Battle of Falkland Islands

FALKLAND ISLANDS, BATTLE OF. One of the principal actions of the World War, known as the Battle of the Falklands, was f ought on Dec. 8, 1914, to the south-eastward of the Falkland Islands, between a British squadron under Vice Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee and a German squadron under Vice Admiral Graf von Spee. This battle was a counter-stroke to the battle of Coronel (q.v.).

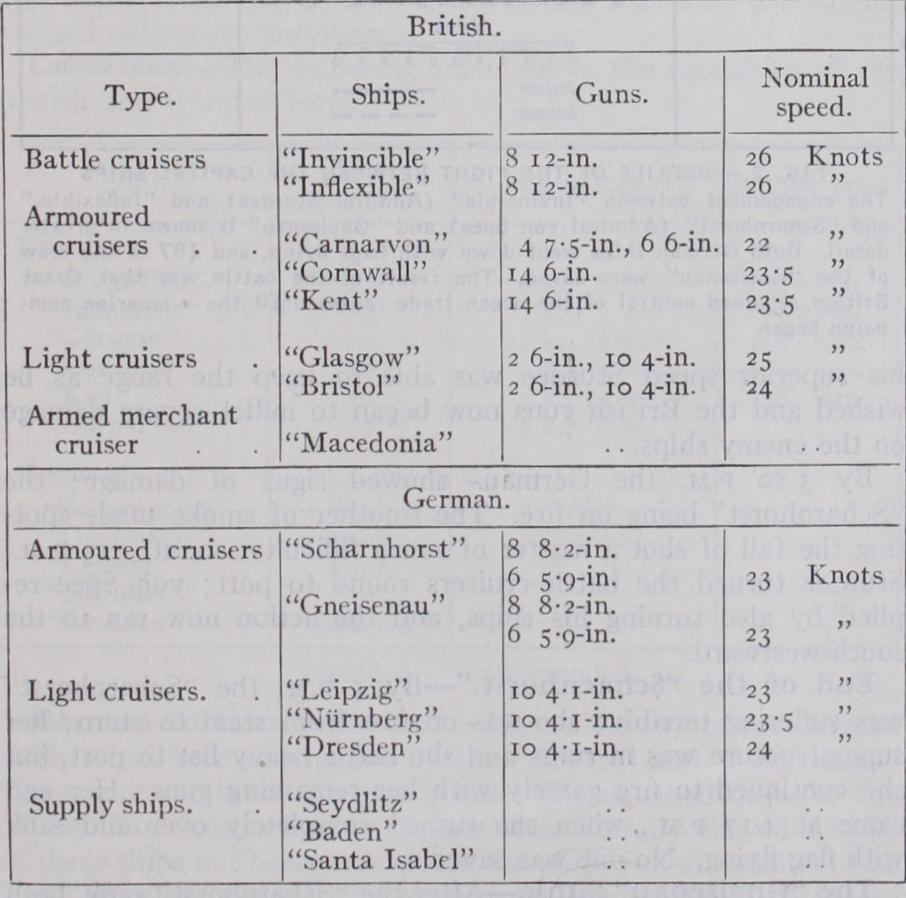

With the utmdst secrecy the two battle-cruisers "Invincible" and "Inflexible" had been detached from the Grand Fleet in the North Sea and sent, with all despatch, to reinforce the British squadron in the South Atlantic. Admiral Sturdee's orders, on leaving England in the "Invincible," were to "Seek out and destroy the enemy." The following table shows the details of the rival forces :— Fleet at Port William.—After the defeat of Admiral Cra dock's squadron at Coronel, the old battleship "Canopus" had returned to the Falklands and was berthed on the mud in Port Stanley, the inner harbour. Her light guns had been erected on shore and the entrance to the harbour mined with electric mines constructed out of old oil drums. A signal station had been erect ed and the local volunteers organized as a defence force. Thus being sturdily prepared for eventualities, the little colony had waited.

