Foreign Exchange

EXCHANGE, FOREIGN. Foreign exchange, as its name implies, relates to the purchase and sale of foreign moneys. The subject includes the interpretation and significance of "rates of exchange," the operation of the foreign exchange market, and, on the more theoretical side, the reasons why a particular currency is bought or sold, and all the factors accounting for its supply and demand. These last form part of the general science of economics, and also react upon the more practical questions of trade, invest ment and interest rates.

A rate of exchange between two countries is the price of one country's currency expressed in terms of the other's. From this it would seem that there are two alternative ways of expressing the rate, e.g., f 1 =$4.866, or $1 = 494 pence. By custom, only one of these ways is adopted. Thus, in New York, all rates except sterling are quoted in cents per unit of foreign currency. In Lon don, most rates are quoted in foreign currency per pound sterling, but the Lisbon, Eastern and most South American rates are quoted in pence per unit of foreign currency. To cite a few examples, Paris would be quoted, say, frs. 121, Rome lire 92, but Bombay at is.6d. (per rupee) and Brazil at 7d. (per milreis). As regards British Empire rates, Canada is quoted in dollars per pound sterling, and the Australian and New Zealand quotations express the price in London of f I oo in Australia or New Zealand. The South African exchange is quoted both ways, i.e., "on London," or money in London; or "on South Africa," i.e., money in South Africa.

The next point to consider is what it means when a rate goes up or down. Confining this analysis to London, a sharp distinc tion must be made between the "foreign currency" rates and the "penny" rates. In the first instance, a rise in the rate, say from $4.86 to $4.87, or from frs. 120 to frs. 121, means that the price of the foreign currency has cheapened, or that, in the jargon of the market, the rate has moved "in favour of" England and "against" America or France. In the second instance, a rise in the rate, say from is.6d. to is. for the rupee, obviously means exactly the reverse. The test of a "favourable" or "un favourable" movement is whether the country's currency has risen or fallen in price.

It will probably be simplest to abandon for the moment further consideration of the technicalities of rates and to consider the im mediate causes of their rise or fall. For this purpose, it will be easiest to consider two countries alone, such as England and America, though it must be remembered that in practice the rate between two given countries is affected by developments else where in the world.

