Farm Management

FARM MANAGEMENT. This subject is considered in this article solely in its relation to the farmer as a business man. The scientific production of crops and livestock products is considered elsewhere in these pages.

Farming is a one-man business in the sense that it is carried on entirely by relatively small capitalists; there is no joint-stock enterprise in British agriculture. In this respect the farmer as a business man has lagged behind his brother in urban industry. The village craft has given place to the factory or the foundry with all the opportunities presented by large scale organization for mass production, specialization of labour and scientific manage ment of every kind. The farm regarded as a unit of production remains practically what it has always been, with only such modi fications as have been introduced by the partial change from self sufficing agriculture to production in a greater degree for the mar ket. This failure on the part of the farmer to participate in what has come to be regarded as progress in industry can hardly be charged against him as evidence of want of imagination or organiz ing ability. There is probably something inherent in agriculture, as practised in this country, which makes it a one-man business. Production from the land is carried on under conditions which change from day to day and from season to season, so that de partmentalization of production and specialization of labour, which are characteristic features of large scale enterprise, are impossible. A man cannot be set to drill wheat all the year in the way that a man can be set to fit tyres to the wheels of motor-cars, for wheat sowing lasts for but a short time in the year. Even during that period the work may be interrupted by conditions of the weather, and though the contrast is less sharply marked in the case of workmen engaged entirely in the care of livestock, it is true to say that owing to the dovetailing and interdependence of the various departments of the farm and the rapid decisions as to the work of the employees which is called for, specialization of management may be as difficult as specialization of labour, and the size of the farming unit must be determined by the limitations of the individual manager.

It should be noted that these conclusions are drawn from the study of farming as it is and as it always must be in many parts of Great Britain. It is not impossible to visualize conditions under which, by a completely new conception of farming, large-scale production, with its attendant advantages and difficulties, might even find its way into agriculture. If it were possible to eliminate much of the "mixed" nature of farming and to limit production over large areas to one or two commodities, on the analogy of the tea and coffee and rubber estates of tropical countries, the joint-stock system might find its place. This is a large question, outside the scope of the present article.

Farm Capital.

As regards the provision of capital for his industry the farmer's position is almost unique. Under the sys tem of land tenure which has prevailed for the last century and is half it has been the practice for his landlord to supply the capital for what would be regarded as the factory of the industrialist, and to maintain it in tenantable condition for him in return for a small annual rent. Whereas the urban manufacturer has to allocate a certain portion of his capital to the purchase of land and to the erection of the buildings necessary to his trade thereon, the farmer is provided with a factory more or less completely equipped and ready for use. This is a condition which is really essential to the one-man organization of the farming industry. The amount of capital required to buy and build the average agricultural holding and to stock it with the live and dead stock necessary would be far beyond the means of the individual capi talist, and any extensive upheaval in the old arrangement of this partnership between landlord and tenant will require either that the landlord's functions should be assumed by some other party, or that the size of holdings be reduced to the point at which the money now employed as working capital upon larger units will be sufficient to cover what we may term the fixed capital, repre sented by the land and buildings, in addition.As regards working capital, the farmer is cut off from some of the sources available to other people by the relative insignificance of his business. He cannot appeal direct to the investing public.

Thus he is limited to his own resources and to the estimate of his credit-worthiness which the bankers and traders with whom he deals are prepared to make. This operates against him in two ways. The joint-stock banking institutions lend large sums to their agricultural customers, but farming suffers from a slow turn over (the wheat crop, for example, may require financing for two years from the date of the first ploughing until the date of de livery to market) and long-term credit makes no great appeal to the banks. This drives the farmer to the merchant from whom he buys his requisites, or to the cattle-dealer or the auctioneer from whom he buys his livestock, for the further credit he may require, and although many farmers owe much to their friends engaged in these occupations, the loss of independence which the practice entails is open to many abuses, which need hardly be enumerated. Thus in these two ways, the unsuitability of bank credit for a slow turnover, and the tying of the farmer to his merchant where merchant credit is sought, the farmer is at a disadvantage in securing access to adequate capital resources. It is true that in this respect his case is no different from that of other small manufacturers, but there is no other industry of the magnitude of farming which is comprised so exclusively of little capitalists. No satisfactory system of agricultural credit adapted to the needs of farmers in Great Britain has been devised. In the peasant countries of Europe and elsewhere credit has been organised on a co-operative basis, the members of the society assuming unlimited liability for each other. This works well enough in peasant communities, where every man's business and character is known. In England, where the small cultivator of fifty acres may have as his neighbour the tenant of a thousand acre farm, co-operative credit on this analogy is obviously un workable. The most promising proposal is that which contem plates the linking up of credit with farmers' co-operative trading societies. Societies for the sale of farmers' requisites on the co operative principle are common throughout Great Britain, but both their membership and the volume of trade they do are re stricted by their rules of business. These are modelled on those of the industrial co-operative societies, under which transactions with members must be for cash only. It is obvious that there can be no advantage, and even certain danger, in extending credit to the industrial co-operator purchasing goods for consumption out of a weekly wage ; it is equally obvious that there is every reason for extending credit to the agricultural co-operator pur chasing the requisites and raw materials for the manufacture of his commodities, the process of which will occupy many months. So long as the agricultural co-operative supply societies insist upon cash payments, so long will their membership be a restricted one and the opportunity for solving the farmers' credit problem will not be attained.