On his arrival at Port William on December 7, Admiral Sturdee ordered the "Macedonia" to patrol outside the harbour; the "In flexible" and "Kent" to be ready for 14 knots at half-an-hour's notice and the other ships of his squadron to keep steam for 12 knots at two hours' notice. Only three colliers were available, so all ships could not coal at once. By 6 A.M. on December 8, the "Carnarvon" and "Glasgow" had finished coaling. The "Invincible" and "Inflexible" then began. The "Bristol" had her fires out to remedy defects and the "Cornwall" had one engine opened up at six hours' notice; the "Glasgow" was also repairing machinery and could not be ready for two hours. Such was the situation when, at 7.5o A.M., the observation post on Sapper's Hill reported two strange ships in sight. At 7.56 A.M. the "Glasgow" fired a gun to draw attention to a signal flying in the "Canopus," making known this report.

German Squadron in Sight.

A scene of activity ensued; colliers were cast off and preparations made for leaving harbour. The "Kent," having just taken over guard duty, was ordered to weigh and observe the enemy. The general signal to weigh was made at 8.14 A.M. ; at 8.3o "Action" was sounded off and all ships were striving to raise steam at the earliest possible moment.

The two ships which had been sighted were the "Gneisenau" and "Nurnberg," which von Spee had sent on ahead to recon noitre; they were not visible from the "Canopus" but, with the aid of an extemporized observation hut which had been established on the hill, she opened fire on them at 9.15 A.M. with her i 2in. guns. The range, however, was too great and the shots fell short ; nevertheless, the firing made the two German ships turn away to the south-east.

Von Spee, in the "Scharnhorst" was some 15 miles distant from the harbour, but the clouds of smoke visible over the intervening land made him suspicious. The "Gneisenau" was near enough to make out the masts and funnels of six ships in the harbour, and, worse still, some observers thought they could distinguish the tripod masts of battle-cruisers. The report from the "Gneisenau" confirmed von Spee in his misgivings and he immedi ately ordered the advanced ships not to accept action. This order was followed by a general signal to his squadron to raise steam in all boilers and steer east.

Von Spee's Intentions.—It is impossible to be sure with what intention Admiral von Spee made for the Falkland Islands. By one account he expected to find there a British squadron weaker than his own; he hoped to draw them to sea, destroy them, and then occupy the Islands. Some colour is lent to this by the re port of British officers at the observation post on shore that they could distinguish, through telescopes, men on board the "Gneisen au" dressed and equipped ready for landing. Von Spee was certainly unaware that the Admiralty had despatched two battle cruisers to these waters. Their arrival just in time was a stroke of luck which the latter fully deserved ; but Admiral Sturdee was momentarily at a distinct disadvantage owing to his ships being at anchor with colliers alongside.

Von Spee's position if the British squadron brought him to action in the open was hopeless ; but if the Germans had pressed home an attack at the entrance to the harbour, the prospects would have been far from pleasant for the British forces within.

