Animal Equilibrium

EQUILIBRIUM, ANIMAL. If we had to construct a machine to imitate a man one of our many difficulties would be to arrange it so as to walk and run, or even to stand upright, without falling over. We should have to contrive so that every movement of the limbs would call into play some compensating device which would redress the balance and keep it within the narrow limits imposed by the small base of support. The prob lem would be easier if our machine were to imitate a f our-f ooted animal, but it would still be difficult enough. One of the most interesting topics of present-day physiology is that concerned with the equilibrium of the body at rest and in motion, and con siderable advances have been made in the past few years.

To maintain the normal posture of the body constant muscular activity is necessary ; this must be controlled by the central nerv ous system, and the central nervous system must be directed by the messages received from the various sense organs which indi cate what kind of adjustment is necessary and how well it is succeeding. An analysis of the mechanism of equilibrium must therefore begin with the sense organs which guide it. These are the labyrinth organs in the internal ear, the sense organs in the muscles, tendons, joints and skin, and, in many animals, the eyes.

In man it is obvious that the eyes play an important part in balancing the body. We can see the relation of our body to the ground and if we shut our eyes it is much more difficult to stand upright with the feet close together. Anyone who experiences a steeply banked turn in an aeroplane for the first time will realize that the eyes are not the only sense organ concerned in giving us a frame of reference in space. The horizon seems to tilt and the aeroplane to remain level owing to the effect of centrifugal force on the labyrinth organs which make us feel that "up" and "down" are still where they were bef ore in relation to our seat in the aeroplane. In man, therefore, the eyes can be overruled by the labyrinths; but it is a remarkable fact that in many animals the eyes seem to give no information at all as to the position of the animal in space. Magnus and his co-workers at Utrecht have shown that an animal suspended in any position above the ground has a tendency to turn the head into the normal position, i.e., the position it would take up if the animal were standing on the level. In monkeys, cats and dogs, as in man, the "righting" of the head in space is dependent on messages received from the eyes as well as from the labyrinth organs. The righting will still take place of ter the destruction of the labyrinths, provided that the animal can see, but if it is blindfolded the head hangs limply and no attempt is made to raise it. But in rabbits and guinea pigs, the destruction of the labyrinths stops the righting reaction com pletely and the eyes play no part in it. In fact the optical right ing reactions are only present when the eyes and their nervous connections in the brain are highly developed.

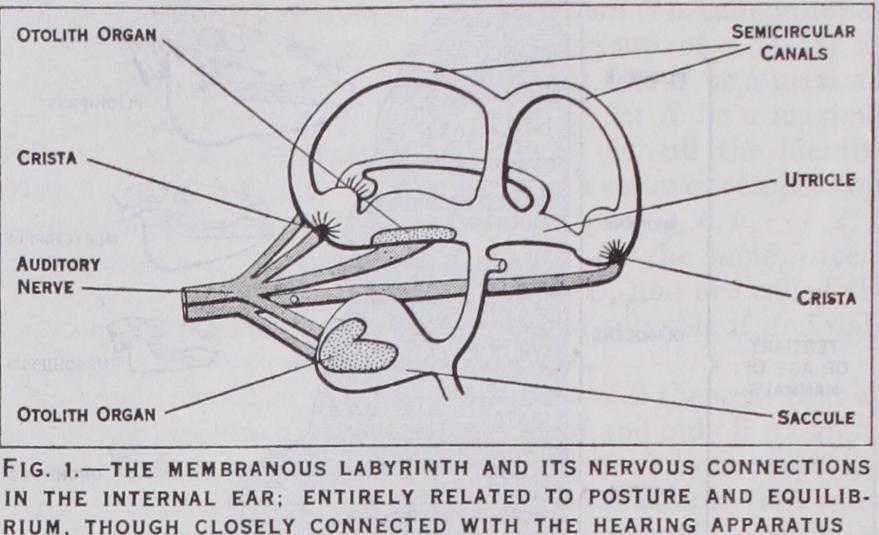

The reactions due to the labyrinth organs are found in all the vertebrates, and the labyrinth is the one sense organ entirely concerned with posture and equilibrium. It consists of a series of membranous chambers and tubes immersed in fluid and contained in the bony cavity of the inner ear. In mammals the labyrinth is closely joined to the cochlea, the sense organ responsive to sound, but the two are supplied by separate branches of the viii. cranial nerve and the branches have separate connections in the brain stem. The membranous part of the labyrinth is composed of two small bags, the saccule and the utricle, and three semi circular canals which open into it and lie in three planes at right angles to one another (see fig. I) . The nerve fibres which sup ply the labyrinth (the vestibular division of the viii. nerve) end in close connection with a number of cells furnished with hair like projections and grouped together to form the two otolith organs in the saccule and utricle and the three cristae of the semi circular canals. In the otolith organs the hairs are embedded in a gelatinous substance containing small masses of calcium carbonate called otoliths. The hairs of the cristae are much longer and the gelatinous substance round them has no otoliths.