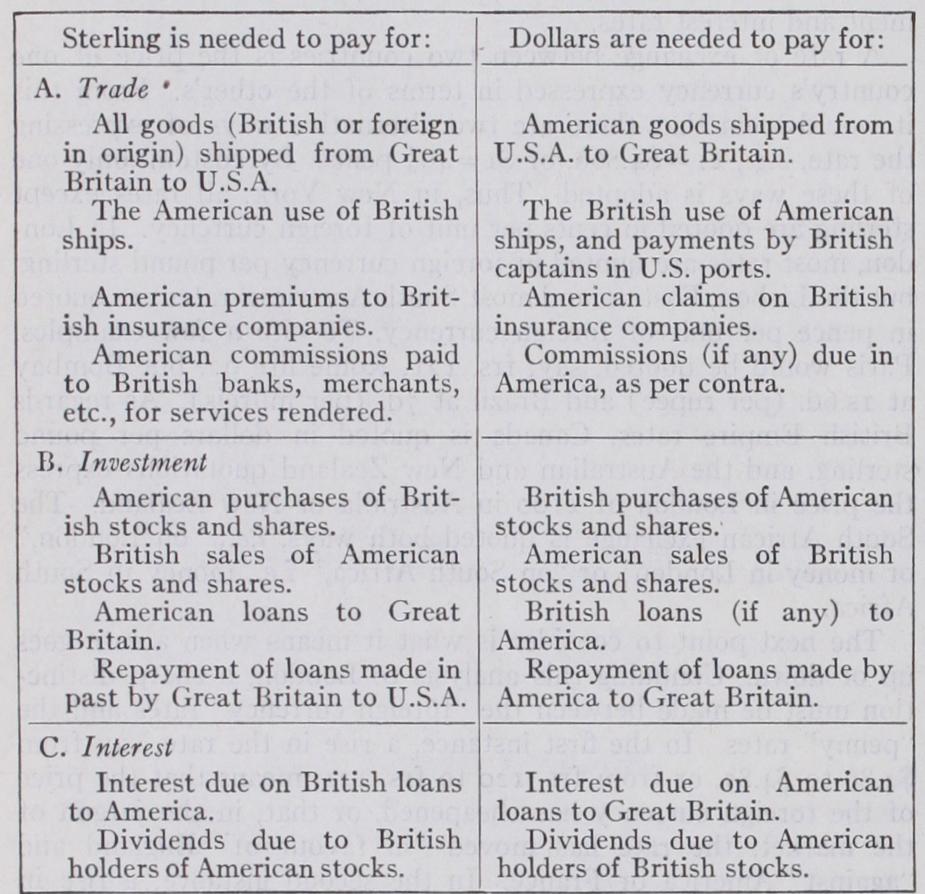

Foreign Exchange: Supply and Demand.--A

rise in the dollar rate in London means that dollars have become cheaper and pounds dearer, while a fall means the reverse. There can be only one cause of such a rise, namely, that more people wish to buy pounds in exchange for dollars than wish to buy dollars in ex change for pounds ; so the next thing to see is who wishes to buy pounds or dollars at all. The answer is clear. The pound alone is legal tender in England, and the dollar alone is legal tender in the United States. Everyone who has goods to buy, money to invest, debts to pay or money to lend in England must buy pounds, and everyone who wishes to do any of these things in the United States must buy dollars. The Liverpool importer of cotton from the United States must buy dollars. The London buyer of "American rails" must buy dollars. The British Government, when paying interest or sinking fund on the war debt, must buy dollars. The London stock-broker who sells British war loan on behalf of an American client must buy dollars, for he has to pay the proceeds to his client in dollars. The British fire insur ance company which has to meet an American claim must buy dollars. Conversely, the American exporter of goods to Japan or the Fiji Islands, who sends them in a British ship, must buy sterling, so as to pay his freight. The American importer of Man chester goods, or even of French lace sold to him by a London merchant, must buy sterling. The American who insures himself with a British company must buy sterling every time he pays his premium. The American tourist in England must buy sterling to pay his hotel bill. The American trader who sends his bills to London for acceptance must buy sterling to pay his commission to the London accepting house. The American buyer of British stocks and shares must buy sterling so as to pay for them. The American railroad company with British shareholders on its reg ister must buy sterling so as to pay their dividends.These examples can be multiplied indefinitely, but can be sum marized more conveniently in the following table :— The next point is to see how these various traders, investors. etc., acquire in practice the sterling or dollars that they need. The basic, though least common, means of making payment is in gold. By English law, one gold sovereign contains 123.274 grains of gold, eleven-twelfths fine; and by American law, one dollar contains 25.8 grains of gold, nine-tenths fine. The Bank of England in London engages to buy all gold offered to it at 77s.9d. per ounce, eleven-twelfths fine, while the Treasury in Washington will also buy gold at the appropriate rate. Also gold is legal tender in both countries. Hence anyone in America owing money in England can pay by tendering the weight of gold corresponding to the sum he owes at the above legal rates.

Gold Points.

This is of importance, as it is by these rules that the "par of exchange," or gold equivalent of the pound and dollar, is established at $4.866 = L i . In practice, payments in gold are comparatively rare. For one thing, certain countries prohibit the export of gold, and even in England small shipments are checked by the fact that the Bank of England will not sell gold in less quantities than 400 ounces. Also, payment in gold is a costly business. It has to be properly packed, shipped and insured against loss, and while it is on the ocean it is earning no interest. By the time an English debtor has paid in gold, he must deduct about 21 cents, representing the cost to him per pound's worth of gold shipped, from the dollar equivalent of $4.866 to Li, and so will only get about $4.841 for his pound. Conversely, the American shipper to England will also have to pay about 21 cents per pound, so that to the dollar cost to him of $4.866 for his pound's worth of gold he must add about 21 cents, making the total cost about $4.891. These rates of approximately $4.841 and $4.891 are called the "lower" and "upper gold points." It is not at first easy to see why in one case the cost is deducted, and in the other it is added. The best way to look at it is to remember that the result is always adverse to the shipper. The Englishman wants cheap dollars, but only gets $4.841 for his pound. The American wants cheap pounds, but has to pay $4.891 for each. This also explains why gold shipments are comparatively rare. In the vast majority of cases, the Englishman can buy more than $4.841 with his pound, and the American can buy his pound for less than $4.891. They do this as a rule through the medium of their banker, and so long as the rate of exchange remains between the gold points, they do not ship gold.

Methods of Making Foreign Payments.

