Andrassy Note

ANDRASSY NOTE), complicated by the massacre of European con suls at Salonika (May 1876) and the "Bulgarian atrocities." (See BULGARIA.) The Eastern Question (q.v.) thus was opened again in critical circumstances for the Ottoman empire. Alexander had already consulted with Austria at the interview of Reichstadt, July 8, 1876. Francis Joseph wished to obtain compensation for the loss of his territories in Italy by acquisitions in the Balkan peninsula; he accepted a convention allowing him compensation in Bosnia, if territorial changes took place. No European Government was prepared again to trust the promises of reform made by the Turks; control by European agents was required. Disraeli, though harassed by the agitation of Gladstone, adhered to the traditional British policy in favour of the Ottoman empire and sent a fleet to the neighbourhood of Constantinople ; Alexander mobilized and forced the Turks, who had been victorious in Serbia, to grant an armistice; and England also accepted a conference of the ambas sadors of the great Powers at Constantinople, which drew up a scheme of reforms. This intervention was paralysed by the pro mulgation of the Turkish Constitution planned by Midhat Pasha, the Turks declaring that they were contrary to the Constitution.

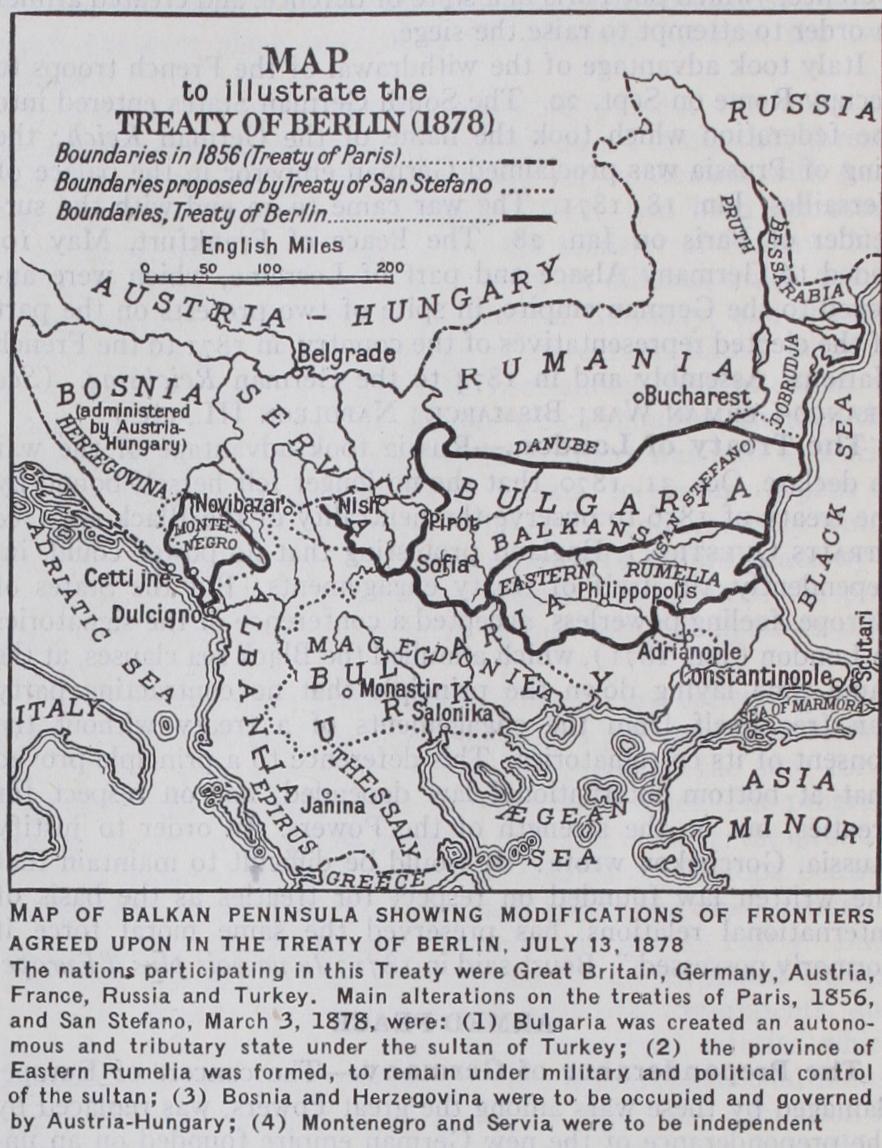

Alexander reaffirmed his agreement with Austria by a treaty of April 1877 and began the war. England alone protested, but added that she would only interfere to safeguard "her vital in terests," the Suez canal, the Straits, Constantinople. Alexander wished to limit himself to a war north of the Balkans, but was led into an invasion which took the Russian armies within strik ing distance of Constantinople, when the sultan asked for peace. The British Government was divided; the queen wished for war; Derby wanted peace ; Disraeli contented himself with warlike manifestations in order to appease the excited Londoners, and refused to withdraw the British fleet. The grand duke Nicholas replied by advancing his headquarters to the suburbs of Constan tinople. There the Russian plenipotentiary, Ignatiev, imposed on the sultan on March 3, the Treaty of San Stefano, the latter ceding all the land occupied by the Bulgarian population in order to allow the formation of a "big Bulgaria" under the protection of Russia.

The Congress of Berlin, 1878.

