Exports in Practice

EXPORTS IN PRACTICE There are two principals to an export transaction, although neither need have definite knowledge of the other. One is the manufacturer, producer or factor with goods to export; the other is the wholesale distributor in the importing country. Between them exists the export machine consisting of various intermedi aries and services, by means of which buyers can maintain effec tive touch with all sources of supply, while manufacturers are enabled to supply in many scattered markets the needs of cus tomers whom they would never otherwise reach, whose require ments they could never discover, and whose credentials they could not test. The machine performs this comprehensive task by co ordinating three distinct lines of effort: (I) selling, buying and distribution; (2) transport ; and (3) finance and insurance.

Two Basic Export Systems.

For selling, buying and distrib uting two different, yet parallel, systems are employed. One is more closely identified with British practice, and the other with American, though neither is a national monopoly. The broad difference between the two is that under the British system the manufacturer's immediate customers are merchant-shippers or commission buying agents established at his door, who accept all financial responsibility for the orders they place in fulfilment of indents received from their importing clients overseas; while un der the American system the intermediaries are commission selling houses acting on behalf of groups of manufacturers, and combin ing the functions of merchant-shippers and sales representatives. Even these two systems leave some gaps, particularly in regard to certain markets which lack wholesale distributing firms of suffi cient importance or which present credit difficulties of an excep tional nature. In American practice these difficulties have been largely overcome by the use of financing with drafts drawn D/P (documents against payment), with foreign sales agents used to re-sell and re-ship goods on which payment is refused and title to which is consequently not transferred. Such territories often fail to attract the enterprise of selling organizations, whose energies are absorbed by safer and larger markets ; while the same draw backs render commission buying agents in London, Paris, or New York unwilling to assume responsibility for traders in countries which lack sound or comprehensive importing systems. In these relatively few cases, the manufacturer or shipper desiring to do business with the countries concerned has to devise special and more or less direct methods, safeguarding himself as well as he can by such devices as the del credere agency system, which has for years been used considerably in Egypt, and under which a local agent undertakes financial responsibility for the orders he forwards, and is remunerated by a correspondingly higher rate of commission. In South Africa a London "confirming house" will undertake for a small commission to guarantee payment of drafts drawn on consignees.

The Merchant-Shipper.

The merchant-shipper and the com mission buying agent exist side by side, and in modern times their duties have become so closely related as to be in part identical. The former is an independent trader, definitely a middleman, tak ing such profit as he can make, initiating his own selling efforts abroad, and acting as a principal toward his customers. He is the heir of a system as old as civilization itself, but changing condi tions have compelled him to change with them. Whereas he once had the entire world to serve, in the 19th century he was con fronted by the growth of a new order of things. Among his cus tomers in such markets as the principal British dominions, the South American republics, and similar progressive countries, were many importing houses whose turnover became so extensive that they were in a position to go direct to manufacturers, and to per form for themselves the duties previously undertaken for them by merchant-shippers. In many cases, too, these importers were urged to this change by the competition of great trading companies with headquarters in Europe, and widely distributed branches or stations. They therefore established their own buying and ship ping houses in supplying centres, or appointed agents to act for them. The merchant-shipper thus found his scope becoming more and more limited, with—apart from certain special lines of busi ness—only undeveloped markets, and the smaller importing ac counts in the larger markets, offering him business on the old lines. Consequently, he has to an increasing extent been compelled to combine the work of commission buying with his more inde pendent shipping operations.

The Commission Buying Agent.

Under the commission buying system an agent may act for a number of overseas import ing firms, usually confined to only one or two markets. The pro cedure is for them to indent on him, an indent being an instruction to buy certain goods, and is not in itself an order. The agent acts on this instruction, buying the goods on quotations obtained from various manufacturers, arranging for their packing and shipment, and paying the accounts of manufacturers and ship-owners, 'for which he makes himself responsible. For these services he re ceives an average commission of 21%, though it may vary ac cording to the nature of the goods. He usually passes discounts and rebates to the importers for whom he buys. In the U.S.A. both merchant shippers and commission buying agents have prac tically disappeared.

The Commission Selling Agent.

With the commission buy ing system so strongly entrenched, the export selling agency has not found much room for development in Great Britain, nor in certain European countries, but in the United States of America and in Canada it largely prevails. Its advantage lies in its active efficiency as a selling force on behalf of manufacturers; its prin cipal defect lies in the virtual impossibility for a single concern to have a sufficiently expert and intimate acquaintance with buyers in all markets, to be able to arrange credits safely, or to cover the ground with adequate selling effort. In practice a certain amount of specialization occurs from necessity rather than intention. An export selling house may be formed as the result of a number of manufacturers of allied goods combining for the purpose, or an independent agency firm may obtain the sole right to sell on com mission abroad the goods of a similar series of manufacturers. Such a concern attends to selling, shipment, payments and credits, etc., on behalf of its principals. In the U.S.A. the export com mission house sometimes performs both the functions of the com mission buying agent and the commission selling agent.

