Falconry

FALCONRY. The art of employing falcons and hawks in the chase, often termed hawking (Fr. fauconnerie, from late Lat. falco, falcon). Falconry was a favourite recreation of the aristocracy during the middle ages, followed, as it seems, more as a sport than as a means of getting game for the table. The antiquity of falconry is very great. It appears to have been known in China some 2,000 years B.C. In Japan it appears to have been known at least 600 years B.C., and probably at an equally early date in India, Arabia, Persia and Syria. Sir A. H. Layard says that on a bas relief found in the ruins of Khorsabad "there appeared to be a falconer bearing a hawk on his wrist," from which it would appear to have been known there some 1,70o years B.C. In all the above mentioned countries of Asia it is practised at the present day.

Persian and Arabic manuscripts attribute the origin of falconry to a pre-historic Persian king; certain it is that the Moguls gave a great impetus to hawking in India. From ancient carvings and drawings it seems to have been known in Egypt many ages ago. The older writers on falconry, English and Continental, of ten mention Barbary and Tunisian falcons. It is still practised in Egypt. The oldest records of falconry in Europe are in the writ ings of Pliny, Aristotle and Martial. It was probably introduced into England from the Continent about A.D. 86o, and from that time down to the middle of the 17 th century, falconry was fol lowed with an ardour that perhaps no English sport has ever evoked. Stringent laws and enactments were passed from time to time in its interest. About the middle of the I 7 th century its popularity began to decline in England, to revive somewhat at the Restoration; it never however recovered its former favour, a variety of causes operating against it, such as the enclosure of waste lands and the introduction of fire-arms into the sporting field. Yet it has never been even temporarily extinct, and it is practised at the present day.

In Europe the "quarry" at which hawks are flown consists of grouse (confined to the British Isles), black-game, pheasants, partridges, quails, landrails, ducks, teal, woodcocks, snipe, herons, rooks, crows, gulls, magpies, jays, blackbirds, thrushes, larks, hares and rabbits; in former days geese, cranes, kites, ravens and bustards were also flown at. Old German works make much mention of the use of the Iceland falcon for taking the great bus tard, a flight scarcely alluded to by English writers. In Asia the list of "quarry" is longer, and in addition to all the foregoing, or their Asiatic representatives, various kinds of bustards, sand grouse, storks, ibises, spoonbills, stone plovers, grass owls, short eared owls, rollers, hoopoes, pea fowl, jungle fowl, kites, vultures and gazelles are captured by trained hawks. In Mongolia and Chinese Tartary, and among the nomad tribes of Central Asia the sport still flourishes ; and a species of eagle known locally as the "berkute" is trained in those regions to take large game, such as antelopes and wolves. In a letter from the Yarkand embassy, dated Nov. 27, 1873, the following passage occurs: "Hawking appears to be a favourite amusement, the golden eagle taking the place of the falcon or hawk." In Africa gazelles are taken and also partridges and wild fowl. The hawks used in England are the Greenland, Iceland and Norway falcons, the peregrine falcon, the hobby, the merlin, the goshawk and the sparrow-hawk. In former days the Baker, the Tanner and the Barbary or Tunisian falcon were also employed. The most efficient in the field are the peregrine falcon and the goshawk. In all species of hawk the female is larger and more powerful than the male.

Hawks are divided by falconers all over the world into two classes. The first class comprises "falcons," i.e., "long winged hawks," or "hawks of the lure." Merlins come into this category; they are undoubtedly falcons. The goshawk was by courtesy sometimes styled a falcon. The second class is that of "hawks," i.e., "short-winged hawks," or "hawks of the fist"; in these the wings are not pointed but rounded.

is through the appetite principally that hawks are tamed; but to fit them for use in the field, much patience. gentleness and care are necessary. Slovenly taming necessitates starving, and low condition and weakness are the result. The aim of the falconer should be to have his hawk always keen, and the appetite, when it is brought into the field, should be such as would induce the bird in a state of nature to put forth its full powers to obtain its food, with, as near as possible, a corresponding bodily condition.

