Exhibition Architecture

EXHIBITION ARCHITECTURE. An exhibition or ex position is an organized display of works of industry, science, and " art, usually international in range of selection and appeal. Market, fair, mart, exhibition and exposition are terms used almost inter changeably. A fair is often a special market ; and a mart has been defined as a greater species of fair. An exhibition is any general and public display, and in particular a public show of goods for the promotion of trade. Generally, an exhibition or exposition is assumed to reflect human progress, to be open to every branch of human effort and to have a didactic import. A fair may be as sumed to assemble raw and manufactured articles for brief dis play and to be commercial.

Design.—Some of the later "sample" fairs have made use of temporary and flimsy structures, like booths in a market place. The larger of such fairs, however, have inclined to use great permanent buildings, however scattered. Special expositions, fol lowing the example set by London with the Crystal Palace, have erected on such open spaces as were available huge structures, at least one of which is usually permanent.

In Chicago, 1893, the World's Columbian Exposition gave breadth, freedom and largeness of scale to all future planning and designing of World's Fairs. Its conception was that of Daniel H. Burnham, architect of Chicago, and the Architectural Com mission consisting of : Richard M. Hunt, George B. Post, McKim, Meade & White, all of New York; Peabody & Stearns, Boston; Van Brunt & Howe, Kansas City; and five Chicago firms: Burling & Whitehouse; Jenney & Mundie; Henry Ives Cobb; Solon S. Beman; Adler & Sullivan, with Charles Atwood as Chief of De sign. These men worked on 600 ac. of undeveloped park land as on a blank piece of paper. They conceived an entire investiture for the exposition—landscape, buildings and sculpture—and had the satisfaction of seeing their broad conception grow into a real ity. The Buffalo Pan-American Exposition, 1901, expressed itself in the free classical style as developed at Chicago in 1893, but the development in electricity added new effects in illumination. The Universal Exposition in St. Louis, 1904, employed the largest area so far given to such a plan, about 800 acres. The programme of obtaining an open space and planning for it a series of entirely new buildings in a setting of lagoons, drives, gardens, fountains and sculpture, all to combine in a single, new, comprehensive art ex pression, was generally adopted. The design was in the hands of the following architects: Carrere & Hastings; Cass Gilbert of New York; Walker & Kimball, Boston; Van Brunt & Howe, Kansas City; Widman, Walsh & Boisselier; Theodore Link; Barnett, Heynes & Barnett; Eames & Young; Isaac S. Taylor, all of St. Louis. E. L. Masqueray was Chief of Design.

By the time the Panama Pacific International Exposition at San Francisco, 1915, was planned, the designing of exposition buildings and grounds had become almost a profession. One of Burnham's later associates, Edward H. Bennett, was employed as architect of the grounds, and he produced a novel plan—a series of courts which met the climatic need of trapping the sun light and sheltering the visitors from the brisk breezes that blow across San Francisco bay in midsummer. This led to an archi tectural treatment of the structures by courts, so that each de signer in reality did the sides of four buildings, while other de signers did the outer walls of the same buildings. The second respect in which the designing for San Francisco was unusual was that Jules Guerin was chosen as head of the department of colour, and while working in co-operation with the architects he went somewhat independently to work planning for a freer use of colour than in any other group of modern times. Several schools of architecture were represented in the designing of the courts Moorish-Spanish, Romanesque, Italian Renaissance; and it is re markable that with the extensive use of pink, tan, orange, red, yellow and green, the effect of the whole was harmonious and rich. The Architectural Commission was: Thomas Hastings; Henry Bacon; McKim, Meade & White, of New York; Robert Farqu har, Los Angeles; George W. Kelham; Louis C. Mulgardt ; Arthur Brown Jr., San Francisco; with executive Council of three archi tects: Willis Polk, Clarence R. Ward and William B. Faville, all of San Francisco. San Diego in the same year employed only one architect, Bertram G. Goodhue, and he adapted the more ornate architecture of Spain to the needs of modern life.

