity due to radiation of type 2 at different altitudes, the numbers being the number of ions produced per c.c. per sec.: 1.4 at sea-level, 2.6 at 1,600 metres, 4.8 at 1,600 metres, 5.9 at 4,30o metres. Kolhorster (Berlin, Berichte, 1923, p. 366) by making observations at the surface, and in caverns of glaciers on the Jungfrau, measured the absorption of these rays by ice, and found an absorption coefficient of about 2.5 per metre; this is much smaller than that of the y radiation from any known radioactive substance. He found a diurnal variation in the amount of the radiation and suggested that it might be connected with the Milky Way.

Many observations on this radiation have been made by Mil likan and his collaborators (Nature, Jan. 7, 1928), who have meas ured the conductivity in vessels submerged at different depths in two mountain lakes on Mount Whitney. Lake Muir, at an altitude of 11,80o ft., and Arrowhead lake at an altitude of 5,100. These lakes are fed by melted snow so that the water is not likely to contain radioactive matter. It appears from these measurements that the radiation is by no means homogeneous, as the absorption coefficient was greater at the surface of the lake than at the greatest depth at which observations were taken. No trace of the diurnal effect observed by Kolhorster was detected. It was found, too, from observations made in the southern hemisphere on the Andes in Bolivia, that both the character and the amount of the radiation was much the same in the two hemispheres, indicating that the radiation comes pretty uniformly from all parts of the heavens. Applying an expression due to Compton for the connection between the absorption and wave-length it was found that the wave length of the most penetrating radiation was .00038 A; the quantum of energy corresponding to this wave-length is about 32 million volts. This is much greater than the energy associated with any known y radiation. Many suggestions have been made as to its origin. Jeans and Eddington have suggested that it arises from the coalescence of an electron with a positive particle and the conversion of their energy and mass into those of radiation; this would give a radiation more penetrating than that found though it might be degraded by passing through matter. C. T. R. Wilson has suggested the possibility of the radiation being excited by electrons which have acquired energy amounting to millions of volts under the action of something analogous to thunderstorms. This is in accordance with the laws which govern the passage of electrons through gases but Millikan finds no dif ference in the amount of radiation in regions where thunderstorms are frequent and in those where they are rare. We do not know enough at present about these rays to decide either as to their nature or the place of their origin ; it is evident, however, that they raise questions of the greatest interest and importance.

The electrical conductivity of gases in the normal state is, as we have seen, exceedingly small, so small that the investigation of its properties is a matter of considerable difficulty; there are, how ever, many ways by which the electrical conductivity of a gas can be increased so greatly that the investigation becomes compara tively easy. Gases drawn from the neighbourhood of flames, elec tric arcs and sparks, or glowing pieces of metal or carbon are con ductors, as are also gases through which Rontgen or cathode rays or rays of positive electricity are passing; the rays from the radio active metals, radium, thorium, polonium and actinium, produce the same effect, as does also ultra-violet light of exceedingly short wave-length. The gas, after being made a conductor of electricity by any of these means, is found to possess certain properties; thus it retains its conductivity for some little time after the agent which made it a conductor has ceased to act; the conductivity, however, diminishes very rapidly and finally gets too small to be appreciable.

This and several other properties of conducting gas may readily be proved by the aid of the apparatus represented in fig. 1. V is a testing vessel in which an electroscope is placed. Two tubes A and C are fitted into the vessel, A being connected with a water pump, while the f end of C is in the region where the gas is exposed to the agent, which makes it a conductor of electricity.

Let us suppose that the gas is made conducting by Rontgen rays produced by a vacuum tube which is placed in a box, covered except for a window at B with lead so as to protect the electro scope from the direct action of the rays. If a slow current of air is drawn by the water pump through the testing vessel, the charge on the electroscope will gradually leak away. The leak, however, ceases when the current of air is stopped. This result shows that the gas retains its conductivity during the time taken by it to pass from one end to the other of the tube C.

The gas loses its conductivity when filtered through a plug of glass-wool, or when it is made to bubble through water. This can readily be proved by inserting in the tube C a plug of glass wool or a water trap; then if by working the pump a little harder the same current of air is produced as before, it will be found that the electroscope will now retain its charge, showing that the conductivity can, as it were, be filtered out of the gas. • The con ductivity can also be removed from the gas by making the gas traverse a strong electric field. We can show this by replacing the tube C by a metal tube with an insulated wire passing down the axis of the tube. If there is no potential difference between the wire and the tube then the electroscope will leak when a current of air is drawn through the vessel, but the leak will stop if a con siderable difference of potential is maintained between the wire and the tube : this shows that a strong electric field removes the conductivity from the gas.

The fact that the conductivity of the gas is removed by filtering shows that it is due to something mixed with the gas which is removed from it by filtration, and since the conductivity is also removed by an electric field, the cause of the conductivity must be charged with electricity so as to be driven to the sides of the tube by the electric force. Since the gas as a whole is not electrified either positively or negatively, there must be both negative and positive charges in the gas, the amount of electricity of one sign being equal to that of the other. We are thus led to the conclusion that the conductivity of the gas is due to electrified particles being mixed up with the gas, some of these particles having charges of positive electricity, others of negative. These electrified particles are called ions, and the process by which the gas is made a con ductor is called the ionization of the gas. We shall show later that the charges and masses of the ions can be determined, and that the gaseous ions are not identical with those met with in the electrolysis of solutions.

One very characteristic property of conduction of electricity through a gas is the relation between the current through the gas and the electric force which gave rise to it. This relation is not in general that expressed by Ohm's law, which always, as far as our present knowledge extends, expresses the relation for conduction through metals and electrolytes. With gases, on the other hand, it is only when the current is very small that Ohm's law is true. If we represent graphically by means of a curve the relation be tween the current passing between two parallel metal plates separated by ionized gas and the difference of potential between the plates, the curve is of the character shown in fig. 2, when the ordinates rep resent the current and the abscissae the dif ference of potential between the plates.

We see that when the potential difference is very small, i.e., close to the origin, the curve is approximately straight, but that soon the current increases much less rapidly than the potential difference, and that a stage is reached when no appreciable increase of current is produced when the potential difference is increased ; when this stage is reached the current is constant, and this value of the current is called the "saturation" value. When the potential difference approaches the value at which sparks would pass through the gas, the current again increases with the potential difference; thus the curve repre senting the relation between the current and potential difference over very wide ranges of poten tial difference has the shape shown in fig. 3; curves of this kind have been obtained by von Schweidler (Wien. Ber., 1899, 108, p. 273), and J. E. S. Town send (Phil. Mag., 1901 [6], 1, p.

198). We shall discuss later the causes of the rise in the current with large potential differences, when we consider ionization by collision.

