Fens

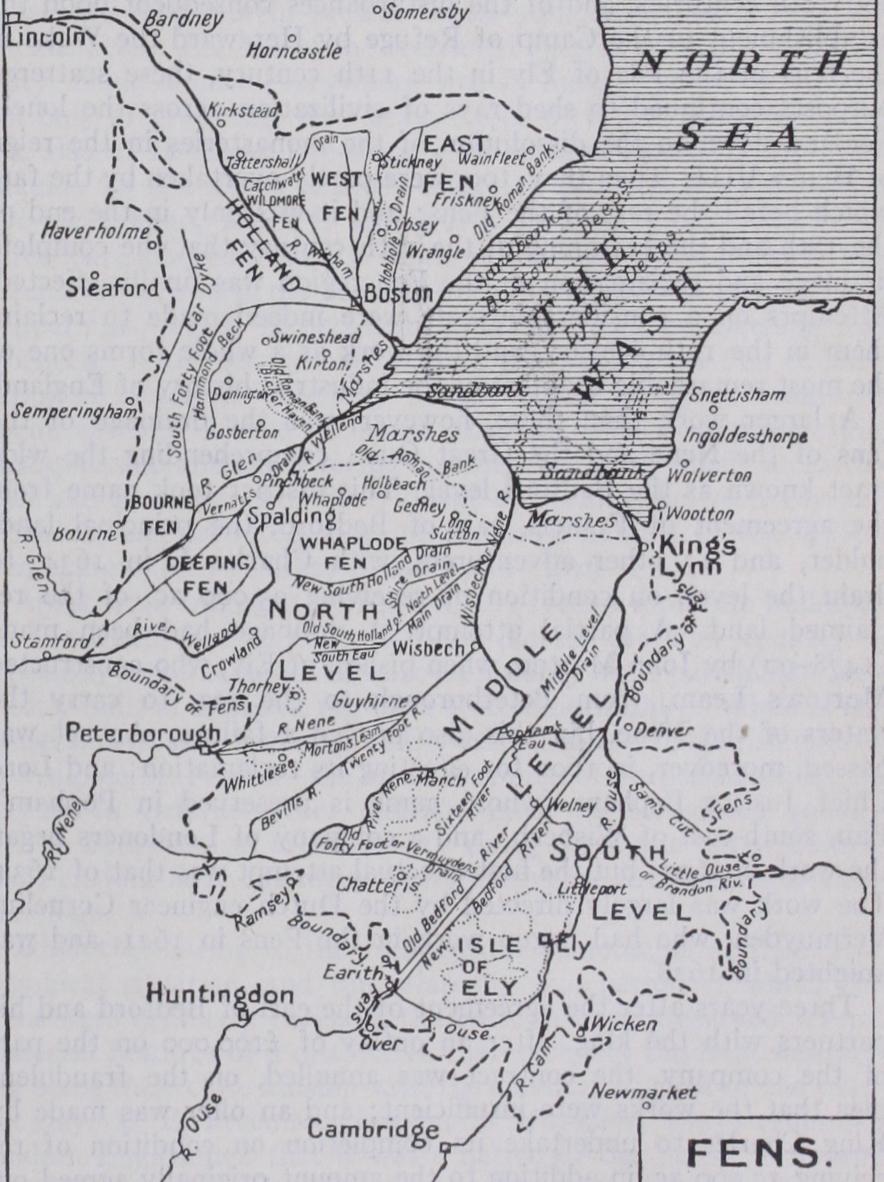

FENS, a district in the east of England, possessing a distinc tive history and peculiar characteristics. It lies west and south of the Wash, in Lincolnshire, Huntingdonshire, Cambridgeshire and Norfolk, and extends over more than 7o m. in length (Lincoln to Cambridge) and some 35 m. in maximum breadth (Stamford to Brandon in Suffolk), its area being considerably over half a million acres. Although low and flat, and seamed by innumerable water-courses, the entire region is not, as the Roman name of Metaris Aestuarium would imply, a river estuary, but a bay of the North sea, silted up, of which the Wash is the last remaining portion. Hydrographically, the Fens embrace the lower parts of the drainage-basins of the rivers Witham, Welland, Nene and Great Ouse ; and against these streams, as against the ocean, they are protected by earthen embankments, '0 to 15 ft. high. As a rule the drainage water is lifted off the Fens into the rivers by means of steam-pumps, formerly by windmills.

