Etching

ETCHING is the process of biting lines or areas by means of acid or some other chemical. By etching generally we mean the process of biting these lines in a metal plate with a view to its being printed from, and by an etching, the print taken from a plate so etched. Lines may indeed be etched on a metal plate which is itself intended to serve some decorative purpose, with no idea of prints being taken from it, but etching of this sort should more properly be treated in connection with decorative metal work and has no significance here. Etching, as above de fined, has this important point in common with line engraving, that the lines which are to appear black on the print are incised as opposed to those in wood engraving which are in relief. The process of printing from an etched plate is, therefore, identical with that of printing from an engraved plate. Etching only differs from line engraving in the process by which the lines are incised; in the latter case, by an instrument of triangular section which scoops a shaving out of the metal; in the former, by chemical action. A print from an etched plate may generally be distin guished from a print from an engraved plate, by the fact that in the former the lines do not diminish or increase gradually in thickness but do so in more or less abrupt stages; that the endings of the lines are square, whereas in the latter they taper gradu ally to an end. These differences are inherent in the different processes. It is obviously impossible to end a line abruptly by means of a triangular gouging instrument, such as a burin; if the burin were stopped suddenly the shaving it forms in its course would be left. In etching, on the other hand, the thickness or thinness of the lines being obtained by successive bitings and each successive biting being comparatively uniform over the plate, a line, which is intended to gradually diminish in size, has (micioscopically perhaps) a form like that of an extended tele scope. Engraving has, of course, been constantly used in combi nation with etching and it is often a matter of difficulty to distinguish between the parts which are purely etched, those which have been first etched and later strengthened by the en graving tool and those which have been directly engraved. A further word should be added on the subject of dry-point. This is merely the process of scratching with the etching needle direct on the plate. In its passage the needle leaves an irregular ridge on either side of the line which it makes (burr) to which the ink adheres, so that a dry-point line when printed has at first a slightly blurred, but rich effect : this burr wears away quickly and the scratched line by itself, when printed, is then faint and meagre. Dry-point, though it is independent of the use of mor dants, is generally employed in conjunction with etching for the richness of its effect.

The number of satisfactory prints which may be taken from an etched plate varies according to the hardness of the metal and the depth to which the lines have been etched. A fine line on copper plate may be almost obliterated after 200 or 30o impres sions: a dry-point line will, as has been indicated, lose its charac teristic effect very much sooner. Some of the prints taken from Rembrandt's plates so years ago are almost, though not quite, as good as those taken during leis lifetime.

Etching, like engraving, was probably invented north of the Alps, and it is in Germany, France and England, and above all the Netherlands, that the greatest triumphs of the process have been achieved. It will be most convenient in a brief summary of its history to deal with its progress in the Teutonic countries from its beginning to the end of the 17 th century, and then to return to Italy, France and Spain. As a means of decorating metal, particularly armour, etching was practised at least as early as the middle of the 15th century. It seems probable that, as the earliest engraving was the work of goldsmiths, so the earliest etching is to be credited to the armourers. The idea of printing from such a plate they no doubt borrowed from the goldsmiths. The first etching, to which an approximate date can be given, is a portrait of Kunz van der Rosen by Daniel Hopfer (working which a rather complicated line of reasoning as signs to the year 1504 or earlier. Daniel Hopfer was one of a family of armourers working in Augsburg, but was an artist of much originality. Hans Burgkmair the elder the dominating personality of the Augsburg school, and on whom the Hopfers largely depended, executed a single etching, no doubt learning the process from the lesser artists. The earliest etching which actually bears a date is one by the Swiss goldsmith, soldier and draughtsman, Urs Graf (d. 1529), of the year 1513, most probably done at Basle. Albrecht Durer (147 r-1528), with the eagerness for experiment which characterized him, tried etching, but apparently found it an unsympathetic medium and after a few experiments gave it up in favour of engraving. His half dozen etchings dated between r 5 r 5 and 1519, impressed though they are with that great artist's personality, are among the least satisfactory of his reproductive work. Iron, the metal used in all these first attempts, did not allow of much delicacy, and the re sult, compared with line engraving on copper, for which it was regarded as merely a less laborious substitute, unsatisfactory.

However, it was a new process which everyone must try out for himself. In Holland Lucas van Leyden , who prob ably learnt the process from Diurer during the German's visit to the Netherlands in 15 2 0-21, etched a few plates. These are technically superior to Diirer's, and of importance as probably the first examples of the use of copper for etching, which made it possible for line engraving to be used in combination with it. The fine portrait of Maximilian which Lucas van Leyden made in 1521 is an example of this combined use of etching and en graving, the whole of the emperor's face being finished with the burin. Dirick Vellert at Antwerp (working 1517-44), an artist of delicate accomplishment, uses a technique much resembling Lucas's, though the majority of his works are engraved. Nicolas Hogenberg of Munich (working 1523-37), whose artistic career was passed at Malines in the service of Margaret of Austria, was one of the first northern artists to use etching with rapidity and freedom, and his frieze of the entry of Charles V. into Bologna in 1530, in a number of plates, is important from its size as well as from its subject. Frans Crabbe (the Master of the Crayfish; d. 1553), who was associated with Hogenberg, also followed his example in etching, but his work is unequal in quality.