Farm Labour.

In its relations with labour, British agriculture is in the same position as those other industries which are regu lated by the decisions of a trade board. Even in the days of pros perity before the great agricultural depression of the 'eighties and 'nineties of the last century, the farming industry can only be re garded as a sweated industry, and all attempts to organize the rural worker on trade union lines failed, partly owing to the general diffusion of the agricultural population, as opposed to the con centration of the workers in urban industry, and partly owing to the decline in the demand for labour under modern systems of farming. In these circumstances, and having regard to the trend of public opinion, the setting up of an agricultural wages board sooner or later was inevitable, and wages are now regulated in every county by the decision of the impartial members of a tribunal, where the representative members are unable to agree. It is unfortunate for the farmer that the standard by which these wages are regulated must be inevitably those of the great mass of the community engaged in urban industry, whereas the competi tors of the English farmer in many parts of the world are living at a lower standard. In these circumstances it is essential that everything be done to increase the efficiency of the English agri cultural worker as measured by the value of his output, and it is here that some criticism of his employer may be justified. Com plaints of the inefficiency of the farm labourer are general, but there is no apprenticeship of boys, nor any organized instruction for them in farm work. They pick up what they can. As adults there is no study of their work on the lines made familiar through scientific management of industry, and too little consideration of the point at which the expense of manual labour under present day conditions becomes prohibitive and at which it is an economic necessity to multiply its efficiency by mechanical power. For a century the labourer was the farmer's cheapest machine and he has not yet fully adapted himself to new conditions.

Distribution of Farm Produce.

Thus far the British farmer has been considered as a business man solely in relation to production. The question of the distribution of his product is probably even more important at the present time. With the re muneration of his workers controlled by a wages board, and with the raw materials of his industry in the hands, for the most part, of powerful combines, there is perhaps little scope for the farmer in the direction of reduced costs of production. On the other hand, he has never given serious attention to the possibility of economies in the traditional methods by which his produce reaches the consumer. The farmer has regarded himself as a producer and has been content to leave the process of distribution to be organized for him from the outside. The result has been the evolution of a chain of distributive services of extraordinary convenience to him. England is covered with a complete net-work of markets and fairs, for the sale and purchase of livestock of every descrip tion. In every town of England there is a corn exchange. or mer chants attend on regular days to purchase the farmers' corn.

The system is so convenient, so fatally easy, that its economic weaknesses are too often obscured. The object of the farmer should be to reach the consumer by the most direct route. This involves the bulking, grading and processing of his products and their ultimate distribution amongst consumers with different re quirements. Take, for example, the case of fat cattle. The farmer will take his beasts, possibly one or two at a time, to the local market. Here they will be offered to a highly organized group of buyers, competition amongst whom is still further reduced by reason of their different requirements. Some will require fine quality large cattle for a hotel or restaurant trade ; others prime quality small cattle for high class family trade ; others again will want the inferior stock for the lowest class of industrial demand. The small quantity of stock on offer at scores of little country markets will only attract a few buyers, whose self interest in forming a "ring" is as obvious in its policy as easy in its achieve ment. The buyers at these small markets may be buying for their own requirements or they may be collecting stock for re-sale in the larger markets in the great consuming centres, and the waste fulness of this method of distribution needs no explanation. What is wanted is a system of farmers' abattoirs, conveniently placed all over the country, to which fat stock should be sent without entering a market at all, for slaughter, grading of carcases, and sale direct to the retailers by grade and description. (See F. J. Prewett, The Marketing of Farm Produce, Part I. Livestock.) All the movement of fat stock about Great Britain, with its attendant expense and deterioration, would be obviated in this way; butchers' rings to depress prices would be impossible; and the farmer would secure the full value of his product.

What is true of the marketing of fat cattle is equally true of other products. Take, for example, milk. Milk is produced for two purposes, namely—for consumption as liquid, and for manu facture into milk products. At the present time milk is produced in roughly equal quantities for either purpose. As regards price, it is obvious that the key to the situation lies in the control of the manufactured portion. If the producers can manufacture all that portion in excess of the requirements for liquid consumption they can control the price of liquid milk. On the other hand, if they have no organization for manufacture, and insist upon sell ing the whole of their production as liquid milk, leaving it to the purchaser to organize the manufacture of that portion which is surplus to requirements of liquid consumption, then it is the purchaser and not the producer who will dictate the price of milk.

