Experimental Psychology

EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY is a method of study ing psychological problems and is not to be regarded as itself con stituting separate subject-matter. It is a systematic attempt to determine the conditions of animal and human conduct by the arrangement and variation of typical situations in response to which such conduct normally occurs. Like every other science it is thus primarily concerned with the discovery of causal laws opens ating within the field of its study. Experimental psychology does not, so long as it keeps within its proper limits, speculate as to the exact nature of the materials with the relation of which to their stimuli it is directly concerned—that is, with sensations, images, ideas, judgments, trains of reasoning, feelings, emotions, senti ments, impulses, volitions—but it does set out to find the condi tions for the occurrence of all of these, and to explain how, when they have occurred, they may themselves operate as conditions of subsequent conduct. Moreover, the experimental psychologist professes to deal with conduct as it occurs in the intact organism, and the implications of this are now coming to be much more completely realized than was the case a few years ago. Many of his problems appear to be similar to those of the physiologist. Both alike, for example, study the conditions of visual and audi tory reactions. But the physiologist is largely concerned directly with the reactions of the special sensory apparatus involved. Whenever possible he can legitimately isolate this and consider what occurs within it when various stimuli are being brought to bear upon it as giving an answer to his questions. The experi mental psychologist is concerned with the reaction to similar stimuli, not, for instance, of the eye alone, but of the visual mechanism in its intimate relations to the conduct of the rest of the organism. Naturally this renders his problems very much more complex and his solutions at present have to be expressed more tentatively, more contingently.

Sources.

Experimental psychology as a systematic study grew out of the work of physicists and physiologists who were compelled to recognize the important part played by the human observer in the results which they obtained from their experi ments. Thus it was at first almost entirely concerned with the measurement of "reaction-times"—i.e., the time elapsing between the giving of a stimulus and the making of a prescribed response by the observer—and with a study of the special senses. In a brief survey it is impossible even to mention the names of many pfoneers whose work gradually developed modern methods of experiment in psychology. A very great amount was due to Gustav Theodor Fechner, however, who, appointed professor of physics at Leipzig in 1834, elaborately endeavoured to obtain exact quan titative statements of the relation between the intensity of a stimulus and of the sensation which it evokes. His reasoning has never commanded wide assent, but the actual methods of observa tion which he initiated have been developed in many ways and are the foundation of a large part of modern experimental pro cedure. In 1885 Hermann Ebbinghaus published the results of a long series of experiments which he had made upon himself in the memorizing of nonsense syllables. He claimed that the use of this kind of material made it possible for the first time to experiment successfully on the "higher mental processes." Although, as in the case of Fechner, there is reason for doubting the validity of many of his claims, his work undoubtedly inspired a large quantity of further research. Near the beginning of the present century Os wald Kiilpe took a further step by encouraging a number of re searches upon judgment and volition, while throughout the whole period, from Fechner onwards, experimental work on feelings and on certain specific psychophysical problems, such as that of fatigue, have been continued. In England the approach to experi mental work in psychology has been, from the time of Francis Galton, in general by a biological route. The importance of sta tistics as a method of dealing with experimental results has re ceived special attention and in many ways experimental psychol ogy has been closely in touch with neurology and medicine.It is curious that the genuine experimental study of animal behaviour is a very recent growth. With a few exceptions, and those for the most part due to the interest of comparative anato mists in the localization of various bodily functions, the anecdotal method of Aristotle remained predominant in the study of animals till the present day. That there is now a flourishing school for the experimental study of animal behaviour is due in the main to America and in particular to Edward L. Thorndike, Robert Yerkes and John B. Watson.

The Present Status of Experimental Psychology.—There is now no important university anywhere in the modern world but in some way recognizes the right of experimental method in psychology to a position in the scheme of higher education and of scientific research. Most of the leading universities, at least in America, Great Britain, Holland, Germany, France, in most of the British colonies and, to a rapidly increasing extent in Russia, China and Japan, provide actual experimental laboratories, though there is still room for much improvement in this respect. A considerable number of well-established journals exist for the publication of the results of experimental research in psychology. Apart from university teaching there are, in almost every vigorous modern nation, flourishing organizations for the practical applica tion of psychology in various directions, particularly those of edu cation and industry. There is a rapidly growing recognition of the importance of psychological teaching and research in relation to the practice of medicine and law and to the organization of a country's defensive and offensive services. It would be easy to show that the development of this practical aspect of psychology has been made possible directly and almost entirely by the use of experimental methods.