Durer's followers in Nuremberg, Hans Sebald Beham (15oo 50) and Georg Pencz (150o-5o) etched only a few plates, for the most part in the years immediately following Diirer's experi ments. Albrecht Altdorfer (about 148o-1538) of Ratisbon, also no doubt impelled by Diirer's example, tried his hand at etching as early as 1519, and later used it for the first pure landscapes produced. Augustin Hirschvogel ?) and Hans Sebald Lautensack (working 1524-63) in Vienna followed Altdorfer's example in landscape, but without quite the freshness and charm of its originator. The only succeeding etcher of importance in Germany is Jost Amman (1539-91), who worked at Nuremberg.

In the Netherlands, line engraving usurped the field in the latter half of the i6th century and comparatively little etching was done. Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen (15oo-59), the court painter of the Emperor Charles V., had etched a number of plates. He is probably the earliest example in the Netherlands of the painter, with no training as an engraver, turning his hand to etching. His plates, some of them of large size, are still executed in rather a formal style but are extraordinarily fresh and effective. Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder (c. 1521-1604), of Bruges, was the author of a charming series of small plates illustrating Aesop (1567), which are etched with a delicacy and sensitiveness hardly equalled by Adrian van Ostade or Hollar. Gheeraerts spent the latter part of his life in England, where he issued further etchings, the first to be published in that country. Hieronymus Cock (15 i o? 70), the publisher, did some admirable landscapes of the conven tional type, and the great Pieter Bruegel (152 5 ?-69) and Frans Floris (c. 1517-70), the fashionable painter of the time in Ant werp, each etched one plate, while Hans Bol, the landscape painter and draughtsman of Malines (1534-1593), within rather narrow limits, was an etcher of considerable charm. Paul Bril of Antwerp (1554-1626), who passed practically the whole of his life in Italy, is chiefly interesting as a link between the conven tional Italian landscapes evolved in the Venetian school and the native style of the Netherlands. Hercules Seghers (c. an artist of real originality, is dependent on Bril's theatrical con ventions, while still in contact with Rembrandt. Seghers's curious experiments in printing and colouring by hand, though they can not be actually classed as colour prints, as he never attempted to print with more than one colour at a time, are interesting and unique. Esaias van de Velde (c. 159o-1630) and his brother Jan (c. 1596-1641) are the earliest of the Dutch etchers who looked to Holland for the subjects of their landscapes. Simple, almost meagre in technique as their etchings are, they render with a naive charm and directness the views in their native land. Wil lem Buytewech (c. 1585-1625), from whose drawings the Van de Veldes worked, is well known as a painter of individuality, which appears in his few etchings.

The enumeration of the names of these few etchers who worked in the Netherlands at the end of the 16th and beginning of the r 7th century, leads up to, but does not explain the importance, which, with surprising suddenness, the medium attained in the hands of Rembrandt Van Rijn (1606-69), and Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641) . The latter's achievement, remarkable as it is, is limited in scope and quantity, but as it precedes Rem brandt's in point of time will be dealt with first. The famous "Iconography" was planned by Van Dyck as a series of engraved portraits of contemporaries eminent in the arts. Etching was to play only a subsidiary and preliminary part in it, and, in fact, it was only for 18 of the too plates issued that Van Dyck himself executed preliminary etchings. The rest were engraved in line by the professional engravers trained in the school of Rubens. These 18 etchings, too, were subsequently finished by these same engravers, and it is only in the very rare impressions taken from these plates, before the additions were made, that Van Dyck can be appreciated as an etcher. His methods are quite independ ent of previous practice and of the conventions of line engraving. No doubt, the fact that he regarded the etching as merely pre paratory, was partly responsible for their freedom from precon ception. His natural instinct for form, aided to a certain extent by the example of Barocci and Italian etchers, led him straight to the secret of etching which we have since come to recognize is the essential one. His methods seem so obvious, that it is difficult as well as superfluous to try to describe them. Economy of line and contrast between this and the whiteness of the paper is the main secret. The heads stand out realized with quite ex traordinary force and precision. There is no use of dry-point or of tone on the surface of the plate: the effect is gained by clean draughtsmanship.

Van Dyck's example as an etcher had comparatively little im mediate effect; it is in modern times that his influence is most apparent. The great influence which he excited during his life time and for the rest of the 17th century was on portrait engrav ing, through the "Iconography" in its completed, engraved state.

