Fan

FAN, in its usually restricted sense denotes a light instrument held in the hand and used for raising a current of air to cool the face. Among the ancients the fan was also known as a winnower, as a bellows for fire and as a fly whisk. Modern usage also applies the word to an instrument for winnowing grain (winnowing fan) and to various appliances in systems of ventilation. (See FANS.) In the more familiar sense the forms of the fan may be divided into two main groups—the screen fan and the folding fan. In gen eral the former consists of a handle to which is attached a rigid mount ; except feather fans, which may be included in this class, the usual mount is made of straw, cane, silk, parchment, etc., and is square, circular, pear or leaf shaped. In some cases the mount is placed at one side, producing a flag-like form, such as the Venetian type of the i6th century, which was also known to the Copts of the early Christian era. The so-called cockade fan, which, as its name implies, has a circular pleated mount that may be folded flat, also belongs to this group. Types of the screen fan are to be found throughout the world in all periods, among both primitive and highly civilized peoples. The folding fan, although the better-known form, has a more circumscribed history. It is said to have been invented in Japan about A.D. 670. It was intro duced into China in the loth century and thence into Europe in the late i sth or early 16th century, probably at the time when the Portuguese under Vasco da Gama established themselves as the supreme trading power in the East. The folding fan is composed of sticks and a mount. The sticks are a number of blades, the one at each end being a guard; they may be ivory, mother-of-pearl or various woods, pierced, carved and often ornamented with inlay and gilding; all are fastened at the handle-end by a pin or rivet. The mount (or leaf), is pleated and stretched over the blades at the top, it may be made of paper, parchment, silk, lace and "chicken-skin" (an especially prepared kid-skin) or other ma terials, and is usually decorated with painting. A variant of the folding fan, popular in France in the i 8th century, is the cabriolet, which will be described later. The distinguishing feature of the brise fan is that it has no mount but is composed of a number of blades fastened at the handle-end by a rivet and radiating toward the top where they are connected by a ribbon ; the delicately carved ivory fans of China are exquisite examples of this type.

China.

The fan of the Far East is the most ancient known to us and is a separate chapter in the history of the instrument. Some authorities testify that in China fans have been known since about 300o B.C. The earliest form was of dyed pheasant or pea cock feathers mounted on a handle. Cockade fans and large cere monial screens are also of ancient origin while the small hand screens of various shapes, made of palm, bamboo and silk stretched on a frame, have been in use from ancient to modern times. Ivory fans seem to have come into being shortly after the folding fan was introduced into China. The Imperial ivory works within the palace at Pekin were founded in the i 7th century and became the centre of the best productions. The delicacy of carv ing in ivory brise fans can hardly be overestimated. Sometimes the decoration is made up of pierced, flat, open work, sometimes of elaborately carved figure or floral subjects with a background formed by ribbing of exquisite quality. Tortoise-shell was used in a similar way, also sandalwood and mother-of-pearl. Filigree fans of silver or silver gilt frequently inlaid with enamel form another variation. A class of Chinese folding fan often seen is the man darin fan with sticks of carved ivory and the leaf painted with innumerable minute figures with ivory heads and silk costumes applied. Almost every city or district in China has its character istic fan distinguishable by its colour and ornament and made to suit every class from mandarin to peasant.