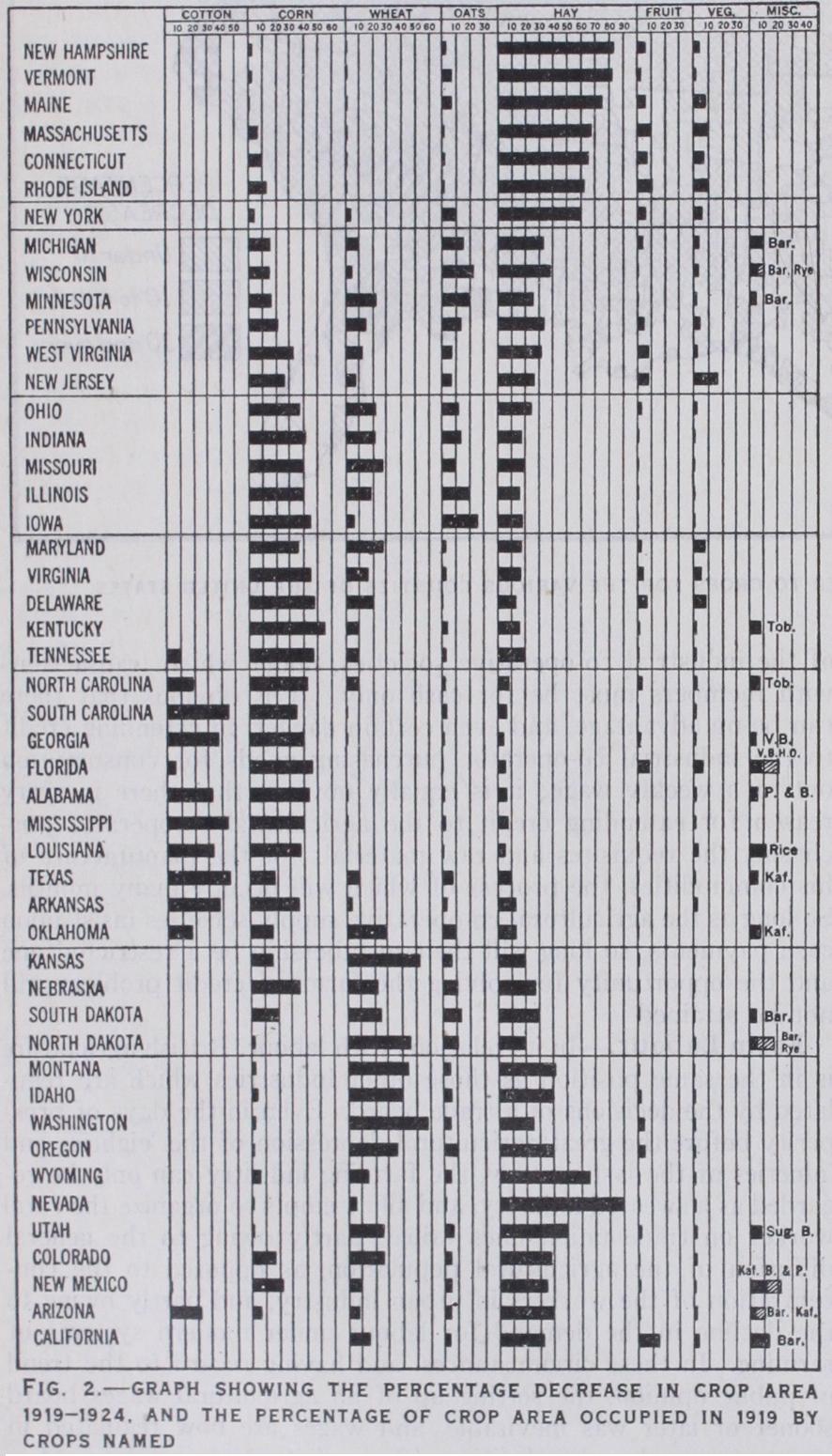

Obviously what is needed in the agricultural industry is the or ganization of producers upon a co-operative basis for the distri bution of their goods. There are many examples in various coun tries of what has been achieved by producers in this way. It must be noted, however, that in nearly every case these are countries farming to supply an export market, and where all the products of the land have to pass through a bottleneck, so to speak, to reach their destination overseas. Under these circumstances the organization of producers is immensely facilitated, whereas the task in a country like Britain, where everything grown can be sold virtually at the farm gate, presents much greater difficulty. The farmer, too, is apt to be a fierce individualist, the idea of corn bination cuts across his notion that he can generally get the ad vantage in a deal, and the fact must be admitted that no society of British farmers has succeeded yet in putting up a market ing organization which can give a service of efficiency equal to that of the private trader. If British farming is to retain anything more than a semblance of prosperity it is certain that many of the farmers' business methods will have to be reconsidered and ulti mately reconstructed. (See also AGRICULTURAL CO-OPERATION ; AGRICULTURAL CREDIT ; AGRICULTURAL ORGANIZATION ; AGRICUL TURAL MACHINERY.) (C. S. 0.) In the United States the organization of the farm is looked upon as an important part of the work of the farm manager. Farm organization and farm operation are therefore regarded as the two principal divisions of the subject of farm management; they are so presented in agricultural schools. The problems of farm organization and of farm operation overlap to a considerable extent, particularly in the matter of adjusting cropping systems and complements of livestock to changing economic conditions.