Now to return to the table of supply and demand. Goods, as a rule, are bought and paid for with some form of bill of exchange (q.v.) . The bill is drawn in sterling or dollars by agreement between buyer and seller. Thus, the English buyer of American cotton might be drawn on in sterling, while the American buyer of Manchester goods might be drawn on in dollars. In a large number of cases the buyer might have a credit opened for him by his banker (see BILL OF EXCHANGE), and the seller would then draw his bill on the bank. In many other cases payment would be made by a cheque drawn by the buyer on his bank—just as if he were paying for his coals or his joint of meat—and sent direct to the seller. In a few cases the buyer might send actual currency notes, either pounds or dollars. Again, dividends on bearer stock are payable by the medium of coupons. These may be regarded as cheques to bearer drawn on the bank responsible for the service of the stock, and so come under the heading of bills of exchange. In many general cases the remitter of funds will buy, from his own bank, a draft drawn on a bank in the country to which he is remitting, and send this to the man to whom he owes the money.There is thus in constant circulation a huge mass of paper, bills, drafts, cheques, drawn in various currencies upon various in dividuals and banks, and it is the function of the foreign ex change market to provide a means for dealing with this mass. Until the present century, this was largely done direct. A large proportion of international trade was financed by bills drawn on London, the buyer, wherever he might be, getting a London house to accept on his behalf (see BILL OF EXCHANGE). Again, bills of all currencies and descriptions were either sold in the London market or sent to London for collection, with the result that London finance houses were continually in receipt of bills of all kinds. They, therefore, held the famous biweekly market "on change," in the Royal Exchange, and every house which had bills drawn in any currency to buy or sell would attend and get the best prices it could. These prices, of course, became the rates of exchange of the day.

The need for speed, and the development of the telephone, have put an end to dealings "on 'change," and the market now operates in different fashion. The best way to understand it is to revert to the relations between the trader and his bank. One or two examples may conveniently be cited. (For explanation of terms, see BILL OF EXCHANGE.) The Banks' Function.—The first is the simple one of an American selling cotton to an English merchant in Liverpool. The American draws on the Englishman in sterling at sight (D/P), and hands the bill and the documents to his New York bank for collection. The New York bank forwards these to the London bank which acts as its agent, and the London bank presents the bill to the Liverpool buyer, gets his acceptance and payment of the bill, then surrenders the documents. The cash so paid, it credits to the New York bank's account with it, and advises the New York bank, which promptly credits the seller's account with the dollar equivalent of the sterling sum. The important thing to note is that the New York bank's sterling balance in London has been increased.

The second example is that of a London investor receiving a dollar cheque drawn on a New York bank from a Wall street stock-broker who has sold stock in New York on behalf of his London client. The London investor either hands this cheque to his London bank for collection or else sells it to his London bank outright (save for the contingent liability attaching to his en dorsement). Whichever he does, the London bank forwards the cheque to its New York agent for collection, and the New York agent presents it, receives payment and credits the London bank's account with it with the proceeds. It then advises the London bank accordingly. If the London investor sold the cheque to his bank, he would be credited with the sterling equivalent there and then. If he handed it to the bank for collection, he would wait for his money until the London bank had been credited with it in New York. In either case, the London bank's dollar balance in New York has been increased.

In many instances, where a debtor has to meet a claim (includ ing a bill of exchange) expressed or drawn in a foreign currency, he buys a draft for the amount from his bank, drawn on his bank's account with its agent in the country concerned. Thus a London importer could meet a dollar bill drawn on him by a dollar draft drawn by his London bank on its New York agent. When an English traveller returned from New York hands dollar notes into his bank, the bank either keeps them against the needs of other customers who may be going to America, or else posts them to its New York agent for the credit of its dollar account.

One more difficult example may be cited. A German buys cotton from America, the terms of the deal being that the seller can draw in sterling on a London credit opened on behalf of the buyer. The buyer asks his German bank to arrange with its London agent to open the credit, and informs the seller accord ingly. The American seller then draws his bill on the London agent of the German bank, and either discounts it at his New York bank or tells his New York bank to collect it. In either case the New York bank forwards it to its own London agent, who presents it to the London agent of the German bank for ac ceptance, and in due course for payment. In this case there is a decrease in the sterling balance in London of the German bank and an increase in the sterling balance in London of the New York bank.

These examples show the foundation of modern foreign ex change dealings. This consists of the balances held by the banks of one country with the banks who act as their agents in foreign countries, such as the sterling balance in London of the New York bank, and the dollar balance in New York of the London bank.