Rembrandt's importance as an etcher is greater than Van Dyck's in proportion to the superiority and greater versatility of his genius. The number of his etchings, varying indeed with the trend of criticism from the 14o accepted by Prof. H. W. Singer to the 30o allowed by Prof. A. M. Hind, is at all events considerable, and comprises every variety of subject, scenes from the Old and New Testament, genre, portrait, still life, landscape. In his treatment of each subject in turn, his method is as fresh and untrammelled as was Van Dyck's in relation to portrait. But unlike Van Dyck's, Rembrandt's approach was gradual, and final and complete as each successive achievement appears to us, to him nothing was satisfying or final. The earliest dated etching, the small portrait head of his mother of 1628, is a masterly achievement, reflecting with great exactness the style of por traiture of his early Leyden period. Between this date and about 1632, his style undergoes no material change, though his etchings vary enormously in quality and elaboration. About 1636 the influence of Rubens, apparent in his painting, is correspondingly seen in his etching in a different and lighter chiaroscuro, with a tendency to sharper contrasts in light and shadow. The so-called "10o guilder print" of 1649 (Christ blessing little children) marks the apogee of his next period, in which dry-point plays an im portant part, and where the whole plate is covered with a net work of fine lines, giving almost the appearance of mezzotint. To 1653 belong two of his largest and perhaps his most wonder ful plates the "Ecce Homo" and the "Three Crosses," in the latter of which his feeling for the dramatic moment, his tre mendous power of expressing emotion in terms of chiaroscuro, are triumphantly exhibited. The technique has become slightly less elaborate ; heavy individual lines are more apparent, there is less use of cross hatching and a tendency to model in vertical parallels and a masterly use of the effects of tone left on the surface and of dry-point. In the etchings which follow up to the last-dated one of 1661, there is a further tendency towards the still broader and more drastic treatment visible in his latest paintings, and a more complete reliance on heavily etched line without dry-point. The landscape etchings, most of which belong to the years about 164o and 165o, stand somewhat apart in the comparative simplicity of their aim as studies from nature, with the exception of the most famous, the "Three Trees" of which is as dramatic as any of his subject etchings. The portraits are, for the most part, in the more careful and elaborate tech nique of his earlier period, and perhaps insisted on by his sitters. The greatest are among the numerous portraits he etched from the mirror in every variety of costume and character.

Rembrandt's contemporaries in Holland, except for his im mediate associates and followers Jan Livens (1607-74), Ferdi nand Bol (1618-8o), Jacob (c. 1616-1708) and Philips Koninck (1619-88) and J. G. van Vliet, remain comparatively unin fluenced. Anthonis Waterloo (1609?-1677?), who enjoyed in the r8th century an enormous and exaggerated vogue, has indeed some claims to importance as a landscape etcher, and Alart van Everdingen (1621-75), in his small plates, mostly of Nor wegian scenes, shows a delicate and observant talent. Jacob Ruysdael (c. 1628-82) may claim a place next to, though indeed far below, Rembrandt's as a landscape etcher. His delicate and exquisitely finished etchings are in the nature of detail studies of particular woodland scenes, diversified by still water reflecting the trees. Of the Dutch painters who looked for their theme to Italy, Nicholas Berchem (162o-83) and Karel du Jardin (1622-78) are the best known. Their landscapes included as important parts of the composition human figures and animals, and they serve as a link connecting the landscape with the animal and genre painters. Of the animal painters Paul Potter (162 5 54) is the most famous; of the genre painters Adrian van Ostade (161 o-8 5) . Ostade uses etching with a painter's eye, and knows equally well how to render with extraordinary subtlety the sub dued light of the squalid interior, and the glow of sunlight on a scene of rustic festivity.

The only etcher of note to work in England during the i 7th century is Wenceslaus Hollar 7 ), who was born at Prague but spent the greater part of his life in the British Isles. Of the very large number of etchings which he executed the majority was intended to serve merely utilitarian and topographi cal purposes, but in spite of this nearly everything that he did shows at least a touch of real artistic feeling.

Though etching, as we have seen, was probably invented north of the Alps, it is in Italy that its potentialities as an independent graphic medium were first realized. Francesco Mazzuoli (Par megiano) (c. 1503-4o) in his few plates uses the etching needle not as a substitute for the burin, but with the freedom of the pen. His etchings are obvious reproductions of his masterly but rather facile drawings, which enjoyed a very great contemporary popularity, and he most probably employed etching as a method of satisfying the demand for his drawings. Following his example, most of the great Italian painters thought it incumbent on them to make at least a few etchings. Of Parmegiano's immediate following the Venetian painter, Andrea Meldolla (Schiavone) (d. 1582), is the only etcher of importance, and his work in this direction is almost entirely derivative from that of his prototype. Battista Franco (1498?-1561), the Venetian follower of Michel angelo, did a certain amount of etching, but in a lighter and more formal style, and the work of the other Venetians like Battista and Marco' Angelo del Moro, G. B. and Giulio Fontana and Paolo Farinati, show rather a reaction against the freedom of Parmegiano's style, to which, however, Jacopo Palma the Younger returns with some measure of success. Federico Baroccio of Urbino (15 28-1612 ), in his two or three etchings, works out quite a new and striking method of his own, detailed and careful, but at the same time quite different from the con ventional engraver's style, and a masterly rendering of the pe culiar effects of chiaroscuro at which he aimed in his paintings. Annibale Carracci (1560-16o9), the most brilliant exponent of the so-called eclectic school of Bologna, in his few etchings is less original, but they still have the stamp of a real artistic personality.