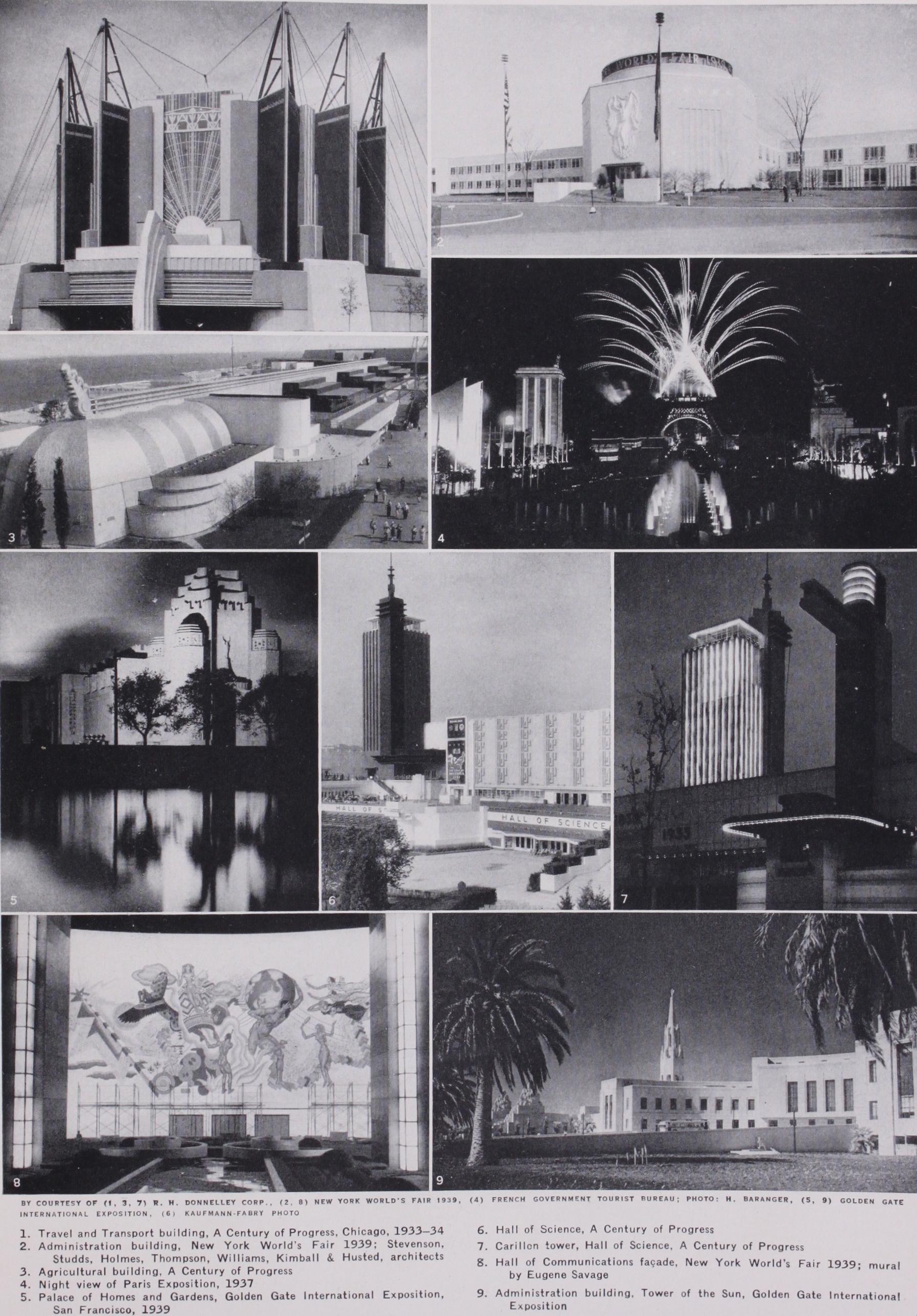

The architecture of A Century of Progress Expositions, Chi cago, 1933-34, was an expression of the trend to cast adrift from the past, following no pattern or groove of former expositions. It depended for its character and effectiveness on simple planes and colour—the results of architectural requirements—rather than an exuberance of plaster ornament and decoration. There was an effort towards simplicity in design and towards an honest func tioning of the buildings. The architecture took into account its primary function, that of housing an exposition;—considered the movement of great masses of people into and through the grounds and buildings with comfort and safety, and also provided for at tractive and suitable settings for exhibits that reflected the scien tific and industrial progress of the past century.