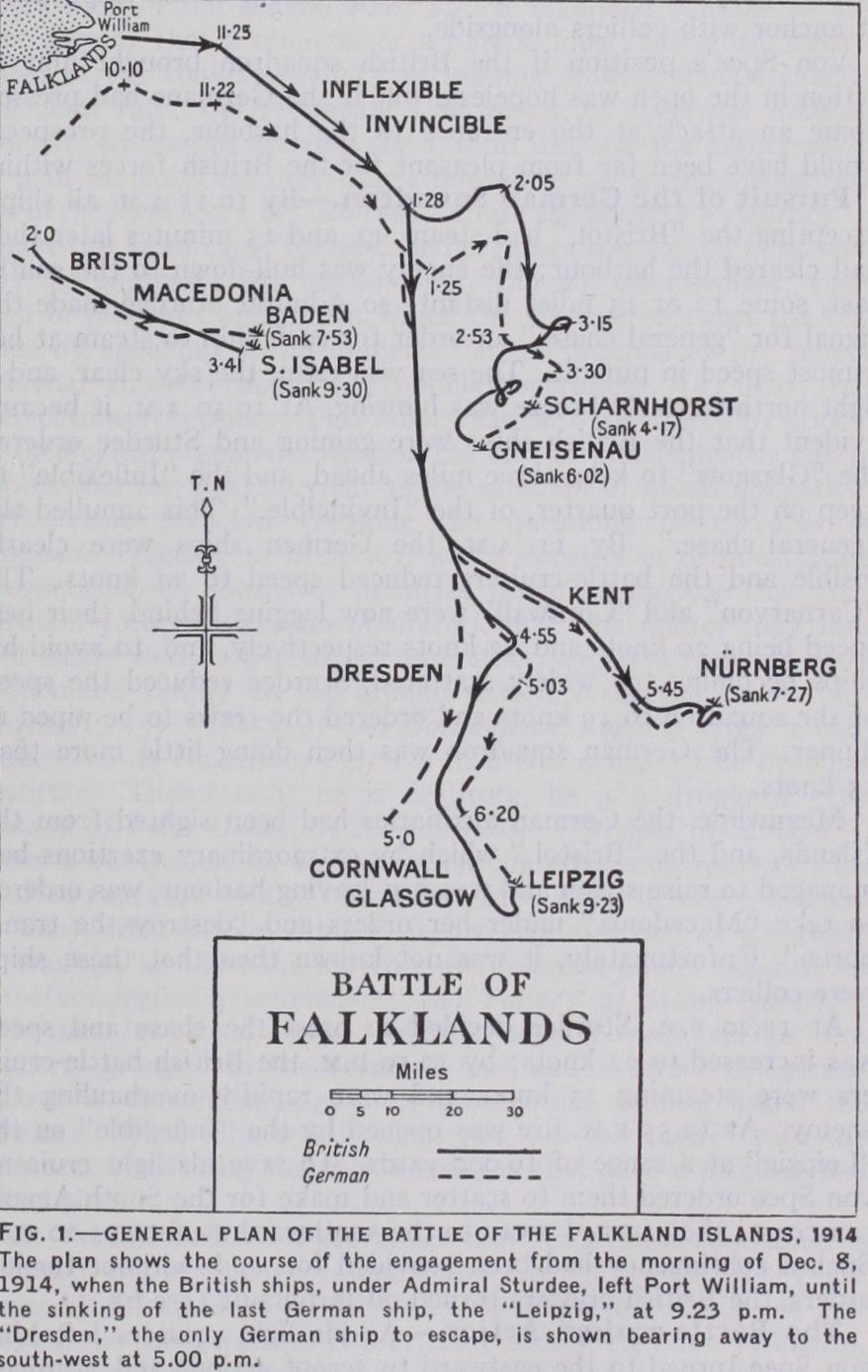

Pursuit of the German Squadron.—By 10.15 A.M. all ships, excepting the "Bristol," had steam up, and 15 minutes later they had cleared the harbour ; the enemy was hull-down to the south east, some 12 or 13 miles distant; so Admiral Sturdee made the signal for "general chase," an order for each ship to steam at her utmost speed in pursuit. The sea was calm, the sky clear, and a light north-westerly breeze was blowing. At 10.50 A.M. it became evident that the British ships were gaining and Sturdee ordered the "Glasgow" to keep three miles ahead, and the "Inflexible" to keep on the port quarter, of the "Invincible." This annulled the "general chase." By II A.M. the German ships were clearly visible and the battle-cruisers reduced speed to 24 knots. The "Carnarvon" and "Cornwall" were now lagging behind, their best speed being 20 knots and 2 2 knots respectively, and, to avoid his ships becoming too widely scattered, Sturdee reduced the speed of the squadron to 19 knots and ordered the crews to be piped to dinner. The German squadron was then doing little more than 15 knots.

Meanwhile, the German auxiliaries had been sighted from the Islands, and the "Bristol," which by extraordinary exertions had managed to raise steam and was just leaving harbour, was ordered to take "Macedonia" under her orders and "destroy the trans ports." Unfortunately, it was not known then that these ships were colliers.