Bismarck demanded that the treaty should be revised by the great Powers. Gorchakov, who did not wish the creation of a "big Bulgaria" to be called in ques tion, proposed a conference at Berlin, in which each State should reserve full liberty of action ; England demanded that the whole treaty should be submitted for revision. Alexander was short of money and needed peace ; he yielded and sent Shuvalov on a special mission to Bismarck, and thence to England where he concluded a secret convention (May 3o). Russia undertook to submit "the whole contents of the treaty" to a European congress. England concluded with the sultan a secret treaty (June 4) under taking to defend the Ottoman empire in Asia Minor in exchange for the occupation of Cyprus. Bismarck had declared in the Reichstag that he merely wished to play the part of "an honest broker." The congress held at Berlin under his presidency was a tribute to the dominant position held by Germany (see BERLIN, CONGRESS OF). It imposed upon the sultan an Austrian occupa tion of Bosnia, and destroyed "big Bulgaria" by cutting it into three pieces. England made public the treaty which ceded Cyprus to her. Waddington, the French minister, protested; in order to appease him Salisbury made some allusion to Tunis. The three tributary Christian principalities of the sultan in Europe were declared to be sovereign States. Greece was promised a rectifica tion of frontier, which did not take place until 1881.

The Austro-German Alliance, 1879.

The Russians did not receive an adequate reward for the sacrifices they had made in comparison with Austria, which, without having gone to war at all, became a Balkan power and a rival of Russia in the Balkans. Alexander recalled the fact that in 1871 William had written to him that Germany owed to him the happy issue of the war and had signed himself "Your ever grateful friend" ; Gorchakov wrote to his ambassador at Vienna, Feb. 4, 1879, "It is unnecessary to say that in our eyes the alliance of the three emperors has been broken by the conduct of our two allies." William himself re mained outside the conflict, and had a secret interview with Alex ander (Sept. 3, 1878).Bismarck made overtures to Austria; giving as his reason for so doing that he f eared an agreement between Russia and Aus tria, and wished to prevent it by a close alliance with one of them; he preferred Austria because she would be willing to allow Germany to be the predominant partner, and the matter was con cluded by a secret treaty in the form of an alliance for the main tenance of peace and mutual defence, should one of the two be attacked by Russia, while if the attack came from any other power, they only engaged themselves to maintain a benevolent neutrality. William maintained his friendship with Alexander, and insisted that he should be informed of the treaty. He had several personal interviews with him, and Alexander drank to the health of "his best friend William" in March 1880. Bismarck, not wishing for a permanent misunderstanding entered into nego tiations with the Russian Government for a defensive alliance.

The Triple Alliance, 1882.