In etching, as in painting, the artists of Italy are roughly divided into two schools during the 17th century: the one fol lowing the orthodox teaching of the Bolognese Carracci, the other deriving from Michaelangelo da Caravaggio. The division is no longer a territorial one and the eclectics worked side by side with the "tenebristi" or follower of Caravaggio. This close con tact led by degrees to a mutual influence by one school on the other and the original line of demarcation becomes gradually obscured. Guido Reni an actual pupil in the Car racci school at Bologna, is the most eminent of the eclectic etchers, and his well balanced, delicately sentimental style be came the classic type for most of the etchers in France and Italy during the century. Simone Cantarini and Giovanni Antonio and Elisabetta Sirani are agreeable echoes of Guido. G. F. Barbieri (Guercino) (1591-1666) in his few etchings is more original and shows some Caravaggiesque influence as does Giuseppe Caletti (c. 1600-60). G. F. Grimaldi (1606-8o?) the chief landscape etcher of the school, is conventional and dull. Carlo Maratta (1625-1713) carries cn the Carracci style into the 18th century. The greatest etcher working in Italy in the 17th century is un doubtedly the Spaniard Jose de Ribera (1588-1652). His style, in so far as it is not to be classed as Spanish, is definitely Cara vaggiesque, but his technique as an etcher is partly derived from the Bolognese. The sensitiveness of his outline, which plays an important part in his work, and the sureness with which he knows how to render the changes from brilliant light to darkest shadow, are extraordinary. Ribera's pupil, the Neapolitan Sal vator Rosa (1615-1673), the painter of romantic bandit-infested landscapes, in his etchings, the less pretentious ones particularly, shows some of the charm which we associate with his fantastic world. In Genoa, Benedetto Castiglione (1616-70), whose talent has something in common with Salvator's, is attractive from the grace which characterizes his etchings and interesting from the fact that he was influenced by Rembrandt's work. In Venice, Giulio Carpioni (1611-74) etches with vividness and grace ro mantic scenes in a technique derived from the Carracci. Pietro Testa (1611-5o), who worked in Rome, is an unequal but not uninteresting artist, with a curiously Venetian feeling for light which anticipates Tiepolo.

Little etching was done in France in the 16th century. The frescoes decorating the palace at Fontainebleau executed by Rosso Fiorentino, Primaticcio and their followers, were repro duced in etching by Antonio Fantuzzi, Leonard Thiry and other artists engaged in the work, but these are crude and hasty works. Jean Cousin (d. 159o) is credited with two or three etchings of more merit, and the architect and designer, Jacques Androuet Ducerceau (c. 1510-80) , used etching for his delightful archi tectural compositions with a truly French grace. But with the 17th century and the names of Jacques Callot (1592-1635) and Claude Lorrain (1600-82), France attains a position of real importance in the history of etching. Callot, unlike most of his contemporaries and successors who depended almost entirely for their inspiration on Italian classicism, is essentially and originally French. Technically, his innovations consist in his handling of the individual line, by the thinning and thickening of which exclusively his effects are obtained, but he is also the inventor of a new world of minute fantastic figures, a sort of French stage fairyland. Besides their extraordinary elegance, such series as the grandes and the petites miseres de la guerre, have a point and an emphasis in their narrative which is surprising on so minute a scale. The technique of subsequent etching could not and did not remain uninfluenced by Callot's practice, but his only close follower is an Italian, Stefano della Bella (1610-64) . The French academicians of the grand siecle, Le Sueur, Le Brun and the rest with their ready-made classical formulae had no chance of suc cess in a medium as personal as etching should be, and it remained for Claude Lorrain with his direct reactions to the landscape which he saw around him to produce the only great etchings of the period besides those of Callot. Though his conception of landscape painting was bound by certain theatrical conventions, in his drawings and etchings he approaches his subject directly and at the same time with the true landscape painter's instinct for selection. He is not a good etcher technically; there is some thing fumbling and amateurish in his work, but in spite of these disadvantages, he somehow succeeds in producing landscape etch ings of an extraordinarily moving quality.

The i8th century did not find in etching its most characteristic means of expression. In France, whose artistic preponderance in Europe during the period, was undisputed, line engraving was more extensively and more successfully practised. Etching was to a large extent employed, it is true, but mostly as a preliminary to or in conjunction with engraving, and such mixed productions may more legitimately be classed as engravings (q.v.). Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), Francois Boucher (1703-7o), Honore Fra gonard (1732-1806) and the brothers Augustin (1736-1807) and Gabriel de St. Aubin (1724-80), all practised etching to a limited extent. Jean Duplessi-Bertaux (1747-1813) etched historical scenes largely of republican and Napoleonic times with a spirit and delicacy quite in the tradition of Callot.