The general features of the earlier part of the curve are readily explained on the ionization hypothesis. On this view the Rontgen rays or other ionizing agent acting on the gas between the plates, produces positive and negative ions at a definite rate. Let us sup pose that q positive and q negative ions are by this means pro duced per second between the plates; these under the electric force will tend to move, the positive ones to the negative plate, the negative ones to the positive. Some of these ions will reach the plate, others before reaching the plate will get so near one of the opposite sign that the attraction between them will cause them to unite and form an electrically neutral system ; when they do this they end their existence as ions. The current between the plates is proportional to the number of ions which reach the plates per second. Now it is evident that we cannot go on taking more ions out of the gas than are produced; thus we cannot, when the current is steady, have more than q positive ions driven to the negative plate per second, and the same number of negative ions to the positive. If each of the positive ions carries a charge of e units of positive electricity, and if there is an equal and opposite charge on each negative ion, then the maximum amount of elec tricity which can be given to the plates per second is qe, and this is equal to the saturation current. Thus if we measure the satura tion current, we get a direct measure of the ionization, and this does not require us to know the value of any quantity except the constant charge on the ion. If we attempted to deduce the amount of ionization by measurements of the current before it was sat urated, we should require to know in addition the velocity with which the ions move under a given electric force, the time that elapses between the Iiberation of an ion and its combination with one of the opposite sign, and the potential difference between the plates. Thus if we wish to measure the amount of ionization in a gas we should be careful to see that the current is saturated.

The difference between conduction through gases and through metals is shown in a striking way when we use potential differences large enough to produce the saturation current. Suppose we have got a'potential difference between the plates more than sufficient to produce the saturation current, and let us increase the distance between the plates. If the gas were to act like a metallic con ductor this would diminish the current, because the greater length would involve a greater resistance in the circuit. In the case we are considering the separation of the plates will increase the current, because now there is a larger volume of gas exposed to the rays; there are therefore more ions produced, and as the saturation current is proportional to the number of ions the saturation current is increased. If the potential difference between the plates were much less than that required to saturate the current, then increasing the distance would diminish the current ; the gas for such potential differences obeys Ohm's law and the behaviour of the gaseous resistance is therefore similar to that of a metallic one.

In order to produce the saturation current the electric field must be strong enough to drive each ion to the electrode before it has time to enter into combination with one of the opposite sign. Thus when the plates in the preceding example are far apart, it will take a larger potential difference to produce this current than when the plates are close together. The potential difference required to saturate the current will increase as the square of the distance between the plates, for if the ions are to be delivered in a given time to the plates their speed must be pro portional to the distance between the plates. But the speed is proportional to the electric force acting on the ion; hence the electric force must be proportional to the distance between the plates, and as in a uniform field the potential difference is equal to the electric force multiplied by the distance between the plates, the potential difference will vary as the square of this distance.

The potential difference required to produce saturation will, other circumstances being the same, increase with the amount of ionization, for when the number of ions is large and they are crowded together, the time which will elapse before a positive one combines with a negative will be smaller than when the number of ions is small. The ions have therefore to be removed more quickly from the gas when the ionization is great than when it is small; thus they must move at a higher speed and must there fore be acted upon by a larger force.

When the ions are not removed from the gas, they will increase until the number of ions of one sign which combine with ions of the opposite sign in any time is equal to the number produced by the ionizing agent in that time. We can easily calculate the number of free ions at any time after the ionizing agent has com menced to act.

Coefficient of Recombination.-Let

q be the number of ions (positive or negative) produced in one cubic centimetre of the gas per second by the ionizing agent, the number of free positive and negative ions respectively per cubic centimetre of the gas. The number of collisions between positive and negative ions per second in one cubic centimetre of the gas is proportional to If a certain fraction of the collisions between the positive and negative ions result in the formation of an electrically neutral system, the number of ions which disappear per second in a cubic centimetre will be equal to where a is a quantity which is independent of n2; hence if t is the time since the ionizing agent was applied to the gas, we have = q - = q - and n2.Thus is constant, so if the gas is uncharged to begin with, will always equal Putting n we have if a. Now the number of ions when the gas has reached a steady state is got by putting t equal to infinity in the preceding equation, and is therefore given by the equation = k= Al(q/a) We see from equation (2) that the gas will not approximate to its steady state until 2kat is large, that is until t is large compared with i/2ka or with a). We may thus take a) as a measure of the time taken by the gas to reach a steady state when exposed to an ionizing agent ; as this time varies inversely as we see that when the ionization is feeble it may take a very considerable time for the gas to reach a steady state. Thus in the case of our atmosphere where the production of ions is only at the rate of about 3o per cubic centimetre per second, and where, as we shall see, a is about 0 it would take some minutes for the ionization in the air to get into a steady state if the ionizing agent were suddenly applied.

We may use equation (I) to determine the rate at which the ions disappear when the ionizing agent is removed. Putting q = o in that equation we get dn/ at= ant.

Hence n = (3), where is the number of ions when t =o. Thus the number of ions falls to one-half its initial value in the time 1/m a. The quantity a is called the coefficient of recombination, and its value for different gases has been determined by Rutherford (Phil. Mag. 1897 [5], 44, P. 422), Townsend (Phil. Trans., 19oo, 193, P. 129), McClung (Phil. Mag., 1902 [6], 3, p. 283), Langevin (Ann. chim. phys. [7], 28, p. 289), Retschinsky (Ann. d. Phys., 1905, 17, p. 518), Hendred (Phys. Rev. 1905, 21, p. 314), Rumelin (Phys. Zeits., ix. p. 657, 1908), Thirkill (Proc. Roy. Soc., 87, p. 477, 1913), Erikson (Phil. Mag., vi. 18 p. 328, 1909; P. 747, 1912). The values of a/e, a being the charge on an ion in electro static measure as determined by these observers for different gases, is given in the following table: The gases in these experiments were carefully dried and free from dust; the apparent value of a is much increased when dust or small drops of water are present in the gas, for then the ions get caught by the dust particles, the mass of a particle is so great compared with that of an ion that they are practically immovable under the action of the electric field, and so the ions clinging to them escape detection when electrical methods are used. Taking e as 4.77X 1 we see that a is about 1.6X i o so that the number of recombinations in unit time between n positive and n negative ions in unit volume is 1.6X The kinetic theory of gases shows that with 2n molecules of air per cubic centimetre the number of collisions per second is 4 X at a temperature of o° C. Thus we see that the number of recombinations between oppositely charged ions is enormously greater than the number of collisions between the same number of neutral molecules. We shall see that the difference in size between the ion and the mole cule is not nearly sufficient to account for the difference between the collisions in the two cases; the difference is due to the force between the oppositely charged ions, which drags ions into col lisions which but for this force would have missed each other.

Several methods have been used to measure a. In one method air, exposed to some ionizing agent at one end of a long tube, is slowly sucked through the tube and the saturation current meas ured at different points along the tube. These currents are pro portional to the values of is at the place of observation : if we know the distance of this place from the end of the tube when the gas was ionized and the velocity of the stream of gas, we can find t in equation (3), and knowing the value of n we can deduce the value of a from the equation where are the values of n at the times respectively. In this method the tubes ought to be so wide that the loss of ions by diffusion to the sides of the tube is negligible. This method does not involve the mobility of the ions, i.e., the speed they acquire under electric forces. Another method which has the same advantage is due to Rumelin. In this the gas is exposed con tinuously to the ionizing agent, while the electric field is applied to the gas by means of a rotating sector and is adjusted so as to be zero during one part of the revolution of the sector and great enough to produce saturation during the remainder. The current sent through the gas by this field is measured and from it the value of a can be calculated. There are other methods which involve the knowledge of the mobility of the ions ; we shall defer the consideration of these methods until we have discussed this question.

In measuring the value of a it should be remembered that the theory of the methods supposes that the ionization is uniform throughout the gas. If the total ionization throughout a gas re mains constant, but instead of being uniformly distributed is con centrated in patches, it is evident that the ions will recombine more quickly in the second case than in the first, and that the value of a will be different in the two cases. This probably ex plains the large values of a obtained by Retschinsky, who ionized the gas by the a rays from radium, a method which produces very patchy ionization.

