American Rugby

AMERICAN RUGBY This, as its name imports, is a derivative from the game invented and played at Rugby, in England, but passing through the rules of the Rugby Football Union. To understand properly its position relatively in the sports of America one must be slightly acquainted with the formative period in American football which preceded the adoption of the Rugby game.

Princeton and Rutgers, on Nov. 6, 1869, played the first inter collegiate football game in history, Rutgers winning by 6 goals to 4. The rules of the game were specially drafted, and followed generally the rules of the London Football Association, then as now, known as "Association" or "Soccer." Football at that time, as an organized sport, was not played at any of the other colleges in America. In 18 7o Columbia joined Princeton and Rutgers as an opponent. In 1872 came Yale, with a specially devised game of its own but based nevertheless on the Association code. In McGill university, of Canada, introduced Rugby to the United States by scheduling and playing, May 14, in that year, a game with Harvard which resulted in a draw, o to o. In the following year, Harvard invited Yale to play under the Rugby rules. Yale accepted but exacted certain concessions in the Rugby code from which the rules of the game as played were designated as the "Concessionary Rules." Princeton brought order out of chaos in 1876 by organizing an intercollegiate convention which was held at Springfield, Mass., on Nov. 23. This convention was attended by representatives of Columbia, Harvard, Princeton and Yale. The convention on that date organized the colleges represented into the American Intercollegiate Football Association. It adopted the rules of the Rugby Football Union of England as their common playing code ; and scheduled a mutual set of games.

The genius of young America for invention, however, appeared in that original convention and made one radical change in the English code. The Rugby players of England for many years had determined victory in their games by a majority of goals, the touchdown ("try") being only an incident in play which entitled a team to a try for a goal. The American collegians of 1876 modified this custom by changing Rule 8, in the code of that day, to read as follows: "A match shall be decided by a majority of touchdowns; a goal shall be equal to four touchdowns; but in case of a tie, a goal kicked from a touchdown shall take precedence over four touch downs." The adoption of this basic change in Rugby football started a movement in the American game that became one of the features of the sport, namely, the annual changing of the rules. In almost every year from 1876 through 1934, important changes were introduced.

On the whole the result of this vast body of changes has been to create a distinctive American game, featured by sustained, swift and intense action, skillful and varied performances, and by the brilliant, predominating characteristic of strategy and tactics.

This game has become the most popular of the collegiate sports. It has been adopted and is played by approximately 600 college teams and by about 3,00o school teams. The games of this great army of players annually attract approximately twenty million spectators. To accommodate this great and growing attendance the leaders in the sport have erected gigantic amphitheatres, stadia and bowls, seating from 2 5,00o to 1 oo,000. The annual income from this sport in a single university has exceeded $1,000,000 in one year. The game also is paying dividends to professional or ganizations and is being adopted by progressive cities as a part of their educational or playground systems.

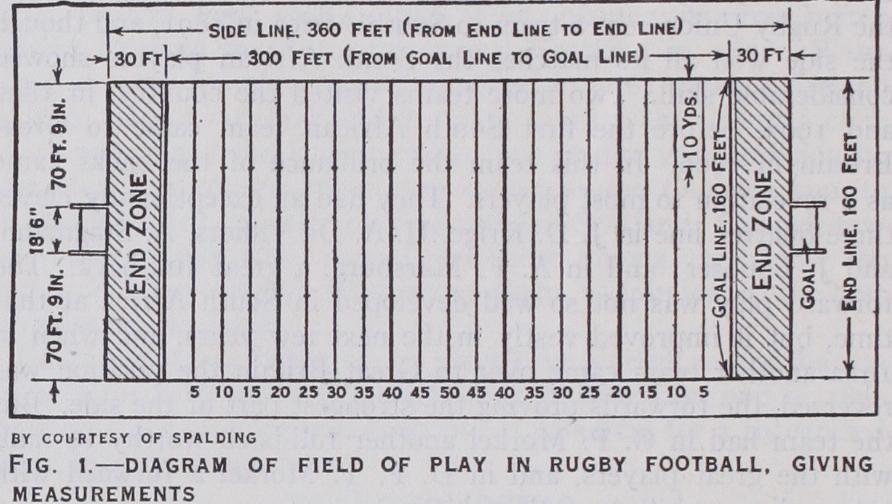

Playing Field.