It is, however, in Italy and Spain that the great etchers of the century flourished. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo of Venice (1696 1770), whose brilliant decorative painting is the culmination of rococo art, showed as an etcher equal brilliance. His technique, recalling that of Jose Ribera and G. B. Castiglione, is yet en tirely original in its almost complete avoidance of heavy defining shadow and his method of rendering the broad, grey shadows by systems of herring bone and irregularly arranged short lines. His scenes, laid in a brilliant and all-enveloping sunlight, comprise some of the stock i8th century sylvan and Arcadian genre, as well as more imaginative subjects, but treated alike with a pecu liar point and irony. Antonio Canale (Canaletto) (1697-1768), Tiepolo's contemporary in Venice, distinguished as the most bril liant portrayer of his native city, was an etcher of almost equal distinction. His 31 etchings of Venice and the neighbourhood reproduce faithfully the quality of his painting. It is, indeed, remarkable in him and in Tiepolo how their etching is directly dependent on their painting. They seem each independently to have discovered that method of etching extraordinarily compli cated and original, which would most exactly correspond to the essential quality of their painting. In each case the result is not, as might have been anticipated, a lifeless reproductive technique, but a brilliant addition to the repertoire of etching. Giovanni Battista Piranesi (172o-78), the third great Italian etcher of the century, though also a Venetian by birth, worked nearly all his life in Rome. The bulk of his very extensive etched work is archaeological, but his feeling for architectural composition and for the quality of the etched line entitle this work to be regarded from the artistic point of view.

Francisco Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) inevitably finds a place at the beginning of any account of modern art, and indeed his work looks forward into the 19th rather than backward into the i8th century, so extraordinarily fresh and original it is and so free from any of the typically rococo elements which mark 18th century art. Yet technically, Goya derives from Tiepolo (he visited Italy during his youth) and his earliest work in etching, though it reproduces paintings by Velazquez, is very much in Tiepolo's style. But his original compositions, the series of the Caprichos, the Proverbios, the Desastres de la Guerra and last of all the Tauromaquia, show the evolution of an original technique with the use of aquatint for the backgrounds. The mysterious satirical works, the Caprichos and Proverbios, although the exact target at which their shafts are aimed is un certain, are overwhelming in the bitterness and intensity of their satire and the horror of the imagination which they show.

With the notable exception of Goya's work there is compara tively little of interest to record in the field of etching during the first half of the 19th century. It is one of those periods of stag nation which occur before a revival. In England, work of dis tinction, based on that of Rembrandt's contemporaries such as Ruysdael, was done by John Crome (1768-1821) of Norwich, as well as by John Sell Cotman (1782-1842), most of the latter in the process, invented at the end of the i8th century, called soft-ground The names of Thomas Girtin (1775-1802) and J. M. W. Turner (1775-1851), can hardly be omitted in view of their pre-eminence as landscape painters, but their work in etching, masterly as it is, was in neither case intended to be final. Girtin's etchings were preparatory to aquatints and Turner's to mezzotints. Andrew Geddes of Edinburgh (1783-1844) is the author of a number of plates of real distinction, marked by a considerable and intelligent use of dry-point, and Samuel Palmer (1805-81) is a landscape etcher of individuality.

The painters of the "Barbizon" school of landscape in France, Theodore Rousseau (1812-1867), Charles Jacque (1813-1894) C. F. Daubigny (1817-78), J. F. Millet (1814-75) and Camille Corot (1796-1875), all etched. The most prolific and important for his influence on the etchers of the next generation was Jacque, whose style shows the influence of Ostade and the Dutch etchers of the 17th century, while C. F. Daubigny, as an etcher, shows great power and originality. Millet in his plates, executed in a style which resembles that of Ostade's etchings magnified to about four times their original size, portrays those subjects of peasants at work familiar in his paintings, with the same instinctive under standing. Corot used the etching needle only occasionally, but in a manner which, for all its seeming scratchy incompetence, vividly reproduces the atmospheric effects of his paintings. The greatest figure in French etching of the century, that of Charles Meryon (1821-68), stands rather curiously aloof from that of his con temporaries. Precluded by colour blindness from the practise of painting, he is that rather rare phenomenon—an etcher who is not a painter. Influenced by a study of the work of the ad mirable, but comparatively little known Dutch 17th century to pographical and marine etcher, Reynier Zeeman, and obviously, to a certain extent, by Piranesi rather than by contemporaries, Meryon evolved for himself a system of line which, in its clarity and incisiveness, is unrivalled for the rendering of architectural subjects. His reputation, resting, as it does, on a small number of plates of the streets and churches of Paris, might, on the face of it, seem exaggerated, but the extraordinary perfection and in evitability of design which these show seem to create out of a restricted subject matter a formula of universal application.

