Danzig Vilna Memel Fiume Corfu Saar Ruhr

DANZIG; VILNA; MEMEL; FIUME; CORFU; SAAR; RUHR; and RHINELAND). It is only necessary here to emphasize the charac teristics of the new Europe that emerged from the war and to indicate the general course of relations between the different European States. Not only was the World War the greatest known to history by reason of its extent, the size of the armies engaged, the number of casualties and the greatness of the dev astation and cost ; it resulted in a political, social and territorial revolution which exceeded in violence and results all previous revolutions. Europe emerged transformed.

The Transformation of Europe.

Nearly all the European States had been involved sooner or later in the war ; only Spain, Switzerland, Holland, Denmark, Norway and Sweden had re mained neutral. The Napoleonic wars resulted in a general re-distribution of Europe; so, too, the World War resulted in yet another distribution—but in a very unequal manner. The national States formed on the exterior parts of Europe preserved their territories—some intact (Sweden, Norway, Luxembourg, Holland, Switzerland, Great Britain, Portugal and Spain) ; others, one exception, increased their territory in accordance with the principle of nationality. Thus France recovered Alsace and that part of Lorraine which she had lost in 1871, Belgium re ceived back the cantons which had been taken from her irr 1815, and Denmark obtained the Danish portion of Schleswig. Serbia and Rumania received large accessions of territory through annexation of districts inhabited by Serbian and Slovene or Rumanian-speaking peoples, while Italy not only received Italian speaking districts of the Trentino, Trieste and Zara, but all the southern portion of the German-speaking Tirol and the Slovenian districts on the Adriatic.The three military empires, which covered the great central mass of Europe, were reduced or dismembered by the separation of all the districts inhabited by peoples of a foreign nationality. The German empire lost, apart from the districts restored to France, Belgium and Denmark, all its eastern Polish-speaking districts, Posen, West Prussia, the district of the Kashubes, and that part of Upper Silesia which voted in the plebiscite taken in 1921 for annexation to Poland. For economic reasons, Danzig and the Saar mines were the subject of special treatment.

The Russian empire lost all the territories on its western frontier peopled by foreign nationalities :—Finland, which was already autonomous, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Russian Poland were erected into sovereign States. Some parts of White Russia and of Ukrainian Volhynia were annexed to Poland, while Bessarabia went to Rumania.

The Austro-Hungarian empire disappeared, and the two f or mer dominating peoples kept only that territory in which their nationals formed the majority of the population. They formed two little national States—German-Austria and Hungary; of the rest of the empire part was divided among three neighbouring States, Italy, Serbia and Rumania, and the rest helped to build the revived Poland and the new State of Czechoslovakia.

The dismemberment of the Austro-Hungarian empire altered the dimensions of the two Balkan States, whose territory has been extended far beyond the Balkan peninsula ; Rumania united within her frontier all Rumanian-speaking peoples; Serbia has become the kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, or Yugo slavia. The rest bf the Balkan peninsula was divided between Greece, a diminished Bulgaria and Albania.

This rearrangement of the map of Europe increased the number of sovereign States and upset the balance of power. In 1914, excluding the Ottoman empire, there were six great Powers. There are now only five; as against one State of moderate size (Spain), there are now five—Spain, Poland, Rumania, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia; as against I1 small States there are now 16, including five new States, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Albania and two created out of the debris of the empire, German Austria and Hungary; as against two very small States there now remains but one, Luxembourg. Thus the total has been raised from 20 to 27. Europe has never before had so many States of medium size. It has been impossible to exclude them from the European concert, in which they have filled the gap between the Great Powers and the little States.

The Political Revolution.—Only in one part of Europe did the war bring about a political revolution. All the national States other than the Central Powers retained their representative and democratic Constitutions; only three were republics (France, Switzerland and Portugal) ; Spain became a republic in 1931; Greece in 1924, but restored the monarchy in 1935. The Habs burgs, Romanoffs and Hohenzollerns have disappeared and their States have, for the most part, adopted in name, or in practice, some form of dictatorial government. Germany's attempt to establish a republican form of government collapsed in Hungary remains nominally a monarchy, although she is still without a king. Albania became a kingdom in 1928.

Russia was organized by the Communist party into a federa tion of republics, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.). The proletariat, which is the legal sovereign, is represented by a congress elected on a franchise restricted to proletarians of both sexes. The Communist party wields the dictatorship in the name of the proletariat under the form of an absolute and centralized round. This form of government did not originate in Russia, but in the principles of Marxism, and may be regarded as being not only the national organization of a State, but also an instrument by which to consummate the proletarian revolution throughout the world.

These revolutions have upset the ratio between the types of political regimes. Before the war Europe contained only three republics as compared with 17 monarchical States, and including five great Powers, one medium Power, nine minor States and two very small States. Since Greece has become a republic there remain only 13 monarchies, including the two great Powers, Great Britain and Italy, Hungary, a monarchy without a king and Albania a kingdom since 1928. There are now 13 republics, in cluding three Great Powers, France, Germany and Russia. Thus the greater part of Europe has become republican.

The Financial Revolution.—The war involved the belliger ent States in unheard of expenses, of which only a very small part was covered by taxation. The Governments were forced to have recourse to loans of different kinds, and with the exception of Great Britain, the issue of paper money in such quantities that the real value of the legal currency became depreciated in an unprecedented manner. The national expenses were increased by the interest on these loans to a degree which made it impos sible to balance the budgets, and upset the value of money, which is the standard for all values. This policy was pursued by nearly all the States, even after the peace and resulted in a chronic deficiency in budgets, the fall of State stock, the depreciation of currency and in three States, Russia, Germany and Poland, ended in complete bankruptcy. England alone has been able to restore her currency to par. Economic life became completely revolutionized by high salaries and high cost of living, sudden fluctuations of exchange, and—in England—by unemployment on a scale never before reached.

The financial and economic crisis became the dominant inter est of politicians throughout Europe, and it has been the task of Governments to find expedients to enable them to meet their loan liabilities and balance their budgets. This preoccupation so strengthened the national sentiments that all the Continental States were moved to raise their customs duties to an unprec edented height. It also brought about an augmentation in the wages and pensions of the labouring and commercial classes, weakened the resources of the privileged classes, equalized the standard of life, raised the condition of women, and in brief, Americanized Europe.

The Destruction of the Concert of Europe.