The action of the different parts of the labyrinth is still far from clear, though there is no doubt about the action of the organ as a whole. When the animal is at rest the labyrinth signals the direction of the earth's gravitational attraction ; when the animal is in motion it signals any change in acceleration due either to rotation or to movement in a straight line. If the labyrinths are destroyed on both sides, an animal without optical righting re flexes hangs limply when held in the air instead of struggling to right itself. Other sense organs can come into play when the body is in contact with the ground and the animal can then move from an abnormal into the normal posture because the abnormal distribution of pressure on the body surface gives the necessary information to the nervous system. In man equilibrium can be maintained without the labyrinth organs by the aid of the eyes and the sense organs of the muscles and body surface, and it is so maintained in congenital deaf mutes whose inner ear is imper fectly developed. But a man with defective labyrinths if blind folded and placed in water so as to equalize the pressure on the body, becomes completely helpless and has no longer any notion of the position of his body in space.

The ceaseless activity of the labyrinth and its overwhelming influence on the posture of the body is shown most clearly from the effects of destruction of one labyrinth leaving the other in tact. Bilateral destruction will not produce a serious disturbance of equilibrium unless the other sense organs (eyes, body wall, muscles, etc.) are out of action as well, but unilateral destruction allows the nervous system to be subjected to the labyrinthine sti muli from one side only and the result is a gross distortion of posture of ten combined with violent rolling movements of the body about its long axis. The sudden convulsive attacks of Meniere's disease are due to the same lack of balance between the two labyrinths in patients with disease of the inner ear.

It is generally supposed that the labyrinth acts by signalling (a) the pull of gravity on the otoliths of the saccule and utricle and (b) the movement of fluid past the cristae of the semi-cir cular canals caused by angular or linear acceleration of the head, the otolith organs being responsible for the steady posture of the animal at rest and the semi-circular canals for the balancing of the body in movement. This view was based on the earlier work of Breuer and Mach, and until recently it seemed to be confirmed, for mammals at least, by the experiments of Magnus and de Kleijn in which the otolith organs were destroyed without injury to the semi-circular canals. But the latest results tend to show that it is not possible to draw a clear distinction between the static and dynamic apparatus of the labyrinth, for there is evi dence of preservation of the static reactions in mammals after the otolith organs have been destroyed. This agrees with the observations of Maxwell in fish, where either otoliths or semi circular canals can be put out of action without producing any marked disturbance of equilibrium either at rest or in motion. For the present, therefore, we must be content to take the laby rinth as a whole without attempting to draw a sharp distinction between the functions of the otoliths and the canals.

Apart from the eyes and the labyrinths, the nervous system is continually receiving messages from the sense organs in the mus cles, tendons and joints and from those responsive to pressure and touch. The former group signal the position of the head and limbs in relation to the body and the amount of tension each muscle is exerting. The latter show where the weight is resting.

The nervous mechanism for co-ordinating these sensory mes sages is centered in the brain stem just below the cerebral hemis pheres. Both the cerebrum and the cerebellum may be removed without interfering with the balancing power of an animal as high in the scale as a cat or dog, but no trace of any posture, normal or abnormal, remains if the brain stem is destroyed down to the level of the medulla (see fig. 2) . If only the upper part of the brain stem is destroyed, the nervous mechanism is seriously damaged, but it is still able to produce something like a co ordinated posture. The limbs are rigidly extended and the trunk arched backwards so that the animal would be in something like its normal standing position if it were placed on its feet. This condition is known as "decerebrate rigidity" and Sherrington's investigation of it and appreciation of its meaning has been the starting point of the whole analysis of the postural mechanism carried out recently by Magnus.

In decerebrate rigidity the only postural reactions which re main are of no use to the animal. The extended position of the limbs is retained for hours, but the animal cannot stand by itself and makes no attempt to change its position if placed on its back or side. Yet there is no doubt that the posture of decerebrate rigidity is brought about by the same nervous mechanism (or what remains of it) as that nor mally responsible for the act of standing. The same muscles are brought into play and the force of contraction in the different muscles depends in the same way on sensory messages from the labyrinths and from the muscles themselves. Thus a change in the position of the head relative to the ground alters the distribution of the rigidity owing to the stimulation of the labyrinths, and the amount of contraction in each muscle is governed by the sensory impulses arising from it, so that the pull is just adequate to the load.

