Este

ESTE, town and Episcopal see, Venetia (anc. Ateste, q.v.), Italy, province of Padua, 20 M. S.S.W. of Padua by rail. Pop. 11,490 (town) ; 13,836 (commune). It lies 49 ft. above sea-level below and south of the Euganean Hills. The Adige ran close to the town until A.D. 589 but is now 9 m. S. of it. The external walls of the castle still rise above the town on the north. For its mediaeval history see above: ESTE (family of).

Archaeology.

Este was known to the Romans as Ateste and there are remains of Roman building. It has been reserved for the archaeologists to discover that Este was the chief centre of civilization in eastern Italy north of the Po for Boo years before the Roman occupation. A sacred precinct of the Venetic goddess Rhetia has been found here, and boundary stones of 135 B.C. divide the Ateste territory from that of Patavium.To understand the prominent role played by this half-forgotten city it is necessary to understand its extraordinary geographical history. At the present day the Adige flows eight miles to the south of the town, but up to A.D. 589, when its course was sud denly changed by a catastrophic flood, the turbulent river washed the very walls. Vineyards and orchards, which now cover the whole countryside, were only planted in the Middle Ages, and actually hide a long line of sand-dunes in which the ancient ceme teries are situated. In Roman and pre-Roman days the place was practically a seaport, with almost the same outlook and natural advantages as the famous Adria at the mouth of the Po. Conse quently the Atestines were so placed that they could cultivate a seaborne commerce, while at the same time they could travel by easy land routes round the head of the Gulf of Venice to Istria. On the south they were guarded by the broad and formidable stream of the Po, which effectually protected them against all attacks from that quarter. The Etruscans never penetrated into Venetia, and the Romans themselves never conquered the country, but peacefully occupied it under agreement with the inhabitants in 184 B.C. Down to the beginning of the Christian era the people of Este retained their own language and customs.

These Atestines—to use a geographical term which avoids all controversy as to the tribal identity or priority of Veneti, Euganei, or others—must be regarded as a branch of the same stock as the Villanovans. They were perhaps the latest of the cremating in vaders to cross the Alps and who settled in northern Italy. In deed, some Italian archaeologists have attempted to establish a 1st Atestine period contemporary with the ist Benacci of Bologna; but the supposod traces of it are extremely slight, so that it is only with the beginning of the so-called second period that, there is enough material for adequate treatment. This 2nd Atestine period may be dated 95o B.C. to 500 B.C. That is to say it begins at the same time as the 2nd Benacci of Bologna and lasts down to the end of the Arnoaldi (see "VILLA\ OVAN S") . The third period may be placed at 500 B.C. to 350 B.C., at which latter date the Gaulish invasions put an end to all the flourishing arts and industries of northern Italy. When these revived again to some extent under the Romans they had lost in Este, as in other places, a great deal of their individuality, and tended to become merged in the general complex of a civilization from which more of the local character had disappeared.

The close cousinship of the Bolognese Villanovans and the Ates tines is proved by the complete identity not only of the burial rite, cremation, but of the forms and details of their graves. Moreover the contents of these graves are to a great extent iden tical during the whole of the second period. Amongst both peoples are found weapons and implements of the same type; there are the same bronze girdles, the same patterns of bracelets and neck laces, the same ornaments of amber and glass. Even the numer ous varieties of fibulae are identical in the two regions and follow precisely the same steps of evolution. But with all this similarity there are also a good many points of difference ; objects are found at Bologna which do not occur at Este and vice versa. It is par ticularly in respect of its metal work and the production of large bronze vases, or situlae, that Este shows its independence from the very first. The technique is the same as the Bolognese; casting was not used, but thin plates of copper or bronze were hammered out by hand and bent over to the required shape, after which they were fastened in place by rivets, often so emphasized as to form a simple ornamental motive. Large vessels made in this way occur very early in the second period, already assuming the form of the situla which was used as the ritual ossuary for hold ing the cremated ashes. On the other hand the large water jars of bronze which are among the best Bolognese products after the 8th century B.C. do not occur at Este. It is evident that these two great manufacturing centres remained quite separate and in dependent, though exercising a certain amount of reciprocal influ ence upon one another. Each was held in high repute over the whole of Italy and exported its wares far and wide, even beyond the Alps. But the Etruscan motives, which broke through the geo metrical tradition and substituted decorations based on animal life and the growth of plants, did not reach Este before 500 B.C. though they had been gradually influencing Bolognese art for sev eral generations before this.