The following is a description of the process of training hawks. When first taken, a ruf ter or easy-fitting hood should be put on her head, and she must be furnished with jesses, swivel, leash and bell; jesses are strips of light leather for the legs. A thick glove or rather gauntlet should be worn on the left hand. (Eastern falconers always carry a hawk on the right.) She must be carried on the fist for several hours at a time, and late into the night, at intervals being gently stroked with a bird's wing or feather. At night she should be tied to a perch in a room with the windows darkened, so that no light can enter in the morning. The perch should be a padded one placed across the room about 41f t. from the ground with a canvas screen underneath. She will be easily induced to feed, in most cases, by drawing a piece of beef-steak over her feet, brushing her legs at the time with a feather, and now and then, as she snaps at it, slipping a morsel into her mouth. Care must be taken to use a low whistle as she is in the act of swallowing; she will very soon learn to associate this sound with feeding, and it will be found that directly she hears it, she will gripe with her talons and bend down to feel for her food. When the falconer perceives this and other signs of her "coming to," that she no longer starts at the voice or touch, and steps quietly up from the perch when the hand is placed under her feet, it will be time to change her rufter hood for the ordinary hood. This latter should be an easy fitting one, in which the braces draw closely and yet easily, and without jerking. An old one previously worn is to be recommended. The hawk should be taken into an absolutely dark room, and the change should be made if possible in total darkness. After this she must be brought to feed with her hood off ; at first she must be fed in a darkened room, more light being admitted as she is able to bear it. The first day, the hawk having seized the food, and begun to pull at it freely, the hood may be gently slipped off, and after she has eaten a moderate quantity, it must be replaced as slowly and gently as possible, and she should be allowed to finish her meal through the hood. Next day the hood may be twice removed, and so on; day by day the practice should be continued, more light being gradually admitted, until the hawk will feed freely in broad day light, and suffer the hood to be taken off and replaced without opposition. She must now be accustomed to see strangers, dogs, horses, etc., and to feed in their presence. A good plan is to take her into the streets of a town at night, at first where the gas-light is not strong, unhooding and hooding her from time to time, but not letting her get frightened. Up to this time she should be fed on lean beef-steak with no casting, but as soon as she is tolerably tame and submits well to the hood, she must occasionally be fed with pigeons and other birds. This should be done not later than 3 or 4 P.M., and when she is placed on her perch for the night in the dark room, she must be unhooded and left so, of course, being carefully tied up. The falconer should enter the room about 7 or 8 A.M. next day, admitting as little light as possible, or using a candle. He should first observe if she has thrown her casting; if so, he will at once take her to the fist, giving her a bite of food and rehooding her. If her casting has not been thrown up it is better for him to retire, leaving the room quite dark, and come in again later. He should leave her unhooded until such time as she has "cast." She must now be taught to recognize the voice—the shout that is used to call her in the field—and to jump to the fist for food, the voice being used every time she is fed. When she comes freely to the fist she must be made acquainted with the lure. Kneeling down with the hawk on his fist, and gently unhooding her, the falconer casts out the lure, which may be either a dead pigeon, or an artificial lure garnished with beef-steak tied to a string, to a distance of a few feet in front of her. When she jumps down to it, she should be allowed to feed a little upon it— the voice being used—while occasionally receiving morsels from the falconer's hand ; and before her meal is finished she must be taken up on to the hand, being induced to forsake the lure for the hand by offering her a piece of meat. This treatment will help to check her inclination hereafter to carry her quarry. This lesson is to be continued till the falcon feeds boldly on the lure on the ground in the falconer's presence—till she will allow him to walk round her while she is feeding. All this time she will have been held by the leash only, but in the next step a strong, but light creance—a line attached to the swivel—must be made fast to the leash, and an assistant holding the hawk should unhood her, as the falconer, standing at a little distance from her, calls her by shouting and casting out the lure.

