Experimental Embryology

EXPERIMENTAL EMBRYOLOGY. The study of gen eral or comparative embryology reveals the fact that during their normal development, animals pass through a number of visibly different stages; each stage being characterized by the possession of various structures in a condition more or less well formed, as compared with earlier and later stages. In other words, the devel opment of an animal can be unravelled into a series of sequences of structural patterns. Once the fact of these structural patterns has been established, it becomes interesting to enquire into the reasons why certain stages are preceded and followed by certain others ; why the various organs of the body appear when and as they do ; and whether the stages which follow one another in time, also follow one another as the effect does the cause.

Many such questions can be answered by applying directly to the animal, and artificially altering the conditions at the preceding stage. The process of interfering with the normal development is an experiment, and for this reason the study of the causal re lationships between the various stages of development is called experimental embryology. The experiments themselves may con sist of the removal or addition of definite parts of the embryo, or its subjection to abnormal conditions of temperature, electric currents, or chemical reagents, to give only a few examples. The experimental methods depend of course on the material which is being studied and the question which is being attacked. It must suffice to say, that in all cases, the results of an experimental oper ation must be interpreted in the light of a control experiment car ried out alongside, and under normal conditions.

Development is usually held to start from the stimulation of the egg by Fertilization, or Parthenogenesis. Both these phe nomena have yielded interesting results to experimentation. After stimulation of the egg, the development of the embryo consists of three main processes : cell-division, growth and differentiation.

Cell-division.

The starting-point of sexual and partheno genetic development, the egg, is a single cell; whereas the adult animal to which it will give rise (excluding the Protozoa) contains countless cells. It is obvious that cell-multiplication must take place during development, and its importance is increased by the fact that it has a bearing on the other two processes, growth and differentiation. The volume of a cell cannot be increased above a certain limit without upsetting the convenient ratio of surface to volume. This means that when growth takes place and new living tissue is formed, the existing cells must multiply in order to ac commodate the new material. At the same time, if cells are too highly differentiated (see below), they will be unable to divide. This is especially true of the cells of the nervous system of verte brates; after a stage reached quite soon in man, the cells of his brain and spinal cord never divide again. According to Gurwitsch cell-division is a response to stimulation by ether waves of a length of between 1,900 and 2,000 Angstrom units. Apart from this theory, it must be confessed that very little is known as to the causes which result in the splitting of the cell-nucleus into two, and the subsequent division of the whole cell itself. For further information the reader is referred to the section on Parthenogen esis (artificial), for the active stimulus in causing an egg to start developing appears to be that which causes it to divide.

Growth.

Growth is increase in bulk. In an animal it may be caused by accumulation of non-living substances, as when an egg cell is filled with yolk, or when the whole organism absorbs water. "True" growth, however, is the production of new living material, new protoplasm. This is one of the fundamental properties of life, which is constantly concerned in assimilating foreign matter and building it up into protoplasm. At the same time, protoplasm is always being broken down with wear and tear; but when the proc ess of building-up (anabolism) is more active than that of break ing-down (katabolism) the result is growth.It has been found that apart from the ordinary food-substances, others are necessary for growth. Chief among these are the vita mins, about which little is known, except that the effect which they produce appears to bear little relation to the quantity of them present. This would indicate that they act not as raw building materials, but as ferments and catalysers accelerating the processes of building. Other substances are known whose property it is to accelerate the growth of tissues; these were discovered by means of experiments of growing pieces of tissue under aseptic condi tions in small glass vessels, a technique which is called "tissue culture," or growth "in vitro." One of these substances, obtained from young embryos and hence called embryo-extract, encourages growth in vitro, which without it, would not take place. Another such substance is obtained by killing some cells and maintaining them at the normal temperature of the body, when they undergo a disintegrative process known as autolysis and furnish a sub stance (autolysed extract) which is a very powerful promoter of growth. The interest of this substance is increased by the fact that its effects are similar to those produced by extracts of malig nant tumours (cancers) .

For further details the reader is referred to the section on Growth, but before leaving the subject it must be mentioned that if growth takes place at unequal rates in the various parts of an embryo, the result will be an alteration of its shape ; or in other words, its various parts which may previously have been similar, come to be different. This process is known as morphological (form-) differentiation. The importance of such changes of shape become obvious when it is realized that for example the fertilized egg of a man is spherical.

Differentiation.

The definition of morphological differentia tion, or change of shape, has just been given. The earliest exam ple of this in the development of most animals is the conversion of the solid egg-cell into a hollow ball composed of many smaller cells : the blastula. Later, this hollow ball is converted into a double-layered sac or gastrula, in which the original cavity of the ball (the blastocoel) is obliterated and its place taken by the cavity contained by the innermost of the two layers of the sac (the enteron, or future alimentary canal). Then, the sac elongates and the general shape of the future animal is roughed out. If the animal is a newt, the rudiments of the limbs and of the tail arise as little cones in which growth takes place more rapidly than in the neighbouring regions. All these cases are examples of mor phological differentiation.It is now necessary to turn to the cells of which the embryo is composed. These cells have been derived by repeated cell-division from the egg-cell, and as up to this stage there has been little or no increase in the total amount of living matter; the cells are thus much smaller than the original egg. If the egg contained yolk, then some of the cells produced from it will contain yolk, and others not, but otherwise, there is no visible difference (save, usu ally, size) between these cells. Later on, however, an actual differ ence between the cells becomes visible. Some become muscular cells, others nervous, others again form part of epithelia which line the cavities and surfaces of the embryo. Sheets of cells which have been modified in the same way form a tissue, and the process of modification which these cells have undergone, rendering them different from any other cells, is called histological (tissue-) differ entiation. Undifferentiated cells, such as are found in the earliest stages of developing embryos, are called embryonic ; and it is found that whereas embryonic cells are capable of rapid cell-di vision and growth, differentiated cells are less easily capable of cell-division and therefore of growth. This is the connection be tween cell-division and differentiation referred to above; the reason for it must be that a differentiated cell no longer consists of pure protoplasm like an embryonic cell, but is encumbered with other inert substances which confer upon it its differentiation and hinder its division. The experimental evidence for this is obtained from tissue-cultures, in which it is found as a rule that the rate at which tissues grow is greater if they lose their differentiation (undergo dedifferentiation). Conversely, cells which divide too rapidly will not redifferentiate.