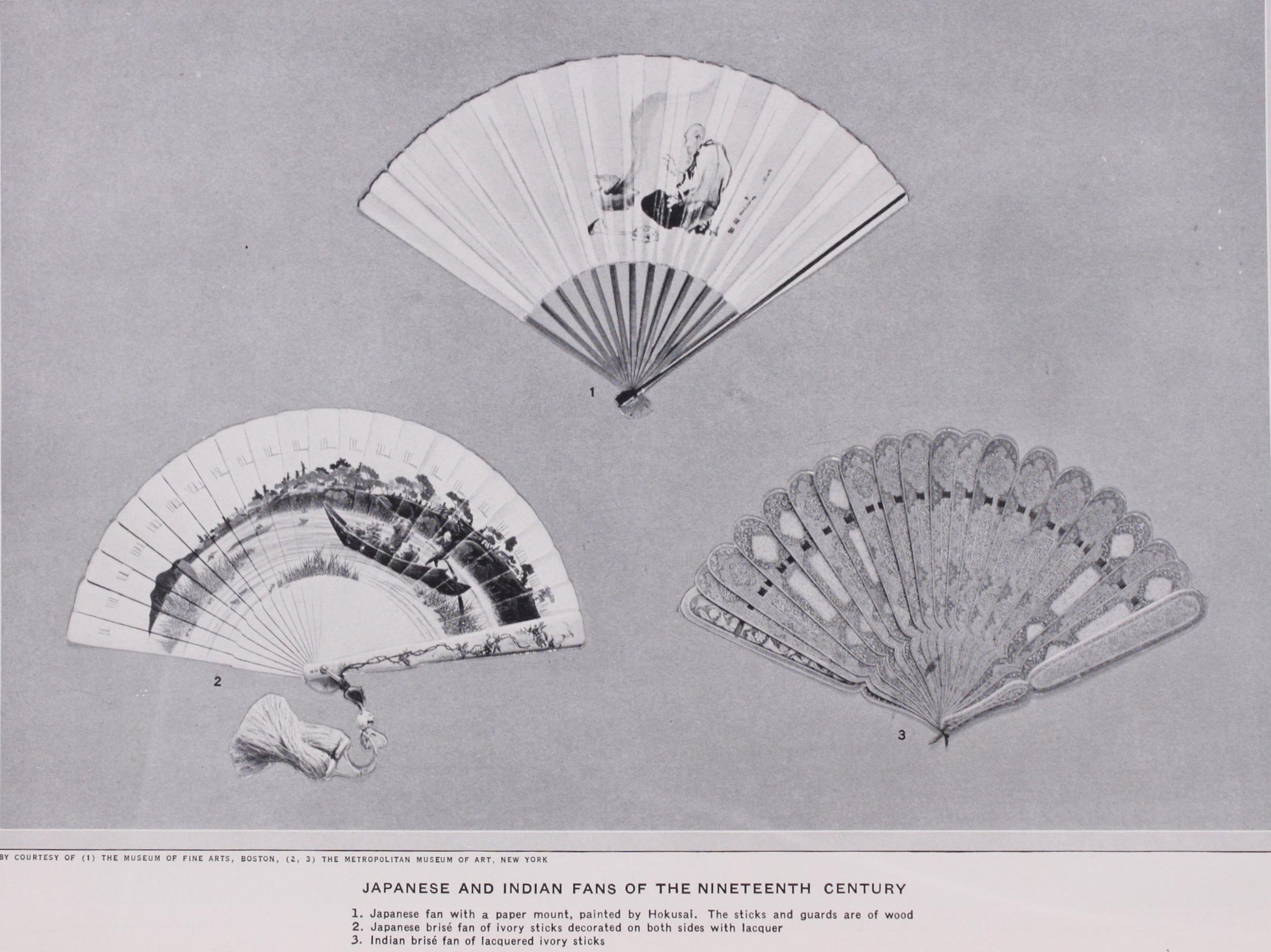

Japan.