At

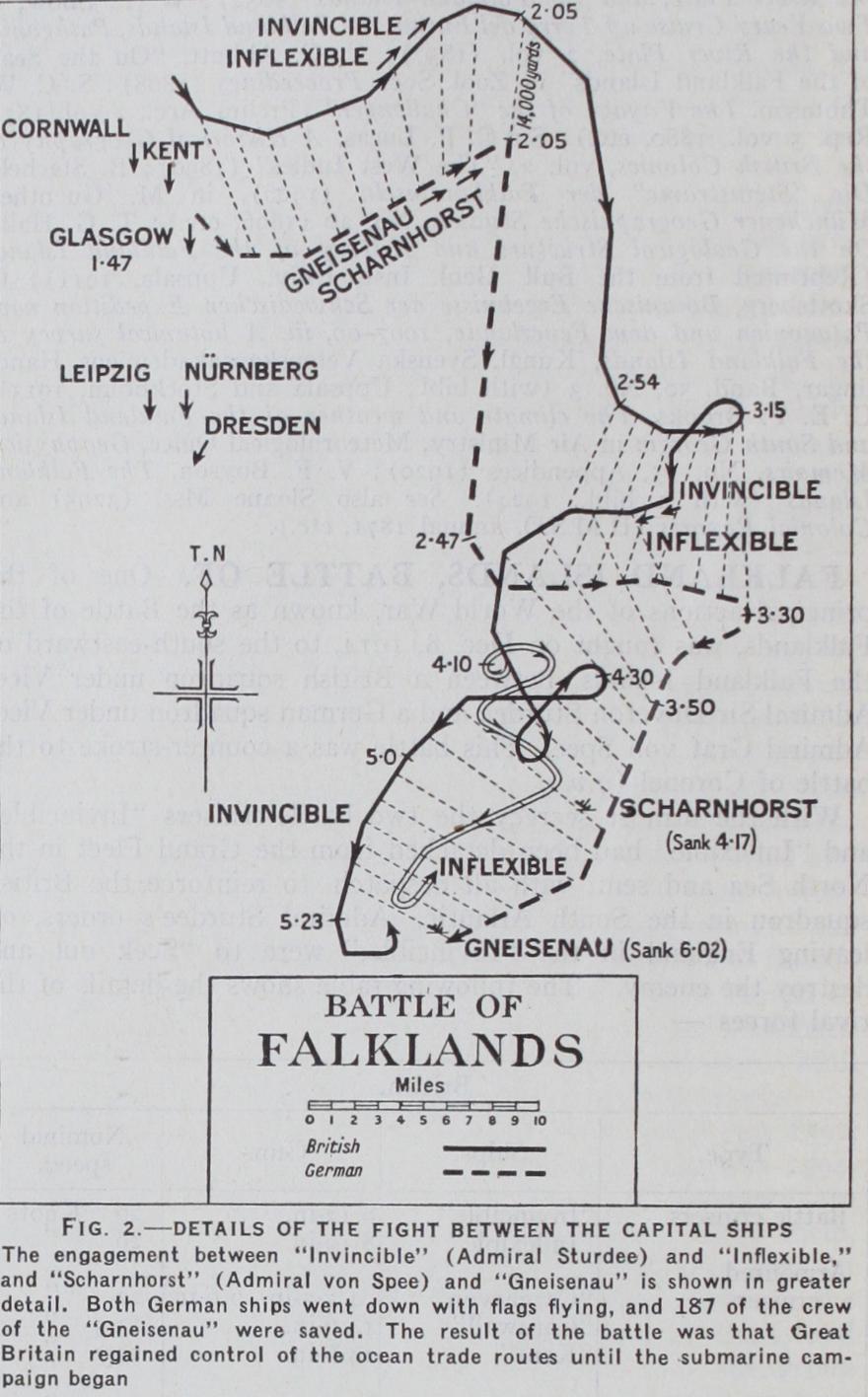

12.20 P.M. Sturdee decided to press the chase and speed was increased to 22 knots; by 12.5o P.M. the British battle-cruis ers were steaming 25 knots and were rapidly overhauling the enemy. At 12.55 P.M. fire was opened by the "Inflexible" on the "Leipzig" at a range of 16,000 yards. To save his light cruisers, von Spee ordered them to scatter and make for the South Ameri can coast; they turned away to the southward at about 1.20 P.M. Such a contingency had been provided for, and, without further orders, the British cruisers turned off in pursuit (see fig. I) .The Battle-cruiser Action.—As his light cruisers left him, von Spee turned to the eastward to accept action; and Sturdee's battle-cruisers turned into line ahead on a nearly parallel course to the enemy. Fire was now opened on both sides, but the range —about 14,000yd.—was too great, and the shots from the Ger man ships fell short. The range closed to 12,5ooyd. and about 1.45 P.M. "Invincible" was hit; whereupon Sturdee turned away to open the range and obtain full advantage from his heavier armament. His object was to annihilate the enemy, but in doing so to receive as little damage as possible. By 2 P.M. the range had increased to i6,000yd. and firing ceased for a time (see fig. 2) .

In order to renew the action, the British battle-cruisers altered course to starboard, and gradually reduced the range to 15,000yd. Fire was then reopened and von Spee again accepted action, manoeuvring his ships to reduce the range sufficiently for his secondary armament to be brought into action. Sturdee allowed the range to fall to about 12,5ooyd. and then, as the Germans began to fire with their 5.9-in. guns, he sheered off again. With his superior speed Sturdee was able to keep the range as he wished and the British guns now began to inflict severe damage on the enemy ships.

By 3.10 P.M. the Germans showed signs of damage ; the "Scharnhorst" being on fire. The smother of smoke made spot ting the fall of shot a matter of some difficulty, so, at 3.15 P.M., Sturdee turned the battle-cruisers round to port ; von Spee re plied by also turning his ships, and the action now ran to the south-westward.