General History.

In very early days there is reason to be lieve that the whole fenland consisted of forest, but Sir Robert Cotton discovered at Conington in Lincolnshire the skeleton of a sea-fish lying six feet below the ground. (See Sir William Dug dale, History of Imbanking and Drainage, 1662.) Oak, ash, fir and nut trees, buried in the soil ; canoes and flat-bottomed rafts found several feet below the natural beds of rivers ; prehistoric beasts and reptiles dug up in a perfect state of preservation; all point to the existence of diverse forms of life before an historic period. Then came a great sea-quake which caused immense tidal waves to sweep over the area, transforming it into a vast lake. After a time the water did not flow wholly over the land as the muddiness of the stream produced a sandy settlement; silt formed and checked the usual flowing of the tides.

According to fairly credible tradition, the first systematic at tempt to drain the Fens was made by the Romans. They dug a catchwater drain (as the artificial fenland water-courses are called), the Caer or Car dyke, from Lincoln to Ramsey (or, ac cording to Stukeley, as far as Cambridge), along the western edge of the Fens, to carry off the precipitation of the higher districts which border the fenland, and constructed alongside the Welland and on the seashore earthen embankments, of which some 150 m.

survive. S. H. Miller is disposed to credit the native British in habitants of the Fens with having executed certain of these works. The Romans also carried causeways over the country. After their departure from Britain in the first half of the 5th century the Fens fell into neglect ; and despite the preservation of the woodlands for the purposes of the chase by the Norman and early Plantagenet kings, and the unsuccessful attempt which Richard de Rulos, chamberlain of William the Conqueror, made to drain Deeping fen, the fenland region became almost every where waterlogged, and relapsed to a great extent into a state of nature. In addition to this it was ravaged by serious inundations of the sea, for example, in the years 1178, 1248 (or 1250), 1288, 1322, 1467, 1571. Yet the fenland was not altogether a wilderness of reed-grown marsh and watery swamp. At various spots, more particularly in the north and in the south, there ex isted islands of firmer and higher ground, resting generally on the boulder clays of the Glacial epochs and on the inter-Glacial gravels of the Palaeolithic age. In these isolated localities members of the monastic orders (especially at a later date the Cistercians) began to settle after about the middle of the 7th century. At Medeshamp stead (i.e., Peterborough), Ely, Crowland, Ramsey, Thorney, Spalding, Peakirk, Swineshead, Tattershall, Kirkstead, Bardney, Sempringham, Bourne and numerous other places, they made settlements and built churches, monasteries and abbeys. In spite of the incursions of the predatory Northmen and Danes in the 9th and loth centuries, and of the disturbances consequent upon the establishment of the Camp of Refuge by Hereward the Wake in the fens of the Isle of Ely in the 11th century, these scattered outposts continued to shed rays of civilization across the lonely Fenland down to the dissolution of the monasteries in the reign of Henry VIII. Then they, too, were partly overtaken by the fate which befell the rest of the Fens ; and it was only in the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century that the complete drainage and reclamation of the Fen region was finally effected. Attempts on a considerable scale were indeed made to reclaim them in the 17th century, and the work as a whole forms one of the most remarkable chapters of the industrial history of England.

A larger work than these, however, was the drainage of the fens of the Nene and the Great Ouse, comprehending the wide tract known as the Bedford level. This district took name from the agreement of Francis, earl of Bedford, the principal land holder, and 13 other adventurers, with Charles I. in 1634, to drain the level, on condition of receivinT 95,000 ac. of the re claimed land. A partial attempt at drainage had been made (1478-90) by John Morton, when bishop of Ely, who constructed Morton's Leam, from Peterborough to the sea, to carry the waters of the Nene, but this also proved a failure. An act was passed, moreover, in 1602 for effecting its reclamation; and Lord Chief Justice Popham (whose name is preserved in Popham's Eau, south-east of Wisbech) and a company of Londoners began the work in 1605; but the first effectual attempt was that of The work was largely directed by the Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden, who had begun work in the Fens in 1621, and was knighted in 1628.