Variation of a with the Pressure of the Gas.-This question was first investigated by Langevin (Ann. Chem. Phys., 1903, 28, p. 287) who found that at low pressures a was less than at high, thus at the pressure of one-fifth of an atmosphere the value of a for air was about one-fifth of that at atmospheric pressure. He showed, too, that the value of a reached a maximum at a certain pressure-for air about two atmospheres- and fell away fairly rapidly with any further increase in pressure. A very valuable investigation of the effect of pressure on the value of a was made by Thirkill (Proc. Roy. Soc., 88, p. 477, 1913), who showed that for pressures not exceeding one atmosphere a is very approximately a linear function of the pressure, the gases he investigated were air, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, sul phur dioxide and nitrous oxide.

Variation of a with Temperature.-The

variation of a with temperature has been investigated for air, carbonic acid and hydrogen at constant density when ionized by a rays by Erik son (Phil. Meg., vi. 18, p. 328, 1909; 23, P. 747, 1912) and for air at constant pressure ionized by X-rays by Phillips (Proc. Roy. Soc. A. 83, p. 246, 191o) . It was found that over a very wide range of temperature a for hydrogen can be repre sented by a formula of the type a= when 0 is the abso lute temperature and C a constant, and though such a formula does not hold for air and carbonic acid at temperatures much below o° C, it represents the value of a with fair accuracy at higher temperatures. Erikson's experiments give n= 2.42, 2.3o, for air, carbonic acid and hydrogen respectively, while Phillips (at constant pressure) finds n= 2.

Diffusion of the Ions.-The

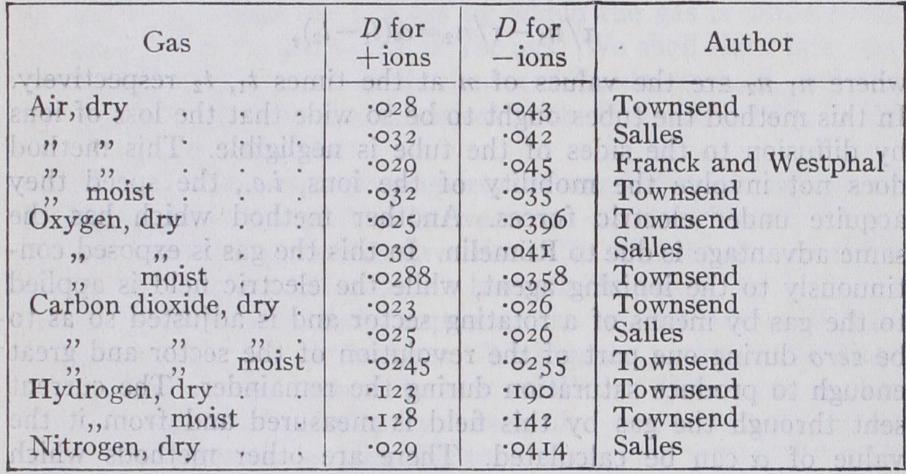

ionized gas acts like a mixture of gases, the ions corresponding to two different gases, the non ionized gas to a third. If the concentration of the ions is not uniform, they will diffuse through the non-ionized gas in such a way as to produce a more uniform distribution. A very valuable series of determinations of the coefficient of diffusion of ions through various gases has been made by Townsend (Phil. Trans., 1900, A, 193, p. 129) . The method used was to suck the ionized gas through narrow tubes; by measuring the loss of both the positive and negative ions after the gases had passed through a known length of tube, and allowing for the loss by recombina tion, the loss by diffusion and hence the coefficient of diffusion could be determined. Salles, Franck and Westphal have used similar methods. Salles found that the material of which the tubes are made has no influence on the diffusion. The following tables give the values of the coefficients of diffusion D on the C.G.S. system of units.

It is interesting to compare with these coefficients the values of D when various gases diffuse through each other. D for hydro gen through air is .634, for oxygen through air .177, for the vapour of isobutyl amide through air -042. We thus see that the velocity of diffusion of ions through air is much less than that of the simple gas, but that it is quite comparable with that of the vapours of some complex organic compounds.

The preceding tables show that the negative ions diffuse more rapidly than the positive, especially in dry gases. The superior mobility of the negative ions was observed first by Zeleny (Phil. Mag., 1898 [5], 46, p. 120), who showed that the velocity of the negative ions under an electric force is greater than that of the positive. It will be noticed that the difference between the mo bility of the negative and the positive ions is much more pro nounced in dry gases than in moist. The difference in the rates of diffusion of the positive and negative ions is the reason why ionized gas, in which, to begin with, the positive and negative charges were of equal amounts, sometimes becomes electrified even although the gas is not acted upon by electric forces. Thus, for example, if such gas be blown through narrow tubes, it will be positively electrified when it comes out, for since the negative ions diffuse more rapidly than the positive, the gas in its passage through the tubes will lose by diffusion more negative than posi tive ions and hence will emerge positively electrified. Zeleny showed that this effect does not occur when, as in carbonic acid gas, the positive and negative ions diffuse at the same rates. Townsend (loc. cit.) showed that the coefficient of diffusion of the ions is the same whether the ionization is produced by Röntgen rays, radioactive substances, ultra-violet light, or elec tric sparks. The ions produced by chemical reactions and in flames are much less mobile ; thus, for example, Bloch (Ann. chim. phys., [8], 4, p. 25) found that for the ions produced by drawing air over phosphorus the value of a/e was between I and 6 instead of over 3,000, the value when the air was ionized by Röntgen rays.