Ill-feeling against Germany showed itself in Russia in newspaper articles favourable to France, while the idea of a Franco-Russian entente took hold of public opinion in France, which hoped to find a protector against Ger many. Italy was divided between opposition to France, where the Catholics upheld the temporal power of the pope, and enmity towards Austria, the possessor of Italia irredenta. From the time that the republican party came into power the Italian Government drew nearer to France; and allowed the "irredentists" to make demonstrations against Austria. The establishment of a French protectorate over Tunis, 1880, made an abrupt change in Italian sentiment. The Italians held that they themselves had rights over Tunis, as the near neighbour of Sicily, where many Italians lived, and the Italian Government had protested in advance against operations in Tunis. Gambetta and Waddington had as sured them that France would not undertake any course of action without coming to a preliminary agreement. Public opinion in Italy became hostile to France. The Government drew closer to Austria and King Humbert paid a visit to the emperor (Oct. 1881) during which he asked to be admitted into the defensive alliance of the two monarchies. After long negotiations Italy con cluded two secret treaties of defensive alliance with Germany and Austria. If Italy were attacked by France, her allies promised to support her; and Italy undertook to support her allies in a war against two Powers. A special protocol (May 20, 1882) declared that the treaty could in no circumstances be directed against Eng land. The Triple Alliance therefore appeared as a guarantee for the peace of Europe and the maintenance of the status quo, at the same time preserving the traditional friendship between Italy and Great Britain. Rumania adhered to it by a secret treaty with Austria, the personal work of King Charles, which he communi cated only to one minister (1883) and to which Germany and Italy later acceded by engaging to defend Rumania. The Triple Alliance was reduced in practice to a defensive agreement between the central European powers against the warlike intentions attrib uted to their neighbours, France and Russia. But it reinforced the predominance of Germany, the most powerful of the partners, and gave the impression of a compact coalition in the centre of Europe against the isolated powers outside. The Concert of Europe was replaced by the hegemony of the German empire.Alexander III., emperor of Russia since 1881, did not love the Germans, but wished for the maintenance of peace. He gave the direction of foreign affairs to a Baltic German, de Giers, who was in favour of an entente with Germany. In reply to a telegram of congratulation he called William "this venerable friend to whom we are united by common ties of deep affection." Bismarck also hoped to avoid a breach with Russia. A secret treaty was con cluded at Berlin for three years (June 11, 1881) between the "three courts" of Austria, Germany and Russia, which bound them to work in concert in matters relating to the Balkans. This treaty was kept so secret that before the publication of the Aus trian secret archives it was believed that it was not concluded until 1884. At its renewal in 1884 the agreement was shown to the world by an interview of the three emperors at Skiernewicze, Sept. 1884. This treaty, which Bismarck called the "re-insurance treaty," combined the Triple Alliance with the Alliance of the three emperors. England had entered into conflict with France, who was creating a colonial empire in Africa and Indo-China, over Egypt in 1882, and with Russia over Afghanistan in 1884. Bismarck profited by these rivalries to improve the relations of Germany with the rival powers. He encouraged French enterprise in order to keep her attention occupied outside Europe. He said to the French ambassador : "I wish to see you come to the point when you will forgive Sedan as you have forgiven Waterloo" ; he even suggested an alliance "to establish a kind of maritime balance of power." He caused to be held the Conference of Berlin, which settled the rules for the occupation of lands outside Europe (1884) ; and when the Eastern Question was re-opened by the union of Rumelia and Bulgaria (see BULGARIA) in 1885, he sup ported Alexander in his refusal to recognize the union. Austria encouraged her protege Milan, king of Serbia to embark on war with Bulgaria. On the side of France relations were strained by the manifestations of Gen. Boulanger (q.v.) and his followers. Frontier incidents in 1887 irritated public opinion; France and Germany both talked of war ; and Bismarck increased the effec tives of the army and guaranteed Germany on the side of Russia by renewing in 1887 the re-insurance treaty. The Triple Alliance treaties, originally concluded for five years were renewed and completed. Italy complained, in the words of the minister Robi lant, of being "always left out in the ante-room." She obtained from Austria the assurance that she would not modify the ter ritorial status quo in the East except on the principle "of reciprocal compensation for every advantage" obtained by the one or the other (May 1 o, 1887) . The British Government accepted the suggestion of Italy to act in concert for the maintenance of the existing state of affairs in the Mediterranean and the adjoining seas.

The Franco-Russian Entente.

