Fault

FAULT, a failing, mistake or defect. (Mid. Eng. faute, through the French, from the popular Latin use of fallere, to fail; the original 1 of the Latin being replaced in English in the i 5th century) .

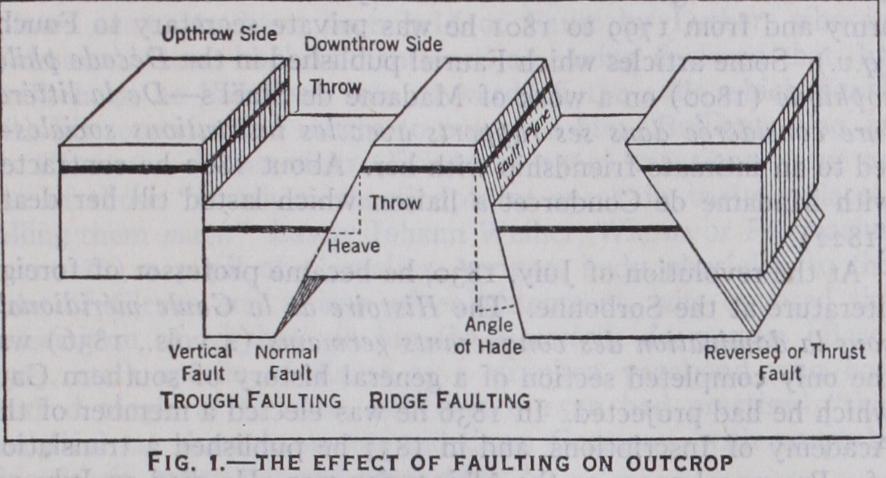

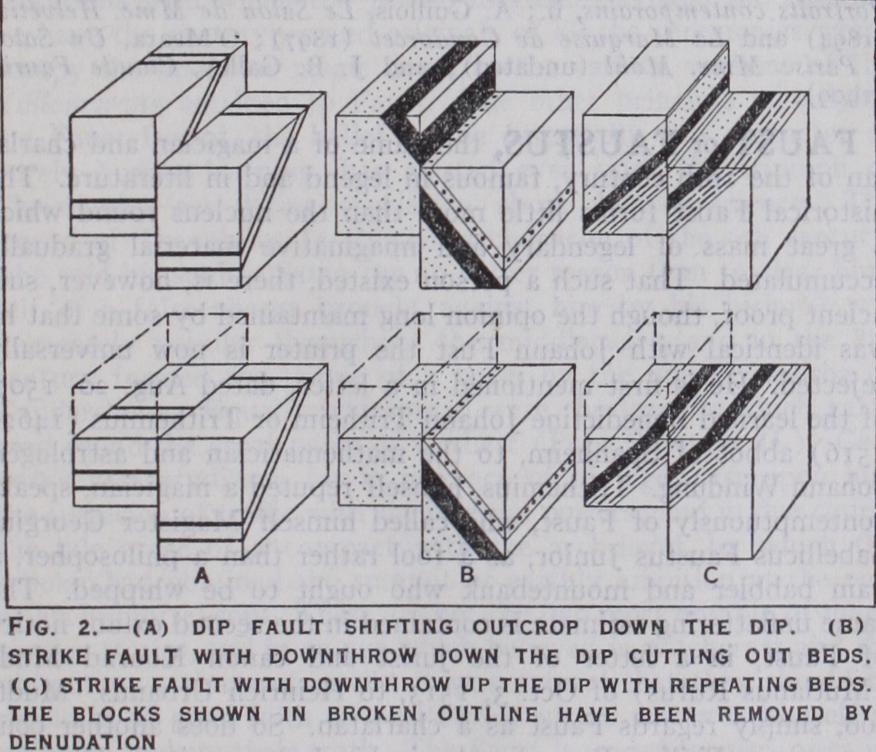

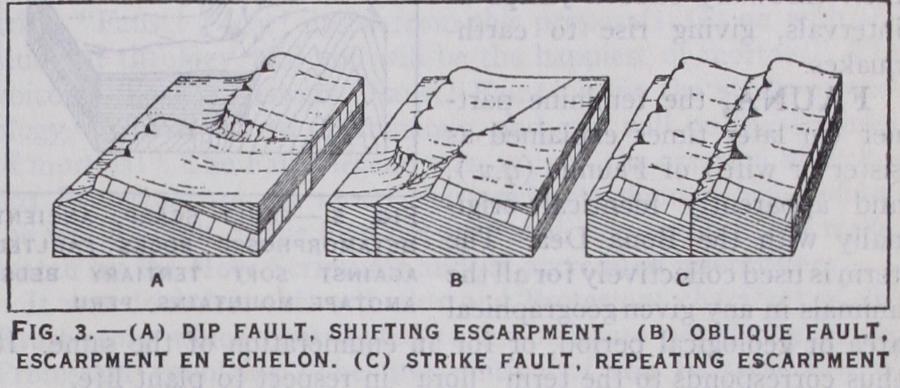

In geology, a fault is a dislocation in rocks, the result of crustal movements. Faults differ from joints in not being simply cracks, but fissures when differential movement of the two sides has taken place. The three principal types are known as normal faults, reversed faults or overthrusts and transcurrent faults. The surface of dislocation is called the fault-plane: not a plane in the mathe matical sense, since the surface is always found to be irregular and curved on being traced for any distance. The general inclination of this plane to the horizontal is the dip of the fault ; to the vertical the hade; where the fault is vertical there is no dip or hade. The amount of vertical displacement is the throw : of the lateral dis placement, the heave. In a gently inclined fault the heave will be great for even a small throw. The downthrow or downcast side of a fault is that side where the strata have moved relatively down wards: the other side is the upthrow or upcast. Faults, especially minor dislocations, run in any direction, but they are frequently found to coincide with the directions of dip and strike of stratified rocks and so to have a causal connection with systems of folding. Thus dip faults and strike faults arise. The effect of such faults on the outcrops of stratified rocks is shown in the diagrams.

Normal faults are those in which the fault plane is vertical, or inclined in such a manner that the downthrow is on the dip side of the fault plane. Reversed faults are those where the upthrow is on the dip side, so that one faulted block has been thrust upon the other. Transcurrent faults occur in regions of great folding, often extending for miles along the dip of the strata : there is no vertical, only horizontal movement.

Normal Faults'.—When two blocks of rock masses have moved relatively to one another, the fault plane is likely to have an irregular surface and its outcrop, or trace of the plane on the surface of the earth, will show minor departures from a straight line quite apart from the wider deviations due to topography. In 'The term "normal" is an old but convenient one for a certain class of fault. It is not necessarily the most widely distributed type.

places undisturbed rock may be found on either side, but generally there is a crushed and pulverized zone, with slickensiding, for inches or even several feet. Where this zone is composed of shattered rock debris it is known as fault breccia. Many metal liferous and mineral veins are dislocations filled with crystallized material. In an important fault, several types of rocks may occur on either side at different localities and the nature of the disloca tion will differ from place to place. Thus with hard rocks on either side there may be hardly any selvage ; passing through shales the fault may become a zone of contortion and