Velocity of Ions in an Electric Field.-The

velocity of ions in an electric field, which is of fundamental importance in conduction, is very closely related to the coefficient of diffusion. Measurements of this velocity for ions produced by Rontgen rays have been made by Rutherford (Phil. Mag. [5], 44, p. 422), Zeleny (Phil. Mag. [5], 46, p. 12o), Langevin (Ann. Chim. Phys., 1903, 28, p. 289), Phillips (Proc. Roy. Soc. 78, A, p. 167), and Wellisch (Phil. Trans., 1909, p. . The ions pro duced by radioactive substance have been investigated by Ruther ford (Phil. Mag. [5], 47, p. 109) and by Franck and Pohl (Verh. deutsch. phys. Gesell., 1907, 9 p. 69), Tyndall and Grindley (Proc. Roy. Soc., A, no, p. 341; Laporte, C.R. 172, p. 1028, 1921 ; 182, pp. 62o-781, 1926; 183, pp. 119-287), and the negative ions produced when ultra-violet light falls on a metal plate by Ruther ford (Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 9, P. 401), Townsend and Tizard (Proc. Roy. Soc., A, p. H. A. Wilson (Phil. Trans. 192, p. 409), Marx (Ann. de Phys. I p. 765) ; Moreau (Journ. de Phys. 4, II, p. 558; Ann. Chim. Phys. 7, 30, p. 5) and Gold (Proc. Roy. Soc. 79, P. 43) have investigated the velocities of ions produced by putting various salts into flames; McClelland (Phil. Mag. 46, p. 29) the velocity of the ions in gases sucked from the neighbourhood of flames and arcs; Townsend (Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 9, P. 345) and Bloch (loc. cit.) the velocity of ions produced by chemical reaction; and Chattock (Phil. Mag. [5] , p. 401) and Franck (Ann. der. Phys., 21, p. 972, 1908), the velocity of the ions produced when electricity escapes from a sharp needle point into a gas. Though so much work has been done on the mobility of the ions there are many points which are still unsettled. The experiments of the earlier observers were more discordant than could be accounted for by errors of observation; in some cases, indeed, they were contradictory. We know now that the mobility of the ions is profoundly affected by causes which at first sight appear trivial and may well have escaped specification in the earlier experiments. One of these causes is the age of the ions, the mobility of a freshly formed ion is often greater than that of an older one, a fact brought out clearly by Erikson's experiments; thus since the age of the ion influences its mobility, observers would obtain different results unless by chance it happened that the time which elapsed between the formation of the ion and the time that it came under observa tion was the same in the two cases. Another reason for the want of agreement is that, as we shall see, minute traces of an impurity in the gas may produce very large effects on the mobility.Several methods have been employed to determine these veloci ties. The one most frequently employed is to find the electro motive intensity required to force an ion against the stream of gas moving with a known velocity parallel to the lines of electric force. Thus, of two perforated plane electrodes vertically over each other, suppose the lower to be positively, the upper negatively electrified, and suppose that the gas is streaming vertically down wards with the velocity V; then unless the upward velocity of the positive ion is greater than V, no positive electricity will reach the upper plate. If we increase the strength of the field between the plates, and hence the upward velocity of the positive ion, until the positive ions just begin to reach the upper plate, we know that with this strength of field the ve locity of the positive ion is equal to V. By this method, which has been used by Rutherford, Zeleny, H. A. Wilson and Erikson the ve locity of ions in fields of various strengths has been determined.

The arrangement used by Ze leny is represented in fig. 4. P and Q are square brass plates. They are bored through their centres, and to the openings the tubes R and S are attached, the space between the plates being covered in so as to form a closed box. K is a piece of wire gauze completely covering the opening in Q; T is an insulated piece of wire gauze nearly but not quite filling the opening in the plate P, and connected with one pair of quadrants of an electrometer E. A plug of glass wool G filters out the dust from a stream of gas which enters the vessel by the tube D and leaves it by F ; this plug also makes the velocity of the flow of the gas uniform across the section of the tube. The Rontgen rays to ionize the gas were produced by a bulb at 0, the bulb and coil being in a lead-covered box, with an aluminium window through which the rays passed. Q is connected with one pole of a battery of cells, P and the other pole of the battery are put to earth. The changes in the potential of T are due to ions giving up their charges to it. With a given velocity of air-blast the potential of T was found not to change unless the difference of potential between P and Q exceeded a critical value. The field corresponding to this critical value thus made the ions move with the known velocity of the blast.

Another method which has been employed by Rutherford and McClelland is based on the action of an electric field in destroy ing the conductivity of gas streaming through it. Suppose that BAB, DCD (fig.

5) are a system of parallel plates boxed so that a stream of gas, after flowing between BB, passes between DD without loss of gas in the interval. Suppose the plates DD are insulated, and connected with one pair of quadrants of an elec trometer, by charging up C to a sufficiently high potential we can drive all the positive ions which enter the system DCD against the plates D ; this will cause a deflexion of the electrometer, which in one second will be proportional to the number of posi tive ions which have entered the system in that time. If we charge A up to a high potential, B being put to earth, we shall find that the deflexion of the electrometer connected with DD is less than it was when A and B were at the same potential, because some of the positive ions in their passage through BAB are driven against the plates B. If a is the velocity along the lines of force in the uniform electric field between A and B, and t the time it takes for the gas to pass through BAB, then all the posi tive ions within a distance ut of the plates B will be driven up against these plates, and thus, if the positive ions are equally dis tributed through the gas, the number of positive ions which emerge from the system when the electric field is on will bear to the number which emerge when the field is off the ratio of I — ut/l to unity, where l is the distance between A and B. This ratio is equal to the ratio of the deflexions in one second of the electrometer attached to D, hence the observations of this instru ment give I —ut/l. If we know the velocity of the gas and the length of the plates A and B, we can determine t, and since l can be easily measured, we can find u, the velocity of the positive ion in a field of given strength. By charging A and C negatively instead of positively we can arrive at the velocity of the negative ion. In practice it is more convenient to use cylindrical tubes with coaxial wires instead of the systems of parallel plates, though in this case the calculation of the velocity of the ions from the observations is a little more complicated, inasmuch as the electric field is not uniform between the tubes.

A method which gives very accurate re sults, though it is only applicable in certain cases, is the one used by Rutherford to measure the velocity of the negative ions produced close to a metal plate by the in cidence on the plate of ultra-violet light.

The principle of the method is as follows:—AB (fig. 6) is an insulated horizontal plate of well-polished zinc, which can be moved vertically up and down by means of a screw; it is con nected with one pair of quadrants of an electrometer, the other pair of quadrants being put to earth. CD is a base-plate with a hole EF in it; this hole is covered with fine wire gauze, through which ultraviolet light passes and falls on the plate AB. The plate CD is connected with an alternating current dynamo, which produces a simply-periodic potential difference between AB and CD, the other pole being put to earth. Suppose that at any instant the plate CD is at a higher potential than AB, then the negative ions from AB will move towards CD, and will con tinue to do so as long as the potential of CD is higher than that of AB. If, however, the potential difference changes sign before the negative ions reach CD, these ions will go back to AB. Thus AB will not lose any negative charge unless the distance between the plates AB and CD is less than the distance traversed by the negative ion during the time the potential of CD is higher than that of AB. By altering the distance between the plates until CD just begins to lose a negative charge, we find the velocity of the negative ion under unit electromotive intensity. Suppose the difference of potential between AB and CD is equal to a sin pt, then if d is the distance between the plates the electric intensity is equal to a sin pt/d; if we suppose the velocity of the ion is proportional to the electric intensity; and if u is the velocity for unit electric intensity, the velocity of the negative ion will be ua sin pt/d. Hence if x represent the distance of the ion from AB dx ua = x = ua (I — cospt), if x = o when t = o.

p Thus the greatest distance the ion can get from the plate is equal to 2au/pd, and, if the distance between the plates is gradu ally reduced to this value, the plate AB will begin to lose a nega tive charge ; hence when this happens d = 2au/pd, or u = an equation by means of which we can find u.

Instead of using a harmonically varying field we may by a ro tating commutator apply a constant force for a certain time and then reverse the force taking care that the time it is applied after reversal is longer than the other time. Unless the ion can travel across the distance between the plates before the field is reversed the electrometer will not receive a charge; this gives the means of finding the mobility of the ions.

In this form the method is not applicable when ions of both signs are present. Franck and Pohl (Verb. deutsch. physik. Gesell. 1907, 9 p. 69) have by a slight modification removed this re striction. The modification consists in confining the ionization to a layer of gas below the gauze EF. If the velocity of the positive ions' is to be determined, these ions are forced through the gauze by applying to the ionized gas a small constant electric force acting upwards; if negative ions are required, the constant force is reversed. After passing through the gauze the ions are acted upon by alternating forces as in Rutherford's method. Loeb (Phys. Review, XXI., p. 72o, 1923) has shown that the disturbance of the electric field due to spreading of the lines of force due to the subsidiary field through the gauze may involve serious corrections to the simple theory.

