Farm Rents

FARM RENTS. The rent of an agricultural holding is the consideration paid for its use by the occupier to the owner. It may be paid in produce, in services or in money. Feudalism, which was for centuries the dominant agrarian system in Europe, re sulted, in the end, sometimes after serious political disturbance, in the emergence of two main classes—peasant proprietors and tenant farmers. In Great Britain the manorial organization from the earliest times included a number of small occupying-owners (eventually the class of yeoman-farmers), but the great majority of the cultivators were "villeins" occupying their allotted shares in the common field on terms of service (see LAND TENURE).

The first stage in the development of farm rents was the definite fixing of the amount of service, i.e., the number of days' labour, which the tenant was bound to render to the lord of the manor. Concurrently the practice of payment in produce instead of, or in combination with, services arose. In a typical instance cited by Thorold Rogers the rent was partly produce and partly labour— a quarter of seed wheat at Michaelmas, a peck of wheat, four bushels of oats and three hens on Nov. 12, a cock and two hens at Christmas, with the obligation to plough, sow and till an acre of the lord's land, and some other services. The only money payment was a halfpenny on Nov. and a penny at every brewing.

This was in the 13th century, but a change was rapidly taking place. Landowners required money to maintain the rising standard of living and to meet the charges falling upon them. With an extending market larger and more enterprising tenants were able to sell increasing quantities of their products. The commutation of produce and service rents into money payments was in the interest of both classes and proceeded rapidly, the process being accelerated after the Black Death. By the end of the 15th cen tury money rents were general although the old tradition was often perpetuated by still including some produce in the terms of the agreement. Even as late as the 18th century traces of pro duce rents were often found among the conditions of a farm lease.

Comparisons of modern rents with those paid in the middle ages have little meaning owing to the changed value of money. Soon after the beginning of the era of improved farming, in the latter part of the 18th century, Arthur Young estimated the average rent of English farms at 1o/- per acre. Thereafter there came during the Napoleonic Wars a substantial rise in rents. But after Water loo there was a collapse. Landlords were reluctant to recognise that the high prices of the war period were due to temporary causes and rents were often kept up until many farmers were ruined and large tracts of land were left untenanted. Nevertheless it is stated that by 1816 reductions of rent had amounted to a gross total of £9,000,000. The depression lasted for over 20 years, but after 1840 there was a marked recovery, and agriculture en tered on a period of prosperity during which rents rose steadily until 1880.

During the next 20 years rents fell almost continuously but at the beginning of the 19th century they reached something ap proaching stability. The World War saw no such raising of rents as characterized the war period a century earlier, and although farmers made high profits landowners generally profited little. After the World War many estates were sold and there was some increase of rents generally especially where the land had new owners.

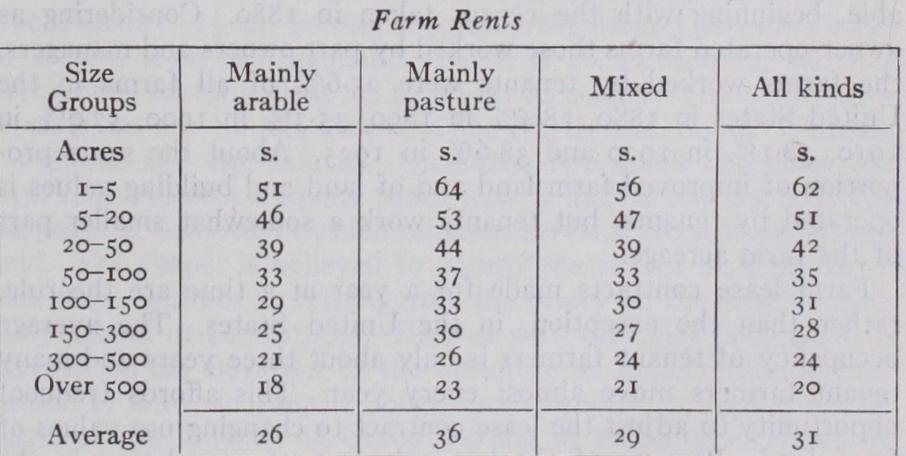

Average Rents: 1925.

In 1925 the Ministry of Agriculture obtained estimates, through their crop reporters, of the average rent paid in England and Wales for eight different sizes of agri cultural holdings, distinguishing in each case between (I) holdings mainly arable (70% and over arable land), (2) holdings mainly pasture (70% and over pasture), (3) mixed holdings lying be tween these two groups, (4) fruit and vegetable farms, and (5 ) poultry farms.The average rents per acre paid for holdings in each of the three chief groups are shown in the following table :— The average rent of fruit and vegetable farms was 82/- per acre and of poultry farms 64/- per acre.

In comparing size groups it is to be remembered that as the rental of a farm includes not only the land but the farm house and buildings the rent per acre naturally tends to diminish as the acreage increases. (R. H. R.) The history of agricultural rents in the United States of America commences with its colonial period, during which many proprietors who had received large grants of land in colonies south of New England attempted to collect quitrents from those who occupied their land. In general, the annual quitrent pay ments were evaded, resisted and made tardily, if at all. This failure of the quitrent system hastened the breaking up of the large land holdings. Sales were facilitated where full title passed. Except in sections of the South where plantations exist, the ma jority of individual landlords now own but one rented farm each, and about half of all rented farms in the country are thus owned. Cheap land or free land on which a squatter might live was so plentiful in early colonial days that unless a farm was unusually well improved or situated it had little rental value. But from early times there have always been farmers who have preferred the greater comforts and certainty of existence as tenants on im proved farms of older settled neighbourhoods to pioneer life on land which they might own along the westward moving frontier.