Day by day the distance will be increased, until the hawk will come 3o, 6o, iooyds. and so on without hesitation : then she may be trusted to fly to the lure at liberty and by degrees from any distance, say zoo yards. This accomplished she should learn to stoop at the lure. Instead of allowing the hawk to seize upon it as she comes up the falconer will snatch the lure away and let her pass by, and immediately put it out that she may readily seize it when she turns round to look for it. This should be done at first only once, and then progressively, until she will stoop backwards and forwards at the lure as often as desired: Next she should be entered to her quarry. Should she be intended for rooks or herons, two or three of these birds must be procured. One should be given her from the hand, the next released close to her, and the third at a considerable distance. If she takes these keenly she may be flown at a wild bird, care must, how ever, 'be taken to let her have every possible advantage in her first flights—wind and weather, and the position of the quarry with regard to the surrounding country being an important con sideration.

Eyasses, on being received by the falconer before they can fly must be put into a sheltered place, such as an outhouse or shed. The basket or hamper should be filled with straw. A hamper is best, with the lid so placed as to form a platform upon which the young hawks can come out to feed. This should be fastened to a beam or prop a few feet from the ground. The young hawks must be plentifully fed on the best fresh food ob tainable—such as good lean beef and fresh killed birds and rab bits. The food should be securely tied in separate portions to a board, or better to wooden blocks, one for each hawk. At this stage the young hawk should be interfered with as little as pos sible. The falconer should place the food down for them and then retire as quickly as possible. The wilder and more inde pendent they become during the period of "hack" the better. As they grow older they will come out and perch about the roof of their shed, by degrees extending their flights to neighbouring buildings or trees, never failing to come back at feeding time to the place where they are fed. Soon they will be continually on the wing, soaring up and playing with one another, and later the falconer will observe them chasing other birds, such as pigeons or rooks, which may be passing by. As soon as a young hawk fails to return to the hack for its meal a note should be made of its absence, and it should at once be caught in a bow net or snare the first time it comes back, or it may absent itself for good. It must be borne in mind that the longer hawks can be left out "at hack" the better they are likely to be in the field—those hawks being always the best which have preyed a few times for them selves when "at hack." There is, of course, a great risk of losing hawks altogether when they begin to prey for themselves, but this is a matter for the falconer's judgment. When a hawk is so caught she is said to be "taken up" from hack. Being an eyas, she will not require a rufter hood, but a good deal of the man agement as directed for the passage falcon will be necessary in her case also. She must be carefully tamed and broken to the hood in the same manner, and also taught to know the lure ; but, as might be expected, very much less difficulty will be experienced. As soon as the eyas knows the lure sufficiently well to come to it sharp and straight from a distance, she must be taught to "wait on." This is effected by letting the hawk loose, choosing the most open space available. It will be found that she will circle round the falconer looking expectantly for the lure—perhaps mount a little in the air, and advantage must be taken of a favourable moment when the hawk is at a little height, her head being turned inwards towards the falconer, to loose a pigeon with shortened wings which she can easily catch. When the hawk has taken two or three pigeons in this way, and mounts into the air immediately in expectation, in short, begins to "wait on," she should be given no more pigeons, but be tried at game as soon as possible. The young hawk must be given every possible advantage when first flown at wild quarry, as, upon the success or failure of these early attempts, her subsequent career of usefulness chiefly de pends.

The training of the great northern falcons, as well as that of merlins and hobbies, is conducted much on the above principles, but the jer-falcons will seldom "wait on" well, and merlins will not do so at all.

The training of short-winged hawks is a simpler process. They must, like falcons, be provided with jesses, swivel, leash and bell. In these hawks the bell is sometimes fastened to the tail. Sparrow-hawks can, however, scarcely carry a bell big enough to be of any service. The hood is seldom used for short-winged hawks—never in the field. They must be made as tame as pos sible by carriage on the fist and the society of man, and taught to come to the fist freely when required—at first to jump to it in a room, and then out of doors. When the goshawk comes freely and without hesitation from short distances, she would be called from longer distances from the hand of an assistant, but not oftener than twice in each meal, until she will come several hun dred yards, on each occasion being well rewarded with some favourite food such as fresh killed birds. When she does this freely, and endures the presence of strangers, dogs, etc., a few bagged rabbits may be given to her, and she will be ready to take the field. Some accustom the goshawk to the use of the lure, for the purpose of recovering her if she refuses to come to the fist in the field, when she has taken stand in a tree after being baulked of her quarry, but this is not a good practice.