The game is played upon a rectangular field, 36o ft. in length and 160 ft. in width. This field is marked with lines of lime. It is divided into sections known as the field of play and end zones. The field of play, 1 oo yd. in length, is divided into 20 spaces, each 5 yd. in width, also marked with heavy trans verse lines of lime, thus giving to the field of play a resemblance to a great gridiron, hence the origin of the grid-iron as a familiar name of the field. Each of the lines at 5-yard intervals is inter sected at right angles by short lines ten yards in from the side line on each side. At each end of the field is one of the end zones, 1 o yd. in length. The lines indicating the sides of this huge field are known as side lines. The lines at the end of the field of play are called goal lines, and the rear boundaries of the end zones are designated as end lines. In the centre of the end lines are erected goals. These consist of posts of wood or metal, exceeding 20 ft. in height, 18 ft. and 6 in. apart, connected by a cross bar the top of which is Io ft. above the ground. Directly in front of the goal posts at each end, a two-yard line is marked on the field of play.

Number of Players.

Eleven players constitute a side or team. This number is Etonian and not Rugbeian. It was copied from the Eton game and introduced into the American game in 1880. These players are divided into two sections, a line of seven men, known as the rush-line, or line of forwards and a group of four men known as the back-field or backs. The linemen and the positions which they occupy are named as follows: Left-end. Left tackle, Left-guard, Centre, Right-guard, Right-tackle and Right end. As arrayed on offence in the order named, they present technically a balanced line because in the arrangement three men are arrayed on each side of the centre as below.There are, however, many derivative line arrangements. When ever more than three players are arrayed on the same side of the centre, as in fig. 3, the alinement is known as unbalanced line.

The backs take their names from the positions they occupy in primary back-field grouping, namely, quarter-back, left half back, right half-back and full-back. When these backs are so arrayed that the quarter-back and the full-back are in a straight line behind the centre with a half-back on each side of the full back, they are said to be in a balanced formation (see fig. 2). When they are not thus evenly behind the centre they are said to be in an unbalanced formation (see fig. 3).

Objective.

The object of the game, concisely stated, for the offence, that is the side in possession of the ball, is to advance the ball, by a player carrying it forward in his arm, a method styled the running attack ; or by throwing the ball forward or laterally to be caught by a player of the same side, an advance known as a pass attack; or by kicking the ball forward, an assault styled the kicking attack. If the ball is carried across an opponent's goal line it constitutes a touchdown and counts 6 points. If it is thrown across and caught by a player of the same side it also is a touchdown and counts 6 points. The ball is kicked in three dif ferent technical ways. The first of these, the punt, is commonly employed to advance the ball. It is executed by dropping the ball from the hand and kicking it with the foot before the ball touches the ground. Such a kick cannot score unless the ball is fumbled or touched by a member of the receiving side and recovered over the goal line by one of the kicking side. Scoring by kicking, known as kicking a goal from the field, is accomplished by a drop kick or a place kick. A drop kick is a ball dropped from the hand or hands to the ground and kicked the instant it rises from the ground. A place kick is a ball kicked from a position of rest upon the ground. A goal from the field counts three points. A third method of scoring occurs when opponents are in possession of the ball so close to their own goal line that, to extricate themselves, the ball is sent across their own goal line and there touched down by one of them—a play known as a safety. This play credits two points to the score of their adver saries. A safety is scored any time the ball is declared dead on or over the goal line of the team defending it, provided the im petus which sent the ball over came, voluntarily or not, from the said team. The scoring of a touchdown not only counts 6 points but permits the scoring side to try for an additional score of one point. This they attempt to accomplish by putting the ball in play from scrimmage at any point on or outside the 2-yd. line and in a single play either carrying or passing the ball across their opponent's goal line or kicking a goal from the field. This manoeuvre is known technically as a try-for-point, or, popularly, as an extra point.The defence, that is the side not in possession of the ball, en deavours to prevent its opponents from carrying the ball forward by tackling the carrier. To make a tackle a player of the defence wraps his arm around the carrier and throws him to the ground. Similarly, the defence tries to prevent the ball from being passed forward or laterally and caught by the opponents by intercepting and catching the ball themselves, a performance technically known as an intercepted pass, or by batting or otherwise forcing the ball to the ground and recovering it if it has been passed laterally.