Except as grantor of grazing permits in national forests, the Federal Government, the original owner of a large part of all lands in the United States, has never attempted to fill the role of landlord. The general policy of the Government has been to get the public domain into the hands of private owners as rapidly as possible. There is still much land open for occupation, but be cause of the marginal or sub-marginal character of this land not much of it is now passing into private ownership and it has little effect on prices and rentals paid for land already in private own ership. Permits are sold for grazing privileges in the national forests but the amount charged the stockowner is based on the kind of live stock, the number of head and the number of months' grazing, and does not concern a definite area of land rented for a definite period of time. Fees charged for permits to graze in the national forests have been adjusted upward and, when in full effect, will vary with the value of each range, averaging about 14.4 cents per month for cattle and 4.5 cents per month for sheep. Formerly a flat rate of 10.4 cents per month for cattle and 2.9 cents per month for sheep was charged for all permits on all ranges (see Report of the secretary of agriculture, p. 79, 1927).

Many of the States have held land and while much State land has been leased to private individuals pending sale, it has been the general policy of the States as owners of agricultural land to dis pose of it by sale to individuals. The rents collected by the States have rarely been looked upon as a permanent source of income. During the 18th century agricultural writers frequently mentioned the fact that land was rented. By 1843 a correspondent to one of the farm papers says that one-fourth to one-third of the farms in a New Jersey county were rented, mostly for a share of the product. Other notes of a similar kind indicate that the practice of renting land was early established in all the older communities. Statistics on agricultural tenancy in the United States are avail able, beginning with the census taken in 1880. Considering as owner-operated farms those worked by part owners and managers, the farms worked by tenants were 25.6% of all farms in the United States in 188o, 28.4% in 35.3% in 2900, 37.0% in 1910, 38.1% in 1920 and 38.6% in 1925. About the same pro portion of improved farm land and of land and building values is operated by tenants, but tenants work a somewhat smaller part of the farm acreage.

Farm lease contracts made for a year at a time are the rule, rather than the exception, in the United States. The average occupancy of tenant farmers is only about three years and many tenant farmers move almost every year. This affords frequent opportunity to adjust the lease contract to changing use values of farm land. Because of the large element of speculation in the value of farm lands in the United States, the prospective income from increments in value has been prevalently considered as sup plementary to rentals. In many sections of the country the capi talization of expected increments has caused net rentals to appear to be a small percentage of return on capital values. Net rentals from agricultural land are much less than they were before 1914. Cash rent rose with land values up to 1920 and, like them, has fallen since that year. Share rent increased in value with the higher prices received for farm products and has fallen as the price level of agricultural products has fallen. Taxes on farm real estate rose with other things, but have not fallen to the ex tent that the gross incomes available for tax payments have fallen, and this circumstance has seriously reduced net rentals. An indi cation of the trend of gross rents in fertile areas may be found in Iowa, which is in the heart of the principal maize-producing section. Cash rent per acre for farm land in Iowa for specified years was: 1900, $3.29; $3.57i 1910, 1920, $8.28; 1925, $7.03. (Figures for 2900-15 inclusive are given in U.S. Dept. of Agr. Bulletin 1224 and for 1920-25 are from the U.S. Census.) Taxes on rented farm real estate are generally paid by the owners. The depression in agriculture, however, has caused so many farmers to turn to other ways of getting a living that much farm land is wholly unoccupied in the poorer sections, and much of the mediocre land may be leased on terms which do not return landowners a sufficient income to meet the taxes currently levied against it. In the United States more farms are worked by ten ants on shares than are rented for a fixed amount payable in cash. The census of agriculture for 1925 showed 393,452 farms rented for cash and 2,069,156 farms worked by tenants, who either rented entirely on shares, or rented part of their land on shares and part for cash. An additional group of 554,842 farmers owned a part of the land they farmed and rented the rest of it from other landowners for cash or on shares. As compared with 1920, these figures reveal a comparatively large decline in cash renting and an increase in other forms of rent payment. Cash-rented farms outnumber farms occupied by other tenants only in a few agri culturally unimportant States. On most farms leased for a fixed amount of rent in cash or kind the rent to be paid in the next year is determined in the autumn, by competition for land by tenants and for tenants by landowners. This competition is largely controlled by the current prosperity of the tenant class and by the outlook for the ensuing year. In 1920, in the 16 southern States, 104,996 farms were occupied by standing renters; i.e., renters who pay a fixed amount of product, such as so many bales of cotton. Two-thirds of this class were in Georgia and South Carolina, principally in a belt of Piedmont cotton counties. In share renting the agreement varies with respect to points such as the contribution of the work, stock, equipment, fertilizer and miscellaneous expenses, as well as with regard to the share each party is to have in the proceeds. On many farms primarily leased on shares there are certain fields, pastures or perquisites for which the tenant pays cash rent. Cash rent is seldom paid on farms from which the landlord gets a share of the live stock receipts. The payment of cash rent on crop share rented farms often is to compensate the landlord for the fact that the tenant has oppor tunities to obtain an income from live stock kept on fields from which a crop may not be sold to advantage.

Three-tenths of the two million and more farm tenants who paid something other than cash rent for the use of land in 1925 were croppers farming in the southern part of the United States. For all practical purposes the majority of croppers may be de scribed as married labourers without capital of their own, hired to raise a cotton crop in which they are given a half share interest in lieu of wages, and advances secured by that share interest so that they and their families may live while making the crop. Croppers constitute the major exception to the rule that in the United States farm tenants own the work animals and the farming equipment. (0. M. J. ; H. A. T.)