Langevin

(Ann. chirn..phys., 1903, 28, p. 289) devised a method of measuring the velocity of the ions which has been extensively used ; it has the advantage of not requiring the rate of ionization to remain uniform. The general idea is as follows. Suppose that we expose the gas between two parallel plates A, B, to Röntgen rays or some other ionizing agent, then stop the rays and apply a uniform electric field to the region between the plates. If the force on the positive ion is from A to B, the plate B will receive a positive charge of electricity. After the electric force has acted for a time T reverse it. B will now begin to receive negative elec tricity and will go on doing so until the supply of negative ions is exhausted. Let us consider how the quantity of positive electricity received by B will vary with T. To fix our ideas, suppose the positive ions move more slowly than the negative; let and be respectively the times taken by the positive and negative ions to move under the electric field through a distance equal to AB, the distance between the planes. Then if T is greater than T2 all the ions will have been driven from between the plates before the field is reversed, and therefore the positive charge received by B will not depend upon T. Next let T be less than T2 but greater than then at the time when the field is reversed all the negative ions will have been driven from between the plates, so that the positive charge received by B will not be neu tralized by the arrival of fresh ions coming to it after the reversal of the field. The number of positive ions driven against the plate B will be proportional to T. Thus if we measure the value of the positive charge on B for a series of values of T, each value being less than the preceding, we shall find that until T reaches a certain value the charge remains constant, but as soon as we re duce the time below this value the charge diminishes. The value of T when the diminution in the field begins is T2, the time taken for a positive ion to cross from A to B under the electric field; thus from T2 we can calculate the velocity of the positive ion in this field. If we still further diminish T, we shall find that we reach a value when the diminution of the positive charge on B with the time suddenly becomes much more rapid; this change occurs when T falls below the time taken for the negative ions to go from one plate to the other, for now when the field is reversed there are still some negative ions left between the plates, and these will be driven against B and rob it of some of the positive charge it had acquired before the field was reversed. By observing the time when the increase in the rate of diminution of the positive charge with the time suddenly sets in we can determine and hence the velocity of the negative ions.The velocity of the ions produced by the discharge of elec tricity from a fine point was determined by Chattock by an entirely different method. In this case the electric field is so strong and the velocity of the ion so great that the preceding methods are not applicable. Suppose P represents a vertical needle discharging electricity into air, consider the force acting on the ions included between two horizontal planes A, B. If P is the density of the electrification, and Z the vertical com ponent of the electric intensity, F, the resultant force on the ions between A and B, is vertical and equal to Let us suppose that the velocity of the ion is proportional to the electric intensity, so that if w is the vertical velocity of the ions, which are supposed all to be of one sign, w = RZ.

Substituting this value of Z, the vertical force on the ions between A and B is equal to But ffwpdxdy = c, where c, is the current streaming from the point. This current, which can be easily measured by putting a galvanometer in series with the discharging point, is independent of z, the vertical distance of a plane between A and B below the charging point. Hence we have This force mu3t be counterbalanced by the difference of gaseous pressures over the planes A and B ; hence if PB and PA denote respectively the pressures over B and A, we have - PA = z.

Hence by the measurement of these pressures we can determine R, and hence the velocity with which an ion moves under a given electric intensity.

There are other methods of determining the velocities of the ions, but as these depend on the theory of the conduction of electricity through a gas containing charged ions, we shall con sider them in our discussion of that theory.

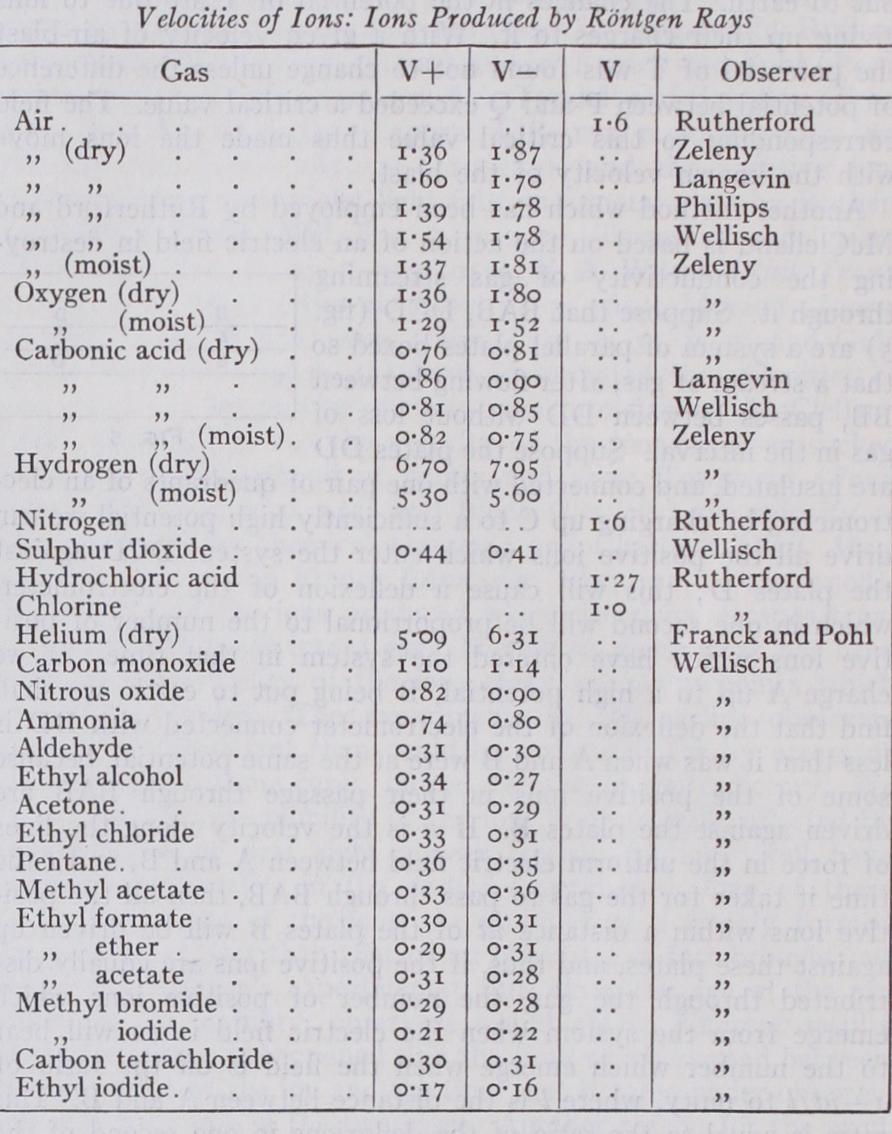

By the use of these methods it has been shown that the ve locities of the ions in a given gas are the same whether the ionization is produced by Röntgen rays, radioactive substances, ultra-violet light, or by the discharge of electricity from points. When the ionization is produced by chemical action the ions are very much less mobile, moving in the same electric field with a velocity less than one-thousandth part of the velocity of the first kind of ions. On the other hand, as we shall see later, the velocity of the negative ions in flames is enormously greater than that of even the first kind of ion under similar electric fields and at the same pressure. But when these negative ions get into the cold part of the flame, they move sluggishly with velocities of the order of those possessed by the second kind. The results of the various determinations of the velocities of the ions are given in the following table. The velocities are in centimetres per second under an electric force of one volt per centimetre, the pressure of the gas being i atmosphere. V+ denotes the velocity of the positive ion, V — that of the negative. V is the mean velocity of the positive and negative ions.