There is one group of sensory impulses from muscles which has a special influence on the distribution of the rigidity and plays an important part in the normal posture. These are the impulses arising from sense organs in the muscles of the neck. If the head is bent out of its normal position relative to the trunk one or other set of neck muscles will be stretched, the sense organs in the muscle will be stimulated and so any deviation from the nor mal relation of head and body will be signalled at once to the brain. The effect of these impulses can be seen most clearly after the destruction of the labyrinths, since these also will be stimu lated by head movements. When the labyrinths are destroyed it is found that bending the head into any position will modify the posture of the body and limbs, usually in such a way as to bring the trunk into line with the head. For instance, if the head is bent upwards the rigidity increases in the fore limbs and dimin ishes in the hind limbs, so that the animal squats on its haunches with the body inclined upwards in line with the head; if the head is rotated, the extension of the limbs increases on the side towards which the jaw is turned, so that the body tends to rotate on its long axis in the same direction as the head.

The discovery of these reactions arising from the neck muscles in decerebrate rigidity provided the clue to the analysis of the postural reactions in animals with the brain stem intact. We have seen that an animal suspended in mid air brings its head into the normal position owing to impulses from the labyrinths reinforced in some cases by the eyes. This initial righting of the head will bend the neck and start a fresh set of sensory impulses from the neck muscles, and these will produce the movements needed to bring the body into line with the head. Thus the position of the head in relation to the earth is determined by the labyrinths and the position of the body is determined by that of the head.

In an animal with the brain stem intact, these two sets of re flexes enable the animal to regain its normal posture ; they do not merely indicate how it might be regained, as they do in decerebrate rigidity. A third set of reflexes also appears when the brain stem is intact, reflexes arising from unequal stimulation of the body wall and enabling the animal to bring its body into the normal position even though the head is prevented from righting itself. These are not equally developed in all animals; it is well known, for instance, that the best way to keep a horse lying on its side is to sit on its head. Here the body is not righted independently, though righting movements follow once the head is released.

By the co-operation of these reflexes an animal with intact brain stem can bring its body into the normal standing posture. To maintain its equilibrium during movement a further series of reflexes comes into play depending partly on impulses from the eyes and labyrinths and partly on impulses from the muscles. Many of these have been worked out in detail and, as before, the nervous control is carried out by the brain stem.

There is, however, a vast difference between the behaviour of an intact animal and one deprived of its cerebrum. The latter can stand, walk and run and it may even show some spontaneous activity, but it has none of the variety of movement of a normal animal. When the cerebrum is absent, the maintenance of equili brium is the dominating activity; when it is intact an animal like a dog or a cat can lie on its side and turn its head in all directions without turning its body. The postural reactions are no longer dominant though the animal is still dependent on them for its normal equilibrium. The greater the development of the cerebral hemispheres the less easy does it become to trace the sequence of reactions involved in balancing the body, and in man, though it is possible to detect the postural reflexes from the labyrinths, eyes and neck muscles, there is none of the mechanical obedience to them which we find in a guinea pig or a rabbit. For the adjust ments necessary when movement is so largely controlled by the cerebrum, the brain stem mechanism is probably reinforced by the cerebellum which is closely linked with it and with the cere brum.

The exact function of the cerebellum is still to some extent a puzzle, for its removal in a normal animal causes gross inco ordination and no other symptoms, yet in an animal with the cerebrum destroyed the presence or absence of the cerebellum makes no difference. The explanation appears to be that in the higher mammals the cerebellum has become a subordinate part of the cerebral apparatus and so has little function when the cere bral control is removed. Until we know more of the cerebellar mechanism, the finer details of muscular adjustment will remain uncertain, and this applies particularly to the balancing reactions which are acquired after infancy; e.g., those involved in riding a bicycle. But the basic reactions of equilibrium are those of the brain stem and their analysis has already shown what may be achieved by the co-operation of a few fairly simple reflexes.

For equilibrium of forces, etc., see MECHANICS; for chemical equilibrium see CHEMICAL ACTION; for other forms of physical equilibria see RADIATION, THEORY OF; THERMODYNAMICS; RADIO ACTIVITY. (E. D. A.)