Bismarck had not been able to prevent the entente weakening between Germany and Russia. The idea of a rapprochement with France grew more popular in Russia, starting in the realm of finance ; the German Government retaliated by forbidding the Reichsbank to accept as collateral the Russian State funds which were, however, accepted with alac rity by the Paris Bourse. Alexander hesitated for some time to enter into close relations with France, and had a long interview at Berlin (Nov. 1887) with Bismarck, whose fall (189o) changed the policy of Germany, while the establishment of a stable min istry in France broke down one of Alexander's objections to a rapprochement. William II. had taken over the direction of Ger man policy. He refused to renew the treaty of 1887 with Russia and tried to come to an agreement with the western States. He entered into cordial relations with the Salisbury ministry and con cluded a treaty whereby England gave up Heligoland in exchange for concession in East Africa (189o) . He made advances to France, and his mother came to Paris to prepare the way for a rapprochement on the neutral ground of art. But the visit of the empress-dowager led to demonstrations on the part of Parisian nationalists and made relations w orse with France (Feb. 1891) . French opinion, uneasy because France was isolated in face of Germany, ardently desired to obtain the protection of Russia, whose military power she exaggerated, and Alexander at length allowed himself to be drawn into a permanent understanding. His resolution was made public by the reception of the French fleet at Kronstadt (Aug. 1891) . The understanding was not completed in the form of a treaty; the tsar insisted on keeping it secret, and President Carnot could not guarantee that he would not be obliged to present it to the chambers. The two Governments con sidering that the maintenance of peace was bound up with the bal ance of power in Europe engaged themselves to act in concert on all questions which jeopardized the cause of peace, and if peace was menaced by the initiative of the Triple Alliance to use their forces simultaneously. The French Government insisted on the conclusion of a military convention. This plan was accepted by Russia and signed by the chiefs of the general staffs of the two countries in July 1892; it arranged, in case of a "defensive war," a simultaneous mobilization to be directed against Germany. Alexander left the scheme in suspense for a year ; then he indicated his decision by the dispatch of the Russian fleet to France (Oct. 1893) and a telegram to the president. The convention was "defi nitely adopted" by the exchange of letters in Dec. 1893. This purely defensive agreement which is called "the Franco-Russian Alliance" did nothing definite but maintain the state of things established by the treaty of Frankfurt, which was also the object of the Triple Alliance ; but it reassured French public opinion and it gave Europe the impression that European balance, broken by the Triple Alliance, had been restored.

Policy of William II.

Bismarck, preoccupied with the main tenance of German supremacy in Europe, had been little inter ested in the expansion of Germany in the rest of the globe. This old man's policy did not satisfy William, who was young, anxious to shine in the world, and to use his power. The population of Germany was growing rapidly, as were also her industries, her trade and her riches; her commercial agents, supported by her banks, sought outlets for her products throughout the whole world; her mercantile marine carried the German flag in all seas. The Germans were aware of their growing power and found themselves restricted in Europe; and they aired their need for expansion in formulas—Mitteleuropa (the union of all the coun tries of Central Europe under the economic direction of Ger many) Drang nach Osten (expansion in the Balkan and Moham medan East) Colonialpolitik (the creation of colonies outside Europe), and particularly in the creation of a navy to support German commerce and raise German prestige, all of which objects found an enthusiastic leader in the Emperor, who had, from his youth, been devoted to navigation and travel. It is this policy which has received the title of Weltpolitik. Weltpolitik brought Germany into rivalry with the two great colonial powers, England and France, for both had forestalled her by occupying almost all the available countries, and Great Britain was uncontested mis tress of the seas. Thus the balance of power was upset by this new policy of expansion in the rest of the world.Since 1889, when he had paid a visit to the sultan at Constan tinople, William II. had devoted himself to promoting German influence in Turkey. A permanent mission of German officers directed in Constantinople the technical instruction of the Turkish army. Abd-ul-Hamid, feeling himself protected by Germany, freed himself from the obligations into which Turkey had entered in 1878 under the British guarantee and massacred his Armenian subjects in Asia Minor and at Constantinople (1894-96).