The Manufacturer's Export Department.

Under the mer chant-shipping and commission buying systems it is clear that no selling force operates on behalf of the manufacturer, and he is therefore compelled to provide his own. He begins, probably, by employing a special representative to solicit orders from the buy ing houses who are in receipt of indents for his class of goods. Then the need will become apparent for getting particular brands specified in the indents sent home by overseas importers, or it will prove advisable to find further methods of stimulating busi ness, so commission agents travelling in the markets served will be employed. Such agents usually represent a number of manu facturers, confine themselves to one market or group of markets, and call only on wholesale importers. Their mission is not to ac cept orders direct, but to persuade importers to specify certain goods when indenting on the commission buyers. (In the U.S.A. the practice of direct distribution abroad through foreign resident selling agents or to foreign import merchants or wholesalers, has practically superseded.) The manufacturer is informed by his agent concerning each promised order, and then seeks confirma tion of it from the buying house concerned. The agent is paid corn mission on all the orders received for shipment to the territory covered by him, and frequently obtains in addition a contribution toward his expenses from each of the manufacturers he represents. An alternative method is to employ an export agent who has headquarters in the supplying country, and who performs the en tire work of sending representatives abroad and obtaining con firmation of the indents they influence.In a few special trades, of course, and in a few specially condi tioned markets, it is possible for the manufacturer to solicit orders directly, and to ship the goods without the intervention of any intermediaries. On the whole, however, direct export trading of this kind is regarded as inexpedient and dangerous. It is obvious too that the direct shipper is almost certain to be barred from the preponderant proportion of shipments controlled by merchant shippers and agents, and must recognize that the range of his pos sible clientele will be severely limited. In this practice, factory representatives are sent abroad to select distributors, in lines where intensive sales effort is necessary, and train them in distri bution, demonstration, and creating consumer demand.

Shipping Methods, Finance and Insurance.

The actual work of shipping is the same if performed either by manufacturer, merchant-shipper or commission agent. It involves the arrange ment of freight with shipowners, packing, carriage to the docks, . and perhaps forwarding from an inland centre, the preparation of consular invoices and customs declarations, the receipt and mail ing of shipping documents, possibly the hypothecation of the latter, and the insurance of the consignment.