Frequent mention has been made of the "equivalent rate," but before this can be explained, the operation of the foreign ex change market must be described. It will be realized that every one of the examples cited above ends in an increase or decrease in the balance held by one bank in one country with its agent in another. Were there a complete equilibrium every day in the supply and demand table previously given, these increases and de creases would obviously cancel out. As equilibrium never exists, some banks are always finding that their foreign balances are growing too big, while others find that they are becoming de pleted. They then have to buy and sell foreign currencies between themselves, and this is the modern foreign exchange market.

The London Foreign Exchange Market.

Every bank in London has a "dealer" whose job is to watch the size of his foreign balances and to buy or sell foreign exchange accordingly. There are also brokers in London who act as intermediaries be tween the dealers. One set of brokers will specialize in dollars, another in francs, and so on, so that a dealer wishing to buy and sell dollars knows that there are two or three special brokers whom alone he need approach. Each morning the broker rings up the various bank dealers and quotes the rate ; thus for dollars he might call "5 to 5k," meaning $4.85 to $4.8s4 to the pound. One dealer might want to buy $Io,000 to replenish his New York balance, and as he wants them as cheaply as he can get them, he might say he will "take at 54." Another dealer, with a surplus of dollars, may want to sell, but only "at 5." Then the broker tries to "get a fit," and in the middle of it some more buyers and sellers may come in at varying rates. If the broker has many buyers, he will call the rate to 5$," and so shake off some buyers and tempt out fresh sellers, for "4s to 5k" means, of course, dearer dollars than "5 to 51." So the day goes on, and every time the broker gets a buyer and seller to agree, he drops out at once, leaving them to put the transfer of dollars through between them. The only other thing he has to do is to collect his commission. The important thing is that normally he neither buys nor sells him self ; and the "double quotation" is not a buying and selling quota tion such as is made by a stock-jobber, but is made in that way for its psychological effect in tempting buyers and sellers to agree.The actual transfer of dollars is made by cables from the buying and selling banks in London to their agents in New York. By custom, two days after the deal, the one London bank pays the other London bank in sterling for the dollars, while the seller's dollar account in New York is debited and the buyer's credited, the dollars being paid over by the one New York agent to the other.

Rates of Exchange.

The rates at which these deals go through are called "cable rates," for the orders to the foreign agents for their execution are sent by cable. They cannot go be yond the gold points, for bankers would then find it cheaper to correct the size of their balances by an import or export of gold, bought in the one country and sold in the other. They are the rates published in the newspapers, and they are the basic rates for all exchange transactions and remittances made by banks for their customers, i.e., for the "equivalent rates" mentioned above. Some of these can now be described.(I) Cheque rate is the rate at which a bank will buy foreign currency cheques from its customers. If cable rate for dollars is $4.85, cheque rate would be slightly higher, say $4.85 s—z.e., the bank would insist on buying at a cheaper price or rate than the cable rate of the day. The reasons for this are (a) that the bank may want a small margin as an insurance against the risk of the cheque being a bad one; and (b) the bank pays sterling for the cheque at once, but does not receive the dollars until the cheque reaches New York and is presented for payment. Meanwhile, the bank is out of its money. When a dollar cheque is not sold, but is handed to the London bank for collection, the customer has to wait for his money until the cheque reaches New York and is paid. He gets his sterling at the cable rate ruling on the day the cheque is paid, less the charge made by his bank for collection.

(2) Sight rate is the rate at which a bank will buy foreign cur rency bills payable at sight. This is governed by the same con siderations as the cheque rate.

(3) Long rate is the rate at which a bank will buy foreign bills payable some definite period after sight (see BILL OF EXCHANGE). Here the bank is out of its money until such time as the bill matures, and the calculation of the rate is best illustrated by an example. Say the bill is for $100, has 90 days to run and the discount rate in America is 4% per annum ; then the buyer of the bill only gets $100 at the end of 90 days, which at 4% is the equivalent of $99.01 on the spot. If cable rate on the day of the purchase is $4.85, the sterling equivalent of $100 in three months is not f 10o=4.85, but f99.01=4.85, or f 2o.8s.3d., for $100 in three months is only worth $99.01 on the spot. The long rate can now be found by setting f 2o.8s.3d. against the original $zoo, and by simple division it comes out at about $4.89i. This round about way of calculation has been used to show exactly how and why the long rate is reached. The simpler and more usual method is to calculate directly from the cable rate, the equivalent interest being added thereto, as dollars in three months are cheaper than dollars on the spot. Were an American banker buying a three months' sterling bill, he would deduct the equivalent interest from the cable rate, making "long sterling" $4.84. This is because it is sterling that is cheaper, not dollars.

