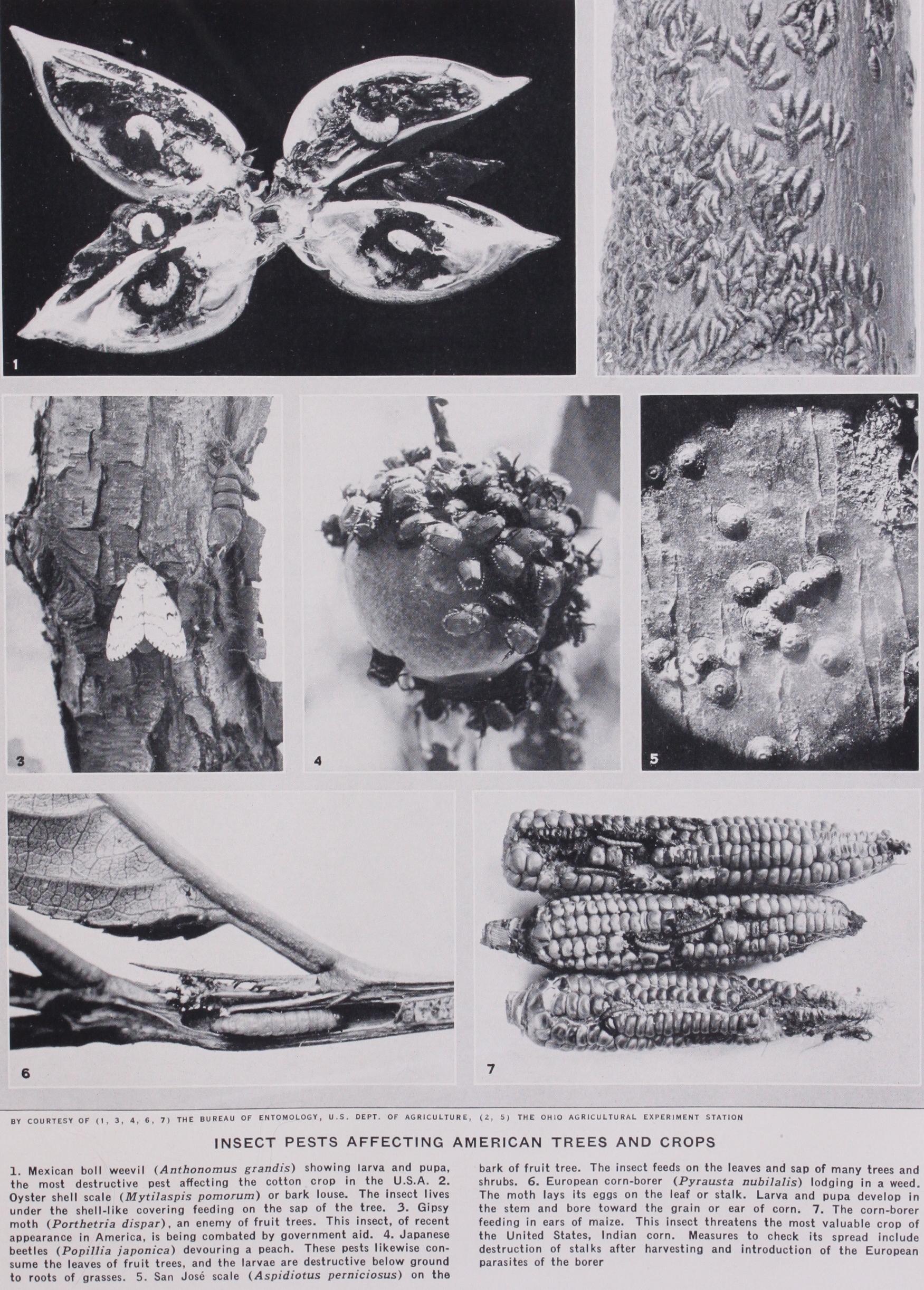

Beneficial Insects

BENEFICIAL INSECTS It is only too often overlooked that man derives vast direct and indirect benefits from insects. Practically every species is preyed upon and kept within hounds by the attacks of other insects, either parasites or predators, while bacterial and protozoal diseases, birds and insectivorous mammals, also contribute to the destruction of a large bulk of insect life. But for these natural controls man would stand little chance of successfully competing with insects in maintaining his food supply. Among predators, ground beetles and ladybirds along with their larvae, together with larvae of lace wings and many flies, are of great importance, but the palm of ef ficiency must be allotted to the parasitic forms such as Tachinid flies, and almost all members of the great groups of parasitic Hymenoptera, which probably account for the destruction of a greater proportion of insect life than we have adequate means of appreciating. The importance of these predators and parasites is becoming increasingly recognized by economic entomologists, and is further discussed in the succeeding section on control measures.