The economics of the day was also a determining factor in the architecture, requiring maximum use of prefabricated and simple materials. Practical reasons dictated many of the innovations. The use of windowless buildings was the result of required econ omy and of the scientific fact that artificial illumination provided constant and uniform control of light on the exhibits.

The architecture of A Century of Progress was in the hands of a Commission consisting of Raymond Hood, Harvey Wiley Cor bett, Ralph Walker, New York; Paul Phillippe Cret, Philadelphia; Arthur Brown, Jr., San Francisco; John A. Holabird, Hubert Burnham, Edward H. Bennett, Chicago. Daniel H. Burnham, Jr. was Director of Works, Louis Skidmore, Chief of Design, Joseph Urban, deceased, colour 1933, and Shepard Vogelgesang, colour One of the outstanding features of the '33 and '34 expositions was colour. Brilliant reds, yellows, greens and blues were used in their pure form for the first time in the exterior treatment of a large architectural composition. The simple surfaces of the build ings and the fact that the Exposition was silhouetted against a grey city were some of the determining factors in the brilliant colour scheme.

San Diego held its second exposition in 1935 and is repeating in 1936. The beautiful buildings and grounds of its 1915 Exposi tion have been reconditioned and maintained with the exception of a few large new buildings erected by industrial firms. These do not follow the Spanish tradition but are of modern simplicity, which when combined with the luxuriousness of the grounds and the richness of the Spanish, form a harmonious building ensemble.

For the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley the majority of the buildings were erected of concrete on the most simple of classic lines. Variety and colour were introduced into the composition by the kiosks, band-stands and pavilions. Rio de Janeiro in 1922 and Seville and Barcelona for 1928 and 1929 adopted comprehensive plans. All designing and displays for the Paris Exposition des Arts Decoratifs of 1925 were required "to present the character of art and to be of strictly modern tendency." Nothing was to be exhibited which to the authori ties would seem to be an expression or an imitation of any ancient style. The effect was to bring to one centre illustrations of the increasing radicalism that has marked recent design through out continental Europe. Frankly temporary, the new constructions and the treatments of the gardens and plazas offered the appeal of lightness, brilliance and the bizarre.

In 1931 the French again broke from traditional type of expo sitional architecture in their Exposition Coloniale Internationale in the Bois de Vincennes. This site regulated the design which re sulted in an arrangement of unsymmetrical planning of courts and vistas to fit in the existing woods. The style of architecture was determined by the particular type indigenous to the French Colo nies and Colonies of other participating governments. The effect was unique and pleasingly blended together due to the planting.

Influence.

Fairs and expositions of all sorts must be assumed to exercise an influence that is immediate, continuous, far-reaching. Two years sufficed to carry to all the centres of the Occident the influence of the Exposition des Arts Decoratifs of 1925. Its diagonal lines, its "philosophical" and original motifs, its inde pendence of tradition, its studied avoidance of natural and pic torial forms, were soon reflected in design.To the San Diego exposition and the ascendancy of Goodhue in the United States is attributed the striking spread of Moorish Spanish architecture throughout the southern States of the Amer ican Union.

Probably the most impressive evidence of the influence of such an exposition is provided by the exposition in Chicago in 1893. The magnificence of the court of honour, the manifest harmony suggested by a uniform cornice line, the dignity and grace of the classic orders, came to the people of the United States and Canada as something akin to a revelation. The public buildings erected in the United States from 1893 to 1915 were, with few exceptions, built on the more usual classic lines ; however, it is interesting to note that Louis Sullivan, Architect for the Transportation Build ing, presented to the public an individual and new expression in design and to many he became the founder of modern architec ture.

The following influences from A Century of Progress are being felt : a colour consciousness, simplicity and cleanness of line in ar chitecture, and the use of architectural treatment and colour as an integral part of exhibits and displays. These are recognized as having an advertising and merchandising value in the design of shop fronts, interiors and in the industrial field. (L. SK.)