(4) Forward rates are the basis of a special market, which was built up to meet the difficulties arising from wild exchange fluctu ations prevalent from 1919-26. Just as a cotton spinner can buy or sell "futures," i.e., cotton for delivery on some fixed future date, so can a trader buy or sell foreign exchange from or to his bank for delivery one or two or three months ahead, at the for ward rate of the day on which he buys or sells. Once he has bought, say, forward francs at frs. 120 to the pound, he need not worry if, before he gets delivery and has to pay, the rate goes to 6o or 24o. Forward exchange has proved a very real protection to traders against exchange vagaries.

When a bank dealer is notified of a large sale (or purchase) of forward francs by his bank to a customer, he at once buys (or sells) in the market in equal quantities of spot francs. Then he is safe for the day against any big adverse jump in the spot rate, which would, of course, carry the forward rate with it. Just before the close of the day's business, he adjusts his open forward positions. To do this, he buys (or sells) such net amount of forward francs as he has over after taking into account all his bank's sales to and purchases from its customers, and at the same time "undoes" all his "guard" purchases and sales of spot francs by a net sale (or purchase) of spot francs at the closing cable rate of the day. He has thus balanced his forward book for the day.

Forward rates are always quoted in so-many centimes or cents above or below spot. If dealers are buying forward dollars, the forward rate may be a cent or so below spot, and vice versa. The reasons why a forward rate is sometimes above and at other times below the spot rate will be considered later. For the moment, all that need be done is to emphasize the fact that the considerations are totally different from those that govern long rate.

The Theory of the Foreign Exchanges.

It is now time to turn to more theoretical considerations. Why is it that there is a demand for sterling or francs or dollars? The answer is contained in four main rules. (I) Goods naturally flow to the market where prices are highest. (2) Investors turn to the market where they can get the highest and safest return on their money. (3) Bankers and financiers deposit their surplus funds in the centre where, granted adequate safety, they can obtain the highest interest. (4) If a country is losing gold, and/or finds trade and the stock ex change reaching a speculative height, and/or credit becoming "shaky," bankers in that country tend to raise interest rates.

Purchasing Power Parity.