The change in international relations was reflected in the negotiations that resulted in the Treaty of Versailles. Of the six great Powers forming the European concert, three were absent; Austria was destroyed; Bolshevik Russia had become isolated; Germany was the object of the negotiations without being called upon to take part in them. The treaty that has been nicknamed by the Germans "the dictation of Versailles," disarmed Germany, com pelled her to submit to a military occupation and deprived her of any active part in European politics. The settlement of Europe was thus regulated by three European Powers, Great Britain, France and Italy, together with Japan and the United States. Wilson had announced that the procedure would follow another method than that employed by the Congress of Vienna in which decisions had been arrived at in secret by "potentates" without any regard for the feelings of the people. He endeavoured to work in public and to put into action the principle of the right of peoples to determine their own fate. But in reality the delibera tions were secret, the work was done by commissions whose personnel had been chosen by the Governments, and the final decision was made by a council composed of the Governmental chiefs of the five great Powers. Having little interest in European affairs, Japan left these matters to the four other Powers, who became known as the Big Four, and since the Italians were re duced to play a secondary role, the decisions were taken by three great Powers, Great Britain, the United States and France, which meant in effect, by Lloyd George, Wilson and Clemenceau. When the Allies had reached an agreement on the conditions of peace, their agreement assumed the force of a contract which could not be discussed without dissolving their unity, and they imposed it upon the vanquished in five distinct treaties. When Wilson refused to agree to the reserves which the American Senate added to the treaties, the United States withdrew from the con cert and the three European Powers, Great Britain, France and Italy, alone remained. This rump of the concert of Europe under took the application of the treaties and the chiefs of the Governments continued to compose a Supreme Council (q.v.) which settled the affairs of Europe in conferences between min isters that were held at Spa, in July 1920, in London in Feb. 1921, and at Genoa in April 1922.Matters of secondary importance were left to the Conference of Ambassadors (q.v.), created in 1920, and meeting in Paris, whose functions were limited to the execution and interpretation of treaties, received the reports of the commissions charged with the delimitation of frontiers, and settled the territorial arrange ments resulting from the plebiscites ordained by the treaties. Its members were each responsible to their own Governments and it operated as a clearing house for avoiding the delays in curred in ordinary diplomatic procedure.

The New Organ of International Law.—By accepting the Covenant, which created the League of Nations, the signatories of the Treaty of Versailles introduced into international relations a principle and a new system. From the earliest times the con duct of Governments had been regulated solely by an indefinite tradition, which, even when embellished by the name of inter national law, consisted solely in variable customs without any obligatory force. Interests of State as interpreted by the sover eign, were the sole rule of policy, and the Governments con ducted their relations with other States according to the prin ciples of Macchiavelli, which were revived from Bismarck's time under the name of Realpolitik. The European congresses amounted to no more than temporary organizations set up to settle transient matters and were composed solely of representa tives of the States whose interests were directly involved.

The war inspired in the European peoples a passionate desire to prevent its recurrence by imposing on their Governments as a duty the maintenance of peace. The League of Nations is an institution radically different from a congress of the European concert. It is a permanent body with a staff of permanent em ployees holding periodical meetings and always prepared to act without delay in regulating differences between States before they have had time to develop into dangerous conflicts. Its power is not limited to any region or to any question, and extends over the whole sphere of relations between all the States-members. Neither does it work after the fashion of the congresses, in the tense atmosphere of the capital of a great Power, but at Geneva in the calm surroundings of a neutral town. It is its express mis sion not to serve particular interests, but to maintain peace by demanding from all States respect for treaties and international law. For the first time the Governments have recognized a moral obligation to submit their activities to the rule of universal justice.

From the former concert of Europe the great Powers have preserved for themselves the privilege to a permanent seat in the executive Council, but they are in a minority as compared with the representatives of States elected by the Assembly, while in the Assembly itself all States are on an equal footing. The dis cussions of the Assembly and the Council are held in public, and although secret intrigues outside the meetings may not be without influence, the publicity, and the meeting together in Geneva, of statesmen from the whole world has given to the small nations an influence which they could never have attained in the days of the concert of Europe. They use this influence for the maintenance of peace by the creation of an international public opinion which makes itself felt in the Governments of the great Powers. The settlement of difficulties is facilitated by means of the Court of International Justice set up at The Hague in 1920-21.

The League was endowed by the treaties with permanent powers in regard to the colonial mandates, National Minorities, Danzig, the Saar Basin, in virtue of which it has already taken numerous decisions. The great Powers have in addition, by common agree ment, entrusted it with the settlement of the Upper Silesian question, which proved beyond the capacity of the Conference of Ambassadors. Its decision, which was put into operation with out delay, established a precedent for an extension of its author ity. It also regulated with success the differences between Sweden and Finland over the Aland Islands in 1921, the frontier differences between Albania and Yugoslavia, and frontier inci dents arising between Bulgaria and Greece.

Conflict with Communist Russia.

War was prolonged in Russia by the campaign carried on by the White generals, sup ported by the Allies, against the Red armies, while the Moscow Government sought to promote Communist revolutions in the European States. This crisis was of short duration and only a single country, Hungary, was governed for a few weeks by Communists. After they had driven the Polish troops from the Ukraine, the Red armies arrived within sight of Warsaw before they were thrown back in disorder in 1920. The Soviet Govern ment concluded peace treaties at Riga with the Baltic States.The Communists repudiated the Russian debts, annulled con cessions to foreigners, and confiscated their deposits in the banks. At first the European Governments refused to recognize the Soviet. But industrial and commercial interests wished to resume relations with Russia in order to open up her stores of petrol, wheat and minerals. The Bolsheviks appealed for foreign cap ital to reorganize their industry. The rapprochement began with the Treaty of Rapallo, which they signed with Germany in 1922, during the Genoa Conference. The Soviet Government was subsequently accorded official recognition by the ministries of Ramsay Macdonald in Great Britain and Herriot in France in 1924 ; and the other States followed suit. Subsequently Russia kept a diplomatic representative in all the capitals, and made use of them to stir up revolution. The Conservative cabinet in Eng land adopted measures, in 1927, to counteract this propaganda and in May of that year raided the offices of the Soviet Com mercial Delegation and broke off diplomatic relations. The Soviet maintained a hostile attitude towards the League of Nations and refused in 1926 to ask to be admitted to membership.