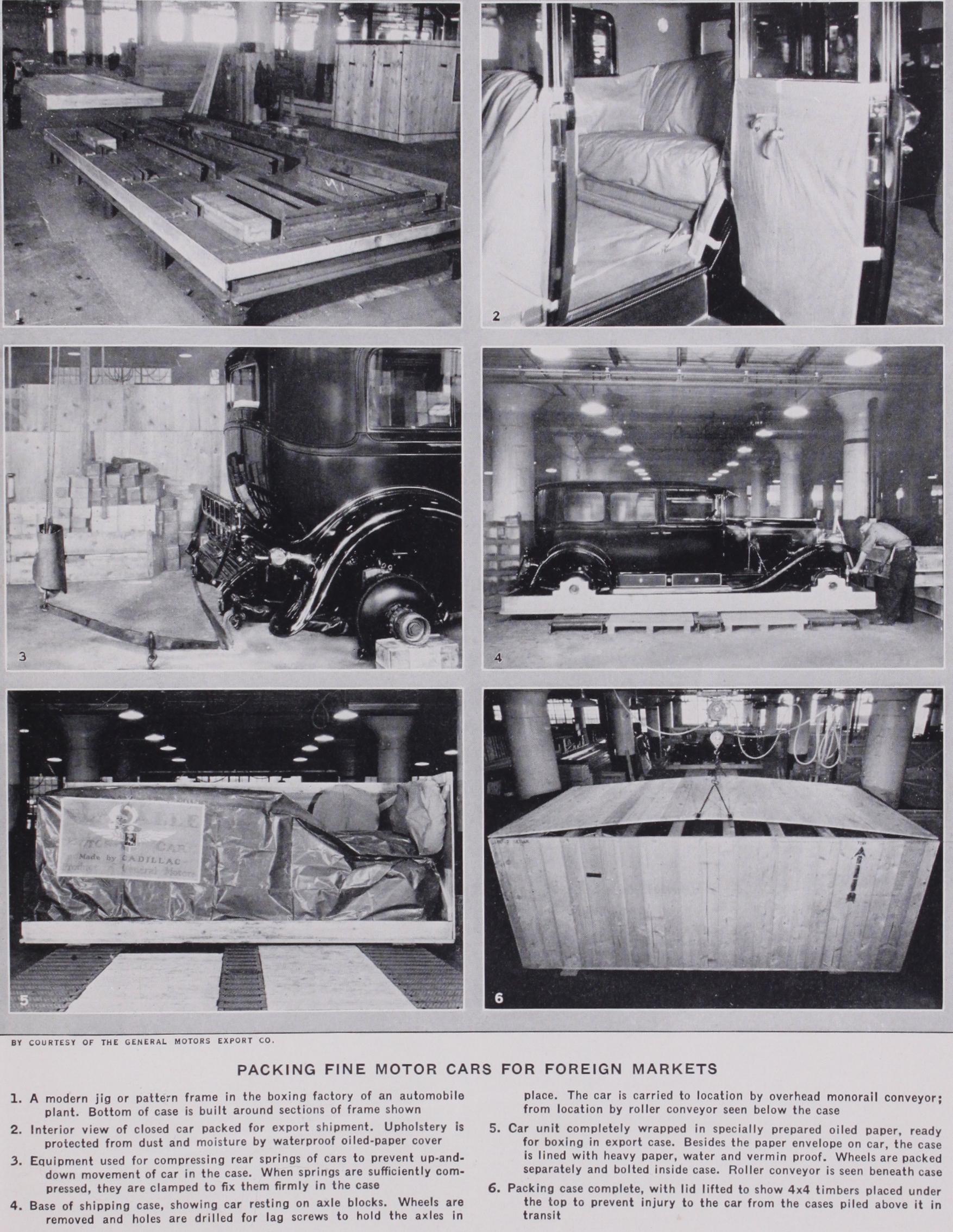

Packing for Shipment.

This is a matter beset with special requirements for different markets, and even for different con signees. So far as these are concerned, the instructions of the indentor can be the only guide apart from knowledge of a pre vailing custom. Goods are baled or cased according to their nature, baling being the cheaper, and the first step in either method is "making-up" or "knocking-down," the former term covering the folding, marking and ticketing of textiles, and the latter the sepa ration into convenient parts of certain types of furniture, or the dismounting of machinery. The goods are then arranged in com pact lots for measurement, and the case or baling material pre pared to suit. If this work is done by a specialist packing firm, full instructions must accompany the goods, which should be in spected by the shipper when ready to close down. Marking is done in large stencilled letters, the consignee's "mark" and port of destination being placed on at least two sides of each pack age. The bales or cases are then handed over to a carrier for transport to the docks, where they are weighed or measured, and a "weight note" is handed to the carrier, this constituting in some circumstances a certificate of delivery, and even going forward with the shipping documents.

Shipping.

Before this stage is reached the shipper arranges freight with a shipowner or shipping company. For a special cargo it may be necessary to charter a vessel, and for this a charter-party is prepared. This document provides on the one side that the ship shall be seaworthy, properly equipped and waiting at the specified port by a certain date ; while the charterer agrees to load promptly, pay the charges due, and use the vessel for a definite voyage, or as he desires during a definite period.The general shipper, however, simply arranges for freight space on a ship sailing with other cargo. He does this at a fixed rate per ton, the shipowner retaining the right to charge on ton weight or ton-measurement, the latter being 4o cu.ft. per ton, and used for light or bulky goods. To the carrying rate is added "primage," for the use of the ship's cargo-handling machinery. "Primage and average accustomed" indicates a pro rata charge on each consignor. On embarkation a "mate's receipt" (called "dock" receipt in the U.S.A.) is obtained, and this is exchanged later for a bill of lading. The latter is made out in several "parts" or copies, one of which is sent to the consignee by an earlier or faster vessel to insure prompt delivery of the goods on arrival. The first "part" (known in the U.S.A. as the "original") pre sented is the only effective one. Such a bill of lading is known in American practice as a "straight" bill of lading. If it is made "to order of the shipper," and not in a particular consignee's name, it must be endorsed by the shipper before it becomes valid or negotiable.

Freight Terms.

Closely connected with the question of freight rates is that of quoting prices for export, as manufacturing costs and shipping charges obviously have to be joined at some point before the consumer of the goods is reached. There is a multitude of terms, each with some interesting variation of mean ing, but the two basic methods of quoting are "Free on Board" and "Cost, Insurance and Freight," usually indicated as "F.O.B." and "C.I.F." (qq.v.).

Marine Insurance.

The fact that ownership in a consign ment rests in the consignee from the moment of shipment makes it necessary for any insurance policy to be taken out in his name, the shipper again doing this as his agent. On this subject it is sufficient to say that there are two principal classes of risks. One is "With Particular Average" ("Particular" means "partial" and "Average" means "loss" in this case), which covers all risks, in cluding damage and loss by disaster to the vessel, by exposure to heat or water, and by rough handling or accident, all resulting from "perils of the sea," not negligence. The second is "Free of Particular Average," and is limited to total loss, being usually adopted to cover rough goods. Some goods subject to heavy par tial loss, such as chinaware, may be insured "With Particular Average up to —%," which means that if more than that per cent is damaged it is not insured. "General Average" is another term referring to loss incurred in preserving the vessel or cargo and involves a pro rata payment by all consignees.