Cleavage.

The process of repeated cell-division whereby the egg-cell fractionated into a number of smaller cells or blasto meres, is known as segmentation or cleavage. Whether the first cleavage separates the future right and left halves, or the future front and rear halves, or diagonal halves of the embryo, it is obvious that the first cleavage (and subsequent cleavages also) separate from one another parts of the embryo which have very different prospective fates in normal development. It therefore becomes important to enquire whether the origin of differentia tion may be due to inequalities of cell-division during cleavage. In such a matter it is necessary to consider the division of the nucleus and the division of the body of the cell or cytoplasm.

Nuclear Division.

Experiments have proved that it is not in divisions of the nuclei during cleavage that differentiation origi nates. For by making eggs (of the frog, of the worm Nereis, or of the sea-urchin) undergo cleavage compressed between plates of glass, or by shaking them, the normal arrangement of the blasto meres is completely upset. After release from the glass plates, the embryos round themselves off again, and a given blastomere contains a nucleus which, in normal circumstances, would be situ ated in a different blastomere. Nevertheless, subsequent develop ment of embryos operated upon in this way is normal. This can only mean that all the nuclei are equivalent, that their division has been strictly equal, and that they are not responsible for the origin of differentiation. The most elegant demonstration of this was obtained by tying a loop of fine hair round a fertilized but still undivided newt's egg, and constricting it almost into two, in the form of a dumb-bell. By this process, the nucleus was re stricted to one side, in which it underwent division, while the other side had no nucleus at ail. When the nucleated side contained six teen nuclei, the hair-constriction was released slightly, and one nucleus was able to pass across the narrow bridge into the previ ously enucleate half. When the nucleus had passed, the hair was pulled tight and completely separated the two sides from one an other. Both sides could develop normally into diminutive em bryos, and as the nucleus which passed across could hardly be the same one in any two experiments, the experiment proves that all the sixteen nuclei were equivalent, and capable by themselves of ensuring normal development.The experimental results just described are of fundamental im portance, for they definitely disprove the celebrated Roux-Weis mann theory of development. This theory attempted to attribute the origin of differentiation to unequal nuclear division during cleavage.

Cytoplasmic Division.

Turning now to the consideration of the nature of the division of the cytoplasm between the blasto meres during cleavage, the results obtained from experiments on different kinds of animals are apparently (but only apparently) contradictory. The method adopted is to separate the blastomeres from one another at the 2-cell, 4-cell or subsequent stages of cleavage.In the sea-urchins, it is `found that a single isolated blastomere from the 2-cell or the 4-cell stage is capable of developing into a perfect little larva, of half or quarter normal size respectively. These blastomeres which would normally have produced only one half or one-quarter of the larva, are thus shown to be capable of regulating and giving rise to a whole. Eggs which divide into blastomeres capable of such regulation are called "regulation eggs," and their blastomeres are called totipotent.

At the other end of the scale are eggs like those of the Ascidians (Sea-squirts) and Ctenophores (Comb-jellies or Sea-gooseberries), in which isolated blastomeres will only give rise to that which they would have ordinarily produced in normal development. Here, the blastomeres are differentiated and "set," like the separate pieces which make up the pattern of a mosaic. Such animals are consequently said to have "mosaic-eggs." The difference between regulation-eggs and mosaic-eggs is really only due to a matter of time. In the regulation-eggs, the equivalence of the cytoplasm persists longer than in the mosaic eggs, and in time, even in the sea-urchin, the different regions lose their totipotence. The mosaic-eggs, on the other hand, have por tions of their cytoplasm determined for various fates already in the egg, before fertilization, and even when it is still in the ovary of its mother.

Experiments on cleavage therefore show that it is in determina tions (as yet invisible) of the cytoplasm, or in the specialization of "organ-forming substances," that the first manifestations of differentiation are to be found. The next problem is to find out the cause for the determination and localization of these regions of the cytoplasm.

Polarity and Symmetry.

The eggs of frogs and newts oc cupy a peculiar position as regards the power of regulation, and therefore the degree of determination of the cytoplasm of their blastomeres. In the first place it must be realized that these eggs contain a fair amount of yolk which is accumulated in one (the lower, or so-called vegetative) hemisphere. The upper (or so called animal) hemisphere contains little yolk. The distinction between the animal and vegetative hemispheres enables the com parison to be made between the frog or newt's egg and the globe, with its north and south poles. In other words, the egg has an axis and polarity, and the upper (or animal) pole of the egg will become the head of the future embryo, while the lower (or vege tative) pole will become the tail. The axis of the egg appears to be determined while it is still in the ovary by the orientation of the little arteries and veins ; the animal pole is the region where the blood is brought to the egg-cell, and where the rate of protoplasmic activities is higher than elsewhere. This rate dimin ishes away from the animal pole and towards the vegetative hemisphere, so that the axis of the egg coincides with an axial gradient (q.v.). From experiments on the eggs of sea-urchins it is known that if the axial gradient of rate of activities of the protoplasm is abolished (i.e., the rate 'of activities is made uni form), the embryo has no polarity. It is therefore legitimate to conclude that the localization of the site of the future head in the egg of a frog or newt, is due to that site being the highest point on an axial gradient, and that the axial gradient itself is deter mined by the greater stimulation which that site received as a re sult of the orientation of the blood-vessels in the ovary.Thus far, the egg has a future head-end and tail-end, but it re mains to determine which side shall be right, which left, and accordingly which dorsal and ventral. This determination is that of a plane of bilateral symmetry, which of course passes through the egg-axis. The plane of bilateral symmetry is as a rule fixed by the point of entry of the sperm fertilizing the egg, and in such a way that the mid-dorsal line of the embryo is the meridian ex actly opposite that on which the sperm entered. The mid-dorsal line is taken as the most important, because it is on this meridian that the process of conversion of the blastula into the gastrula be gins, by the overgrowth of the so-called dorsal lip of the blasto pore. It will be shown below that the region of the dorsal lip of the blastopore is essential for the formation of the embryo. Its in terest from the present point of view is the fact that an isolated blastomere of the 2-cell stage will develop normally into a perfect embryo if it contains a part of this region, but not if it lacks it. This region is therefore a cytoplasmic determination, or origin of differentiation (visible in the frog as the so-called grey crescent), and which is itself due to the point of entry of the sperm. This fact is proved by causing sperm to enter an egg on a selected meridian and observing its subsequent relation to the plane of bilateral symmetry; and also by the experiment of causing two sperms to enter the same egg simultaneously, when it is found that the site of the dorsal lip of the blastopore lies on the meridian opposite that which bisects the angle subtended at the centre of the egg by the points of entry of the two sperms. This conclusion, arrived at with frogs, must, however, not be over-generalized, for it does not apply to sea-urchins. It is important to notice that polarity and bilateral symmetry, which are the prime differentia tions in the egg of frogs and newts are induced by stimuli which act on the egg from outside. This means that the origin of differ entiation is to be found in the reactions of the cytoplasm to external stimulation at a definite site. The origin of differentia tion also coincides with the formation of an axial gradient of rate of protoplasmic activities, and the importance of this is that the qualitative nature of the tissue differentiated at any point is in the first place determined by the relative quantitative rate of protoplasmic activities at that point. In other words, the pro spective fate of a cell in normal development is determined by its position relatively to the axial gradients. This principle will now be further illustrated.