Methods of Hawking.

Falcons or long-winged hawks are either "flown out of the hood" (i.e., unhooded and slipped when the quarry is in sight), or they are made to "wait on" till game is flushed. Herons and rooks are always taken by the former method. Passage hawks are generally employed for flying at these birds, though good eyasses are occasionally equal to the work.For heron hawking a well stocked heronry is essential, adjoin ing an open country (with no adjacent water) over which the herons are in the constant habit of passing on their fishing ex cursions, or making their "passage." A heron found at his feed ing place at a brook or pond affords no sport whatever. A gos hawk can then take him as he rises, before he can get well on the wing. It is quite a different affair when he is sighted winging his way high in the air over an open tract of country free from water. Though he has no chance in competing against a falcon in straightforward flight, the heron has large concave wings, and a proportionately light body, and he can rise with astonishing rapidity, more perpendicularly or, in other words, in smaller rings than the falcon can and with less effort. As soon as he sees the approach of the falcon, he makes for the upper regions. The falcon then commences to climb to get above him, but in a very different style. She makes wider circles or rings, travelling at a higher rate of speed, due to her strength, weight and power of flying, till she rises above the heron. Then she makes her attack by stooping with great force at the quarry, sometimes falling so far below him that she cannot shoot up to a sufficient pitch for the next stoop, and has to make another ring to regain her lost command over the heron, which is ever rising, and so on ---the "field" meanwhile galloping in the direction the flight is taking, till the falcon seizes the heron aloft, "binds" to him, and both come to the ground together. Absurd stories have been told, and pictures drawn, of the heron receiving the falcon on its beak in the air. It is, however, well known to all practical falconers that the heron has neither the power nor the inclination to use his beak in the air; so long as he is flying he relies solely on his wings for safety. When on the ground, however, the heron may use his dagger-like bill with dangerous effect, though it is very rare for a falcon to be injured. Old experienced hawks gen erally let go the heron on nearing the ground, "binding" to him again immediately he reaches it in his fall. Rooks are flown in the same manner as herons, but the flight is generally inferior. In Europe a cast of falcons was always flown at a heron. It was the practice to ride in and release the heron when he was taken, if uninjured the long plume of feathers at the back of his head being removed and kept as a trophy. The last establishment for heron hawking in Europe was maintained at the Loo in Holland, with H.R.H. Prince Alexander of the Netherlands as its president, between the years 1840 and 185o. This establishment was called the Loo Hawking Club and included several English members.

For game-hawking eyasses are generally used, though undoubt edly passage or wild caught hawks are to be preferred. The best game hawks we have seen have been passage hawks, but there are difficulties attending their use. It may perhaps be fairly said that passage hawks can be trained to "wait on" in grand style, but until they have got through their first season, they are more liable to be lost than eyasses. The advantages attending the use of eyasses may be summed up as follows : they are easier to ob tain, to train and to keep; they moult more regularly than pas sage hawks, and if lost in the field they will often return home by themselves, or remain in the country where they are accustomed to be flown. Experience and, we must add, some good fortune also are requisite to make eyasses good for "waiting on" at game. Slight mistakes on the part of the falconer, false points from dogs, or bad luck in serving, will cause a young hawk to acquire bad habits, such as sitting down on the ground, taking stand in a tree, raking out wide, skimming the ground, or lazily flying round at an insufficient altitude. A good game hawk in proper flying order mounts rapidly to a high pitch until she appears no larger than a swallow in the sky, keeping well over the falconer and dogs, and ready to stoop when the quarry is sprung. Hawks that have been successfully trained and judiciously worked become wonderfully clever, and soon learn to regulate their flight by the movements of their master. Eyasses were not held in esteem by the old falconers, and it is evident from their writings that these hawks have been much better understood and managed in modern times than in the middle ages. It is probable that the old fal coners procured the wild-caught hawks with greater facility than at the present day. There was a hawk mart held at Valken swaard in Holland, where hawks were sold after the annual catch during the autumn migration. It was visited by falconers from all over Europe, large sums being often paid at auction for par ticularly choice birds.