There is also to be recollected the fact that insects are the most important of all agents concerned with the pollination of flowers. In the case of fig-growing the flowers of the cultivated fig need to be pollinated from the wild or caprifig. The structure of the fig flower is such that pollination requires to be carried out by the intervention of a small Chalcid Blastophaga. In California and elsewhere profitable fig-growing did not become possible till this insect was introduced and established so that it could carry out its useful work. One need scarcely mention the enormous bene fits man has derived from the use of honey, beeswax and silk. Lac, which is still an important commercial product, and has not been supplanted by any artificial substitute, is yielded by the Indian scale insect (Tachardia lacca). Cochineal is yielded by another Coccid, Dactylopius coccus, indigenous to Mexico, but now established in other lands, and the drug cantharidin is obtained from blister beetles (family Cantharidae). Again, sev eral kinds of insect are used as ornaments, such as the ground pearls of the West Indies and the Buprestid beetles of the Orient and South America, while many showy butterflies and beetles are used for various decorative purposes. Finally, a number of insects are, or have been, used by uncivilized man as food. Apart from manna of biblical times—which is almost certainly a kind of honey dew—grasshoppers, caterpillars, water-boatmen and termites are used as food by various races. Many aquatic insects are important items in the diet of fresh-water fishes, and other insects are used by anglers as bait.

Another possible benefit to be derived from insects is their utilization in checking the spread of noxious weeds resisting all other measures of restraint. Success in this field has been achieved in the Hawaiian Islands, in checking the spread of Lantana by in troducing into that territory insects which prey upon that plant in its natural home in Mexico. Strenuous and encouraging efforts are being made to control prickly pear in Australia by similar means, and experiments are being carried out with a view to attempting the control of blackberry, gorse and other noxious weeds in New Zealand by insects imported from other parts of the world. Work of this character has its drawbacks and every care has to be ex ercised lest the introduced species may turn their attention to economic plants and so become pests rather than benefits to the countries concerned.

Methods of controlling noxious insects are very diverse and are discussed under four headings below.

Cultural Methods.

Cultural methods as a rule involve some change in the normal course of agricultural operations and fre quently they have the advantage of being preventive rather than remedial in effect. Such methods aim at enabling the crop to escape the severity of attack by a specific pest by altering the time of sowing, by special type of cultivation or manuring, by chang ing the rotation so that the susceptible crop occupies a different place in the rotation scheme, or by the use of a less susceptible variety of the crop concerned. It is also to be remembered that many pests are concealed feeders and are, therefore, safe from the effects of insecticidal treatment, or the crop may be of such a character as to render such treatment impossible. As examples of cultural measures the following are noteworthy. The only satis factory means of coping with the frit fly consists in sowing suffi ciently early, so that by the time the insect appears the crop has reached a stage when it is not liable to attack. Attacks of wheat bulb fly (Hylemyia coarctata) may be avoided by never allowing that crop to follow a summer fallow or early potatoes, since the eggs are laid in the bare soil or on ground sparsely covered by a growing crop. Again, American vines are largely resistant to the gallicolae generations of the Phylloxera, certain varieties of cotton are resistant to attacks by leaf-hoppers, and apples grown on North Spy stocks are not liable to attack by woolly aphis. Manuring with nitrogenous fertilizers has been shown to facilitate the recovery of tea from attacks of the shot-hole beetle borer in Ceylon, and phosphatic manures appear to hasten the maturing of the ears of barley to a condition which is less liable to attack by gout fly. In Trinidad the control of the sugar-cane frog-hopper is no longer an entomological problem, but is one of cultivation. Under conditions where the water content of the soil is disturbed, it is probable that the constitution of the sap of the plants is altered and that water shortage is a possible cause of increased susceptibility to frog-hopper damage.