Axial Gradients and Differentiation.

When a piece is cut out of the body of a Planarian worm, the anterior cut end of the piece may regenerate a head, or a tail. That it should be capable of doing either is due to the fact that the nuclei all over the body are equivalent, and that the cells of such a lowly animal as Pla naria are easily capable of reverting to an embryonic undiffer entiated condition. Actually which structure will be formed de pends on how much higher the rate of protoplasmic activities is in the cells of the anterior cut surface than in the rest of the piece. If the rate at the anterior cut surface is relatively sufficiently high, a head will form, and the degree of perfection of this head varies with the height of the rate. If the rate is too low, no head will be formed. The relative rates of protoplasmic activities can be controlled by means of certain substances (which have selective effects in increasing or depressing the activities of regions of high or low rate), and there is therefore experimental evidence that the quality of the tissue differentiated is determined by the rela tive quantitative rate of protoplasmic activities at the place in question. So it may be imagined that in the development of the egg, the axial gradients evoke qualitative differential responses from the cells according to the level of quantitative activity at which they are situated. Further examples will be given of the action of gradients in determining differentiation, but attention must now be turned to the nature of differentiation.

Plasticity and Determination.

Without being totipotent like the blastomeres of the 4-cell stage of the sea-urchin, cells may still show plasticity, in the sense that they are capable of differen tiating into tissues other than those to which they would normally give rise. In the double-layered sac or gastrula, the outer layer is the ectoderm which will produce the epidermis and nervous system while the inner layer or endoderm will furnish the alimentary canal and its derivatives, like liver, lungs, etc. If a cap of cells be cut off from the animal hemisphere of the blastula of a sea urchin, the remainder of the blastula cuts its loss and forms a gastrula smaller than normal (owing to the loss of tissue) ; and its inner layer or endoderm is reduced in size proportionately. This means that some of the cells which would normally have come to form part of the endoderm, actually become ectoderm; for the endoderm is in these animals formed by an inpushing from the surface of the blastula, and the proportionate reduction in size of the endoderm implies that fewer cells than normal are pushed in. That these cells should be capable of turning into ectoderm instead of into endoderm means that at the time when the opera tion was performed, they were not irrevocably determined. Identical results are obtained in newts up to an early stage of gastrulation, by experiments of transplanting pieces which would normally have become ectoderm, for instance ("presumptive" ectoderm), into other regions (see GRAFTING IN ANIMALS).By transplanting between two different species of newts (hetero plastic transplantation), the cells of which differ as to their pig mentation, and in other respects, it is possible to identify the pieces of grafted tissue long after the operation, and to make certain of their actual fate. So, at this early stage in newts, a piece whose presumptive fate was ordinary epidermis, when trans planted to the appropriate region, actually became part of the brain and eye; and a piece of presumptive brain could be made to become part of the gills.

After a certain stage, however, these exchanges can no longer be made. If a cap of cells be cut off from the animal hemisphere of a gastrula of the sea-urchin, the endoderm remains of its normal size and is therefore out of proportion to the reduced ectoderm. The endoderm is therefore determined at this stage, and can no longer be converted into ectoderm. At the same time, within the endoderm itself determination has not yet taken place. The endo derm normally becomes divided into a number of regions bearing a certain proportion to one another. If at this gastrula stage when the endoderm cannot be turned into ectoderm, a piece of the en doderm be removed, the remainder will parcel itself out into the normal number of subdivisions in correct relative but reduced pro portions. This illustrates the important fact that during develop ment, determination takes place progressively.

Similarly in the newt, at a late stage of gastrulation, presumptive material shows when transplanted that it is determined. Pre sumptive eye material will differentiate into an eye even in ab normal positions such as the abdominal wall, facing inwards. Tissue which is "fixed" in this way is called self-differentiating. In the sea-urchin larva the mouth is self-differentiating, for it forms regardless of whether the alimentary canal is normally pushed-in or is experimentally everted (as in the so-called "exo gastrula") . On the other hand, tissue which requires to be acted upon by neighbouring tissue in order to differentiate, is called de pendent-differentiating.

Interesting examples of the effects which certain tissues exert upon certain others, can be obtained from tissue-culture experi ments. Epithelium by itself, or connective tissue by itself, when grown in vitro, tends to lose its differentiation, and its cells revert to an embryonic condition. If, however, these tissues are cultured together, they maintain their differentiation ; and if one of the two tissues dies, the other loses its differentiation. Use has been made of this property of inducing dependent differentiation in order to cause certain tissues to differentiate at will. Cultures of kidney-tissue of a mouse, or of a carcinomatous tumour of the mammary gland, grow as sheets of undifferentiated tissue in vitro. If some connective tissue is added to the cultures, the kidney tissue redifferentiates its tubules, and the tumour gives rise to structures, resembling those of a normal mammary gland. It is possible, therefore, that the contributory causes in tumour-forma tion may include not only an excessive amount of a growth-pro moting substance (such as the autolysed extract mentioned above) but also the removal of the restraining influence on the part of other tissues, which normally produce and maintain a dependent differentiated condition in the tissue which has become tumorous. Further examples of dependent differentiation will be mentioned below.