In Japan also the use of the fan is very closely linked with the life and customs of the people. In Rhead's History of the Fan the author says that it is regarded as an emblem of life, widening and expanding as the sticks radiate from the rivet. It plays a part in almost every aspect of their existence : it is pre sented to the youth on the attainment of his majority; it is used by jugglers in feats of skill; the condemned man marches to the scaffold fan in hand. The earliest examples were made of palm leaves or feathers while the rigid screen fans were introduced from China in the 6th century A.D. Large screens were used for relig ious and civil ceremonial and as war standards. Most interesting of all the rigid fans is the Gumbai Uchuia, a type of battle fan of iron first known in the 11 th century. It is, however, the fold ing fan, invented by the Japanese in the 7th century, that has played such an important role in their history and art. There are innumerable variations of its form each designed for a particular use and possessing individual characteristics. The Akome Ogi is the earliest form of court fan having come into use in the 7th century; it is composed of 38 blades fastened with a rivet, formed of a bird or butterfly, and ornamented at the corners with arti ficial flowers and 12 long streamers of coloured silks; it was the type used by court ladies until 1868. The Gun Sen is the folding battle fan with sticks of wrought iron and the mount of thick paper painted with the sun, moon or star in red or gold on a black or coloured ground; its initial purpose in battle was as a signal. The Mai-Ogi or dancing fan dates from the i 7th century; it has io sticks and a mount of thick paper usually decorated with a family crest. The Rikin-Ogi or tea fan, used in tea ceremonies celebrated in each province on the first day of every month, has only three sticks and the paper mount is simply decorated, the fan itself being used for handing around little cakes, fanning being prohibited during this dignified ceremony. Many early fans were designed with the infinite artistry of the great painters of Japan but these are rarely seen to-day. Those most often found in collections are the modern brise of ivory or tortoise-shell dec orated with lacquer and inlay and often made for exportation to Europe. (See DRESS : Eastern.) Ancient.—In the cultures of ancient Egypt, Assyria and India, the fan achieved considerable importance both as a civil and reli gious emblem. Especially in Egypt fans played an important part in royal ceremony; the office of fan-bearer to the king was a highly prized honour ; their fans, made of feathers arranged in a half circle and mounted on long handles, may be seen in Egyptian wall paintings and reliefs. Two actual examples now in the museum at Cairo, were found in the tomb of Tut-ankh-amen (i4th century B.e.) ; the gold mounts with embossed and incised decorations were fitted with brown and white ostrich plumes and the handles were made in one case of gold and in the other of ebony overlaid with gold and lapis-lazuli. In India both the fan and umbrella were held in reverence ; the punkah or large screen fans are still hung in rooms and manipulated by servants detailed for the pur pose. In Greece peacock feather hand fans were known about Soo B.C. and may be seen in contemporary vase paintings while the rigid palm leaf shaped fan is frequently depicted in the terra cotta figurines from Tanagra. As for ancient Italy, an Etruscan cinerary urn in the Metropolitan Museum of Art shows the deceased in the customary reclining posture holding in her hand a feather fan; and in Rome tablet fans of precious woods or finely cut ivory were carried by the exquisites on the Via Sacra for their ladies, while another type was always part of the bridal outfit of a Roman woman.

Mediaeval.

In the Middle Ages the Christian Church per ceived the usefulness of the fan in religious ceremonials. The flabelluna, as it was called, a disc sometimes of silver or silver gilt mounted on a long handle, was held by deacons and used to drive away flies and insects from the sacramental vessels. Accounts of the nobelium occur repeatedly in the old inventories of church and abbey property but except for two, whose use was probably secular, no fans of the period exist to-day. With the exception of the large feather fan carried in state processions for the pope, the fan is no longer used in the Western Church, but it still appears in the rites of the Eastern Church. The two famous speci mens mentioned above, of the mediaeval period, are of the cock ade type with mount of vellum and handle of carved bone. One of these dating from the 1 1 th century from the abbey church of Tournus is now in the National museum at Florence while the other, said to be the oldest existing Christian fan and identified with Theodolinda, queen of the Lombards, is now preserved as a sacred relic in the cathedral of Monza near Milan, where super stition has invested it with magic powers.

Modern European.