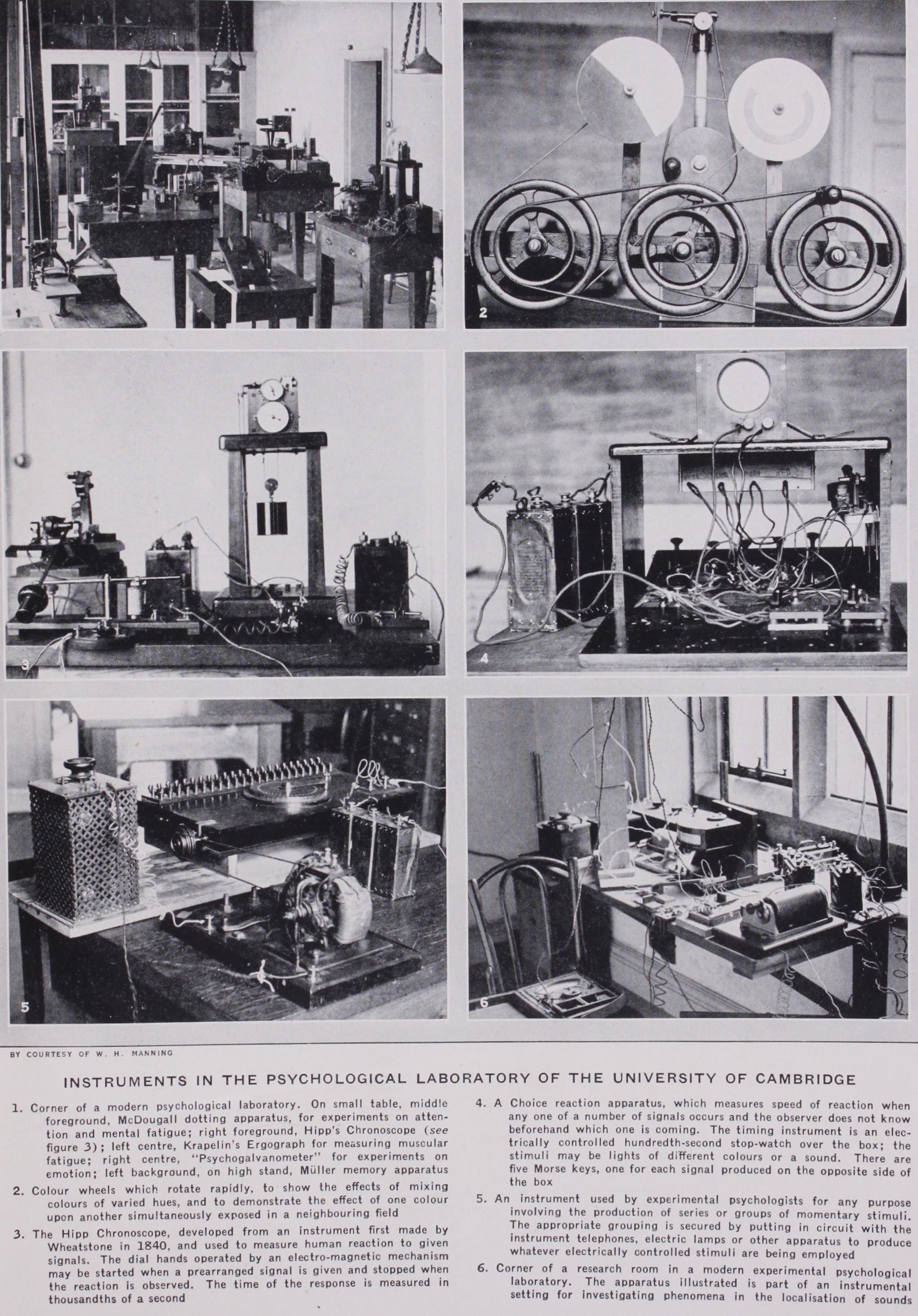

The Psychological Laboratory.