The Successor States and the Little Entente. The

de struction of the Habsburg monarchy, which was an event with out precedent in the history of modern Europe, was the work, not of its enemies but of its subjects. The national States, new or transformed, which took the place of the empire, had to reorganize a whole system of institutions, and to build up a political and administrative personnel in countries devastated by four years of war and plunged without preparation into a system radically democratic. The treaties compelled them to grant com plete equality of political rights to national minorities of differ ent language and religion; the right of teaching their language in schools and using it in the Church services and law courts was placed under international guarantee and control of the League of Nations (see MINORITIES).The dismemberment of the Austrian empire substituted several States, each with its own independent Government, for one vast united territory ; it resulted in internecine conflicts such as were usual in the Balkans; hence the catchword "the balkanization of Europe." But the Governments of the Successor States (q.v.) felt themselves to be threatened by the same adversaries, and therefore banded themselves together into what is known as the Little Entente (q.v.) without consulting the great Powers. Benes, the foreign secretary of Czechoslovakia, took the initiative ; he concluded a treaty of defensive alliance with Yugoslavia in Aug. 1920, and a similar treaty with Rumania, April 1921, who there upon concluded a treaty with Yugoslavia, June 1921. The three States, to all of which a part of Hungary had been annexed, thus protected themselves against the protests of the Hungarians. They intervened, Oct. 1921, in order to prevent the restoration of Charles as king.

Rumania, in order to defend herself against Russia, concluded a treaty with Poland, 1921 ; Czechoslovakia concluded a treaty of guarantee with Austria, Dec. 1921, the first of the kind between one of the victorious and one of the vanquished States. The system of guarantee was completed, 1924, by the Treaty of Rome concluding an alliance between Italy and Yugoslavia and the treaty of alliance between Czechoslovakia, Italy and France. All these treaties were registered by the League of Nations, The destruction of the economic unity of the Austro-Hungarian empire raised a further problem. Vienna had been the financial centre of the banks, distributing capital and directing commerce in all the territories. Now each of the Successor States regulated as sovereign its financial policy, each wished to create its own industries and to protect them by high tariffs. Commercial ties between the countries were rudely broken; communications were upset by the division of the lines and rolling stock of the rail ways. Two remedies were suggested ; a customs union between the Successor States, and the union of Austria and Germany; they were refused both by the States and by the Great Powers.

Conflicts on the Adriatic.

Italy had not obtained exclusive domination of the Adriatic. The treaty had given Dalmatia to Yugoslavia and made Fiume autonomous. A sudden attack put Italy in possession of Fiume. The Fascist Government of Mus solini after 1922 gave an aggressive air to the policy of Italy by demonstrations devised to appease national amour propre, but this was balanced by a prudent diplomatic practice. After the murder of Italian officers belonging to the commission for the delimitation of the Greco-Albanian frontier, he sent a fleet to occupy Corfu; but he accepted the verdict of the Conference of Ambassadors. He concluded with Yugoslavia the treaty regulating the question of Fiume, 1924, by a division of territory. He showed consider able diplomatic activity in eastern Europe by concluding treaties with Hungary, Greece and Rumania, which were interpreted as an attempt to isolate Yugoslavia. He worked for the imposition of Italian influence in Albania by the Treaty of Tirana (1926). The Serbs protested ; the quarrel seemed to be made up after negotiations between Italy, France and Yugoslavia, which resulted (1927), in a treaty between France and Yugoslavia.

Polish Disputes.

The treaties had given Poland a large tract of territory without fixing its definite boundaries, which did not become settled until after a series of violent quarrels with her neighbours. The Poles made war on the Ukrainians (1919) in order to subject Lemberg and Galicia, and imposed on these Ruthenian-speaking countries—instead of the autonomy intended by the treaties—a system of occupation which was tolerated by Europe. The invasion of the Ukraine, pushed as far as Kiev, was stopped by the Russian Red army (192o). On the side of Lithuania, after the sudden attack on Vilna (q.v.) (192o), the frontier was drawn by the Conference of Ambassadors, who ac cepted the fait accompli; but Lithuania refused to recognize it. The attempt to form an alliance of the Baltic States against Russian communism made at the Conference of Warsaw (1921), failed on account of a disagreement with Finland. The Russian frontier, fixed by the Treaty of Riga, left Poland in possession of the occupied territory. On the side of Germany the settlement of the frontier necessitated the intervention of the League of Nations over the question of Upper Silesia, where the plebiscite resulted in an open war between the Poles and the Germans.

Relations with Germany.

The chief preoccupation of European diplomacy has been the relations between the Allies and Germany, on which depended the agreement between Great Britain and France. The French formula, "restitution, reparation, guarantee," required a complicated system. The French general staff claimed as a guarantee the indefinite military occupation of the left bank of the Rhine; Clemenceau accepted an occupation limited to 15 years in exchange for an American and British guarantee. But the refusal of the United States to ratify the treaty, annulled this promise; the French Government have therefore been occupied ever since in finding an effective guaran tee. French nationalists, who have become influential since the success of the Bloc National in the elections of 1919, hoped to make themselves secure by reducing Germany to a state of partition ; they hoped to detach from Berlin the Catholic Rhine land. The British Government saw no lasting security except in a reconciliation with Germany, and f ought against all schemes for destroying German unity.The Allied Governments did not desire to fix the sum due from Germany for reparations, for fear of creating too much disap pointment in France. They called three conferences, at Spa (192o), London (1921), Genoa (1922), for the purpose of set tling with Germany the best means of obtaining her payments and the share each ally was to receive. The French Government tried to work upon Germany by exerting military pressure; they took the opportunity of the dispatch of German troops against the communists in the neutralized zone to extend their military occupation as far as Frankfurt (192o), and then into the Ruhr. The president of the republic, Millerand, intervened to put a stop to the negotiations at Genoa. The accord between Great Britain and France was therefore broken; and Lloyd George, after his resignation, conducted an open campaign against French policy. The Bonar Law ministry tried to re-establish friendly relations at the conference of Paris, Jan. 1923, by a plan which diminished the French debt to England. The Poincare ministry rejected it and carried out a previously thought-out plan to work German industries under the direction of French engineers, and occupied the industrial region of the Ruhr (q.v.). The passive resistance of the Germans ruined German currency and stopped the payment of reparations. At the same time armed bands made "separatist" demonstrations on the left bank of the Rhine with the connivance of the French army of occupation.