Chemo-differentiation.

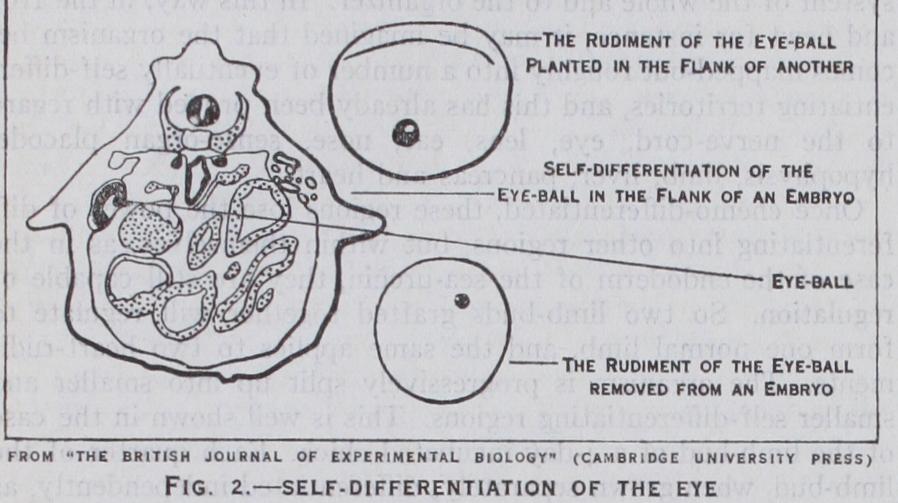

In the newt and in the frog, the brain and spinal cord arise as a groove along the back, between a pair of so-called neural folds. The folds eventually meet over the groove, which thus becomes converted into a tube sunk beneath the surface. From the front end of this tube which is enlarged to form the brain, the eye-balls are pushed out to each side. If at an early stage, when the brain is still an open groove, a rectangular piece is cut out from it, rotated through I 80°, and replaced, it continues its development by self-differentiation. In such a case, the anterior cut of the rectangular piece might pass through the eye-rudiments, and after rotation, portions of these eye-rudiments would find themselves transported back to abnormal regions. It is a fact that such operated embryos when they develop have not two eyes, but four, one pair behind the other, and of such a size that the sum of the sizes of all four is equal to the joint size of two normal eyes. This shows that the presumptive eye-rudiments were, although invisibly, yet nevertheless qualitatively and quan titatively, determined at the stage operated upon. A fixation of presumptive fate in this manner must be based on the presence of a definite amount of a chemical substance in the area which is determined. For this reason, determination of future organs may be called chemo-differentiation. The experiment just described is further interesting for two reasons. It shows by the variation of the constitution of the four eyes which are formed (which do not all possess the correct proportion between the sizes of the stalk, sensory layer and pigment layer), that not only is the eye deter mined as a whole, but that its constituent portions are also sever ally determined. The other point is that although the amount of determined tissue in any one of these four eyes is less than in a normal eye, nevertheless, it rounds itself off after the manner typical of an eye-ball. The same result can be obtained from other organs such as the nerve-cord itself, and it shows that the process of shaping the organ (or morphological differentiation) is distinct from the process of specialization of its constituent cells (or histological differentiation). The former is concerned with conditions of available space and material and is the property of all the cells of the organ in general. The latter is the specific effect of chemo-differentiation on certain cells.

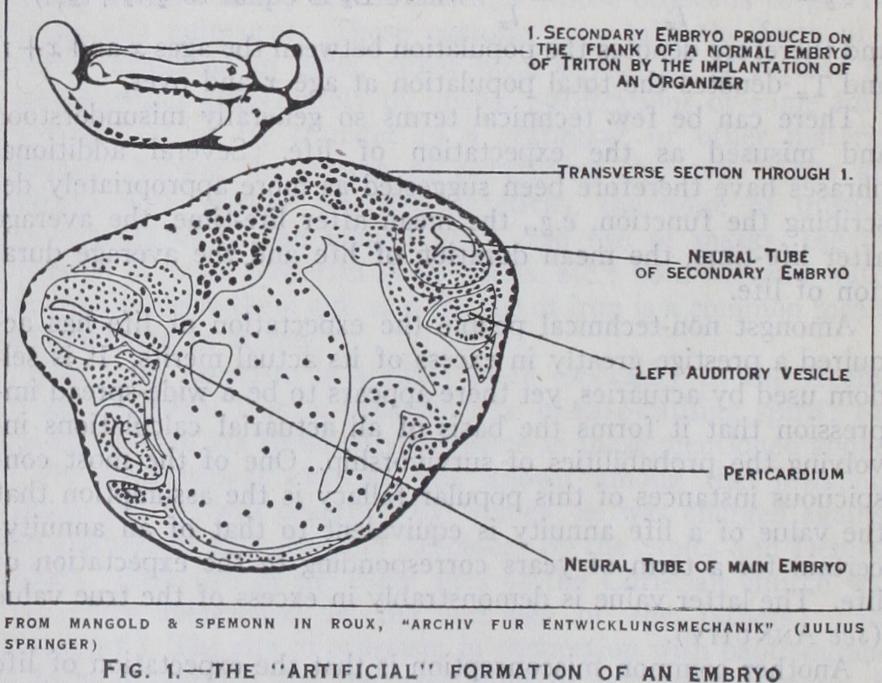

Organizers.