When the side in possession of the ball essays to kick it, the opponents endeavour to prevent the kick by blocking it, which is achieved by a player interposing his body against the ball while the latter is starting in flight. If the kick is blocked a great effort ensues by all the players of both sides to capture the ball. If, however, the kick is executed and the ball goes up the field the player of the receiving side attempts to catch the ball cleanly and run back up the field towards his opponent's goal.

Officials.

On account of the volume, variety and complexity of action in the American game an unusually large force of offi cials is required to conduct it. These consist of a referee, an umpire, a linesman and a field judge. The linesman also may select two assistant linesmen. The referee has general oversight and control of the game. He exercises a general supervision over the ball, is sole authority for the score and forfeiture of the game under the rules. He supervises the proper putting of the ball in play, its position and progress. The umpire is judge of the con duct and position of the players, and assists the referee in de cisions involving possession of the ball. The linesman, under the supervision of the referee, marks the distances gained or lost in the progress of play. His assistants operate on the side-lines two rods about 6 ft. in length connected at their lower ends by a stout cord or chain, ro yd. in length, for the purpose of marking conspicuously certain distances involved in play. The field judge acts as assistant to the other officials under the jurisdiction of the referee and supervises the time.The length of the game is 6o minutes divided into four playing periods of i 5 minutes each, exclusive of time taken out for delays. There is an intermission of one minute between the first and second periods; 15 minutes between the second and third; and one minute between the third and fourth. The higher score deter mines victory.

Kick-off.

The game opens with a formal play called the kick off (see Plate IV., fig. I). Prior thereto the referee calls the two opposing captains together and directs one of them to "call the toss" of a coin. If he wins the toss he has the choice of goals, or of kicking off, or of receiving the kick-off. The loser of the toss has the choice of the options which the winner does not select. These selections having been completed, the side in possession of the ball puts it down on its own 4o yd. line for the kick-off, and deploys along its 4o yd. line, as in fig. 4, for the purpose of running down the field under the kick, and keeping apace with the ball and preventing, if possible, its opponents from catching the ball and carrying it back. The side receiving the kick spreads over its territory (see fig. 5) so as to be able to make a clean catch of the ball, wherever it may come, and thereupon either to run it back or to kick it back. Experience and study have de signed a number of ingenious kick receiving formations. For the most common one see fig. 5.When the players of both sides are in position the referee blows his whistle to commence play. A player trained to kick off the ball kicks it high in the air up the field. The game is then in motion.

Orderly Possession of Ball.

The rules provide for the orderly possession of the ball by one side, with the right to put the ball in play, and barring a fumble, to execute the ensuing play. A fumble is the accidental dropping of the ball from the hands or arms of the carrier. A player of either side may recover and retain a fumbled ball. As the rules allow great freedom of action in the grouping of players in the methods of handling the ball, in advancing it, or of preventing an advance by opponents, there arises out of this rule relative to orderly possession another basic distinction of American Rugby, pre-arranged formations, tactics, plays and strategy. The right to put the ball in play by a team is designated as a down. Ordinarily a team upon obtaining the ball possesses the right to make four attempts to advance it a total distance of to yards. Each of these attempts constitutes a down. If in these four attempts or any part thereof this distance of io yd. is gained, the down instantly becomes a first down and the right is renewed to advance another io yd. in a similar series of four attempts. If in four consecutive downs a team fails to ad vance the ball io yd., the ball goes to opponents on the spot of the last down. The forward line is the line of scrimmage.

Offensive Formation.