slickensiding of con siderable width. In throw, faults vary from the merest slip to a movement of thousands of feet : in distance across country, from a few hundred feet to hundreds of miles. Often faults are found to pass into monoclinal folds, but as often they die out by gradu ally diminishing throw. Downwards, faulting must evidently dis appear when the zone of rock flowage is reached at some eight miles. When stratified rocks are traversed by a fault, the beds are often found to be bent on either side, as would be expected in rocks which could adjust themselves to slow ,movement by fold ing. Thus in a normal fault the beds bend downwards on the up throw and upwards on the downthrow : the opposite is the case in a reversed fault. Normally denudation planes down the surface equally on either side of a fault, but a resistant rock, abutting against much more easily denuded beds, may give rise to an unstanding ridge or face, a fault scarp.

Groups of Faults.—Small faults generally occur singly, but the more extensive dislocations are more often composed of a number of parallel dislocations running into each other to give the effect of a fault zone. A number of parallel faults with down throws in one direction give rise to step-faulting. Fault planes with the same strike but hading towards one another give rise to trough faults when one faults another : when hading away from one another, to ridge faults. Strike and dip faults of the same age rarely, if ever, cross one another, though they coalesce. When one fault crosses another and shifts it in the same way as a stratum is shifted in outcrop by a fault, the two faults belong to different periods, the shifted fault being obviously the older.

Reversed Faults.—These are almost always confined to highly folded and disturbed regions. Great masses of the earth's crust, as for example in the N.W. High lands of Scotland and in the Western Alps, have been thrust considerable distances over the underlying rocks : the dividing plane is a thrust plane. Crushed and shattered material in this plane is termed crush-breccia or crush-conglomerate.

Origin of Faults.—Faults are connected with horizontal move ments and folding of the earth's crust. During the formation of mountains of elevation the crust is bulged upwards and the rocks are subjected to great compression. Relief is effected partly by folding and partly by overthrusting: if shear takes place before overfolding reversed faulting obtains. Transcurrent faults signify the differential movements forward of parts of thrusts. Normal faults form at the conclusion of the great movement when the mass begins to settle down. Direct subsidence in uncrushed regions also gives rise to normal faulting. In the great majority of cases faults have been as slow in their making as folds, for great river systems have been undisturbed by faults of thousands of feet throw, as in the course of the Colorado River. Fault scarps are nearly always due to the juxtaposition of rocks of widely differing resistance to weathering. Occa sional cases occur, however, where ancient faults have increased their throw by sudden jumps at intervals, giving rise to earth quakes.