One region of the embryos of newts and frogs is peculiar, and that is the region of the dorsal lip of the blasto pore. The tissue in this region becomes tucked-in beneath the superficial layer, and grows forwards beneath it, forming the roof of the enteron, or cavity of the gastrula. If a portion of this re gion be grafted into another position, it does not follow the differ entiation of its surroundings nor does it simply pursue its normal prospective fate by self-differentiation, but it actually induces the cells which surround it, wherever it happens to be, to differen tiate into the essential structures of an embryo. These structures are the nerve-cord, notochord, plates of muscle, kidney-tubes, eyes and ears. Since these structures lie along the axis of the body they are called the axial structures. The dorsal lip of the blastopore, therefore, has the power of organizing an embryo, for which reason it is called an organizer.The organizer is that region which arises opposite the point of entry of the sperm, which is visibly differentiated as the grey crescent in the frog, and which an isolated blastomere must pos sess if it is to develop. The organizer is therefore an origin, and originator of differentiation, itself due to an external stimulus. With regard to its method of action, it is non-specific, for not only can organizers induce the formation of embryos in tissue of a dif ferent species, but even of a different order, as when the organizer of a toad works on tissue of a newt. Further, the quality of the tissue "organized" depends on the place from which the organ izer was taken, and the level on the axial gradient of the other embryo (or "host") at which it is grafted. As new tissue is con stantly turning over the edge of the dorsal lip of the blastopore and growing forwards, a piece of the organizer-region removed at an early stage of gastrulation would normally come to lie in the head, whereas pieces removed at later stages would lie in the trunk. A piece of head-organizer grafted into a host near the ani mal pole will organize a head, while a piece of trunk-organizer grafted into the host at a greater distance from the animal pole will organize a trunk.

Lastly, it is known that the property of organizing is not inher ent in the cells of the organizer, but is something common to the region which they occupy. For if a piece of indifferent presump tive epidermis is grafted into the region of the organizer, and then cut out and grafted into a host, it will be found to function as an organizer. In other words, during its sojourn in the organizer region, it has been infected with the capacity to organize. The Eye and the Lens.—The eye-balls are, as already de scribed, pushed out from the brain and subsequently become con verted into the eye-cups. The lens fits into the rim of the cup, but it arises from a separate rudiment altogether, viz., the super ficial epidermis. How, then, does it come about that the lens dif ferentiates at the correct place so as to collaborate with the eye cup in the formation of the perfect eye ? This developmental cor relation is of the greatest interest and importance. In the first place it was found that in the grass-frog (Rana fusca), the lens did not differentiate if the eye-cup was removed, and that any epi dermis grafted over the eye-cup could be induced to differentiate into a lens, whether that was its presumptive fate or not. In other words, in R. fusca, the differentiation of the lens is dependent on that of the eye-cup which itself is dependent on the organizer. With regard to the lens, therefore, the eye-cup is a secondary or ganizer. The problem is however complicated by the fact that in the edible frog (Rana esculenta) the lens develops by self-differ entiation when the eye-cup is removed (at the tail-bud stage), and not all esculenta epidermis can be induced to differentiate into a lens when grafted over the eye-cup. At the same time, the eye-cup has the power to organize a lens from suitable tissue, as is shown by the fact that it can do so from the epidermis of toads. Rana esculenta, therefore, has a self-differentiating lens, and at the same time its eye-cup is capable of organizing one ; there is therefore what appears to be a "double assurance" that a lens will be formed. On the other hand, Rana fusca has a dependent-differen tiating lens. The apparent contrast between the two methods of lens-formation in such closely related species is, here again, only a matter of time. The self-differentiating capacity of the lens of Rana esculenta only means that at the stage operated upon, the presumptive lens-rudiment had already been sufficiently chemo differentiated to continue its development independently. At the operated stage, this condition had not yet been reached in the case of the lens-rudiment of Rana fusca. In almost all cases which have been sufficiently analysed, an organ which is self-differentiating at a particular stage is dependent-differentiating at an earlier stage. In the final analysis the chemo-differentiation of the various rudi ments is referable to their position with regard to the gradient system of the whole and to the organizer. In this way, in the frog and newt for instance, it may be imagined that the organism be comes mapped-out roughly into a number of eventually self -differ entiating territories, and this has already been proved with regard to the nerve-cord, eye, lens, ear, nose, sense-organ placode, hypophysis, limb, liver, pancreas and heart.

Once chemo-differentiated, these regions lose the power of dif ferentiating into other regions, but within themselves, as in the case of the endoderm of the sea-urchin, they are still capable of regulation. So two limb-buds grafted together will regulate to form one normal limb, and the same applies to two heart-rudi ments. The organism is progressively split up into smaller and smaller self-differentiating regions. This is well shown in the case of the limb-bud of a 4-day incubated chick. Each quarter of the limb-bud, when grown separately, differentiated independently, as a piece of a mosaic, to its presumptive fate.

The Periods of Development.

So far, in this account, it has been shown that differentiation originates in relation to axial gradients and organizers, until the organism is a collection of self differentiating rudiments, developing without regard to one an other and without co-ordination or correlation. It is important to notice that during this period, the organs and tissues differentiate without functioning, as is indeed obvious, for functions cannot be performed until a certain degree of differentiation has taken place. Nevertheless, this distinction is important, for in subsequent stages of development the further differentiation of the organs is conditioned by their functioning. The two periods may accord ingly be called the non-functional and the functional periods of development respectively, and it is to Wilhelm Roux, the founder of modern experimental embryology, that the science is indebted for this distinction. Meanwhile, it must be noticed that during the earlier period of non-functional development, when the self-differ entiating rudiments are pursuing their development independently of one another, regeneration and regulation is not possible. If the limb-bud rudiment is extirpated from a chick embryo during this period, the chick will always lack this limb. This matter has con siderable philosophical interest, for it is common to find that regu lation is regarded as a characteristic and fundamental phenomenon of living matter, and thereby distinguishing the latter from non living matter. That regulation should not be of unfailing occur rence even among living things indicates that caution is necessary before adducing regulation as evidence for the exclusiveness of the nature of living processes. This is further shown by a study of the processes of regeneration, in which it is untrue to say that that which is regenerated is always that which was lost. It may be that too little is regenerated, or too much, or the quality of the regen erate may be entirely different from that of what was lost. Be this as it may, it is nevertheless true that regulation when it does occur is none the less interesting : a matter to which return will be made below. It is now time to turn to the second of Roux's periods of development.

Functional Differentiation.