An offensive formation is the tactical grouping of the players for the purpose of making an advance. Games frequently involve a series of preliminary formations. The basic formation of the offence is the balanced formation, as shown in fig. 2. From this formation every point of the defensive terrain may be attacked.In 1893 the tandem arrangement of the backs was invented, now called the unbalanced back-field formation. It was imposed, however, in 1893 behind a balanced line, as in fig. 6. This arrange ment was followed later by the introduction of the unbalanced line, thus giving to football its long-used formation of the un balanced backs behind the unbalanced line. (See fig. 3.) This formation commonly was made by arraying two of the backs in a tandem or straight line behind one of the tackles with the full-back about 4 yd. directly behind the centre and with the quarter-back kneeling or standing immediately behind the centre.

This formation generally known as the tandem formation fre quently was varied, as in fig. 7, by moving the quarter-back to the outside of the offensive end on the long side of the line, about i yd. behind the line.

From these two basic formations the football tacticians of America have evolved ingeniously many other offensive forma tions upon each of which they have erected elaborate systems of attacks technically known as plays. In one of these formations, now most frequently employed and known as the single wing, three of the backs are arrayed in a line oblique to the line of scrim mage, with the fourth back a yard outside of and behind an offen sive end. (See fig. 8.) In another formation (see fig. 9), like wise popular, and known as the double wing, a back is stationed I yd. outside and r yd. behind each one of the offensive ends, a third back behind one of the guards and the fourth back behind the centre, about 4 yd. from the line. The double wing is used with both a balanced and unbalanced line.

Another basic formation in the tactics of the game is the kick formation shown in fig. io, specially designed to protect the kicker and also highly useful as a basis for launching a varied attack. This formation is made by stationing the kicker, selected because of his kicking skill, about 8 to io yd. directly behind the centre with two backs in front of him on the side of his kicking foot, with the other back on the opposite side. Since this kick formation is highly adapted for the execution of a kick, a run or a pass, it is known as a triple threat formation. The player dropped back to kick, if also able to run or to pass, is known as a triple threat man. A variation of this formation used widely of late is the short kick, with the kicker 5 to 6 yds. back. There are many other arrangements of the backs designed for special as saults. Two of them are the spread and the line divide.

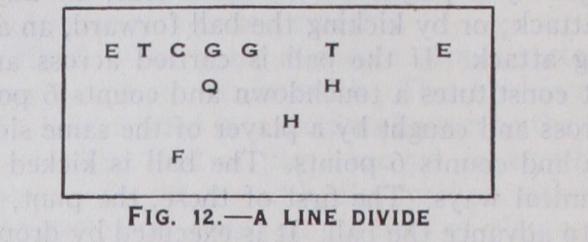

Preparatory to a spread play the line divides into two or more sections and deploys in as many groups widely across the field on the line of scrimmage. The backs also separate into two or more groups and likewise widely deploy across the field. The object of these tactics is to compel the defence also to spread widely and, therefore, to expose itself to an attack in an uncovered zone. As a spread formation is well suited for the launching of a run, a pass or a kick, the defence, if it concentrates to meet one of those forms of attack, exposes itself to an assault by means of one of the other two arms of offence. A second special offensive forma tion is the split line, shown in fig. 12, or as it is also called, the line divide. This in reality is a modified spread play. In it the line is divided by sending an end well out on the line of scrim mage, known as an End Out Formation, or by making a second wide space between the end and the tackle, known as a double divide. The object of the line divide or split line is to force the defence to spread to cover the points thus widely threatened.

The Forward Pass Attack.

The forward pass system of attack is a highly complicated and very ingeniously organized department of offensive play. On any play which starts with a scrimmage the offence is permitted to throw the ball forward provided the pass is made from a point 5 yd. behind the line. The pass may be caught only by players on the end of the line of scrimmage or who were i yd. behind the line when the ball was put in play. These are known as "eligible men." If one of these eligible men catches the pass, the pass is said to be a complete pass, and the receiver if not tackled may run for a farther advance. If the ball strikes the ground it is called an incomplete pass. Such a pass counts as a down but goes back to the point from which it was played. Any player of the defensive team may intercept in the air the forward pass of opponents by catching and retaining the ball. Upon such an interception the player who catches the ball may advance it toward his opponent's goal. A great many manoeuvres are designed for the purpose of executing forward passes. These manoeuvres involve feints and delays in order to delude the defence and to give the "eligible men" time to get down the field to receive the pass.