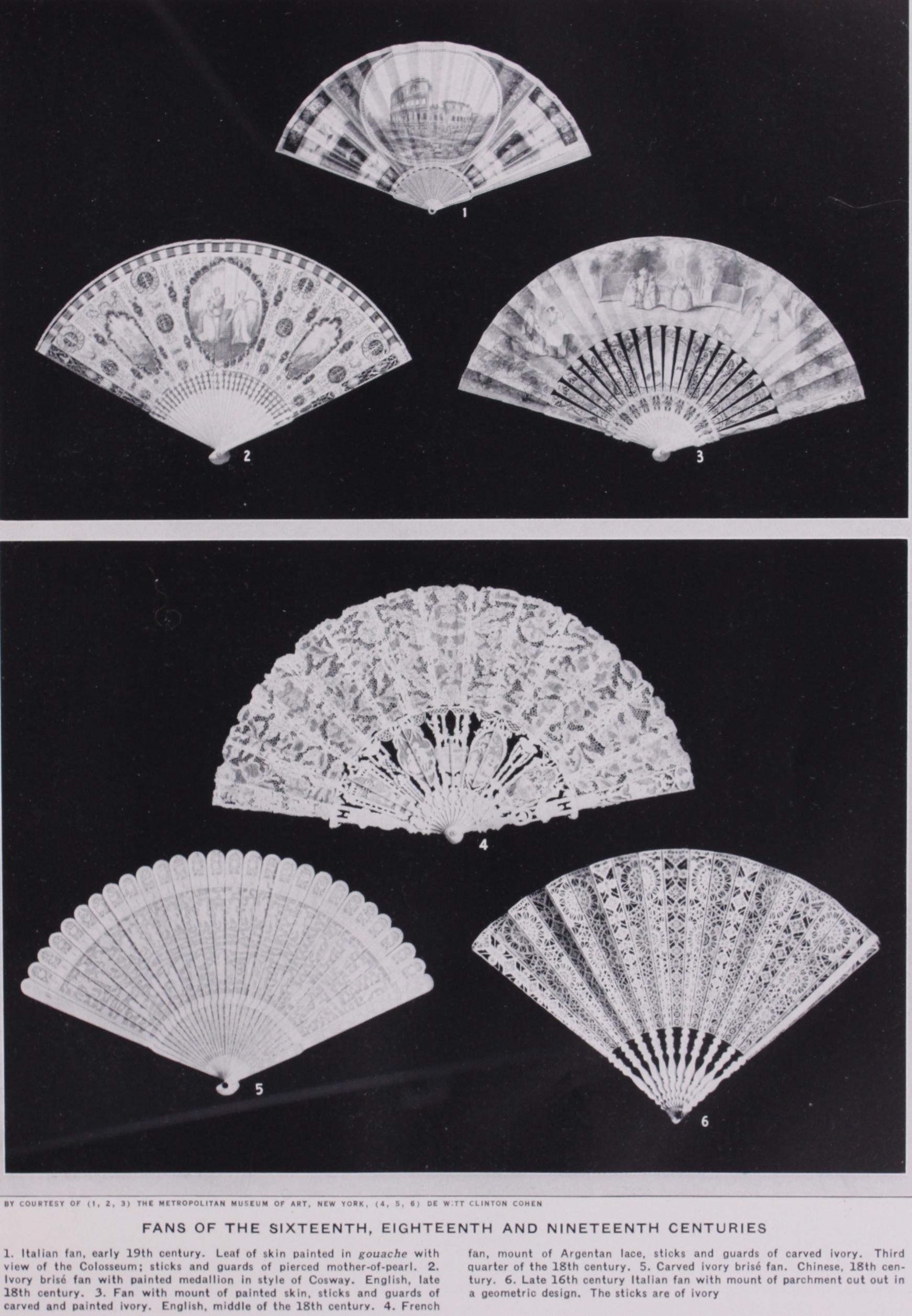

The vogue of the folding fan in Europe dates from its introduction through Portuguese trade connections with India and the Far East in the i6th century. Although it may have been known earlier, the impetus supplied by oriental impor tations produced a new era in its evolution. In popularity it soon supplanted the feather fan mounted on a carved ivory handle and the Venetian flag-like instrument. The type of folding fan found in late i6th century portraits is about a quarter circle in shape with sticks of ivory and a mount composed of alternate strips of vellum and mica, or of vellum cut out in a geometrical pattern of circles and lozenges similar to the designs of reticello lace of the period. Of this kind, called decoupe from the perforated vel lum mount, there is a beautiful example in the Cluny museum and one almost identical in a private collection in New York. It was at this time that the vogue for fans, already general in Italy and Spain, spread to France and England. Although not then confined to the use of ladies, special conventions were developed and gestures in handling them grew into code signals of amorous import.In the 17th century Paris became the centre for the manu facture of fans. Louis XIV. issued edicts at various times for the regulation of the industry and in 1678 the Fanmakers' Guild was formed. The revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685) drove many fanmakers to England and Holland. In consequence a fan trade was established in England where, after the formation of the Fanmakers' Company (1709), the importation of foreign fans, especially from India and China, was for a time prohibited. During this period the shape of the fan gradually grew to a full semi-circle with sticks of ivory or mother-of-pearl pierced or carved. The mounts of paper, vellum, parchment and specially prepared kidskin were painted or engraved, often from designs of such artists as Lebrun, Romanelli, Abraham Bosse and Callot.