The crisis was resolved in 1924 by the adoption of the Dawes Plan (q.v.) . The victory of the party of the Left at the elec tions, who represented the peace-loving mass of the French electorate, led to the formation of a ministry which pursued a more pacific policy in foreign affairs and re-established good relations with Great Britain.

The Guarantee Treaties.

The French Radical ministry and the British Labour Government agreed to revive through the League of Nations the scheme for general disarmament promised by the Treaty of Versailles. The French Government saw in this a means to obtain the abortive guarantee of 1919 by making it a preliminary condition of disarmament. Its formula was "secu rity, disarmament, arbitration." The Geneva protocol of 1924 was drawn up in this spirit ; the members of the League of Nations were to undertake to support each other against all aggression and to enforce sanctions against the aggressor. But the British Government, representing the whole of the British empire, had to reckon with the repugnance of English opinion to any general commitment, and still more the refusal of the dominions, members of the League, to promise to intervene in purely European conflicts. The protocol therefore was wrecked.The scheme extended to all the members of the League seemed to be too great; Briand said "In order to ensure peace it is Europe which must be organized." The policy of guarantee was raised again in the form of special treaties, to which the British Government took no exception. The project proposed confi dentially by the German to the British Government, March 1925, was accepted by France and discussed at Locarno (q.v.) in October. The agreement was signed in London in the form of treaties between Germany, on the one hand, and Great Britain, France and Belgium oil the other. The contracting parties en gaged themselves to abstain from all aggression, to respect the frontiers established in 1919 and to submit all differences between them to arbitration. Great Britain and Italy engaged themselves to guarantee the treaties by going to the help of any State attacked. This agreement meant that Germany renounced Alsace Lorraine, but by accepting an arrangement which had in the first instance been imposed upon her by force, she treated with the other Powers on an equal footing. She was to ask for admission into the League of Nations and to receive a permanent seat on the Council.

France wished for an analogous agreement for the eastern frontier between Germany and Poland ; this was known as the "Eastern Locarno." But the Germans refused to accept as final either the regime imposed on Danzig, or the Danzig cor ridor, or the division of Silesia, and the British Government did not wish to undertake to intervene in 'eastern Europe. Germany merely gave up her claim to go to war to alter the frontiers. She concluded treaties with Poland and Czechoslovakia which sub mitted all their differences to arbitration; France, by a separate instrument, promised to guarantee them.

The admission of Germany to the League of Nations, proposed at a special meeting at Geneva in March 1926, was delayed by the opposition of Spain and Brazil, who wished to take advantage of the occasion to gain for themselves a permanent seat. The admission of Germany was decided at the session of Sept. 1926. The German foreign minister, Stresemann, took his seat on the Council, where he used his influence in 1927 in the direction of peace and disarmament. Germany had re-entered the Concert of Europe, as France had done in 1818 ; but she remained under special obligations by the occupation of her territory and the limitation of her military, naval and air forces.

The success obtained by the system of guarantees in the direction of security diminished resistance to schemes for dis armament. Negotiations began again for the "general limitation of the armaments of all nations" promised to Germany at the Treaty of Versailles, and recognized as necessary by Article VIII. of the Covenant of the League. A preliminary meeting at Geneva, Nov. 1927, in which a Russian Soviet delegation took part, set up a commission to report on the conditions for a reduction of armaments.

The autumn session of the League of Nations, 1927, was held in a calm atmosphere. The representatives of Poland and Lithuania, countries in a condition of permanent conflict, de clared at Geneva, in Dec. 1927, that their countries were not in a state of war, although Lithuania continued to claim Vilna. The year 1928 opened without grave disagreement in any part of Europe. The Little Entente limited itself to protesting at Geneva against the illegal importation of machine guns into Hungary. Russian revolutionary propaganda was diminished by disunion among the communists.

But the conflict between Poland and Lithuania, continued in spite of the intervention of the League of Nations and was only settled by the Konigsberg conferences. In the South Ahmed Zogou, considered as the agent of Italian politics, was proclaimed king of Albania (August) which prejudiced the re-establishment of friendly relations between Italy and Yugoslavia. On the other hand the international atmosphere was lightened by the combined effort of the great Powers in favour of peace. The Kellogg Pact by which the contracting parties were pledged to renounce war as a political instrument, was signed on Aug. 27, in Paris by the United States and the majority of the European Powers. The 9th Assembly of the League of Nations in Geneva discussed in a pacific spirit the evacuation of the Rhinelands and the Polish Lithuanian conflict, and the president of the Preparatory Corn mission for the Limitation of Armaments was invited by the Council of the League to be ready to convoke the commission "in any case" at the beginning of 1929. The favourable impression was, however, a little decreased by the criticisms made by the United States on Sept. 29 on a Franco-British agreement referring to the limitation of war navies, and which American opinion con sidered directed against the United States.

On Feb. I1, 1929, a treaty was signed, between the Vatican and the Italian State, which put an end to the discord of nearly 6o years, and restored to the papacy its status as a sovereign power over a small area of Rome—"The city of the Vatican." See further especially the article PAPACY and also ITALY, PIus XI., VATICAN, etc.

Mediaeval History (1923-27, bibl.) ; Cambridge Modern History (1901-12, bibl.) . It is neither possible nor useful to indicate all the documents and works relating to all the questions dealt with in the present article ; they can be found in the bibliographies annexed to each of the articles to which they refer. It is sufficient to indicate certain general works. They are, in addition to the Cambridge histories above cited: Th. Lindner, Welt geschichte, 8 vols. (1901-14), a clear, judicial and well-informed account; Periods of European History, 8 vols. (1893-1901) , each volume by a different author, a good popular account ; E. Lavisse et A. Rambaud, Histoire generale du IVe siecle a nos fours, 12 vols. (1894-19.2, with bibl.) , written by a large number of authors of varying ability.

For history after 1815: A. Stern, Geschichte Europas seit den Wiener Vertragen von 1815, bis zum Frankfurter Frieden von 187r, Io vols. in three series (1894-1924) , the most complete and scientific account; C. Seignobos, Histoire politique de l'Europe contemporaine, 2 vols. (7th rev. ed., 1925-26), deals with the period 1814 to 1914 (detailed bibl.) . For England, the Cambridge History of British Foreign Policy, 3 vols. (1922). On the recent period, G. P. Gooch, History of Modern Europe, 1878–r919 (1923).