The blood-vessels of the body are at first laid down roughly in certain definite positions and di rections during the earlier period of non-functional self-differentia tion. Their subsequent differentiation and the details of their con nections with the tissues and one another take place during the later period of functional differentiation, and are governed actu ally by the functions which they perform in supplying the various tissues with blood according to their needs. The diameter of the vessels and the shaping of their bifurcations become adapted to the flow of blood so as to oppose the least resistance to it. The walls of the vessels differentiate in accordance with the internal pressure of the blood which they have to withstand. So when a section of vein (which normally only has to deal with low pressures, and has a relatively feeble muscular wall) is transplanted into a position in the course of an artery (which has to withstand high pressures, and has a well-developed muscular wall), it becomes structurally converted into an artery, and its muscular wall becomes twice as thick. The definitive form of the blood-vessels is therefore the manifestation of their functional activity.Tendons form the link between muscles and the bones to which they are attached. From their position it is obvious that they have to stand great tensions, and the fibres of connective tissue of which they are composed are arranged parallel to one another. The dif ferentiation and parallel arrangement of these fibres is brought about by the pull which the muscle exerts at the end of them. This can be proved by cutting a tendon and allowing it to regener ate. Instead, however, of allowing the muscle to exert its pull on the fibres, the muscle can be cut out and a silk thread can be left in the track of the differentiating fibres. If this silk thread is pulled, the fibres of the tendon become orientated parallel to the line of this artificial tension. It is the function which they sub serve, therefore, which is responsible for the differentiation and perfection of tendons.

The formation of bone presents a case not very dissimilar from that of tendons. Bone is not solid all through, but is composed of a large number of splinters and spicules, and the first appearance of these is a result of self-differentiation without function. The structure of a fully-formed bone, however, shows that the splin ters are so arranged that they are in a position to withstand the maximum amount of pressure and tension to which the bone is normally exposed. It looks as if the differentiation of these splin ters was determined by the incidence of these pressures and ten sions. This must in fact be the case ; for if a bone is broken and reset, the incidence of the pressures and tensions will be slightly altered, and it will be found that the old splinters of bone will be removed and replaced by others which answer more accurately to the functional requirements of the whole bone. To account for this, it is necessary to assume that there is a particular condition of pressure and tension which is most suitable for the differentia tion of bone-splinters. That being so of a number of splinters lying in all directions, those which lie in the lines of pressure and tension will be favoured, while the others will be handicapped in their dif ferentiation. This means that there is an internal struggle between the parts of an organism, some of which are preserved and others eliminated by a particular form of natural selection. The optimum conditions for which such a competition strives may not only be special functional situations, but also conditions of available space and nourishment.

The muscles of the body of a higher animal such as a dog may be of one of three kinds. There is the smooth muscle which forms the wall of the blood-vessels, the alimentary canal, and the blad der, and which is not subjected to any very violent or prolonged exertion. Then there is the musculature of the heart, which pos sesses a particular striated structure, and which is given to a per petual and rhythmical life of contraction. Lastly there is the striped skeletal musculature of the body, which is under the control of the will, and which is capable of very violent effort, as in running up stairs for instance. Now, the function of the musculature of the wall of the bladder (of a dog) may be increased by connecting the bladder (by means of a cannula) with a tube leading from a jar containing a neutral fluid. In this way the amount of fluid in the bladder and the pressure at which it stands can be artificially, and precisely, increased. In this way the wall of the bladder-can be made to expel more than a hundred times the normal amount of fluid per day, and it was found that the musculature took on the function of contracting rhythmically, and as often as two hundred times a minute. At the same time, the muscular wall of the blad der becomes very considerably thickened, and its cells differen tiate into striated muscle-cells, similar to those of heart-muscle. These remarkable results are due to the effect of the function of expelling large quantities of fluid at high pressure. Other cases of functional differentiation are to be found when tadpoles are fed on herbivorous and carnivorous diets. To obtain the same amount of energy from animal and from vegetable food, it is necessary to eat much more of the latter, and consequently the alimentary canals and absorbtive digestive surfaces of herbivorous animals are as a rule larger than those of carnivores. Of the tadpoles treated with the two kinds of diets, it is actually found that the absorbtive area of the vegetarian tadpoles is twice that of their carnivorous brethren.

These cases of functional differentiation grade insensibly into those of the functionally adaptive effects of use and disuse. This can be particularly well illustrated by contrasting the muscular development of athletes and of persons who lead a more sedentary life. The nervous system itself, after a rough outlining of its rudi ments by non-functional differentiation, becomes perfected with the help of function.

The Nervous System.

The functional differentiation of the nervous system is peculiar because of the particular nature of its function. Nerves are composed of fibres which are formed as out growths from the nerve-cells or neurons. Their development can be studied in tissue-cultures, and their formation is a self-differen tiation. Other experiments have shown that the direction of the outgrowth of the fibres can be controlled at will by passing an elec tric current through the tissue culture. Now, one of the manifes tations of the axial gradient is a difference in electric potential passing down the axis of the body. (The head-end is electronega tive in the external circuit relatively to other regions.) It must therefore be due to this electric gradient that the fibres in the brain and spinal cord grow down the cord and give rise to the fibre-tracts. Further, the tissue-culture experiments have shown that if a conductor carrying an electric current is led through the culture, the fibres grow out at right angles to the conductor. Re turning to the nervous system, when a nervous impulse passes down a fibre, it may be compared with a conductor carrying an electric current. If, therefore, impulses pass down the fibres which run down the spinal cord, the neurons which are then differentiat ing will tend to grow their fibres out at right angles from the spinal cord. This is precisely what the motor nerve-roots of the spinal cord do.The question now arises as to why the nerves connect up with their proper terminations. If a limb-bud of a newt is cut out and replaced a certain distance behind its normal site, the nerves which normally supply it grow out, and find the limb-bud in its abnormal position. There must therefore be some kind of chemical attrac tion which guides the nerves to their appropriate destinations. The next problem to consider is why the brain and spinal cord develop special accumulations of nerve-cells exactly where they do, in relation to particular organs, such as the eyes or the limbs. The fibres running into the brain from the eyes end in the roof of the region known as the midbrain, where normally there is an accumulation of other nerve-cells which carry on the impulses else where. If the eye be removed at an early stage, however, this accumulation of nerve-cells in the roof of the midbrain does not arise. Similarly, a frog deprived of its hind legs does not develop the hinder region of its brain properly. If an extra limb-bud is grafted on to the side of a newt, it is the sensory nerve-cells, but not the motor cells which are increased in number. Conversely, the motor nerve-cells in the limb-region of the spinal cord become increased in number if an extra brain is grafted into the spinal cord in front of the limb-region. The sensory cells receive their impulses from the limbs, and the motor cells receive their impulses from the brain. The increase in number of nerve-cells in any spe cial region of the nervous system is therefore governed by the number of nervous impulses which these cells receive. Here, again, function controls differentiation, and it becomes easy to see why animals which have certain senses particularly well de veloped also have enlargements of the corresponding regions of the nervous system. Lastly, there is the principle of neurobiotaxis, according to which a nerve-cell tends to move in the direction whence its habitual stimulation by nervous impulses comes. This principle accounts for the intricate internal disposition of the vari ous centres of the nervous system.