It will be seen from this table that the greater mobility of the negative ions is very much more marked in the case of the lighter and simpler gases than in that of the heavier and more complicated ones ; with the vapours of organic substances there seems but little difference between the mobilities of the positive and negative ions ; indeed in one or two cases the positive seem slightly but very slightly the more mobile of the two. In the case of the simple gases the difference is much greater when the gases are dry than when they are moist. It has been shown by direct experiment that the velocities are directly proportional to the electric force.

V rriation of Velocities with Pressure.

Until the pressure gets low the velocities of the ions, negative as well as positive, vary inversely as the pressure. Langevin (loc. cit.) was the first to show that at very low pressures the velocity of the negative ions increases more rapidly as the pressure is diminished than this law indicates. If the nature of the ion did not change with the pressure, the kinetic theory of gases indicates that the velocity would vary inversely as the pressure, so that Langevin's results indicate a change in the nature of the negative ion when the pressure is diminished below a certain value. Kovarik has determined the mobility of the negative ions in air and down to a pressure of i cm. and finds that at these low pressures the value of pV where p is the pressure and V the mobility increases rapidly as the pressure diminishes. The increase in the case of pV — indicates that the structure of the negative ion gets simpler as the pressure is reduced. Wallisch, in some experiments made at the Cavendish laboratory, found that the diminution in the value of pV - at low pressures is much more marked in some gases than in others, and in some gases he failed to detect it ; but it must be remembered that it is difficult to get measurements at pressures of only a few millimetres, as the amount of ioniza tion is so exceedingly small at such pressures that the quantities to be observed are hardly large enough to admit of accurate measurements by the methods available at higher pressures.The key to the behaviour of the negative ion is the fact that it begins by being an electron and does not unite with a molecule of the gas to form a normal ion until it has made a large number of collisions with the molecules of the gas through which it is pass ing. This number has been determined by Loeb (Phys. Rev., 17, p. 89, 1921 ; Phil. Mag., 43, p. 229, 1922), who finds that it is independent of the pressure of the gas but varies enormously from one gas to another ; thus in pure nitrogen, helium, argon and carbon monoxide in which this number is infinity the electrons never unite with the molecules ; in the number is about three millions, in air about 3o thousand, in oxygen three thousand and in chlorine less than two thousand. When in the electronic state the mobility is very high. Thus Franck found that the mobility of the negative ion in very pure argon was 206, while if 1% of oxygen was added the mobility fell to 1.7 and in pure helium Franck and Gehlhoff found that the mobility of the negative ion was 509. Haines ob tains still larger values for nitrogen and Loeb has shown that these high mobilities vary with the strength of the electric field. The life of the electron is much reduced by the presence of a trace of water vapour.

Most measurements of the mobilities of ions amount to meas uring the time taken by the ion to pass through a given length in the gas ; if the ion begins as an electron the mobility measured will be a mean value depending on the proportion of the time it is an electron to the time of transit. If the pressure is lowered the time in the electronic state is increased, since the number of col lisions the electron makes before leaving this state is unaltered by the change in pressure, while the time between each collision varies inversely as the pressure. The time of transit will be less at low pressures than at high, so that the proportion between the time in the electronic state and the time of transit will vary in versely as the square of the pressure. Thus the high mobility of the electron will produce much greater increase in the mobility at low pressures than at high, and will account for the effects observed by Langevin and Kovarik. It will also account for the fact that the rapid increase of the mobility at low pressures is much more marked in gases which have been carefully dried than in those which contain a trace of water vapour, and that these mobilities depend upon the strength of the electric field.

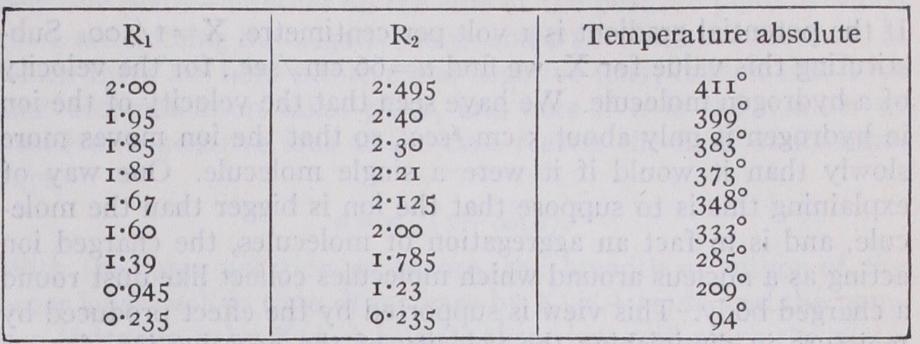

Effect of Temperature on the Velocity of the Ions.— Phillips (Proc. Roy. Soc., 1906, 78, p. 167) investigated, using Langevin's method, the velocities of the -}- and — ions through air at atmospheric pressure at temperatures ranging from that of boiling liquid air to 41i° C; and R2 are the velocities of the and — ions respectively when the force is a volt per centi metre.

We see that except in the case of the lowest temperature, that of liquid air, where there is a great drop in the velocity, the velocities of the ions are proportional to the absolute temperature ; since the pressure is constant this implies that at constant density the mobility is independent of the temperature. On the hypothesis of an ion of constant size we should, from the kinetic theory of gases, expect the velocity to be proportional to the square root of the absolute temperature, if the charge on the ion did not affect the number of collisions between the ion and the mole cules of the gas through which it is moving. If the collisions were brought about by the electrical attraction between the ions and the molecules, the velocity would be proportional to the absolute temperature. The mobility of ions at high temperatures such as those which occur in flames has been the subject of several experi ments. The first determination was made in 1899 by H. A. Wilson (Phil. Tran., A, 192, P. 499) who measured the mobility of positive ions in flames containing the vapour of alkali metals and found that it was 62 cm./sec. Andrade, in 1912 (Phil. Mag., 6, 23, 865) by a different method obtained the value 2.5 cm./sec. for sodium ions in a flame. H. A. Wilson, in a later investigation (Phil. Trans., A, 216, p. 63, 1916) came to the conclusion that his earlier values were much too high and estimated the true value as 1 cm./sec., which is of the same order as that obtained by Andrade.

The great effect of temperature is also shown in some experi ments of McClelland (Phil. Mag. [5], 46, p. 29) on the velocities of the ions in gases drawn from Bunsen flames and arcs ; he found that these depended upon the distance the gas had travelled from the flame. Thus, the velocity of the ions at a distance of 5.5 cm. from the Bunsen flame when the temperature was C was .23 cm./sec. for a volt per centimetre ; at a distance of r o cm. from the flame when the temperature was 16o° C the velocity was .21 cm./sec.; while at a distance of 14.5 cm. from the flame when the temperature was 105° C the velocity was only .04 cm./sec. If the temperature of the gas at this distance from the flame was raised by external means, the velocity of the ions increased.