The Kicking Attack.

If a team fails to make the necessary gain of i o yd. in the four trials, or downs, it is required, as previ ously stated, to deliver the ball to the opponents on the spot of the last down. Customarily, a team perceiving that it will not make the io yd. in the four downs abandons the running at tack before these downs are exhausted and turns to a kicking attack, thus delivering the ball to the opponents at a greater dis tance from the former's goal-line, since a kick of the ball on the final down will send it ordinarily from 35 to 65 yd. deeper into the opponent's territory. If, however, the offence is within kick ing distance of the opponent's goal when it elects to kick it may not punt the ball but endeavour to score a goal from the field by kicking the ball, either by a drop kick or a place kick, over the opponent's cross bar.

Plays.

A "play" is any manoeuvre, either offensive or defen sive. On offence the plays are based upon the formations, that is to say, the team first assumes a tactical formation. From this formation a play may be launched or the team may shift into a secondary formation, to mislead the defence. General formations are so designed that various points not only may be attacked from one and the same formation but in order that these points may be attacked in different ways. These plays combine many movements on the part of the players, all of which are carefully worked out in detail by the coaches, rehearsed many times by the players and when finally perfected assigned a number by which they are known and controlled. Theoretically, in every play the i i players of the offence must be so disposed and utilized that each one of the II players of the defence will be prevented from stopping the attack. This involves charging the linemen back, making an opening in the line, boxing or pocketing the ends, blocking off the linemen and defensive backs, and in many other ways aiding the carrier of the ball. The men opening the way for the carrier separately are called "interferers," or "blockers," and, collectively, "the interference." Whenever an attack momentarily advances the ball the defence for that portion of time has been thus completely covered, and whenever a score is achieved it has been achieved because each player of the offensive side has discharged perfectly his assign ment or a member of the defence has failed to do his job. To aid in thwarting the defence many methods are employed. Plays are organized by concentrating the players of the offence so ingen iously and powerfully that the play moves forward by sheer might. These are known as power plays. Again, craft is employed to weaken the defence by feint movements in which a certain point is conspicuously threatened while the real attack strikes elsewhere. At times the interference goes in one direction and the carrier in another; at other times, the interference divides into two sec tions. These manoeuvres are known as split interference. Deliv ery of the ball is feinted, delayed and concealed to add to the confusion of the defence ; or the carrier on receiving the ball will hand it secretly to another player. All of these features are so well differentiated that they have come to be known technically by certain names. Plays usually take their popular names from the point and manner attacked. Thus the sport presents plays familiarly known as end runs, off-tackle slants, centre plunges, cross-bucks, line-bucks, concealed, delayed, double and triple passes, end-around, cut-backs, lobs, flat passes, man-in-motion, wasted man, pivots, whirls, race plays, reverses, lateral and mul tiple passes, splits, spreads, hidden ball and trick plays, spinners and quarter-back sneaks.While this list indicates the existence of a great many plays a team seldom carries more than 3o plays in its equipment, and many of these are duplicates, that is, the same play but designed to strike right or left in the same manner. Experience has proved that it is not a large variety of equipment that makes a team powerful but perfection of execution of an adequate number of plays.

The number of plays possible under any formation is limited only by the ingenuity of the generals of the game. To illustrate this distinctive and fascinating feature of American Rugby two plays will be selected as types and explained. The first of these, illustrated in fig. 13, is a reverse run wide around the oppo nent's short side right end on a spinner fake, such as Columbia University used to score against Stanford in the Rose Bowl. The quarter-back takes the pass from centre, spins around and fakes giving the ball to the right half who comes around to the left and runs close off his left end. The full-back drives straight across to the left and blocks the inrushing defensive right end. The left half comes around behind the spinning quarter-back, takes the ball and runs wide around the opponent's right flank.

The right guard comes out of the line to interfere and the left end and guard go down also to block defensive secondaries.

The centre, the two tackles and the right end check and the last three go down to cut off second aries coming across.