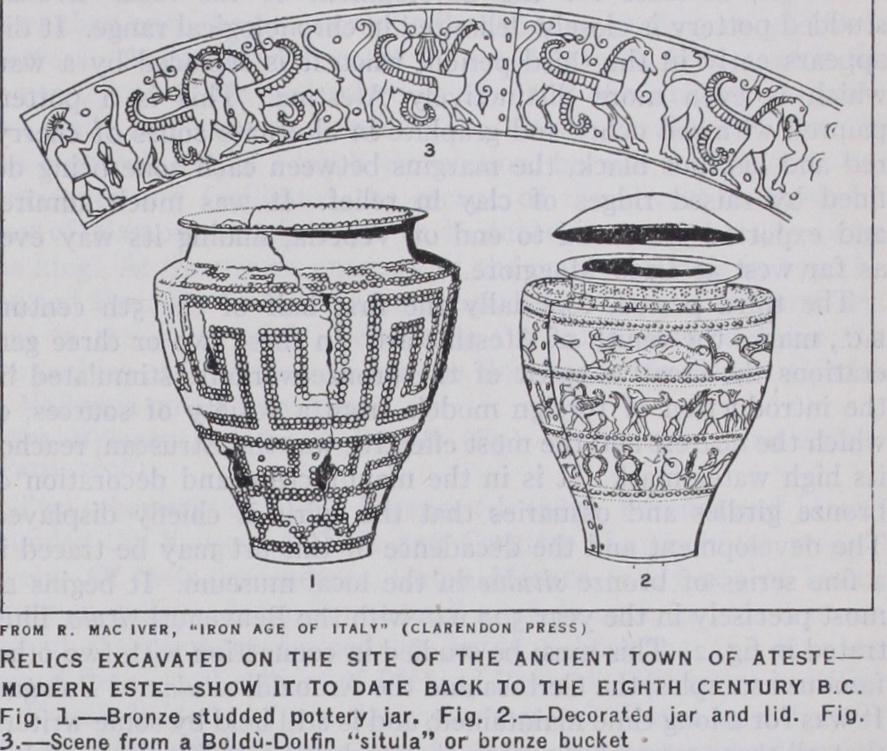

A markedly individual product of the second period at Este is the pottery. This is a black ware, generically similar to the black ware found all over Italy and in many other parts of Europe dur ing the Iron Age, but peculiar in the style of its decoration. The patterns are not incised, but are produced by embedding large studs of bronze in the wet clay before firing. This process results in turning out a very handsome and showy jar ornamented with bold geometrical motives, such as those shown in fig. 1. It is a style obviously inspired by metal-work, the potter deliberately setting himself to produce the effect of repousse ornament in a cheaper and more malleable material. The only other district in which this curious technique was practised is Falerii in central Italy. As the finest and most numerous examples, however, are found at Este, this city must be given the credit, if not for the invention, at least for the development of the idea. Bronze studded pottery is closely delimited in chronological range. It dis appears early in the third period, when it is replaced by a ware which is even more distinctively Atestine. This is a pottery painted with red ochre and graphite in alternate zones of cherry red and lustrous black, the margins between each zone being de fined by raised ridges of clay in relief. It was much admired and exported from end to end of Venetia, finding its way even as far west as Lago Maggiore.

The third period, especially the first half of the 5th century B.c., marks the zenith of Atestine art. In these two or three gen erations the creative spirit of the bronze-workers, stimulated by the introduction of foreign models from a variety of sources, of which the nearest and the most effective was the Etruscan, reached its high water mark. It is in the manufacture and decoration of bronze girdles and ossuaries that the spirit is chiefly displayed. The development and the decadence of this art may be traced in a fine series of bronze situlae in the local museum. It begins al most precisely in the year 50o B.c. with the Benvenuti situla, illus trated in fig. 2. This must be studied in connection with two other famous examples, the Certosa and the Arnoaldi situlae of Bologna. It was for a long time maintained, and is still held by some writers, that all three were produced in the workshops of Este; but of late years the best critical opinion inclines rather to regard the Cer tosa and Arnoaldi situlae as products of Bologna. In any case it is quite evident that the Benvenuti situla reproduces a general scheme of decoration inspired by Etruscan life and motives. The Certosa situla depicts an Etruscan funeral-procession and scenes from the life of the countryside. In the Benvenuti example there are similar scenes, the herdsman with his ox and dog, or the horse that is exhibited by the groom to his master. But with these are such purely Etruscan motives as the winged sphinx, as well as the stock Etruscan pictures of a military procession, a feast and a boxing match. Many situlae of this style were manufactured at Este and they were so popular that they were exported over the Alps even as far as the Danube. Atestine situlae or imitations of them have been found over an area which extends in a half circle from Krain on the east to the Brenner on the west; the most famous specimens are those of Moritzing, Matrei, Welzelach, Meclo, Watsch, Kuffarn and Hallstatt. All these Alpine versions, however, are rather clumsy travesties of the fine Italian originals.

The artistic spirit of Este itself began to degenerate very ap preciably in the 4th century. This can be seen from the situlae of the Boldu-Dolfin graves, which, though they are technically as well made as those of three or four generations earlier, betray a total lack of artistic taste. Instead of the fresh scenes of country life or the pleasant little pictures of cattle, deer and birds which gave a pleasing grace to the bronzes of the 5th century, the Boldu Dolfin ossuaries show only clumsy imitations of fantastic myth ological beasts, taken from the now unmeaning repertoire of a tenth-hand copyist (fig. 3). The artist has been swamped in the progress of mass-production; the Atestine factories had become too successful. Consequently the art of the 4th century B.C. has lost all freedom and individuality. As a factory centre Este was doubtless important down to Roman times, but it contributed nothing of value to civilization after A.D. 400. The student of manners, however, will find much that is interesting in the figurines of the Baratela collection, and the philologist values the Euganean inscriptions of the 4th century A.D. which are to be seen in the museum.