It is still true to say, how ever, that the majority of people who are interested in psychology in a general way have never seen the inside of a psychological lab oratory and are somewhat puzzled to think what problems the experimental psychologist investigates and how he proceeds. In the accompanying plate are reproduced photographs of some of the apparatus which experimental psychologists frequently use. Only a very small selection can be reproduced in this way, how ever, and it will therefore be of interest to describe certain typical equipment and methods as they are to be found, or as they are employed in any modern laboratory devoted to psychological work.As has been stated already the earliest experimental psycholo gists were physicists and physiologists and consequently a great amount of work in the psychological laboratory is concerned with the special senses of touch, temperature, taste, smell, vision, hearing and movement. Let us select two groups of these, for a somewhat more careful description; those dealing with visual and those dealing with auditory reactions. Here, then, are colour wheels on which discs of different colours may be rotated so rap idly that the resulting sensations combine and the effects of mixing colours in varying proportion can be accurately determined. Special apparatus demonstrates the after effects of continued light and colour stimulation, and the occurrence of colour blind or colour weak zones in the normal eye. A dark room is provided designed to show clearly the differences between vision in daylight and in twilight and to bring out some of the theoretically and practically important facts connected with abnormalities of colour vision and with night blindness. All of these may be seen in the physics laboratory or in the physiological laboratory. But the psychologist now realizes that his main problems and his methods of approach are his own. The physicist is chiefly concerned with an analysis of the stimulus, the physiologist with the mode of re action of the eye itself, for instance, and with its connections with the central nervous system. The psychologist must be concerned with these also but has all the time to keep clearly in view how the accuracy of the observations themselves is determined. Thus he has to be particularly careful to study the effects of the method and order of presentation of the stimuli. He knows that these and numerous other factors, some of which may be extraneous to the particular experiment involved, determine the observer's atti tude towards what is set before him, and that this general attitude for which there is no obvious or immediately available physical or physiological expression, in turn may powerfully influence his observations.

With the same aim the psychologist carries out experiments on sound. He notices a man's normal reactions to sounds of different pitch, intensity and complexity, studies the results of combining tones in various ways, measures the acuteness of an observer's re action to sounds of given character, and demonstrates how the ears make it possible to judge where a sound has its source. He shows how all these apparently simple responses are in reality ex ceedingly complex and how an important part of their conditions often has to be stated in terms of what are called the "higher mental processes." But obviously the world in which men live is not mainly a world of shifting patches of light and shade, of colour, of isolated sounds, tastes, smells and similar sensory characters. It is a world of things identified, named, referred to some position in space, or apprehended as moving in some direction. So the experi mental psychologist must try to show the conditions, not only of the relatively abstract sensory response, but of the more concrete perceptual processes that men are constantly carrying out. He has apparatus for the controlled exposure of objects : stereoscopes and devices for the study of the perception of solidity or of dis tance, and of the various optical illusions ; means by which he can demonstrate how sensations of differing kinds may all come together into a single complex perception.

A very little study of these perceptual processes is enough to demonstrate that in many instances what is actually perceived at the moment is only a little of what a person reports that he has observed. We fill up the gaps of perceptual data by using images, or relying upon recollection, in some form, of past events, as when a person, travelling at high speed in an express train sees only parts of things through the carriage window and then reports his observations with much more detail than could possibly have been discriminated at the time. Considering this the experimental psychologist is led to arrange special situations with a view to the production of mental imagery and to study the types and f unc tions of the imagery produced. Once more employing his exposure apparatus, so that the conditions of reaction can be at least par tially controlled, he presents common objects incomplete in some respects, or material arranged in a series which gradually ap proaches a climax, or material directly designed to produce am biguous or alternating reactions, or material conflicting with some other simultaneously presented perceptual data, and in these and other ways seeks to arouse mental imagery and so to discover what functions it fulfils.

It is now but a little step to the study of memory proper. Here a vast field of research, with its own peculiar technique in the construction and presentation of material to be memorized, is opened up. The experimenter has to investigate economical methods of learning, rates of forgetting, the influence of specific factors such as position in a series upon immediate and remote recall, and to try to measure association strengths between items presented simultaneously or in succession. For all this he has his specially devised material, his specially arranged methods and his specially constructed apparatus.

Throughout the whole range of psychological experiment an observer frequently has to judge, to choose, to decide, and often reports that his reaction processes are accompanied by feelings and emotions. How can these functions of judging, choosing, decid ing and feeling be themselves experimented upon? As regards the first three of them the essential method is to place an observer in some situation which sets him an interesting problem. The solution has to be effected by judgment, choice or decision. Thereupon the experimentalist brings into play apparatus by which he can record some of the physiological changes which accompany these mental processes, such as variations in respiration, in pulse rate, or in glandular secretion. At the same time the observer, acting throughout under relatively controlled conditions, gives a verbal report of the processes which seem to him to have led up to the judgment, or the choice, or the volition. The problem situations may be indefinitely varied in complexity, from the simple judg ment as to which of two weights is the heavier to decisions upon controversial questions of great difficulty. In regard to feeling also some exciting stimulus or situation is presented, and the observer reports verbally the factors which appear to induce his feeling, while changes of respiration, of pulse beat, of glandular secretion, of resistance to the passing through the observer's body of an electric current and so on, are recorded.