Here may be quoted a few lines from one of the best of the old writers, which may be taken as giving a fair account of the estimation in which eyasses were generally held, and from which it is evident that the old falconers did not understand flying hawks "at hack." Symon Latham, writing in 1633, says of eyasses: "They will be verie easily brought to familiaritie with the man, not in the house only, but also abroad, hooded and unhooded; nay, many of them will be more gentle and quiet when unhooded than when hooded, for if a man doe but stirre or speake in their hearing, they will crie and bate as though they did desire to see the man. Likewise some of them being unhooded, when they see the man will cowre and crie, showing thereby their exceeding fondness and fawning love towards him. . . . These kind of hawks which are (for the most part) taken out of the nest while verie young, even in the downe, from whence they are put into a close house, whereas they be alwaies fed and familiarly brought up by the man, untill they bee able to flie, when as the summer ap proaching verie suddenly they are continued and trained up in the same, the weather being alwaies warm and temperate ; thus they are still inured to familiaritie with the man, not knowing from whence besides to fetch their relief or sustenance. When the sum mer is ended they bee commonly put up into a house again, or else kept in some warm place, for they cannot endure the cold wind to blow upon them. . . . But leaving to speak of these kind of scratching hawks and I never did love should come too neere my fingers, and to return unto the faire conditioned haggard faulcon. . . ." The author here describes with accuracy the condition of un hacked eyasses which no modern falconer would trouble himself to keep. Many English falconers in modern times have owned eyasses which have killed grouse, ducks, and other quarry in a style almost equalling that of passage hawks. Moors, downs, open country where the hedges are low and weak, are best suited to game-hawking. Pointers or setters may be used to find the game, or the hawk may be loosed on reaching the ground where game is known to lie, and suffered, if an experienced one, to "wait on" till it is flushed. However, the best plan with most hawks, young ones especially, is to use a dog, and to "cast off" the hawk when the dog points, and to flush the birds as soon as the hawk has reached her pitch. The hawk should be well over the birds, and if possible a little up-wind of them when they rise, she will then be better placed for a down-wind stoop, as the game will not dare to fly up-wind under the hawk. The hawk will then turn over, and, flying headlong downwards with incredible speed, will, with the gathered impetus of her fall from the sky, rapidly over take the bird she has from the first moment selected as her victim. As she reaches it, she strikes it a heavy blow with the hind talon of her foot, and the bird falls to the ground, often stone-dead, leaving a cloud of feathers in its track, or, just as she rushes up to it, the quarry may evade the stroke by a clever shift, and hurl itself into the nearest cover before the hawk has recovered from her stoop. The falconer will then come up as quickly as possible to "serve" the hawk by putting the bird out again while she "waits on" overhead. If this be successful, she is nearly certain to kill at the second attempt. Falcons, being larger and stronger, are to be preferred for grouse and tiercels for partridges. Woodcock afford capital sport where the country is sufficiently open ; it will generally be found that after the first stoop at a woodcock, the cock will try to escape by taking the air, and will show a very fine flight. When beaten in the air it will try to get back to covert again, but when once a hawk has out-flown a woodcock, he is pretty sure to kill it. Snipe may be killed with first-class tiercels in favourable localities. Wild duck and teal are only to be flown at when they can be found in small pools or brooks at a distance from large sheets of water—where the fowl can be suddenly flushed by men or dogs, while the falcon is flying at her pitch overhead. For duck falcons should be used ; tiercels will kill teal well. The merlin is used for flying at larks, and there does not seem to be any other use to which this pretty little falcon may fairly be put. It is very active, but far from being, as some authors have stated, the swiftest of all hawks. Its flight is greatly inferior in speed to that of the peregrine. The hobby is swifter than the merlin, but cannot be said to be efficient in the field; it may be trained to "wait on" beautifully, and will take bagged larks: it is much addicted to the fault of "carrying." The three great northern falcons are not easy to procure in proper condition for training. They are difficult to break to the hood and to manage in the field. They can be flown, like the peregrine, at herons and rooks, and in former days were used for kites and hares. Their style of flight is magnificent ; they are swifter than the peregrine, and are deadly "footers." They seem, however, to lack somewhat of the spirit and dash of the peregrine. For the short-winged hawks an open country is not required; they may even be flown in a wood. Goshawks are used for hares, rabbits, pheasants, partridges and wild-fowl. Only very large and strong females are able to take hares; rabbits are easy quarry for any female goshawk and also for some males. For pheasants the male is to be preferred, and certainly for partridges ; either sex will take duck, but the falconer must get close to them before they are flushed, or the goshawk will stand a poor chance of killing. Rabbits may be bolted with the ferret, and the hawk loosed as the rabbit bolts, but care must be taken that she does not kill the ferret. Where rabbits sit out in grass or in turnip fields, a goshawk may be used with success, or even in a wood where the burrows are not too near. For various reasons gos hawks in England cannot be brought to the perfection to which they are brought in the East. In India, for instance, there is a far greater variety of quarry suited to them, and wild birds are much more approachable; moreover, there are advantages for training which do not exist in England. Unmolested, the Eastern falconer carries his hawk by day and night in the crowded bazaars, till the bird becomes perfectly indifferent to men, horses, carriages.