For the post-war period the chief documents are collections of documents from archives, for the most part published by different Governments and accounts by statesmen or generals, published in the form of notes, memoirs or correspondence. The enumeration of such documents and works will be found in the bibliographies attached to special articles relating to the World War, Versailles, and the League of Nations. (C. SE.) Among recent events of European importance were the with drawal of French troops from Germany in 193o ; the economic crisis which developed in 1931; the rise of National Socialism in Germany under Adolf Hitler, and Germany's defection from the League of Nations in 1933 ; Russia's admission to the League in In 1935, Germany's rearmament, and failure of the League's Sanctionist policy to prevent Italian conquest of Abyssinia; and in 1936 Germany's occupation of the demilitarized zone of the Rhineland, and the outbreak of the Spanish civil war.

It is a curious and regrettable fact that much less comprehen sive information is available concerning the industries of Europe than about those of more developed industrial areas of the world. Thus it is easier to obtain a picture of the state of in dustry in North America, Australia, New Zealand or South Africa than it is to follow the sequence of events in the continent where modern industrial organization began.

Although Europe is the cradle of modern industry, and looks to North America and Oceania for so large a proportion of her food supply, actually a much larger proportion of her population is engaged upon agriculture and fishing than in either of these two areas. There are indeed only five countries in Europe—the United Kingdom, Germany, Belgium, Holland and Switzerland— where industrial workers and miners outstrip in numbers the agri culturists. Indeed, so far as the daily activities of her citizens are concerned, England and Scotland are the only European coun tries where industry plays an overwhelmingly important role. In England and Wales 47.2% of the total population are directly dependent on industry and mining and only 6.8% on agriculture and fishing (1921 census) ; in Scotland the comparable figures are The first fact brought out by these figures is the magnitude of European production even after taking into account that most of China's agricultural output is omitted ; the second is the decline in her position since 1913. This decline, moreover, has been greatest exactly in those industries, coal-mining and metallurgy, upon which her prosperity in the 19th century was so largely based. In textiles, thanks to the development of artificial silk manufacture, she has nearly maintained her position; in chemi cals, as a result of the very rapid progress achieved in the manu facture of azotic fertilizers, she has improved it; but on balance her contribution to the total value of the output of the materials considered has appreciably diminished.

These figures must not, of course, be interpreted as giving Europe's contribution towards total industrial output. They relate either to the products of the soil or subsoil, such as cereals, flax, coal, etc., or such crude or partly manufactured articles as pig iron, wood-pulp, artificial silk yarn, etc. Nor must it be presumed that she is necessarily poorer because her share in the world production of these foodstuffs and raw materials is smaller than it was. Actually her index of raw material production was slightly higher in 1925 than in 1913. The change in her relative position was due to the rapid progress achieved elsewhere, as is shown by the following figures: 91.5, the shipbuilding index 71, that for cotton 78.8, that for tobacco 130.8, for paper 145.8. In France the general industrial index in 1926, owing to the export premium which arose from exchange depreciation, stood as high as 125, while the metal lurgical index, which was appreciably higher than in most other European countries, was well below the general average at 113, and textiles were as low as 94. In Sweden in the same year paper" averaged 162, the chemical industry 144 and all industries 123. In Russia, in the commercial year 1926-1927 the heavy industries averaged 86 and the light 119.

Such data as exist for the whole of Europe give similar results. The recovery and development of the newer and smaller indus tries have been much more rapid than in the case of what were considered the major European industries at the end of the 19th century :— In 1925 many countries in Europe were still suffering from the effects of inflation or the commercial depression which fre quently follows on currency stabilization. In 1926 British industry was prostrated by the protracted coal dispute. In spite of these temporary difficulties production of basic products was during these two years just about at the pre-war level. But in North America it had increased by over a third and the net value added in manufacture by very considerably more. After the autumn of 1926 a rapid advance was made in Europe, well beyond what had ever been achieved previously. But in the interval between 1913 and these later years a very great change had taken place in the relative importance of different industries—a change which is illustrated by the indices for textiles and wood-pulp on the one hand, 143 and 154 respectively, and those for fuels and metals, which were only about 90. To some extent these changes are typical of what had been happening elsewhere. Thus the world fuel and metal indices are much lower than the others given. But European industry has undergone and is undergoing a change which is in many respects exceptional. The competition of coun tries more recently industrialized, changes in commercial policy, new scientific discoveries and a number of other factors have weakened the demand for the products of what were formerly her basic industries—coal-mining, heavy metals, shipbuilding, cotton spinning, etc., and directed capital and labour into other channels. The magnitude of this change can be gauged to some extent from the individual indices of certain countries and by splitting certain of the indices given above into their component parts.

Not many countries supply current and complete information concerning even their leading industries, but the tendencies of trade in Great Britain, France, Sweden and Russia can be traced. Thus, in Great Britain in 1927 the iron and steel index averaged In most cases the year 1925 has been chosen as more character istic for Europe than 1926. Since that date there has been a very rapid development in certain countries, and by 1927 Euro pean production of coal and raw steel was over ioo per cent of that in 1913. But complete later figures are not available and those given bring out very clearly the character of the changes which have been taking place. All the heavy industries have suffered either from absolute weakening in demand or from over capitalisation, an excess of plant laid down for war needs. The general service textiles, cotton and wool, owing to somewhat dif ferent causes, have suffered likewise. On the other hand new industries have grown up and industries which were previously of minor importance have greatly expanded. The tendency for lighter goods to replace the heavier, and for the more expensive the cheaper, is illustrated to some extent in the table. But, in fact, the movement is more radical and comprehensive than is suggested by the figures quoted. Thus, not only have artificial and natural silk replaced cotton and even wool to some extent, but within the cotton industry finer counts are being spun and in the woollen more merinos and crossbreds and less shoddy and coarse wool are employed. Similarly in the metallurgical and engineering industries, while the heavier branches have suffered, the manufacture of lighter machinery has developed and the motor-car industry has made vast strides. The internal combustion engine has for many purposes displaced the steam engine ; alumi nium has displaced cast iron for hollow ware; knitted goods have displaced woollen cloth, etc.

Of the recent technical changes perhaps the most revolutionary are concerned with the means of transport and the electrification of industry. Europe has directed large amounts of capital which might previously have been utilized for railways or other pur poses necessitating the use of the products of the heavy metal industries to the construction of roads and is gradually substitut ing electric power for the direct employment of coal as fuel.