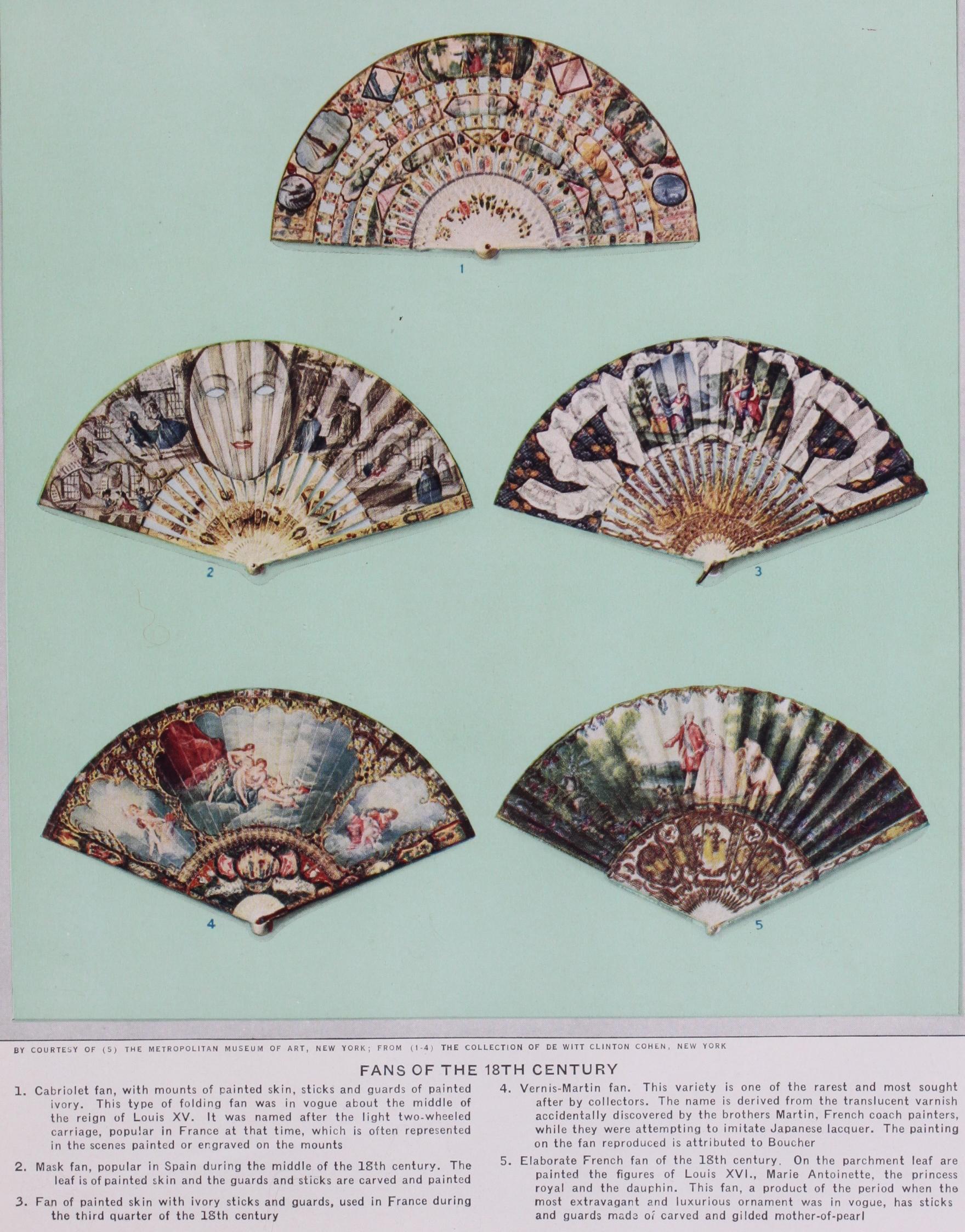

It was, however, in the 18th century that the most extravagant and luxurious ornament was expended upon the decoration of the fan. The delicately carved sticks of ivory and mother-of-pearl, sometimes the product of Chinese workmen in Europe, were fur ther enriched with incrustations of gold, silver, enamel and jewels. The mounts were made not only of skin but of silk, lace and paper perforated in imitation of lace, while the suave and gracious designs with which they were painted followed the fashion set by the chief artists and decorators of the day. As it was an age of considerable decorative invention, it is not surprising that new forms of the folding fan should appear. One of the rarest and most sought after by collectors is the so-called Vernis Martin. In form this type of fan is an ivory brise, the blades of which are painted in thin oils and then varnished. It is from the par ticular translucent varnish that the name is derived, for in at tempting to imitate Japanese lacquer, the brothers Martin, coach painters by trade, accidentally developed a method suitable for this decoration. Vernis Martin fans are smaller in size than the usual type of the period and because of their interest to collectors many imitations have been made. About the middle of the reign of Louis XV. another type of folding fan, the cabriolet, became the vogue. This was a reflection of the immense popularity achieved by a light two-wheeled carriage introduced to Paris by Josiah Child in 1755. For such fans, the mount instead of being one broad strip, was composed of two or sometimes three narrow strips with an intervening space between them. The strips were then painted or engraved with small scenes which usually in cluded representations of people driving about in the fantastically popular carriage itself.