End of the "Scharnhorst."—By 4 P.M. the "Scharnhorst" was suffering terribly ; she was on fire from stem to stern ; her superstructure was in ruins and she had a heavy list to port, but she continued to fire gamely with her remaining guns. Her end came at 4.17 P.M., when she turned completely over and sank with flag flying. No one was saved.

The "Gneisenau" Sunk.—Af ter the "Scharnhorst" sank, both battle-cruisers engaged the "Gneisenau," and, to prevent being blinded by smoke, steered on independent courses. The "Carnar von" had now been able to close sufficiently to open fire, and the doomed German cruiser became a target for a concentrated fire from three directions. Her fire slackened ; she was on fire fore and aft and her speed rapidly dropped. Her one remaining gun continued to fire at intervals; but at 5.4o P.M. her splendid fight against hopeless odds was at an end and she heeled slowly over and sank at about 6 P.M. The British ships closed, lowered their boats and succeeded in rescuing 187 survivors from the icy water. The Light Cruisers.—When the German light cruisers broke away, they had about II miles' start on their pursuers. The British ships had nominally no superiority in speed, but, owing to their recent continuous cruising, the boilers in the German ships were in no condition to withstand severe pressure. At first the enemy kept together (see fig. I). The "Glasgow" was the fast est of the pursuers and soon forged ahead of her consorts, the "Kent" and "Cornwall," and, having crossed ahead of them, she headed for the "Dresden," the fastest of the pursued. It was, however, soon evident that the only chance of bringing the enemy to action before the light failed, was to attack the rearmost ship, in the hopes that this would bring the others back to her assist ance.

"Glasgow" and "Cornwall" versus "Leipzig."—At P.M. the "Glasgow" opened fire on the "Leipzig" and by 4.15 P.M. the "Cornwall" had closed the range sufficiently to bring her guns into action. The "Leipzig" suffered considerably under the cross-fire from the two British cruisers; her speed too was fall ing so rapidly that her attackers were in the fortunate position of being able to keep the range as they desired. By 7 P.M. the "Leipzig's" stern was enveloped in flames and she was in sorry plight, but she made no sign of surrender. At about 8.10 P.M. she made signals of distress and the British ships closed and lowered boats to rescue survivors. At 9.23 P.M. there was an explosion and the "Leipzig" disappeared.