Chemical Correlation.

The period of functional differentia tion is essentially one of correlation of the various regions of the organism into one whole, and of an internal struggle between them. Some organs are on a footing of equality with others, others again are related by a system of dominance and subordination. The ef fects of such correlation can be well shown in the case of the sea squirt Perophora. This animal is colonial, and the members of a colony are interconnected by a tube-like structure, the stolon, which is common to them all. If an individual with a portion of stolon is isolated in a glass vessel, the normal dominance of the in dividual over the stolon in the "struggle of the parts" asserts itself, and the latter may be absorbed by the former. In un favourable circumstances, however, the balance may be upset against the individual and in favour of the stolon, which will then grow at the expense of the individual.The correlation of the various parts of the organism is carried out by the nervous system and by the circulation of the internal body-fluid, the blood, which comes to be called the "internal en vironment." The importance of the blood as a correlating agent is based on the presence in it from time to time of chemical sub stances with specific effects (hormones) produced by special (en docrine) glands (or glands of internal secretion). During devel opment, some of these hormones have very important effects. The pituitary produces a secretion which accelerates growth, while the reproductive organ's secretions in birds and mammals play an im portant part in the differentiation of the sexual characters. In frogs and newts, the thyroid gland is of particular interest and im portance, because it is largely concerned in the conversion of the fish-like water-living tadpole into the land-living adult frog or newt. For the details of this phenomenon see METAMORPHOSIS.

External Factors.

In all the cases hitherto considered, the external environment of the developing embryo has been taken as normal and constant. It is, however, of the utmost importance to realize that external factors exert a control over development. Temperature is an important factor which affects the speed at which the chemical reactions which go on during development take place. The various reactions are not all affected by tempera ture to the same extent, so that a rise or fall of temperature may throw the developmental processes out of gear with one another. Sea-urchin embryos grown in a raised temperature, show the anomaly of everting the alimentary canal (forming so-called exo gastrulae) instead of pushing it in.Electric currents have been shown to affect the direction of out growth of nerve-fibres, and they also control the direction of de velopment of the sea-weed Fucus, and the regeneration of the hydroid polyp (Melia, by inducing polarity in them. The chemical concentration of the surrounding medium has a very important effect on development. This can be shown in the case of marine forms, and either by adding certain chemical substances to the water, or by making up artificial sea-water identical with the nor mal except that it lacks some constituent. So, with regard to sea urchins, it is found that chlorine is necessary, or no cleavage of the egg will take place. Calcium is also essential, for without it the blastomeres into which the egg cleaves do not remain together but become separated. Use of this fact is made in the experiments to determine the potencies of isolated blastomeres, which, after separation, continue their development. Addition of lithium to the water has the remarkable effect of suppressing the ectoderm of the gastrula at the expense of the endoderm. Potassium pre vents the larva from developing the skeleton and arms of which they are typical. Perhaps the most remarkable effect of all is obtained after treating very young embryos of the fish Fundulus with solutions of magnesium chloride, chloroform, alcohol or ether. In these cases, instead of the fish developing the normal two eyes, there are varying degrees of fusion between them correspond ing to the strengths of the solutions, until in the extreme cases, like the Cyclops of old, the fish have only one median eye.

The Relation Between Internal and External Factors During Development.—The case of eye-fusion or Cyclopia is of the greatest interest. It shows that fertilization, a proper store of food, and an organizer, are not the sole conditions necessary for the normal development and differentiation of the paired eyes so characteristic of vertebrates. These internal factors, and here must also be included the hereditary factors or Mendelian genes, are powerless to produce anything out of the fertilized egg if the external factors of the environment are not normal. This matter leads on to the consideration of the relative importance of internal and external factors in development, a question often put as the relative value of heredity and environment on the production of the individual.

In the first place, it must be noticed that although the fertilized egg contains a number of hereditary factors, yet, as development proceeds, these are not the only internal factors which the organ ism contains. The possession of the organizer in the newt's egg is an internal factor, but it cannot be said to be inherited, since its appearance is evoked by an external factor, the entrance of the sperm. (The presence of an organizer in eggs which have been stimulated to development by artificial parthenogenesis, and there fore without a sperm, must be due to the establishment of an axial gradient by other means.) New internal factors which were, as such, not inherited, are constantly arising during development, as a result of the interplay between the existing internal factors and the external factors.

There is another point to consider, and that is that while the hereditary factors (see GENE) govern the kinds of structures to which the embryo can by differentiation give rise, yet these hereditary factors cannot of themselves be held to account for the origin of such differentiations. This conclusion follows from the proof that nuclear division during cleavage is not quali tatively unequal, but that on the contrary, all the cells receive an equivalent outfit of hereditary factors. Further, there is the posi tive fact that the quality of the organs differentiated and their positions in the organism depend on their relations to the axial gradients of rate of protoplasmic activities, and these can be shown to be due to external factors acting on the embryo. With out an axial gradient a sea-urchin will not develop although it contains the complete set of hereditary factors.