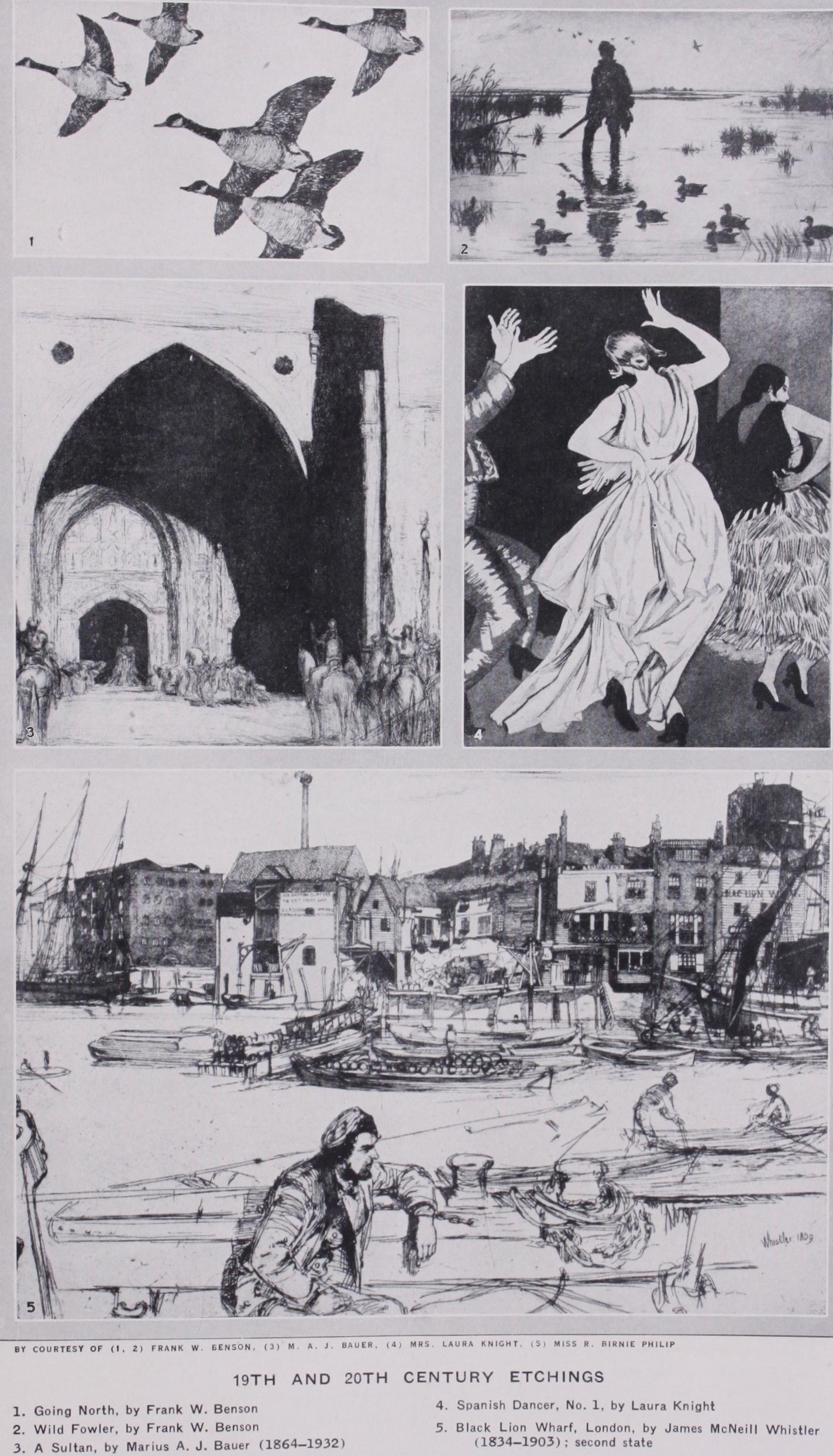

The revival of etching in England in the 19th century was due, in large measure, to the influence of three men of whom undoubt edly the greatest was James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). American by birth, but thoroughly cosmopolitan, a large part of his life was passed in England and it was here that his influence was perhaps most pronounced. His conception of etching, as of art in general, even more than his practise, has had the pro foundest effect. Rembrandt was undoubtedly the chief influence on his etched work. His idea of an etching as an exact and in evitable composition from which no single one of the innumerable lines which go to make it up could be removed or displaced by a hairbreadth, is almost justified by the perfection of some of his exquisite plates. Sir Francis Seymour Haden (1818-1910), Whistler's brother-in-law, though an amateur, exercised a direct influence on English etching even greater than Whistler's, who had little immediate following. Haden was by no means an echo of Whistler : though inspired by him in the first instance, his was too independent a character to allow of anything in the way of imitation. He also went back to Rembrandt for inspiration and etched with an incisive strength and clarity which are admirable, though his work can hardly compare with the greatest. The third important influence on English etching was that of Alphonse Le gros (1837-1911), a Frenchman and first Slade professor of art in London, where most of his life was spent. His was not a talent of extreme originality, but he had a great feeling for, and understanding of, etching and an extraordinary power of assimi lating the methods and thoughts of the great masters.

Whistler had in Theodore Roussel (1847-1926) another French man settled in England, a follower as fastidious as himself who later evolved an original method of colour etching; and in Walter Sickert (b. 186o), an artist of real originality who has since de veloped along his own lines and founded an important school. In the tradition of Seymour Haden may be counted Sir D. Y. Cameron (b. 1865), whose landscape etchings and dry-points are marked by faultless taste and distinction; Sir Muirhead Bone (b. 1876), who has specially developed the architectural theme. The most distinguished pupil of Alphonse Legros was William Strang, whose portrait etching in particular is admirable, but who perhaps fails by a lack of concentration in his powers to convince as a great etcher. The etched work of Augustus John (b. 1878) is the characteristic occasional work of an important painter, in the tradition of the great masters, while that of Frank Bran gwyn (b. 1867) is distinguished by its impressive size and feeling for composition in landscape and architecture. Sir Frank Short (b. 18S7), for many years director of the school of engraving at South Kensington, exercised, after Haden and Legros, the greatest influence on etching, and was himself an etcher of great technical ability, though perhaps better known as the reviver of the process of mezzotint.