The management of sparrow-hawks is much the same as that of goshawks, but they are more delicate. They are flown in England at blackbirds, thrushes and other small birds ; the best will take partridges well early in the season. In the East a large number of quail are taken with sparrow-hawks. In India falconry, until quite recently, has always been a flourishing art. Indian falconers far surpass Persians and Arabs. Eyasses are not used, and the system of flying "at hack" is unknown. Hawks are caught on the passage, manned and trained to the lure in a wonderfully short time, but very seldom is a falconer to be found who can maintain hawks in good flying condition. In the Punjab, sakers are the falcons chiefly used; haggard and young passage hawks are flown at hares and hubara. Successful falconers get these sakers into good wind by daily exercise at the lure, giving them about 25 stoops in the morning, and about the same number in the evening. They are then kept fit by daily stooping to the lure. Arab falconers omit this exercise altogether, and keep their hawks in such poor condition that they are unable to kill hubara on the wing. Their hawks follow the quarry in the open desert, and when it settles, kill after a rough and tumble on the ground. During the last 3o years falconry has nearly died out in India, though a fair number of goshawks are still kept. Between the hours of II A.M. and 3 P.M. hawking in the desert is difficult on account of eagles, which interfere with the hawks, and rob them of their quarry. Pariah dogs too are liable to be a nuisance. Sakers, both haggard and young passage falcons, used also to he flown at kites. One flight each alternate day was usually con sidered sufficient, as this was a very tiring flight for the hawks. As kites are generally found in the vicinity of villages, and when pursued make for shelter in a village, kite-hawks generally come to an untimely end, being attacked by pariah dogs, or knocked in the head by the villagers themselves.

Hawks from which work in the field is expected should be kept in the highest health, and they must be carefully fed; no bad or tainted meat must be given to them. Peregrines and the great northern falcons are best kept on lean beef-steak with a frequent change in the shape of fresh killed pigeons and other birds. Freshly killed rabbits are a change to a lighter diet. The smaller falcons, the merlin and the hobby, require small birds to keep them in health. For goshawks a coarser diet, such as rats or rab bits, suffices. The sparrow-hawks, like the small falcons, re quire small birds. All hawks need to be given castings. Hawks will exist, and often appear to thrive, on good food without castings, but the seeds of future injury to their health are being sown. If it is more convenient to feed the hawks on beef-steak, they should frequently be given the wings, heads and necks of game and poul try, with the blood carefully removed. In addition to the castings which they swallow, tearing the pinion joint of a wing is good exercise for them, and biting the bones keeps their beaks in good trim. Most hawks, peregrines especially, require a bath. The end of a cask sawn to give a depth of about 6in. makes a good bath. Peregrines which are used for "waiting on" require a bath at least twice a week. If this be neglected, they are when flown inclined to soar, and may even rake away in search of water, and so be lost.