As a part of practically all of the general fields of investigation already mentioned it is of ten of interest to measure the speed at which the combination of physical, physiological and psychological processes involved takes place. For this purpose the psychologist has developed elaborate and delicate "reaction-time" apparatus by which he can determine, up to a thousandth of a second, the time elapsing between the occurrence of a stimulus and the response to that stimulus in some pre-arranged manner.

Especially interesting questions arise in the investigation of abnormal conditions. What, for instance, are the effects of glare, or of flicker in the visual field ; of excessive and continued noise or vibration in the auditory and tactual fields ; of drugs and fatigue upon psychical processes generally? The study of muscular and mental fatigue in particular has developed a mass of special ap paratus and methods of research and has an immediate practical application.

In nearly all cases of psychological experiment very little reli ance can be placed upon single and isolated observations. The con ditions involved are always complex, always only partially con trolled. Repeated observations are necessary. If these are to be successfully interpreted the experimentalist must be well ac quainted with the technique of the "psychophysical methods," and he must have some knowledge of statistical theory and practice.

The experimental psychologist has no lack of problems with which to concern himself. In all the directions mentioned and in many others the application of experimental method is as yet in its infancy. The greatest success has so far been won in the realm of the study of the special senses and of perception. But his methods and results are now extending rapidly. More and more the higher mental processes are coming within the experimental ist's purview, so far as knowledge and control of their conditions are concerned.

In one direction in particular it is highly probable that the near future may see important advances. A great many of the condi tions of our conduct are directly social in character and source. There has been little attempt to observe these under experimental conditions, but the task is by no means hopeless. We can so ar range experiments as to be able to observe at least some of the effects of socially derived motives : competition, pugnacity, asser tiveness, submissiveness, friendliness, liability to suggestion and the like. The results obtained in this way must inevitably react upon the experimentalist's study of the individual, forcing him to investigate not only the operations of the intellectual, cognitive mechanism, but also the extremely important play of tempera ment and character. In some ways the most striking achievement of the experimental psychologist in recent years has been the de velopment of exact methods of studying and ranking "intelli gence." These may well be supplemented in the near future by more exact methods for the study of the social determination of conduct and the influence of individual temperament.

The Contemporary Situation.

A considerable change has come over experimental psychology since its early days. Then the chief aim was to render a description of certain experiences as they were experimentally produced and controlled. On the one hand the interpretation of the results obtained was dominated by theories taken over from general psychology according to which all complex experiences were regarded as made up of unitary ele ments of a sensory order which had been built together in the course of individual life by the "principles of association." On the other hand the actual methods employed were, as nearly as possible, copied from other experimental fields. Particular forms or varieties of experience, whether of a sensory, or of a "higher" order were, as far as possible, cut off from other kinds and cor related with their immediate physical stimulus. The result was often artificial in the extreme and experimental psychologists were constantly doing or initiating work which could be done much better by physiologists, with their specific training in the technique of the study of relatively isolated bodily activities. The view that complex experiences and reactions are genuinely aggregations of simpler forms has now practically disappeared. In consequence the problems of the experimental psychological laboratory have been brought very much nearer those of real life and, as has been indicated already, the experimental psychologist has developed a technique and a point of view which are as distinctive as they are effective.A very powerful influence in bringing about this change has been the movement known as "Behaviourism" (q.v.). Men have always been interested in the study of the behaviour of animals. But until very recently their interest led them either to the descrip tive type of study attempted by the field naturalist, or to the col lection of remarkable animal stories interpreted in the light of human conscious experience. The development of an experi mental approach to biology made "behaviourism" possible. At first, as in the field of general human psychology, experiments were mainly concerned with the special senses, and in particular with an anatomical study of the parts of the central nervous system in which various special sensory reactions, of sound, vision, taste, balance and the like may appear to be localized. Then experi menters began to try to observe exactly bow various species of animals learn to discriminate one object from another, or to run successfully more or less complicated pathways in a maze. They decided to avoid explaining animal conduct in terms of human experience, and to limit themselves strictly to relating the condi tions of their experiments, as any competent observer would de scribe them, to the conduct of the animals, as that, again, could be described by any instructed on-looker. It seemed possible to do a great amount, and perhaps the whole of this without once using the notion of consciousness as a causal factor, for these experimenters rightly held that to attribute consciousness to an animal is to go beyond directly observable fact. Their success led them to put forward an exactly similar programme for experi mental work in general human psychology.