"Kent" versus "Nurnberg."—The "Kent" meanwhile had been pursuing the "Nurnberg" and, by extraordinary efforts on the part of her engine-room department, succeeded in exceeding her designed speed. At 5 P.M. the "Nurnberg" opened fire, but the 6-in. guns of the "Kent" were not yet within range. The weather was becoming thick, owing to a fine drizzle having set in, when fortune favoured the pursuer ; the "Nurnberg's" boiler tubes gave out and her speed sank rapidly, which enabled the "Kent" to close to effective range. By 6.25 P.M. the "Nurnberg" was a blazing wreck and about 7.3o P.M. she turned over and sank. The boats from the "Kent" searched the sea until 9 P.M. but rescued only seven survivors.

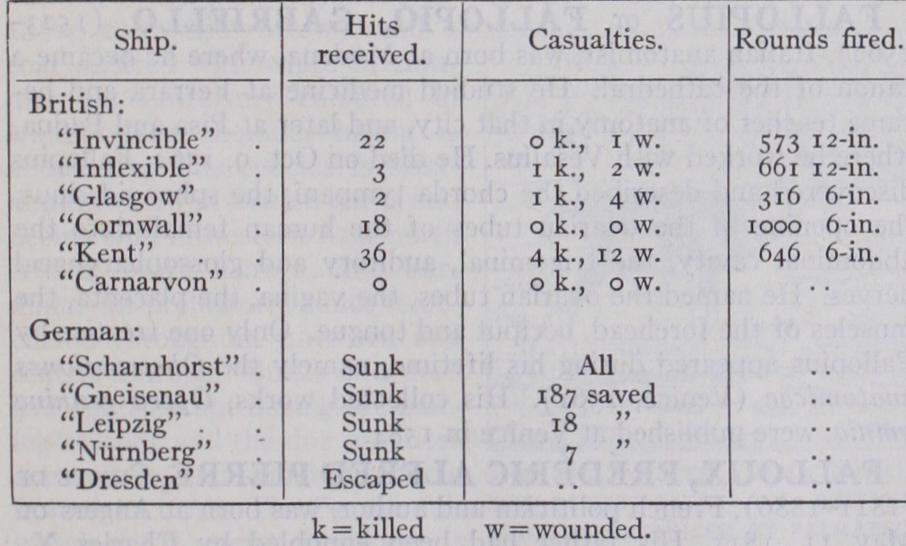

Casualties.—The following table shows the casualties of the British and German forces:— German Colliers Destroyed.—Meanwhile two of the German colliers had been overhauled by the "Bristol" and "Macedonia." They were captured at about 4 P.M. The signalled order to the "Bristol" to "destroy the transports" was literally obeyed in spite of these ships not being transports, but ships full of valuable coal. The "Dresden" escaped and was not hunted down and destroyed until March 14, 1915.

Conclusion.—The Battle of the Falklands was a very decisive victory for the British, inasmuch as it marked the end of a definite phase of the war at sea. As a result, German cruiser war fare collapsed and England held, outside the narrow seas, undis puted control of the ocean trade routes of the world.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-H. E. H.

Spencer Cooper, The Battle of the FalkBibliography.-H. E. H. Spencer Cooper, The Battle of the Falk- lands (1919) ; R. H. C. Verner, The Battle-Cruisers at the Action of the Falkland Islands (1920) ; J. S. Corbett, History of the Great War, Naval Operations, vol. i. (1921) ; The Hon. Barry Bingham, Falk lands, Jutland and The Bight; Germany Marine Archiv., Krieg zur See; Kreuzerkrieg, vol. i. (1924). See also WORLD WAR: BIBLIOGRAPHY.