Physicochemical Methods.

Most measures which come un der this category are remedial rather than preventive and the most important involve the application of chemical substances termed insecticides. Insecticides may be divided into stomach poisons, contact poisons, fumigants and winter washes. Many of them may be applied either in the form of wet sprays or as dusts.Stomach poisons are effective against biting insects which devour foliage, and their object is to coat the plants with a toxic sub stance which the insects will devour, along with their food. In the application of sprays the essential basis, therefore, is the toxic compound, but other material (soap, etc.) has to be added in order to facilitate the mixing of such a compound with water and to ensure its spreading over and effectively wetting the foliage. Among the best-known stomach poisons are arsenicals, especially Paris green, lead arsenate and calcium arsenate.

Contact poisons are used against sucking insects which derive their nutriment from the sap. It is evident that coating the plant with an external poison will have little effect against pests of this character and consequently contact insecticides, which kill by being applied to the outsides of the insects themselves, become ne cessary. The most valuable of all contact insecticides is nicotine, which is largely used in the form of nicotine sulphate at the rate of one gallon of the compound (containing 4o% nicotine) to about Boo to i,000gal. of water. Among other contact insecticides pyre thrum, derris, quassia, oil-emulsions, soaps and lime-sulphur are used for various pests.

Fumigants are effective in glasshouses, warehouses and also for treating living trees in the field, in which case the plants are cov ered with special hoods or tents for the purpose. Hydrocyanic acid gas is one of the best-known fumigants for glasshouse work throughout the world ; carbon di sulphide is put to various uses and is also applied against root pests in the soil. Among other fumigants, nicotine, carbon tetra chloride, chlorpicrin and paradi chlor-benzene may be mentioned.

Winter washes are applied dur ing the dormant season and are designed to kill the eggs and other over-wintering stages of in sects present upon the trunks and branches of .fruit trees. Such washes include caustic alkalis, lime-sulphur, miscible oils and tar distillate compounds.