The Most Prosperous Industries.—But during the years im mediately following the armistice, Europe was busily engaged in repairing war damage, and much capital was sunk in the improve ment of land, the reconstruction of towns and villages and the re-equipment of factories. There has thus been a greater expendi ture on capital account than the bare statistics of basic industries portray. It remains nevertheless true that the industries which have prospered the most, apart from a few exceptions are rather those manufacturing goods for immediate consumption—the motor-car industry, hosiery, the manufacture of boots and shoes, of confectionery, of tobacco, of paper, etc. A number of factors have contributed to this result. During the years immediately succeeding the war, the national income of most European coun tries was reduced, and less was available for saving. The hazards of war and the storms of inflation weakened the will to save. The change in the distribution of wealth in favour of unskilled labour at the cost of the landlord and the middle classes hindered capital accumulation. Further, the international flow of capital was checked by currency instability. It is not necessary to deal here with all the complications to which inflation and deflation gave rise. From 1918 to 1925 unsound monetary conditions were without doubt the most important of all the hindrances to Euro pean industrial recovery. They had, however, one secondary effect which is likely to prove of longer endurance, for they contributed in a number of ways to the erection of those tariff walls which have helped to divide Europe up into a number of more or less water-tight compartments. The economic national ism which has characterized post war commercial policy has fur ther enforced the tendency in favour of the development of the smaller and newer industries. The endeavour of each State to make itself economically independent has led to the erection of new plant in a number of markets which were previously supplied from abroad. Thus has there been a double shift in the centre of grav ity : first, away from the staple industries towards new activities, and secondly, away from the large existing agglomerations of plant and equipment towards new plant in less highly developed coun tries. Both tendencies have resulted in much existing plant be ing left inactive. Other influences beyond European control have worked in a like direction. Thus, the growth of industry in the countries in which the raw materials are found, stimulated by the war and fostered by tariffs, has weakened the extra-European de mand for many and more especially for the coarser products of European factories. A particularly striking example of this phenomenon is afforded by cotton spinning; Japan and the United States consumed in the commercial year 1926-27 about 32 million more bales of raw cotton than immediately before the war, and Europe about 1- million less. But while Japan, China, India and Brazil are able to meet their needs in coarser cotton products to a much greater extent than heretofore, the quality of European production has improved and its consumption of fine Egyptian cotton risen.

European industry has been affected, then, by lack of new capital and in certain directions excess of existing plant, by the vagaries of currencies and of taste, by the impetus which the war gave to the industrialisation of countries which for a time were unable to satisfy their needs in the markets on which they had previously relied, by tariffs, prohibitions, transport difficulties and all the other impediments to trade on the construction of which so much ingenuity has been spent. There has been a process of disintegration and new growth. But simultaneously there has been a tendency towards reintegration. The war promoted, and indeed rendered imperative, collective bargaining between the State and industries whose products were required for war needs, and thus stimulated the formation of industrial associations in all belligerent countries. The peace treaties in many cases divided the members of these associations from one another by new lines of frontier. The difficulties of the situation forced the leaders of industry to collaborate in seeking a solution of the problems which arose. Modern European industrial organisation is thus characterized by the concomitant growth of industries new in kind and in place and the association of industries, old and new, into powerful international combinations.

Nature and Volume of European Trade.—The attempts made by the great majority of European countries in post-war years to foster domestic industries have inevitably affected both the composition and the quantum of European trade. The pro portion of the total goods produced which are exchanged interna tionally has diminished despite the fact that with the foundation of new States the number of trading units has increased. But the continent as a whole is necessarily dependent on outside sources of supply for many of her raw materials and is not self sufficing in foodstuffs. The changes which have taken place in commercial policy therefore have not been sufficient seriously to modify the essential characteristics of her international trade. Europe remains necessarily a buyer of raw products and seller of manufactured goods. In some respects recent scientific progress has rendered her less dependent on foreign supplies; thus arti ficial silk is manufactured from indigenous timber, nitrogen is obtained from the air of Europe instead of the deserts of Chile, and the enormous capital expenditure on roads has necessitated the import of no raw materials from extra European lands. But on the other hand the demand for petroleum in which she is not self-supporting, of rubber, of vegetable oils and fats has greatly increased and with the growth of her population her purchases of bread-corn have likewise gone up.

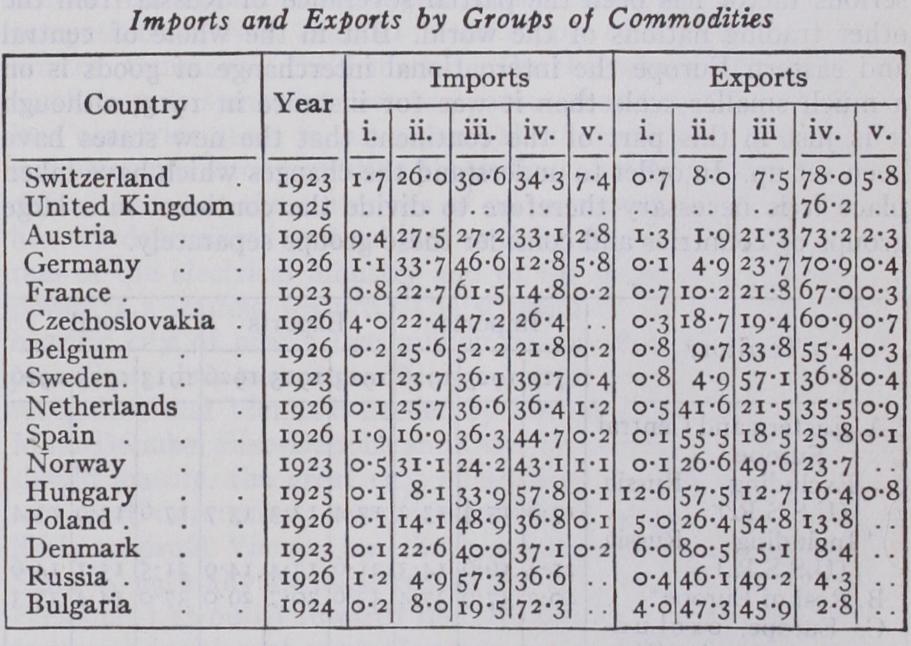

The composition of the trade of the individual countries varies widely and roughly in accordance with the occupational division of the population illustrated above. A number of countries pub lish figures of their trade divided into five large groups of products, namely, (i.) live animals, (ii.) articles of food and drink, (iii.) ma terials raw or partly manufactured, (iv.) manufactured articles, (v.) gold and silver. These countries may with advantage be ar ranged in the order of the relative importance of their exports of manufactured goods.