For a second illustration of a play a cross-buck will be selected and the balanced formation (see fig. 2) will be employed. The following is a diagram of the execution of this play : With the snap of the ball into action the offensive line charges sharply forward, the right-guard and right-tackle charging slightly obliquely as the opening is to be made between them. The quar ter-back and full-back leap with tremendous force against the point to be attacked, in order to aid in forcing the opening. The right-half simultaneously blocks off the defensive left-end. The left-tackle runs behind the opponents' line to cut down a secondary. The left-end does likewise, or as indicated in the diagram follows after the play to retrieve a fumbled ball. The ball in this play is passed directly to the left half-back who plunges across from left to right and strikes between his right-guard and right-tackle.

Defence.

The defensive systems in American Rugby are as highly involved but more standardized than those pertaining to the offence. The rules, by design, provide for a game in which the offence will have a slight preponderance of strength by making the zones of attacks, so far as rules are concerned, larger than the defence can cover. In other words, I i men are inadequate to cover their entire territory on defence. Some one spot must be exposed to attack. If the defence, however, is strong enough, swift enough and skillful enough, it can overcome this handi cap by mobilizing its players, or some of them, at the threat ened point. Therein largely originates the brilliance of de fensive football. Although the threat of the forward pass has largely caused it to be discarded in favour of the 6-man line, the basic principle of line defence is 7 men on the line to withstand the offensive assault of the 7 offensive forwards. The defensive players, however, are differently placed. Usually the centre and the two guards face their opponents. The defensive tackle plays slightly to the outside of his tackle. There are two systems of deploying an end on the defence. The most common one finds the end stationed about 4 yd. distant from his tackle. This is known as the wide-end defence. The other defence, known as the close-end defence, finds the end by the side of his tackle. The spaces of these defensive linemen vary on different teams according to the system employed. On some teams the spaces between the different players on the line are even, on the others the largest spaces are between tackle and end and the next larger between tackle and guard. The variation as to the ends on de fence not only covers their position but also extends to their use. Some systems require the end to charge through and plunge headlong into the adversary's interference for the purpose of breaking it up and forcing the runner into the open. This is called the smashing end defence. Other systems require the end to charge through but to hold the interference off with straight arms, thus remaining upon his feet but checking the interference and forcing the runner out. A third system requires the end to stand in his position on the line and wait until the interference comes to him. This is known as the waiting end defence. In this system the obligation is upon the tackle to get through and break the inter ference. Another variation in line defence is the use of the centre. In some junctures in the game described later under the title "Strategy," the centre plays in the line. For the most part, how ever, he drops behind the line as a support thus leaving only six men on the line.The use of the backs on defence presents a variety of systems. The most common of these formerly was the so-called "box de fence," in which 7 players stand upon the line, 2 backs known as tackle supports or wing backs each about 4 yds. behind his tackle, and the 2 remaining backs about 8 yd. behind them, the 4 backs thus forming a square or box as in fig. 15. This style of defence is the most powerful defence against a running attack, but is weak as a defence to forward passes and also ignores kicks entirely. As the rule regulating on side play prevents members of the kicking side who are in front of the ball when it is kicked from recovering it, automatically the ball when it comes to rest must go to the defensive team. The theory of the box defence, therefore, is that unable adequately to defend the entire field they take a chance on overhead forward passes and allow the kick of their opponents to go as far as it will. Other systems of defence, however, which endeavour to cover the entire field as far as possible, are formed as in fig. 16 by placing one of the backs in the deep back field to catch kicks, two about ten yd. behind the tackles as wing-backs and the fourth close up as a centre defence. This is known as the diamond or 7-1-2–I defence. When a centre is withdrawn from the line an opportunity for three differ ent defensive formations is possible ; one with 6 men on the line, 2 in a secondary line, 2 in the third line, with a fifth back in deep field to cover kicks and to tackle a runner who gets by the other lines of defence. (See fig. t 7.) The back in the deep back-field is called a safety man. Such a defence among football men is technically known as a "6-2-2-1 defence," and it is the one most widely used today.