Most experimentalists in psychology, however, still maintain their right to include in the conditions of the reactions which they study many that are, certainly for the present and it may be f or ever, incapable of being expressed in physiological terms. Many attempt to hold themselves free from any systematic theory about the nature of human experience and, taking up certain specific problems of reaction in human beings, insist that such re actions must be regarded as part determined by "attitudes," both conscious and unconscious, by "tendencies" whether instinctive or of a higher level, and by the accumulation of the results of past experience which appear or which function in the form of images, ideas, sentiments and so on. For example, much work is still being done on the minimal intensity of stimuli of varying quality which will produce a reaction. The experimental psychologist shows that these "threshold values" of stimuli of all kinds can be shown to depend in part upon "attitudes," images and like factors occur ring during the course of the experimental investigation. He holds that, independently of any discussion as to their ultimate char acter, it is impossible at present to reduce these to physiological and much less to physicochemical terms. Such a view being admitted experimental laboratories are to-day investigating prob lems over the whole field of human response. There is a revived interest, due largely to certain important practical difficulties which arose during the World War, in the psychology of the spe cial senses, particularly those of vision and hearing. The image processes and their relation to perceptual reactions are the subject of constant experimental study. Memory is being investigated, less as an isolated type of response, and more as falling into place in a whole complex learning-process which may continually in volve also the higher mental activities of judging, choosing, reason ing and the like. On the side of 'feeling and emotion increased interest in experiment has grown out of recent work on the effects of the secretions of endocrine glands. Methods of registering emo tional expression through metabolic change are being further developed, and both in this field and in that of volition some psychologists expect much from the use of the galvanometer which appears to be capable of being used to indicate when cer tain changes commonly called mental take place.

In general the evidence seems to be going against strict be haviourism as a tenable theory. Towards this conclusion the ex perimental researches of the Gestalt school, as it is often called, have greatly contributed. Professor Max Wertheimer, followed by Professors Wolfgang Kohler and Kurt Koffka and many others, starting from some striking experiments on the way in which the perception of movement may be produced, have urged that it is impossible to consider the phenomena of perception as in any way made up of a number of isolable elements whether of sen sory or of any other origin. We perceive "forms," "shapes," "con figurations," which are doubtless complex, but whose character considered as a whole gives them their properties and their func tions. The theory has been worked out most fully in the realms of visual and auditory perception, but as applied to problems of con duct it is clearly diametrically opposed to an interpretation which treats complex behaviour as the expression of numerous simple and relatively self-contained reflexes. The view that all high level forms of activity possess characteristics of their own, in no way theoretically deducible from a study of the simpler conduct out of which they have undoubtedly developed is also in line with a mass of research of a more physiological and neurological order.

In whatever realm and with whatever general background of theory he works, however, the modern experimental psychologist is definitely committed to a biological method of approach. He regards mental processes as falling into their place in a biological adaptation of the organism to its environment, and his problems are thus becoming more and more an enquiry into the functions which such processes carry out, and less and less a mere descrip tion or a mere analysis of the processes themselves.

Modern Practical Applications.

A very few remarks may be added concerning current practical applications of experi mental method. The application of experimental psychology to the solution of practical problems was strongly stimulated by the World War. During that period of time every important belligerent country called upon its psychologists for advice in the development, organization and training of its offensive and defensive forces. Much of the work then done continued and has been developed in many different ways. In industry psychologists have their special tests for vocational aptitudes and their methods of vocational guidance and training. The regulation of bodily movements, organization against "fatigue," and the study of accident liability have direct application both to the fighting services and to many departments of industrial work. In education the "intelligence test" movement has grown to enormous dimensions. In medicine the study of abnormal con duct and its explanation both by organic lesion and by functional disability for which no satisfactory organic lesion can readily be found have been rendered easier and more definite by the union of experimental method with clinical observation. In legal prac tice psychological experiments have been tentatively proposed and used in connection with the detection of crime.The whole of this practical development has reacted power fully upon those methods of academic research without which it could itself never have grown to importance. In this way also the laboratory has been brought nearer to the problems of real life, and the very great possibilities of experiment as contributing to a more complete understanding of man's multifarious activities is being explored with greater eagerness than ever before.