The selection of countries given is sufficiently characteristic of Europe as a whole to bring out the essential facts and to throw in relief the devotion to industry in the north and centre of Europe, and the importance of agriculture in the east and south-east. The imports of Europe are much more evenly spread amongst the second, third and fourth groups than are the exports. A third of the imports of Switzerland, one of the most highly in dustrialised countries in Europe, consists of manufactured ar ticles, and over a third of those of the Netherlands and Sweden. This contrast between imports and exports is of course an almost universal phenomenon. Countries, like individuals, tend to earn their income by devoting their attention to a restricted number of activities and to spend it on a wide range of objects. But as a characteristic of European trade it is of vital importance. For as industries develop in other parts of the world, Europe's prosperity is necessarily dependent upon the demand by manufacturing States for manufactured goods. Her trade, as her industry, is ac cordingly tending to concentrate more on highly finished goods and articles of high value demanding an exceptional degree of skill in the process of their manufacture.

Exports of coal, of unbleached cotton piece goods, of railway material, have shrunk and British trade has been particularly adversely affected. Both in the United Kingdom and elsewhere the products of the newer industries, of the most expensive goods, of luxury goods, have increased their importance. Thus manu factures of silk, paper, motor cars, scents and soap constitute an increasingly important share of French exports; electro-technical goods of German exports; silk piece goods, fine cotton tissues and motor cars of those of Italy; diamonds and plate glass of those of Belgium. The examples are selected almost at random. The tendency they illustrate is common to nearly all the more ad vanced industrial States of this continent. It has been intensified by the war, but is nevertheless a natural development. It was to be expected that the power of countries beginning on an industrial career to compete with Europe should have been greatest in re spect of the coarser grades of goods. The advantage they derive from cheaper labour or cheaper raw materials could only be countered by methods of mass production—methods whose suc cess is greatly dependent on a large home market. But European markets are fenced about with customs, tariffs and with a few im portant exceptions Europe produces relatively short lines of goods intended to meet the needs of a medley of consumers in all parts of the world and designed to penetrate through what gaps may be found in the tariff walls which have been erected. Further, as all continents in the world grow in wealth, the demand for su perior European products mounts automatically.

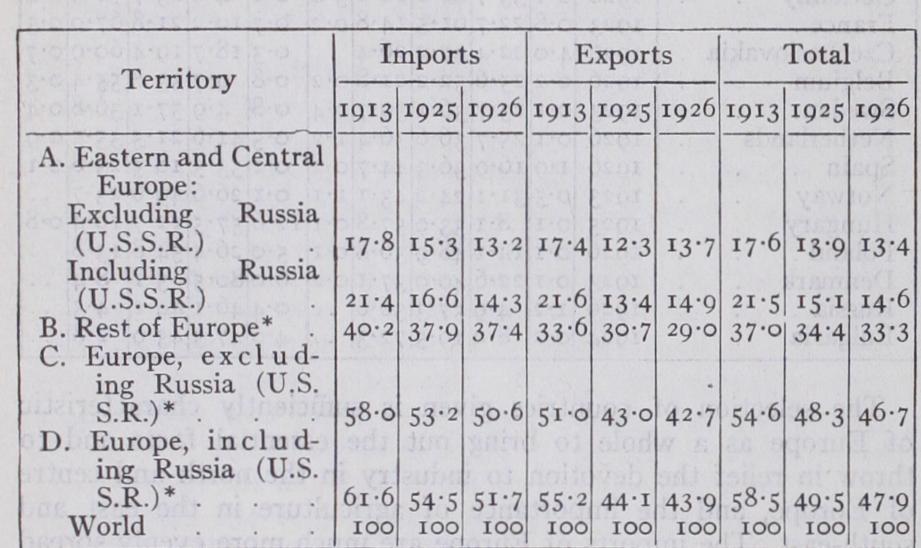

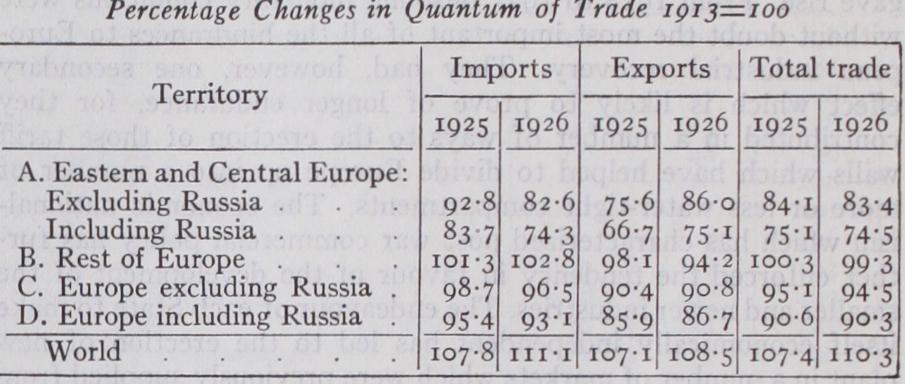

Before the war Europe probably accounted for over 6o per cent of the total trade of the world. In 1926 her share had fallen to under one half. This diminution of her importance has been due in part to an absolute reduction of the quantum of her imports and exports and in part to the very rapid development of the far east and the United States of America. Within Europe the most serious factor has been the partial severance of Russia from the other trading nations of the world. But in the whole of central and eastern Europe the international interchange of goods is on a much smaller scale than it was for instance in 1913, although it is just in this part of the continent that the new states have been set up. In order to understand the changes which have taken place it is necessary therefore to divide the continent into large groups of countries and consider these groups separately.

*Excluding the Netherlands, owing to incomparability of pre- and post-war statistics. The inclusion of the Netherlands would raise the percentages for Europe, including Russia, in 1925 and 1926 to: imports and 53•2 ; exports 45.3 and 45.2 ; totals 5(3.8 and 49.3.

While Europe's share in world trade has fallen off that of North America has risen from 14% in 1913 to 19% in 1926 and that of Asia from 12% to 17%.