The succeeding generation has been extraordinarily prolific in etchers of real distinction, and the first quarter of the 2oth century may well come to be regarded as one of the important epochs in the history of etching. It is a matter of difficulty to class and arrange contemporary achievements, and it will suffice to name a few of the more prominent. As an etcher of landscape as well as of subject, largely Eastern, James McBey (b. 1883) has certainly attained an important position by the originality and strength of his work. Henry Rushbury (b. 1889), in a style something akin to Sir Muirhead Bone's, is doing fine work in landscape, while Sir George Clausen (b. 1852), E. S. Lums den (b. 1883) and many others have a merited reputation in the same genre. F. L. Griggs (1876-1938) revived the imaginary architectural composition originated by Piranesi, and made of it a delicate and original means of expression. In portraiture, Fran cis Dodd (b. 1874), Gerald Brockhurst (b. 1890) and Malcolm Osborne (b. 188o) have done admirable work.

In Holland, as might well be expected, much work of impor tance was done in the second half of the 19th century. J. B. Jongkind (1819-91), Josef Israels (1824-1911) and Mathijs Maris 0839-1917), though the work of the latter is the oc casional essay of a painter, are artists of the first rank, while C. Storm van's Gravesande (1841-1924) and Marius Bauer (1867 1932), have contributed something considerable to etching. Scandi navia has produced one etcher of astonishing virtuosity in the person of Anders Zorn (186o-192o), and in Germany and Austria, while no artist of the very first rank has, so far as one can judge, appeared, much etching of real distinction has been and is still being done.