We can derive some information as to the constitution of the ions by calculating the velocity with which a molecule of the gas would move in the electric field if it carried the same charge as the ion. From the theory of the diffusion of gases, as developed by Maxwell, we know that if the particles of a gas A are surrounded by a gas B, then, if the partial pressure of A is small, the velocity u with which its particles will move when acted upon by a force Xe is given by the equation Xe u= D (pl/Nl) where D represents the coefficient of inter-diffusion of A into B, and the number of particles of A per cubic centimetre when pressure due to A is pi. Let us calculate by this equation velocity with which a molecule of hydrogen would move hydrogen if it carried the charge carried by an ion, which we prove shortly to be equal to the charge carried by an atom hydrogen in the electrolysis of solutions. Since p1/N1 is pendent of the pressure, it is equal to II/N, where II is the pheric pressure and N the number of molecules in the cubic metre of gas at atmospheric pressure. Now Ne= 1.22 X if is measured in electrostatic units; II= o' and D in this case the coefficient of diffusion of hydrogen into itself, and is equal to If the potential gradient is i volt per centimetre, X=1/3o0. Sub stituting this value for X, we find u= 66 cm./sec., for the velocity of a hydrogen molecule. We have seen that the velocity of the ion in hydrogen is only about 5 cm./sec., so that the ion moves more slowly than it would if it were a single molecule. One way of explaining this is to suppose that the ion is bigger than the mole cule, and is in fact an aggregation of molecules, the charged ion acting as a nucleus around which molecules collect like dust round a charged body. This view is supported by the effect produced by moisture in diminishing the velocity of the negative ion, for, as C. T. R. Wilson (Phil. Trans. p. 289) has shown, moisture tends to collect round the ions, and condenses more easily on the negative than on the positive ion. In connection with the ve locities of ions in the gases drawn from flames, we find other instances which suggest that condensation takes place round the ions. An increase in the size of the system is not, however, the only way by which the velocity might fall below that calculated for the hydrogen molecule, for we must remember that the hydro gen molecule, whose coefficient of diffusion is 1.7, is not charged, while the ion is. The forces exerted by the ion on the other mole cules of hydrogen are not the same as those which would be exerted by a molecule of hydrogen, and as the coefficient of dif fusion depends on the forces between the molecules, the co efficient of diffusion of a charged molecule into hydrogen might be very different from that of an uncharged one.

Wellisch (loc. cit.) has shown that the effect of the charge on the ion is sufficient in many cases to explain the small velocity of the ions, even if there were no aggregation.

Mixture of Gases.—The ionization of a mixture of gases raises some very interesting questions. If we ionize a mixture of two very different gases, say hydrogen and carbonic acid, and investi gate the nature of the ions by measuring their velocities, the question arises, shall we find two kinds of positive and two kinds of negative ions moving with different velocities, as we should do if some of the positive ions were positively charged hydrogen molecules, while others were positively charged molecules of car bonic acid ; or shall we find only one velocity for the positive ions and one for the negative? Many experiments have been made on the velocity of ions in mixtures of two gases, but as yet no evi dence has been found of the existence of two different kinds of either positive or negative ions in such mixtures, although some of the methods for determining the velocities of the ions, espe cially Langevin's, ought to give evidence of this effect, if it existed. The experiments seem to show that the mobilities depend on the nature of the gas through which the ions move but not upon the nature of the ions themselves. Thus Blanc found that the mobility of an ion made in and driven through air was the same as that of an ion made in the air itself.

Grindley and Tyndall (Phil. Mag., 48, p. 711, 1924) show that the mobility through air of ions formed in and was practically the same as that of ordinary air ions. Erikson finds that argon, and H2 ions in air have the same mobility as air ions. Further, Rutherford has shown that the mobility of the heavy "recoil atoms" from radioactive sub stances, which have an atomic weight greater than 200 have in air the same mobility as air atoms. This is important because the radioactive nature of the ions was tested at the end of their path : so that this disposes of the attractive hypothesis that the charge keeps passing from one molecule to another so that how ever the ion may start, it is soon a molecule of the gas through which it is passing. Wellisch made very important experiments on mixed gases, e.g., mixtures of SO2 and and of ethyl ether and air, and found that he could only detect one type of positive and one of negative ions. The only exception to this result seems to be the fact discovered by Erikson that in air positive ions when they are "old," i.e., after some tenths of a second has elapsed since their formation, have only a mobility of about .7 of that of newly formed positive ions, he found no difference between young and old negative ions.

The most important results which have emerged from experi ments on the mobility of the ions are :- 1. The mobility of the ions, especially in the lighter gases, is much less than it would be if the ion consists of a single molecule having the same free path as an uncharged molecule.

2. The mobility of the ions depends only on the gas through which they move, so that though in a mixture of gases there may be ions of different kinds, all the ions of the same sign have the same mobility. An exception to this is the discovery by Erikson that aged ions have a smaller mobility than fresh ones.

3. In the lighter gases the mobility of the negative ions is greater than that of the positive.

4. The mobility of the negative ions is diminished by traces of the vapours of water and various alcohols.

5. For positive ions the product of the mobility and pressure is constant over a very wide range of pressure; for negative ions, however, the product at low pressure rapidly increases as the pressure diminishes.

6. Experiments with heavy ions from radioactive elements show that these have the normal mobility and retain their identity whilst in the electric field.

It is helpful to consider the various conditions which on the kinetic theory of gases would affect the mobility of the ions. The mobility of the ion is proportional to the coefficient of diffusion of the ion through the gas and this coefficient is equal to e is a numerical constant, X the free path of the iron through the gas; in-2 the masses of the ion and molecule respectively and h=RT/2 where T is the absolute temperature and R the gas con stant. First consider the effect of the electric charge on the free path, supposing for the moment that the mass of the ion is the same as that of a molecule. The attraction between an ion and a molecule will in consequence of the charge be greater than that between uncharged molecules ; the ion and the molecules will be dragged together and the free path of the ion less than that of the molecule. Thus X will be less for the ion than for the mole cule and the coefficient of diffusion less. If X' is the free path of the ion, X that of the uncharged molecule, w the work required to separate an ion from a molecule with which it is in contact, we can show that if the form between the ion and the molecule varies inversely as the fifth power of the distance when a is a numerical constant. We see from this expression that if we are to explain the slow diffusion of the ion by the charge alone, w must be large compared with RT, i.e., the work required to separate an ion from a molecule must be large compared with the kinetic energy of a molecule due to thermal agitation. It follows, however, from the principles of thermodynamics that in this case the ions will unite with the molecules and form aggre gates, and thus that any considerable diminution in the free path is inconsistent with the ions being monomolecular.

Let us turn now to the effect of mass upon the mobility of the ion; we see from the for the coefficient of diffusion that the mobility is proportional to Thus when the mass of the ion, is one, two, three—or an infinite number of times that of the molecule the mobilities are in the ratio 1.41, 1.22, 1.15--1. Though these differences are not very large they are much greater than is consistent with the experi mental fact that there is only one mobility for all positive and another for all negative in the same gas. While the mobility of a light ion through a heavy gas will be much greater than that of one formed by a molecule of this gas, thus from the formula the mobility of a hydrogen ion through methyl iodide would be six times that of a methyl iodide ion. We are forced to the conclusion that the ions cannot remain unaltered during their path through the gas, but must pass through various phases in which they have different mobilities, and that the mobility measured by the usual methods is an average value and not its value in any particular phase.

Rccombination.