Europe's Share of World Trade.—The change which has taken place is, however, more profound than might at first sight be believed. Europe's share in world exports has contracted more than her share in world imports. In 1913 the excess of imports over exports represented very largely goods obtained in payment for the interest owed by countries to which Europe had lent capital. During the war much of that capital abroad was lost or sold for goods required for immediate war-time consumption, so that Europe's claim on other parts of the globe was seriously dimin ished. By 1926 the position had been reversed and many Euro pean countries were borrowing from the United States of America and paying interest on previous loans. Their borrowings were however very much greater than their interest payments, exceed ing them probably by some f i oo,000,000. The excess of imports over exports in that year therefore was composed largely of goods purchased out of the proceeds of capital borrowings. It may be expected that within a relatively short space of time Europe's borrowings will fall below her obligations on account of interest and amortisation of debt and that in consequence her exports will increase relatively to her imports, and both the direction of her trade and the average level of her prices profoundly modified.

Although there is no reason to believe that the net production of European industry is lower than it was before the war, the quantum of her trade, if that term may be employed to express volume in terms of stable values, would appear in 1926 to have been still about i o % less than in 1913. The following figures show the relative position of the same groups of countries as were em ployed above: Russian trade is growing, but in 1926 was still less than half of what it had been in 1913. With the gradual restoration of settled conditions in the other countries of central and eastern Europe trade throughout the whole of this area steadily develops —impeded though it is by high tariffs and frequent changes in rates of duties. The rest of Europe by 1926 had just about got back to the pre-war level, a proof, since foreign trade has become less important than domestic, that the total production of goods had risen above that level. The neutral maritime countries, Den mark, Norway, Sweden, Spain, etc., have achieved the greatest progress; and the first three countries, with Holland, have pursued the most liberal commercial policy. (A. Lov.) The modern period was inaugurated by the exploitation of coal and iron for steam-driven industry, England for long leading in this development. In the last quarter of the 19th century the predominance of British industry was strongly challenged by Belgium, Germany and the United States of America, and with the coming of the loth century, electrical power, whether from waterfalls or from coal and the use of gas and oil engines dimin ished England's initial advantages seriously. The mid-Victorian form of the doctrine of Free Trade, with its consequences of high-specialization on the part of different countries in different activities, was not attractive to Continental States anxious lest economic dependence upon neighbours or possible enemies might interfere with political freedom. The idea grew up of States pro ducing within their borders as much as possible of the manu factured goods they need, and developing an export trade in cer tain industries in which they might have special advantages. The repercussion of this movement upon Britain has been a marked feature of British life in the last ten years, during which efforts have been made in many industries to safeguard the British markets for British products. The conflict between the idea of a British market preserved for British goods and the idea of Britain as a centre of large scale industry for export purposes is one of the standing problems of British life; and solutions are sought by compromise rather than by planning on one or other line.

The coal and iron industries of Europe have developed a zone of dense population along the northern bases of the central hills of Europe, from Flanders to Poland, and in that zone many great industrial centres have grown in what had already long been famous cities, often at the exit of valleys from the broken lands of central Europe. The greatest coal producers, in sheer quan tity, are Britain and Germany, half the German production being lignite, formerly considered inferior but now recognized as of value for special purposes. France, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Russia also produce large amounts of coal, and Spain, south-east Holland, Austria, Hungary and Yugoslavia a certain amount. Quantities of less than three million tons per annum are produced in a number of States. The development of coal mines in the Belgian Campine and in Dutch Limburg, the open ing of the Kent coalfield and the development of the Doncaster area in England, and the rehabilitation of the French coal mines after 1914-18, are outstanding recent features.

The production of iron was at first predominant in England, but the situation changed, especially with the invention of meth ods for extracting the iron from the minette of Lorraine, which has now become the chief source of the metal on the Continent, Europe, as a whole, being behind the United States of America in iron production. With the re-entry of Lorraine into France that country has become the leading producer of iron in Europe, with Luxembourg and England a long way behind. The change of political frontiers has reduced Germany to a minor position in iron production, though she has the coal and the skill for the industry. Iron production in Sweden remains important, thanks to the superior ores found there. Spain, Austria and Czecho slovakia produce a certain amount of iron, and so does Russia. The large iron industry in Belgium depends mostly on Luxem bourg for its raw material, and international co-operation between Germany and France is of the utmost importance to the Ger man ironworks. Vein-minerals, especially copper, are produced chiefly in the Iberian peninsula and Germany, as also are lead, manganese and zinc. Austria is also of some importance here. Some gold and platinum are produced in Russia, and silver in Germany, but the Continent is not rich in the precious metals. Salt has long been of economic importance, indeed many a pre historic site of the Late Bronze or Early Iron age is near salt and seems related to salt supplies. The regulation and taxation of salt supplies have exercised Governments throughout the his toric period, and this attention on the part of rulers demonstrates its special value to mankind. Europe is specially fortunate in having large salt supplies, which are specially important in Eng land, Germany and Poland. Potash compounds are obtained in large quantities in central Germany, and also in France now that the potash deposits of Alsace are within that country once more. The old predominance of Britain in the textile industries has gone. Customs boundaries in Europe have multiplied, and many States are trying to develop these industries for themselves. Moreover, the introduction of wood pulp industries, both for artificial silk and for paper, has given advantages to countries with forests for pulp and waterfalls for power, features which often go together. Further, Holland, as a neutral in the war of 1914-18, has gained very greatly in industrial importance, espe cially in the making of textiles (both cotton and artificial silk). Italy, with long experience of natural silk, leads, in Europe, in the production of artificial silk, though its total is far below that of U.S.A. Germany and England follow, and France, Belgium and Holland also produce the material largely, the production of the two latter being remarkable for the size of the countries.

Motor-cars, oil- and gas-engines, and the use of electrical power, have altered the distribution of the manufacture of fine machinery, and south Germany, Switzerland and north Italy have profited specially in this sphere. The spread of rubber industries is another recent phenomenon. The term chemical industries has come into use to cover a large range of works based upon appli cations of chemical science working upon mineral salts, vegetable oils, and a variety of other materials. The high development of scientific education in Germany has given that country a leading place in chemical industries, but Britain has organized herself in this matter and in that of the production of dye-stuffs in the last few years, and many countries are taking part, in varying measure. The growth of industries in ports to which are brought copra, palm oil, earth-nuts, rubber, etc., from the equatorial regions is a notable feature of this century, while the supply of electric power has promoted the distribution of industries along railway lines, as west of London, not necessarily near coalfields.