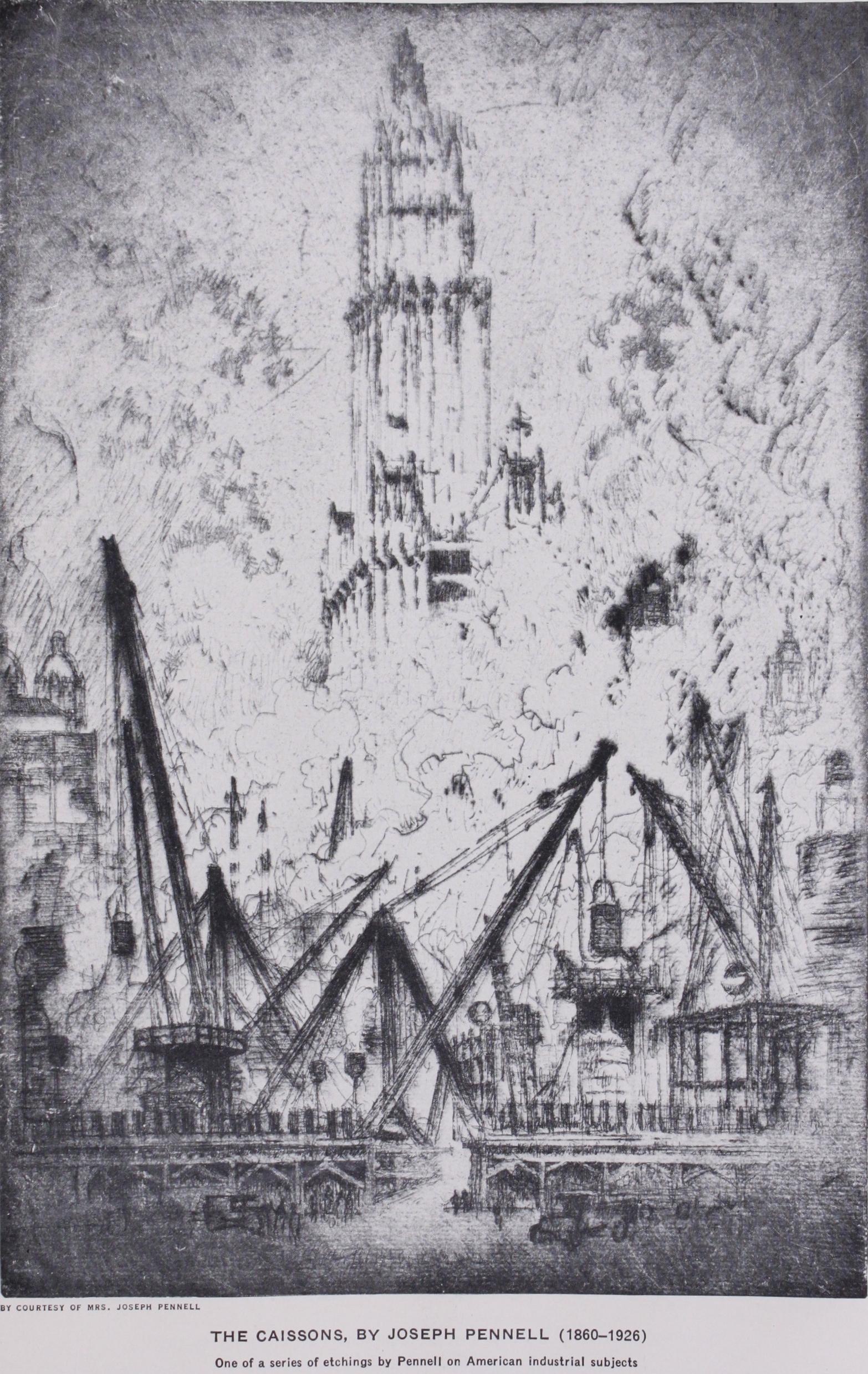

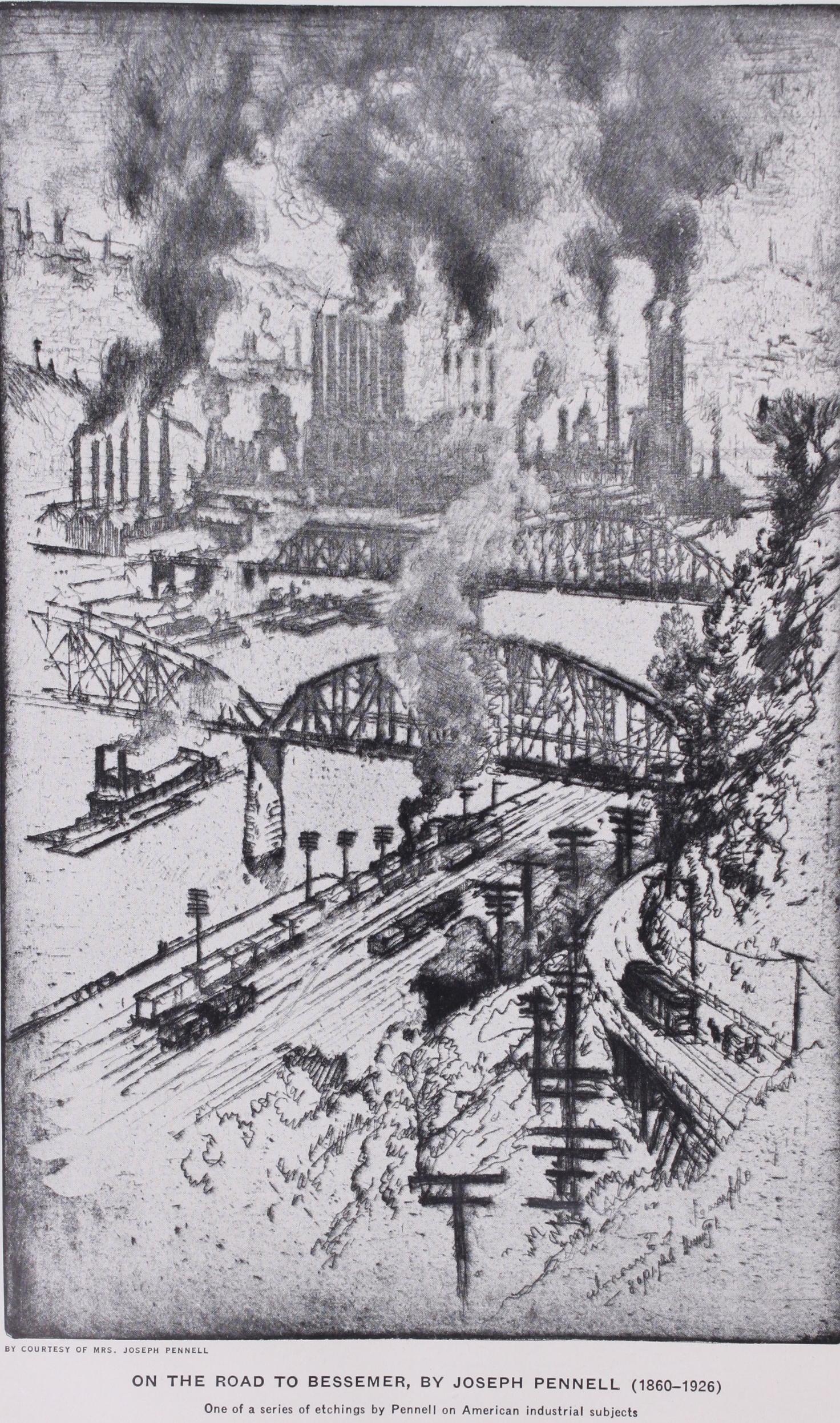

Since Whistler the interest in etching in America has been very intense and a great deal of work has been done, largely, it is true, by artists working abroad, of whom Joseph Pennell (186o-1926), D. S. Maclaughlan (1876-1938) (a Canadian by birth), Frank W. Benson, Herman A. Webster and Arthur W. Heintzelman are perhaps the most notable. (See also LINE ENGRAVING; DRY