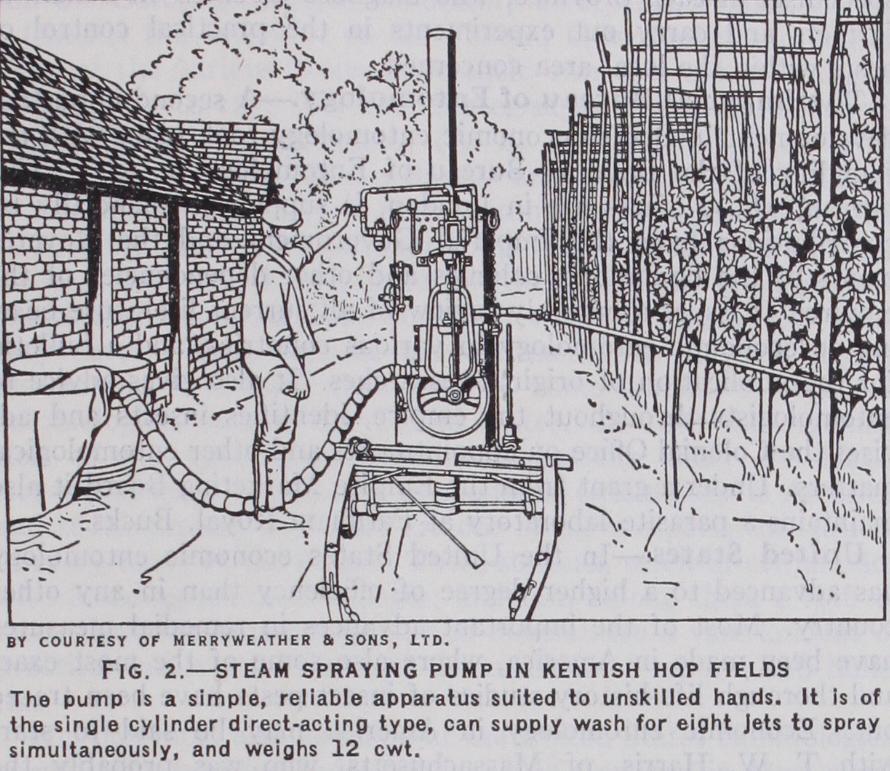

The usual method of applying insecticides is in the form of sprays, and on a small scale, knapsack sprayers (fig. r) which can be carried on the back of the operator, are widely in vogue. On a field scale horse-drawn or mechanically driven machines are necessary (fig. 2) and many patterns are on the market. The nozzles aim at producing the spray in a fine mist and can be fitted to any length of tubing so as to reach to the tops of high trees if necessary. Pumps keep the insecticide constantly mixed, and at the same time discharge it forcibly through the nozzles wherever it is required. In America the use of insecticides in the form of dusts has come greatly into use during recent years. The toxic compound is used in powdered form, diluted and mixed with a suitable carrier such as kaolin, hydrated lime or ground dolomite.

The dusting can either be done by hand machines or horse drawn apparatus. In the latter case the dust is expelled by the air blast created by a fan which is geared to the wheels of the machine. At the present time dusting materials are usually more expensive than those required for spraying, but the labour and time consumed are less and the equipment lighter and more easily used on bad ground. Also, the water difficulty-40o to 5oogal. being required to spray an acre of fruit trees—is done away with. Dusting, how ever, can usually only be carried out when the foliage is wet with dew to give adhesion to the particles and is precluded by high winds. During the last seven years the use of the aeroplane has come very much to the front in the United States, particularly for dusting cotton with calcium arsenate against the boll weevil.. Many acres of fruit have also been treated by this method, and by applying Paris green, large areas of standing water have been dusted to kill mosquito larvae. The evolution of types of aero planes capable of manoeuvring under the special conditions re quired, has led to rapid advances in this method of control. Be fore many years elapse it is likely to be widely used in the control of forest pests and locust invasions, and tests have already been carried out in Germany, Russia and other countries. In Great Britain the uses of the aeroplane are very limited, but in the cases of potatoes and fruit where considerable areas are under cultiva tion, the method has its possibilities. Among the advantages of the aeroplane is speed, it being possible to dust 600 to I,000ac. in one hour and one plane is capable of doing the work of so to 75 cart dusting machines in the same time.

Among other physicochemical methods the use of heat for killing pests in mills and warehouses is coming to the fore, while in some cases light traps are effective in the quantitative destruc tion of such pests as the paddy borer. As a rule, however, the expense and trouble of maintaining light traps are not commen surate with the results obtained. The use of attractive volatile re agents has great possibilities as lures, very much on the same prin ciple of the moth collector's sugar mixture. Fermented molasses is used as a bait for the destruction of vine moths in France and geraniol has recently been shown to be powerfully attractive to the Japanese beetle in the United States.

Biological Methods.

Biological or natural methods of con trol involve the use of parasites, predators, or disease organisms for the purpose of ensuring a high rate of mortality to the par ticular pest concerned. This type of control has been successful in cases where a noxious insect has been introduced into a country unaccompanied by those natural enemies which restrain it in the land whence it came. The first example of this kind was achieved in 1889, when the Australian ladybird (Novius cardinalis) was intro duced into California for the purpose of destroying the cushiony scale (Icerya purchasi) of citrus fruits. The experiment proved so successful that this method of control has been applied in almost all countries where that pest has been prevalent, with equally satis factory results. In the Hawaiian Islands almost all the pests of sugar cane have been so effectually controlled by biological means that they are no longer a menace. Special mention needs to be made of the control of the cane leaf-hopper by Chalcid wasps and a Capsid bug (Cyrtorhinus mundulus) introduced from Queens land and Fiji. The cane-borer beetle has also been largely kept under control by a Tachinid fly obtained in New Guinea, and the Anomala beetle by a Scoliid wasp from the' Philippines. Great benefit has been derived from the introduction of a tiny Chalcid (Aphelinus mali) from the United States into New Zealand, where it is effectually destroying the woolly aphis of apple. In Fiji the coconut moth gives every promise of being controlled by a Tachinid fly which is prevalent in Malaysia. There are again other cases where results have not been so readily obtained, and efforts have been going on for many years to secure some measure of control over the gypsy and brown-tail moths by the importation of a whole range of parasites that attack these insects in their various stages. In the same way likely parts of the world are being searched for parasites of the European corn-borer, the Japanese beetle and other introduced pests of the United States.