Nicholas II. who had ascended the Russian throne in 1894 and who lacked strength of character, fell under the influence of Wil liam II. and entered into an intimate correspondence with him which was published after the Russian Revolution. William wished to take advantage of this to bring together under his in fluence the two opposing groups of States into which Europe was divided—the Triple Alliance and the Franco-Russian Alliance. He induced Nicholas to intervene in the Far East where Japan had just defeated China, and out of regard for the tsar, the French Government joined with Germany and Russia to enforce the annulment of the treaty concluded by Japan with China (1895) . The tsar then induced the French Government to add French ships to the foreign squadrons attending the celebration of the official opening of the Kiel canal. Further, William sought to take advantage of a conflict which arose between England and France over the district of the upper Nile, and since 1894 had suggested to France that she should make a united protest with him against the treaty concluded between Great Britain and the Congo Free State. After the Jameson raid on the Transvaal (q.v.) and the dispatch of his famous telegram to President Kruger, the kaiser, with a view to limiting "the insatiable appetite of Eng land," proposed to France a treaty by which Germany and France should mutually guarantee each other's territories. But the French Government repelled the suggestion, seeing that would have been interpreted as an assent to the annexation of Alsace; for French public opinion, although it was strongly opposed to war, had never accepted the annexation of Alsace which had been carried out against the wishes of the inhabitants.

The Cretan massacres of 1897 were stopped by the landing of marines from the ships of the European States with the exception of Germany who refused to take part in an intervention that resulted in the establishment of an autonomous Christian Govern ment in Crete. The war which followed between Greece and Turkey rapidly ended in a resounding victory for the Turkish army whose success was ascribed to the work of its German in structors. The kaiser undertook a triumphal journey in Syria in order to reveal to the world the extent of German influence in the East, and at Damascus announced himself as "the friend of 300,000,00o Mohammedans" (1898).

Owing to her preoccupations in the Far East Russia seemed to have lost interest in the Balkan peninsula; Austria took advan tage of this to establish her preponderance there. In May Austria concluded an understanding with Russia for the purpose of maintaining the Balkan status quo, Russia reserving for further examination the future projects of Austria in Bosnia and Al bania ; in 1896 the secret treaty between Austria and Rumania was renewed, and about the same time Serbia, which was governed by the Obrenovitch dynasty, delivered up the kingdom to Austrian financiers and behaved as the protege of Austria. It became the habit of Austrian diplomacy to treat Serbia more as an Austrian province than as a sovereign State, and it was this conception that underlay the Austrian ultimatum in 1914. The prince of Bulgaria, Ferdinand of Coburg, a Catholic, and formerly an officer in the Austrian army, had reconciled himself with the tsar by inviting him to be godfather to his son Boris, but at the same time his relations with the Viennese Government were more intimate than with Russia. Austria and Russia were moving towards a partition of the Balkan peninsula into two spheres of influence ; and the Russian general Kuropatkin, who was sent on a special mission to Vienna, even proposed that a line should be drawn from north to south and that the Russian sphere of influence should lie to the east and the Austrian to the west. In reality the whole peninsula had become an Austrian sphere of influence.

Armed Peace.

Russia simultaneously made known her entente with France by an exchange of visits between the imperial family and the president of the republic, and her understanding with Germany by an exchange of visits between the tsar and the kaiser (1896-97). Italy announced that she interpreted alliance as a "pacific act which permitted to the allies the most friendly rela tions with the other Powers." The Italian crown prince married the daughter of the prince of Montenegro, who was a protege of Russia, and Italy signed with France an agreement concerning Tunis and her fleet collaborated with the French fleet in Crete. All these alliances and rapprochesnents seemed to assure peace in Europe ; and all the governments protested their devotion to peace but not one had any confidence in the assurances of the others, seeing in the pacific declarations of his neighbour only a cloak to conceal offensive designs. No nation felt secure. The war of 187o had revealed that it was not enough to wait until war began in order to place armies in motion. Mobilization had be come so rapid and the advantage to be gained from taking the offensive so overwhelming that every Government felt it its duty to secure the advantage of the offensive by keeping its army always ready for an immediate war. Thus the effective strength of the armies in time of peace came to equal their former strength on a war footing. Moreover, the rapid progress that had been made in military technique compelled each State, in order not to be inferior to the others, to renew constantly its equipment and artillery and to increase its fighting strength. Thus the military budgets rose swiftly higher and higher. The efforts of the Inter national. League of Peace on behalf of arbitration (q.v.) produced no effect on public opinion except in the United States and Scandi navia; the great Powers remained indifferent. Europe lived under "an armed peace," or peace with all the military and financial burdens common to war, and lacking all sense of security.