The conclusions of the preceding paragraphs enable an answer to be given to the old question as to whether development takes place by Preformation or Epigenesis. Of the old crude notion of preformation in the sense of spatial invisible rearrangement, it is no longer necessary to speak. But it is not so easy to dismiss the hereditary material as a non-spatial predetermination. However, it has just been shown that the differentiations which the heredi tary factors may be held to determine, do not arise if external factors have not previously evoked axial gradients. Further, the factors which are operative in the later stages of differentiation (especially the functional period) do not yet exist at the earlier stages. It follows, therefore, that development is a true creation of differentiation in each individual that develops; it is a response to the external factors made by the successive internal factors as and when they arise. As such, development partakes of the na ture of an Epigenesis; the embryo is not preformed in the fertil ized egg. The only proviso which it is necessary to make is that if the embryo is formed at all, the hereditary factors ensure that it belongs to the same species as its parents. In other words, the hereditary factors limit the possibilities of the response which the embryo can make to the external factors.

The connection between parents and embryo by means of the hereditary factors has been compared with a narrow bridge, across which it is very difficult to see how the beautifully delicate ad justments of the fully-developed body can be conveyed. Such ef forts of understanding can however be spared, because it has been shown that the adaptive perfection of the tendons, of the bones, of the blood-vessels, muscles and nervous system, are the result of functional differentiation. They are developments made inde pendently and afresh by each individual of each generation, and the same applies to the relation between the lens and the eye. The correlations take place during ontogeny; they are hot transmitted through phylogeny. The result of these considerations is to throw much of the burden of genetics (in the wide sense) off heredity and on to experimental embryology.

Regulation.

The reader of the foregoing account will al ready have noticed a number of cases of regulation. Isolated blastomeres of the sea-urchin and other forms, blastulae with part of the animal hemisphere cut off, will develop as reduced wholes instead of as incomplete parts. For this to be possible it is neces sary that the embryo when operated upon should still be in a stage when the tissues are plastic, and before the cells have been irrev ocably determined by chemo-differentiation. But the chief prob lem is: how can that which was a part acquire the properties of a whole, especially since it is immaterial what relation the part in question bore to the original whole? To Driesch, this question appeared to be unanswerable in terms of the physical categories of the universe, for which reason he abandoned the attempt to explain development in physicochemical terms. He substituted a vitalistic system of "entelechies," which admittedly placed living processes in a category apart. Unfortunately, this procedure also has the effect of withdrawing the study of development from the possibility of attack and analysis by scientific, and therefore by mechanistic, method. The programme which modern experimental embryology follows, as laid down by its founder Wilhelm Roux, is the splitting up of the processes of development into simpler component processes, of which it may be said that such a result always follows from the action of such and such factors under given conditions. So it may be said that the organizer induces the differentiation of the axial structures in newts and frogs; that the eye-cup induces the differentiation of the lens in Rana fusca; that nerve-fibres react in a definite way to electric currents; that the multiplication of nerve-cells is a function of the number of nervous impulses which they receive; that axial gradients determine the place of and nature of differentiation of various organs, and so on. These components of development may not yet be simple enough to be analyzed by terms of physics and chemistry, but that does not matter. It is already a great step in advance to have a body of fact relating to the biological properties of certain tissues, as ascertained by their biological effects. In this way, experimental embryology or "Entwicklungsmechanik" (developmental me chanics) is becoming an exact science. Now, on turning to regula tion, it becomes important to inquire whether a formal mechanistic explanation is possible, before relegating the problem to a posi tion where it cannot be attacked. For this purpose, a few more cases of regulation will be considered.The case of the blastula of the sea-urchin can be paralleled very closely in the development of the newt. If the ventral half of the blastula of a newt be removed, the dorsal half which contains the organizer will go on developing. When the neural folds arise in such an embryo, they are of the correct size relatively to the reduced size of the embryo ; in other words, regulation has taken place. If the ventral half of the embryo is removed at a later stage however (during gastrulation), the neural folds when they appear are of the original normal size, and therefore quite dispro portionate to the reduced size of the embryo.

Stylaria is a small worm, the head of which occupies the first five segments of the body. Behind the head are the crop and the oesophagus which occupy segments six to eight. If the body is cut across anywhere behind the head, five segments are regenerated from the anterior cut surface, and these undergo differentiation into a new regenerated head. But the alimentary canal of the next three segments, which were part of the ordinary trunk, be comes transformed into crop and oesophagus. This case forcibly suggests the action of axial gradients, which, passing back from the head, have certain relative levels (degrees of intensity of pro toplasmic activities) at which tissues become qualitatively deter mined into crop and oesophagus.

The hydroid polyp Tubularia shows a comparable state of af fairs. If the polyp is cut off, a new one forms beneath the cut surface without regeneration, by transformation in situ of the stem. The polyp contains four distinct zones, and these zones bear fixed proportions to one another as regards their width. But the whole reformed polyp bears a relation to the length of the whole piece of stem, and what is more, the size of the polyp can be controlled by external factors which are known to affect proto plasmic rates of activities, and therefore the axial gradients. These cases of regulation therefore suggest that axial gradients are some how involved in the problem. Now reverting to the proposition to the effect that the fate of a cell is governed by its position with regard to the whole organism and to its axial gradients, it is only necessary to assume that the levels on the gradient at which particular differentiations are evoked, have a relative and not an absolute value, in order to arrive at a mechanistic formal expla nation of regulation. Actually, this is no assumption, but a state ment of fact, for there is considerable experimental evidence from the quality of regenerates of pieces of the worms Planaria and Lumbriculus, to show that it is relative rates of protoplasmic activities, or in other words the steepness of the axial gradient, which are responsible for the quality of thF; differentiation.

Lastly, it is necessary to guard against the danger of exaggerat ing the effects of regulation. Thus, the vegetative half of a gas trula of a sea-urchin is by itself capable of forming a little gastrula, but such a gastrula is deficient in that it possesses no mouth. This follows from the fact that the organ-forming substance for a mouth is already determined and restricted to the upper or animal portion of embryo from a very early stage. There is therefore a simple mechanistic explanation for the absence of a mouth in these operated embryos. But on the vitalistic theory of entelechies, it is inconceivable why the regulating principle, which is supposedly responsible for the perfection of the embryo, should fail in this respect.