Several methods enable us to deduce the co efficient of recombination of the ions when we know their veloci ties. Perhaps the simplest of these consists in determining the relation between the current passing between two parallel plates immersed in ionized gas and the potential difference between the plates. For let q be the amount of ionization, i.e., the number of ions produced per second per unit volume of the gas, A the area of one of the plates, and d the distance between them ; then if the ionization is constant through the volume, the number of ions of one sign produced per second in the gas is qAd. Now if i is the current per unit area of the plate and e the charge on an ion, iA/e ions of each sign are driven out of the gas by the current each second. In addition to this source of loss of ions there is the loss due to the recombination ; if n is the number of positive or nega tive ions per unit volume, then the number which recombine per second is ant per cubic centimetre, and if n is constant through the volume of the gas, as will approximately be the case if the current through the gas is only a small fraction of the saturation current, the number of ions which disappear per second through recombination is Hence, since when the gas is in a steady state the number of ions produced must be equal to the number which disappear, we have qAd = q= i/ed + If and are the velocities with which the positive and tive ions move, and are respectively the quantities positive electricity passing in one direction through unit area the gas per second, and of negative in the opposite direction, If X is the electric force acting on the gas, and the velocities of the positive and negative ions under unit force, ; hence and we have q = i + at*" ed But qed is the saturation current per unit area of the plate; calling this I, we have dais I — or will broaden out and will consist of three portions, one in which there are nothing but positive ions,—this is on the side of the negative plate,—another on the side of the positive plate in which there are nothing but negative ions, and a portion between these in which there are both positive and negative ions; it is in this layer that recombination takes place, and here if n is the number of positive or negative ions at the time t after the flash of Röntgen rays, n= With the same notation as before, the breadth of either of the outer layers will in time dt increase by X and the num ber of ions in it by X these ions will reach the plate, the outer layers will receive fresh ions until the middle one dis appears, which it will do after a time l/X where 1 is the thickness of the slab ab of ionized gas; hence N, the number of ions reaching either plate, is given by the equation N _ Cllxck1+k2)noX (ki+k2) _ X (k1+k2) l0 1-}- n t a k2) l I o If Q is the charge received by the plate, Q=Ne= X log (I+ / 47re 47rX where = is the charge received by the plate when the electric force is large enough to prevent recombination, and e= We can from this result deduce the value of e and hence the value of a when k1+k2 is known.

Distribution of Electric Force When a Current Is Passing

Through an Ionized Gas.—Let the two plates be at right angles to the axis of x; then we may suppose that between the plates the electric intensity X is everywhere parallel to the axis of x. The velocities of both the positive and negative ions are assumed to be proportional to X. Let represent these velocities respectively; let be respectively the number of positive and negative ions per unit volume at a point fixed by the co-ordinate x; let q be the number of positive or negative ions produced in unit time per unit volume at this point ; and let the number of ions which recombine in unit volume in unit time be ; then if e is the charge on the ion, the volume density of the electrifi cation is e, hence dX dx = If I is the current through unit area of the gas and if we neglect any diffusion except that caused by the electric field, Hence if we determine corresponding values of X and i we can deduce the value of a/e if we also know The value of I is easily determined, as it is the current when X is very large. The preceding result only applies when i is small compared with I, as it is only in this case that the values of n and X are uniform throughout the volume of the gas. Another method which answers the same purpose is due to Langevin (Ann. Claim. Phys., 1903, 28, p. 289) ; it is as follows. Let A and B be two parallel planes im mersed in a gas, and let a slab of the gas bounded by the planes a, b parallel to A and B be ionized by an instantaneous flash of Röntgen rays. If A and B are at different electric potentials, then all the positive ions produced by the rays will be attracted by the negative plate and all the negative ions by the positive, if the electric field were exceedingly large they would reach these plates before they had time to recombine, so that each plate would re ceive ions if the flash of Röntgen rays produced positive and negative ions. With weaker fields the number of ions re ceived by the plates will be less as some of them will recombine before they can reach the plates. We can find the number of ions which reach the plates in this case in the following way :—In consequence of the movement of the ions the slab of ionized gas and from these equations we can, if we know the distribution of electric intensity between the plates, calculate the number of positive and negative ions.

In a steady state the number of positive and negative ions in

unit volume at a given place remains constant, hence neglecting the loss by diffusion, we have an equation which is very useful, because it enables us, if know the distribution of to find whether at any point in the gas the ionization is greater or less than the recombination of the ions. We see that q— which is the excess of ionization over recombination, is proportional to Thus when the ioni zation exceeds the recombination, i.e., when is positive, the curve for is convex to the axis of x, while when the recombi nation exceeds the ionization the curve for will be concave to the axis of x. Thus, for example, fig. 7 represents the curve for observed by Graham (Wied. Ann. 64, P. 49) in a tube through which a steady current is passing. Interpreting it by equation (7), we infer that ionization was much in excess of recombination at A and B, slightly so along C, while along D the recombination exceeded the ionization. Substi tuting in equation (7) the values of given in (3), (4), we get investigation that if and X2 are the values of X at the positive and negative plates respectively, and the value of X outside the layer, where Langevin found that for air at a pressure of 152 mm. at 375 mm. and at 76o mm. E=0•27. Thus at fairly low pressures i/E is large, and we have approxi mately Therefore or the force at the positive plate is to that at the negative plate as the velocity of the positive ion is to that of the negative ion. Thus the force at the negative plate is greater than that at the positive. The falls of potential V1, V2 at the two layers when 1/E is large can be shown to be given by the equations This equation can be solved (see Thomson, Phil. Mag. xlvii. p. 253), when q is constant and From the solution it ap pears that if be the value of x close to one of the plates, and the value midway between them.

2(

i-13) where = 8 Since e = 4. 7 7 X a = I .6 X i X I o 6, and k' for air at at mospheric pressure = 5 2o, (3 is about 3.9 for air at atmospheric pressure and it becomes much greater at lower pressures.Thus is always greater than unity, and the value of the ratio increases from unity to infinity as (3 increases from zero to infinity. As j3 does not involve either q or I, the ratio of to is independent of the strength of the current and of the intens ity of the ionization.

No general solution of equation (8) has been found when is not equal to but we can get an approximation to the solution when q is constant. The equations (1), (2), (3), (4) are satisfied by the values k1n1Xe= k1 I, k1+k2 = k2 I, ki±k2 X= I • k ql ( -{- 2) These solutions cannot, however, hold right up to the surface of the plates, for across each unit of area, at a point P, positive ions pass in unit time, and these must all come from the region between P and the positive plate. If X is the distance of P from this plate, this region cannot furnish more than qX positive ions, and only this number if there are no recombinations. Hence the solution cannot hold when qX is less than or where X is less than Similarly the solution cannot hold nearer to the negative plate than the distance The force in these layers will be greater than that in the middle of the gas, and so the loss of ions by recombination will be smaller in comparison with the loss due to the removal of the ions by the current. If we assume that in these layers the loss of ions by recombination can be neglected, we can by the method of the next article find an expression for the value of the electric force at any point in the layer. This, in conjunction with the value Xo= (a I for the gas outside the layer, will give the q e(ki-l-k2)-l-- k2) value of X at any point between the plates. It follows from this hence so that the potential falls at the electrodes are proportional to the squares of the velocities of the ions. The change in potential across the layers is proportional to the square of the current, while the potential change between the layers is proportional to the current, the total potential difference between the plates is the sum of these changes, hence the relation between V and i will be of the form V = Aid-BP.

Mie