The Hague Conference 1899.

Nicholas II., who had been impressed by War, the work of a Russian financier, J. von Bloch, and whose Government was struggling with the military expenses of the operations in Asia, sought to reduce expenditure by obtain ing a concerted action among the powers for a reduction of arma ments. Russia invited all the States to send representatives to a Conference at The Hague to consider the means of effecting this, and the project was welcomed by public opinion which gave The Hague Conference (q.v.) the name of "Peace Conference." It did not obtain any limitation of armaments, but it secured three international conventions on the conduct of war on land and sea, and on voluntary arbitration between States. A permanent Court of International Justice was established at The Hague and the principle was propounded that any State had the right to offer its mediation or good offices to States in disagreement with one an other. For the first time an international assembly representative of the governments of the world, met to discuss an abstract ques tion of general interest, and in a modest form they created the first permanent international institution for the purpose, no longer merely of regulating the re-distribution of territory in accordance with the balance of power, but also of making an end to disputes by the application of international law. It was the embryo of the association of States which the French delegate, Leon Bour geois, had already named a "Society." Change in British Policy.—Great Britain had for long main tained herself in a position of "splendid isolation." Her relations with France had been strained by conflicts that arose between officers and agents of the two countries in all parts of the world in which they were rivals; in Indo-China where the conflict with Siam was only settled by the treaty of 1896; in western Africa over the Niger (see AFRICA) ; and above all in Egypt where the Marchand expedition on reaching Fashoda in 1898 came into conflict with the British. The tension relaxed when the coalition of the Left came into power in France, and Delcasse, who was foreign minister for four years, worked to achieve an understand ing with England. With Germany, on the other hand, British re lations became strained when William in agreement with his min ister of marine, Admiral von Tirpitz, sought to create a navy, and the Reichstag voted credits to carry out a naval programme intended to double the strength of the German fleet (19o0).The second Boer war brought the isolation of England into sharp relief. Germany, Russia and France planned a common in tervention to end the war, but did not dare to act. William II. laid aside his former policy, sought to achieve an understanding with England by forbidding German officers to take service with the Boers, and by paying a visit to London where he had an in terview with Joseph Chamberlain, then secretary of State for the Colonies. In a speech at Leicester Chamberlain adopted a popular theory and proposed a "new Triple Alliance" between the three Teutonic peoples—Germans, English and Americans (Nov. and William II. refused to receive President Kruger when he came to Europe to ask help. But the German press remained hos tile to England. The new Chancellor, Prince Billow, a disciple of Bismarck, believed that an understanding with England would prevent Germany rom creating an independent navy, and pre ferred to retain his liberty to build a fleet against the British fleet, merely taking care to avoid a rupture during "the danger ous period of construction." Baron von Holstein, who was di rector of political affairs in the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, ex ercised an occult influence on the policy of Germany and dis trusted England. British policy was based upon the principle that Great Britain, seeing that she was unable to feed her population except with the help of imports, must of necessity maintain her maritime supremacy; and this was the meaning of the formula of the "two power standard." The British Government never feared an invasion of England by the German army, a prospect that inspired popular anxiety in England ; but it did fear that in a grave conflict with Germany the existence of a powerful Ger man fleet might compel England to give way. The memorandum which was presented with the estimates for the construction of the German fleet said that this fleet should be so strong that "even for the greatest of all maritime powers, a war with it would imply the imperilment of its own supremacy." But by becoming a great naval Power Germany inevitably risked coming into con flict with Great Britain in all parts of the world in which British commerce and policy were deeply involved—Egypt, Persia, India —and should Germany be able to obtain the alliance of other maritime Powers the resulting coalition would threaten the mari time supremacy on which the British empire depended.

English supporters of a German alliance warned the German Government that England did not desire to remain isolated, and that if she was unable to obtain the alliance of Germany, she must seek other allies. But the Germans did not believe in the possibility of a real friendship between "the whale and the bear" (England and Russia) and they feared that England would use Germany for a war against Russia from which England would derive the profit. Abandoning the idea of a German alliance, Eng land allied herself with Japan in 1902 (see ANGLO-JAPANESE