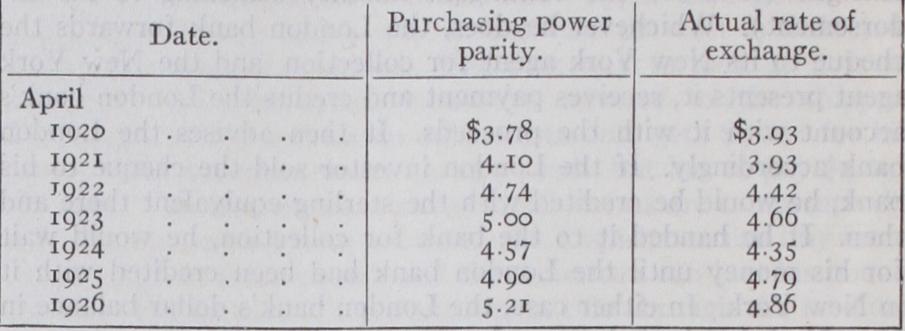

Rule (I) may be regarded as the basis of Professor Cassel's famous "purchasing power parity" theory. This is that if the shipment of gold is forbidden, so that the rates of exchange can move beyond the gold points, the rate of exchange between two countries is determined largely by the internal purchasing power of each country's currency. Thus in 1913, at par, £I =$4.866 and British and American internal prices each stood at Too (see INDEX NUMBERS). For the year 192o, British prices averaged 290 and American prices 23o, in round figures. According to the theory, it took L2.9 in 192o to buy the same as LI in 1913, and $2.3 to buy the same in 192o as $1 in 1913. Hence the 192o parity would not be £I=$4.866, but £2.9 = $4.866 X $2.3, or f I =$3.86. This theoretical rate of $3.86 Professor Cassel called the "purchasing power parity." So long as the actual rate was at that point, the British pur chaser would find British and American goods equally cheap, but if it moved, say to $3.96, American goods would be the cheaper, for he could then get more than a pound's worth of dollars for his pound. So he would buy American goods, and his banker would have to supply him with dollars out of his New York balance, so that he could pay for them. So his bank's dealer would start buying dollars, and force the rate lower till it reached $3.86, the point of equilibrium, when a pound would buy a pound's worth of dollars and no more. If the actual rate went, say to $3.76, the position would be reversed and Americans would start buying British goods.The theory holds in a different form when gold shipments are legal and the exchange is kept within the gold points. The English man and American alike buy in the cheapest market, and the country where prices are the higher begins to import goods. Pur chase of exchange to pay for them drives the rates down to the gold point, gold flows out and the loss of gold forces bankers to contract credit, call in loans and so make traders throw their stocks of goods on the market. This forces down prices at home to the point where home goods become cheaper than foreign, and so restores equilibrium. In the former case the rate is forced to conform to the purchasing power parity, but where the gold standard obtains, it is the purchasing power parity that is forced to conform to the rate.

The following table, dealing with England and the United States, illustrates the approximate character of the theory:— All than can be said is that the two move up and down together; in practice they rarely coincide. Of course, purchasing power parity can never be calculated exactly.

Rule (2), relating to stocks and shares, works out in a similar fashion. It is permissible to connect with this the high level of New York stock prices in the autumn of 1927, and the flow of American money to Europe for investment, which was one of the causes of the European exchanges being forced down to the gold point, so that gold was lost to Europe.

Exchanges, Discounts, Rates and Gold Shipments.—Rules (3) and (4) have been proved over and over again. A banker can obtain interest on his balances with his foreign agents at rates governed by the general level of interest rates in each country, and so, where interest rates rule high, he will let his balances grow, and even add to them by exchange purchases on his own account. For example, he may buy spot exchange and sell for ward exchange, and by so doing he will have foreign currency at his command for a definite period. Incidentally, this will make forward exchange cheaper than spot exchange, i.e., if London was buying spot francs and selling forward francs, the forward rate for francs would he above spot. The relative level of interest rates thus partly decides whether the forward rate is above or below spot. It follows from these rules that a rise in interest rates al ways checks an efflux of gold due to foreign exchanges reaching the gold point. A striking case of this occurred in London in the autumn of 1925. Many American bankers knew in 1924 that England was going back to gold, when the pound would be worth $4.866; so they bought pounds at $4.5, and $4.7, knowing they could eventually re-sell at $4.866. When these hopes were realized in April 1925, interest rates in London were high, so they left their money in London. In the early autumn of 1925 interest rates in London were lowered, and American bankers found their money could earn more at home. So back it came, and London lost millions in gold to New York. It was only when London rates were raised again that the loss of gold ceased.

In the autumn of 1927 London was again slightly above New York, and this time it was New York that lost gold. As a matter of fact, the three first rules united in making the exchanges unfavourable to the United States.

In short, adverse exchanges are a sign of (a) too high internal commodity and stock prices, and (b) too low internal interest rates. They lead to a loss of gold, and in self-protection bankers have to take steps which automatically correct these adverse factors. Equilibrium may take time to reach, but in the long run it is restored.

BIBLIOGRAPHY. Viscount Goschen, The Theory of the Foreign Bibliography. Viscount Goschen, The Theory of the Foreign Exchanges (186o) ; H. T. Easton, Money Exchanges and Banking (1907) ; H. Withers, Money Changing (1913) ; W. F. Spalding, Foreign Exchange and Foreign Bills (1925) ; A. C. Whitaker, Foreign Exchange (1919) ; T. E. Gregory, Foreign Exchange (1921) ; G. Cassel, Money and Foreign Exchange after i914 (1922) ; H. S. Jevons, Future of Exchange and the Indian Currency (1922) ; I. B. Cross, Domestic and Foreign Exchange, Theory and Practice (1923) ; G. W. Edwards, International Trade Finance (1924) ; A. W. Flux, The Foreign Exchanges (1924) ; H. F. R. Miller, The Foreign Exchange Markets (1925) ; Clare and Crump, Clare's A.B.C. of the Foreign Exchanges (1927) ; B. Nogaro, Modern Monetary Systems (1927). See also Proceedings of the Brussels Conference (1921) ; in vol. v. is included G. Cassel's "Memorandum on the World's Monetary Problems." (N. E. C.)