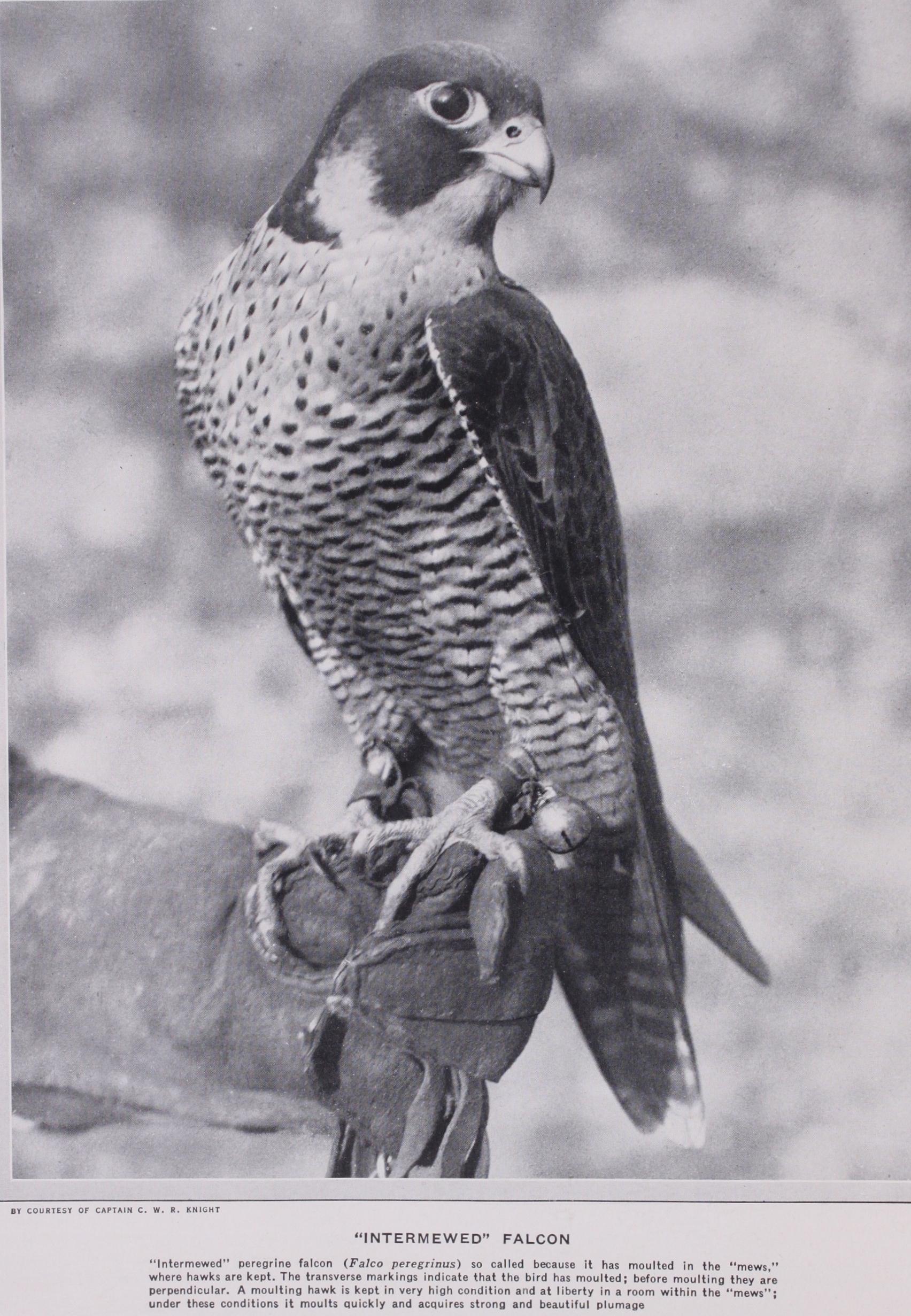

The best way, where practicable, of keeping hawks, is to tether them to blocks on the lawn. Goshawks are generally placed on bow perches, which ought not to be more than 8 or 9in. high at the centre of the arc. It will be several months before passage or wild-caught falcons can be kept out of doors; they must be fastened to a perch in a darkened room, hooded, and, by degrees, as they get tamer, they may be put out on the lawn. In England (especially in the south) peregrines, the northern falcons and goshawks may be kept out of doors all day and night in a shel tered situation. Merlins, being more delicate, should be given more protection. In wild boisterous weather, or in snow or sharp frost, it would be advisable to move them to the shelter of a shed, the floor of which should be laid with sand to a depth of 3 or 4 inches. An eastern aspect is best—all birds enjoy the morning sun and it is beneficial to them. The more hawks confined to blocks out of doors see of persons, dogs, horses, etc., moving about, the better. Those who have only seen wretched ill-fed hawks in cages, pining for exercise, with battered plumage, torn shoulders, and bleeding Ceres, from dashing against their prison bars, and with overgrown beaks from never getting bones to break, can have little idea of the beautiful and noble-looking birds to be seen pluming their feathers and stretching their wings at their ease on their blocks on the lawn, watching with their large, bright, keen eyes everything that goes on in the sky, and everywhere else within their view.

Contrary to the prevailing notion, hawks that have been well handled show a eood deal of attachment to their owners. It. is true that by hunger they are in great measure tamed and con trolled, and the same may be said of many undomesticated and many domesticated animals. Instinct prompts all wild creatures when away from man's control to return to their former shyness, but hawks certainly retain their tameness for a long time, and their memory is remarkably retentive. Wild-caught hawks have been retaken either by their coming to the lure, or upon quarry, from two to seven days after they have been lost, and eyasses from two to three weeks. As an instance of retentiveness of memory displayed by a hawk we may mention the case of a wild-caught falcon which was recaptured after being at liberty more than three years, still bearing the jesses which she wore at the time she was released ; in five days she was flying at the lure again at liberty, and was found to retain the peculiar ways and habits of a trained hawk. It is useless to bring