If three backs are played in secondary line and two on the third line of defence, as in fig. i8, it is known as a "6-3-2 defence." and there is also the "6-2-3." Signal System.—An additional basic feature distinctive of American Rugby is the elaborate signal system by which its manoeuvres, formations, tactics and plays are controlled.

Coaching.

On account of the vast knowledge and the skill required to play the various positions in football as well as to amalgamate all of the players into a team functioning in unison with precision and accuracy, an elaborate system of coaching is required in the American Rugby game. Therefore, football estab lishments have a staff consisting of a head coach and assistant coaches. The assistant coaches are specialists, skilled in coaching certain positions or in coaching some special department of play or they may be skilled in strategy and tactics. These assistant coaches are assigned to their speciality by the head coach who is charged with the general preparation of the players and the team, and its supervision during a game.

Strategy,

or generalship, is the general policy of directing the play of a team. This depends upon many considerations. First of all it depends upon the detailed character of the play of op ponents as shown in previous games or as developed in the game being played. The first attacks directed against a team in a game are for the purpose of advancing the ball, of course, but they also are designed to find the strong and the weak spots in the de fensive establishment, either in their methods or in their in dividual players. The field general, usually the quarter-back, therefore, studies the system of lining up of his opponents. He notes the spaces between. the linemen, the distance from the tackles assumed by the ends, the position assumed by the tackles and the system of defensive play of the centre. Particularly he notes the disposition of the defensive backs, whether they are employing the box defence and thereby exposing their middle or deep back-field. He carefully watches the positions assumed by the wing-backs, and notes scrupulously the assumption by the de fence of a 7-2-2, a 7-1-2–I, a 6-3-2 or a 6-2-2-1 system.The general plan of conducting a game also requires taking advantage of the wind when this blows with substantial force directly or diagonally upon the back of a team. Such an aid brings into action frequently a vigorous kicking attack since the wind enables one back to out-kick the other and thereby gain ground without drawing upon the energies of the team for a running or passing attack until a striking position is achieved. Between his own 3o yd. line and the opponent's 3o yd. line, the strength of all points in the defensive line are tried out, and various general methods of attack are employed. Within this zone, it is orthodox to essay difficult and hazardous plays, criss crosses, triple passes, field reverses, forward passes, lateral passes and trick plays. If the field general finds he can advance, he se lects for use his long-gaining plays for the purpose of quickly approaching within scoring distance of his opponent's goal. If play forces a team behind its own 25 yd. line, the field general abandons the general attack unless his team is behind in the score. In this zone he often kicks on first down and seldom later than third down. No play involving the possible loss of the ball is prudently attempted within this zone. As the advance crosses the 25 yd. line the quarter-back changes his offensive policy. Here he employs a general attack. If he successfully leads his army across his opponent's 25 yd. line, he again changes his general plan of play. He calls for plays that he previously has found can make headway. As he crosses his adversary's io yd. line he should not employ plays which attack the centre of his adversary's line. The proximity of the goal-line behind his opponents has enabled them to abandon largely their back-field defence and bring up their backs to support the line and carefully to guard the centre.

If the offence is employing an unbalanced line and the defence does not re-aline or shift to match the distribution of strength, the quarter-back abandons an attack towards his short side. If, however, the defence re-alines or shifts so as to match man with man he will frequently send attacks on his weak side. If he sees that the defensive ends are playing wide from their tackles, he directs his plays inside the ends. When the ends move in to fill this gap the quarter-back changes his attack and out-flanks them. If the defensive centre is out of the line the attack is directed against the middle. With the centre behind the line, it is more difficult to complete a forward pass. With the centre in line and only 4 men left to cover the extensive back-field a for ward pass is in order. With the offence in the situation of a second or third down with only a yard to go, the defence is in a predicament. If the centre plays in the line he exposes his back field to a pass; if he plays behind his line he exposes the line to a running attack. Offensively, therefore, the quarter-back in such a juncture selects his play according to the position assumed by the defensive centre, who, however, may cross him by chang ing his position from the time the signal is given in the huddle until the ball is snapped.

The foregoing presentation of American Rugby constitutes a brief review of the basic structure of the sport, its tactics and strategy.