Three years after the agreement of the earl of Bedford and his partners with the king, after an outlay of II 00,00o on the part of the company, the contract was annulled, on the fraudulent plea that the works were insufficient; and an offer was made by King Charles to undertake its completion on condition of re ceiving 57,000 ac. in addition to the amount originally agreed on. This unjust attempt was frustrated by the breaking out of the civil war; and no further attempt at drainage was made until 1649, when the parliament reinstated the earl of Bedford's suc cessor in his father's rights. After an additional outlay of £300, 000, the adventurers received 95,000 ac. of reclaimed land, accord ing to the contract, which, however, fell far short of repaying the expense of the undertaking. In 1664 a royal charter was obtained to incorporate the company, which still exists, and carries on the concern under a governor, six bailiffs, 20 conservators, and a com monalty, each of whom must possess 10o ac. of land in the level, and has a voice in the election of officers. The conservators must each possess not less than 28o ac., the governor and bailiffs each 400 ac. The original adventurers had allotments of land according to their interest of the original 95,000 ac. ; but Charles II., on granting the charter, took care to secure to the crown a lot of 12,000 ac. out of the 95,000, which, however, is held under the directors, whereas the allotments are not held in common, though subject to the laws of the corporation. The level was divided in 1697 into three parts, called the North, Middle, and South levels —the second being separated from the others by the Nene and Old Bedford rivers.

These attempts failed owing to the determined opposition of the native fenmen ("stilt-walkers"), whom the drainage and appropriation of the unenclosed fenlands would deprive of valuable and long-enjoyed rights of commonage, turbary (turf-cutting), fishing, fowling, etc. Oliver Cromwell is said to have put him self at their head and succeeded in stopping all the operations. When he became Protector, however, he sanctioned Vermuyden's plans, and Scottish prisoners taken at Dunbar, and Dutch pris oners taken by Blake in his victory over Van Tromp, were employed as the workers. Vermuyden's system, however, was exclusively Dutch; and while perfectly suited to Holland it did not meet all the necessities of East Anglia. He confined his attention almost exclusively to the inland draining and embank ments, and did not provide sufficient outlet for the waters them selves into the sea.

Holland and other Fens on the west side of the Witham were finally drained in 1767, although not without much rioting and lawlessness ; and a striking account of the wonderful improve ments effected by a generation later is recorded in Arthur Young's General View of the Agriculture of the County of Lincoln (Lon don, 1799). The East, West and Wildmore fens on the east side of the Witham were drained in 1801-07 by John Rennie, who car ried off the precipitation which fell on the higher grounds by catch water drains, on the principle of the Roman Car dyke, and improved the outfall of the river, so that it might the more easily discharge the fen water which flowed or was pumped into it. The Welland or Deeping fens were drained in 1794, 18o1, 1824, 1837 and other years. Almost the only portion of the original wild Fens now remaining is Wicken fen, which lies east of the river Cam and south-east of the isle of Ely.

The Fen Rivers.