a hawk into the field unless she has a keen appetite; if she has not, she will neither hunt effectually nor follow her master. Even wild-caught falcons, however, may sometimes become so attached to their owner that, when sitting on their blocks with food in their crops, they will, on seeing him, "bate" hard to get to reach him, till he either allows them to jump up to his hand, or withdraws from their sight. Goshawks too evince great attachment to their owner. Another error is that hawks are lazy birds, requiring hunger to stir them to action. The reverse is the truth ; they are birds of very active habits, and exceedingly restless. The wild falcon requires an im mense amount of exercise to enable her to exert her speed and power of flight ; instinct prompts her to spend hours daily on the wing, soaring and playing about in the air in all weathers, often chasing birds merely for play. When full gorged she takes a siesta; but unless she fills her crop late in the evening she is soon on the move again. Goshawks and sparrow-hawks, too, habitually soar in the air at about 9 or i o A.M., and remain aloft a considerable time, but these birds are not so active as the falcons. The fre quent "bating" of tame hawks proves their restlessness and im patience of repose. So does the wretched condition of the caged falcon, while the truly lazy buzzards and kites, which do not in the wild state depend upon their activity for their sustenance, maintain themselves for years even during confinement in good case and plumage. The falconer, therefore, should endeavour to give his hawks as much flying as possible, and he should avoid the mistake of keeping too many hawks. In this case a favoured few are sure to get all the work, and the others, possibly equally good, were they given the chance, are spoilt for want of exercise.

The larger hawks may be kept in health and working order for many years. The writer has known peregrines, shaheens and gos hawks to reach ages of 15 and 20 years. Goshawks, however, never fly well after four or five seasons, when they will no longer take difficult quarry; they may be used for rabbits as long as they live. Shaheens have been seen in the East at an advanced age, killing wild-fowl beautifully. The shaheen is a falcon of the peregrine type, but smaller, which does not travel, like the peregrine, all over the world. It appears that the jer falcons also may be worked to an advanced age. Old Symon Latham tells us of these birds—"I myself have known one of them an excellent hearnor (killer of herons) and to continue her goodnesse very neere twentie yeeres, or full out the time." (E. D.-RA.)