Toward the end of the reign of Louis XV. the fan industry suffered from a vogue for cheap printed fans. The sticks were thin and often undecorated, the printed paper mounts frequently depicted incidents and personages connected with contemporary political events. Some of the most interesting of these fans com memorate the balloon ascensions of i 784 and 1785 and the meet ing of the Estates General in 1789. Other more pretentious fans of the period were much ornamented with spangles and tinsel, often with cheap effect. In England at this time there developed a particular type of ivory brise fan—the ivory pierced and deco rated with medallions painted in miniature in the style of Cosway or Angelica Kaufman.

During the period of the First Empire fans retrieved very little of their past elegance. They were small, delicate instruments often with mounts of spangled gauze and sticks of pierced ivory. The lorgnette fan, a variant of the cockade form, was made of pierced horn or ivory and had a little glass inserted at the rivet. As the century advanced the romantic and antiquarian tastes of the Victorian era were reflected in the style and decoration of fans There was much lifeless imitation of the Louis XV. types, and there were many large fans with mounts of lace or, f re. quently, paper with coloured lithographic prints of romantic scenes. The sticks of mother-of-pearl were pierced and gilded and except in rare cases, were coarse in both design and execution. The invention of Alphonse Baude in for carving sticks by machinery reveals the lack of taste and discriminating quality of the time, for no mechanical contrivance can duplicate the verve . of hand-carving. Somewhat later, however, certain fan-makers attempted to revive the old distinction of design and workmanship. Exhibitions were held in Paris and at South Kensington (187o) and painters of repute made designs for fan mounts, among whom may be cited Gavarni, Diaz, Couture, Solde, Jacquemart and Charles Condor (1868-190o) (q.v.).