The preservation of the Fens depends in an intimate and essential manner upon the preservation of the rivers, and especially of their banks. The Witham, known origi nally as the Grant Avon, also called the Lindis by Leyland (Itinerary, vol. vii.), and in Jean Ingelow's High Tide on the Lincolnshire Coast, is some 8o m. long, and drains an area of 1,079 sq.m. It owes its present condition to engineering works carried out in the years 1762-64, 1865, 1881, and especially in 1880 84. In 1500 the river was dammed immediately above Boston by a large sluice, the effect of which was not only to hinder free navigation up to Lincoln (to which city sea-going vessels used to penetrate in the 14th and 15th centuries), but also to choke the channel below Boston with sedimentary matter. The sluice, or rather a new structure made in 1764-66, remains; but the river below Boston has been materially improved (188o-84), first by the construction of a new outfall, 3 m. in length, whereby the channel was not only straightened, but its current carried directly into deep water, without havifig to battle against the often shift ing sandbanks of the Wash; and secondly, by the deepening and regulation of the river-bed up to Boston. The Welland, which is about 7o m. long, and drains an area of 76o sq.m., was made to assume its present shape and direction in 1620, 1638, 165o, and 1835 and following years. The most radical alteration took place in 1794, when a new outfall was made from the con fluence of the Glen (3o m. long) to the Wash, a distance of nearly 3 m. The Nene, 90 m. long, and draining an area of some sq.m., was first regulated by Bishop Morton, and it was further improved in 1631, 1721, and especially, under plans by Rennie and Telford, in 1827-30 and 1832. The work done from 1721 onward consisted in straightening the lower reaches of the stream and in directing and deepening the outfall. The Ouse (q.v.) or Great Ouse, the largest of the fenland rivers, seems to have been deflected, at some unknown period, from a former channel connecting via the Old Croft river with the Nene, into the Little Ouse below Littleport ; and the courses of the two streams are now linked together by an elaborate network of artificial drains, the results of the great engineering works carried out in the Bed ford level in the 17th century. The old channel, starting from Earith, and known as the Old West water, carries only a small stream until, at a point above Ely, it joins the Cam. The salient features of the plan executed by Vermuyden for the earl of Bed ford in the years 1632-53 were as follows : taking the division of the area made in 1697-98 into (i.) the North level, between the river Welland and the river Nene; (ii.) the Middle level, be tween the Nene and the Old Bedford river (which was made at this time, i.e., 163o) ; and (iii.) the South level, from the Old Bedford river to the south-eastern border of the fenland. In the North level the Welland was embanked, the New South Eau, Peakirk drain, and Shire drain made, and the existing main drains deepened and regulated. In the Middle level the Nene was em banked from Peterborough to Guyhirn, also the Ouse from Earith to Over, both places at the south-west edge of the fenland; the New Bedford river was made from Earith to Denver, and the north side of the Old Bedford river and the south side of the New Bedford river were embanked, a long narrow "wash," or overflow basin, being left between them ; several large feeding drains were dug, including the Forty Foot or Vermuyden's drain, the Sixteen Foot river, Bevill's river, and the Twenty Foot river; and a new outfall was made for the Nene, and Denver sluice (to dam the old circuitous Ouse) constructed. In the South level Sam's cut was dug and the rivers were embanked. Since that period the mouth of the Ouse has been straightened above and below King's Lynn (1795-1821), a new straight cut made between Ely and Littleport, the North Level Main drain and the Middle Level drain constructed, and the meres of Ramsey, Whittlesey (1851-52), etc., drained and brought under cultivation. A con siderable barge traffic is maintained on the Ouse below St. Ives, on the Cam up to Cambridge, the Lark and Little Ouse, and the network of navigable cuts between the New Bedford river and Peterborough. The Nene, though locked up to Northampton, and connected from that point with the Grand Junction canal, is prac tically unused above Wansford, and traffic is small except below Wisbech.The effect of the drainage schemes has been to lower the level of the fenlands generally by some 18 in., owing to the shrinkage of the peat consequent upon the extraction of so much of its con tained water; and this again has tended, on the one hand, to diminish the speed and erosive power of the fenland rivers, and, or. the other, to choke up their respective outfalls with the sedi mentary matters which they themselves sluggishly roll seawards.

The Wash.

From this it will be plain that the Wash (q.v.) is being silted up by riverine detritus. The formation of new dry land, known at first as "marsh," goes on, however, but slowly. During the centuries since the Romans are believed to have con structed the sea-banks which shut out the ocean, it is computed that an area of not more than 6o,000 to 70,000 ac. has been won from the Wash, embanked, drained and brought more or less under cultivation. The greatest gain has been at the direct head of the bay, between the Welland and the Great Ouse, where the average annual accretion is estimated at to to 11 lineal feet. On the Lin colnshire coast, farther north, the average annual gain has been not quite 2 ft.; whilst on the opposite Norfolk coast it has been little more than 6 in. annually. On the whole, some 35,00o ac. were enclosed in the 17th century, about 19,00o ac. during the i8th, and about Io,000 ac. during the 19th century.Previous to the drainage of the Fens, ague, rheumatism and other ailments incidental to a damp climate were widely prevalent, but at the present day the Fen country is as healthy as the rest of England ; indeed, there is reason to believe that it is conducive to longevity.

Historical Notes.

The earliest inhabitants of this region of whom we have record were the British tribes of the Iceni con federation; the Romans, who subdued them, called them Coriceni or Coritani. In Saxon times the inhabitants of the Fens were known (e.g., to Bede) as Gyrvii, and are described as traversing the country on stilts. In the end of the i8th century those who dwelt in the remoter parts were scarcely more civilized, being known to their neighbours by the expressive term of "Slodgers." These rude fen-dwellers have in all ages been animated by a ten acious love of liberty. Boadicea, queen of the Iceni ; Hereward the Saxon, who defied William the Conqueror ; Cromwell and his Iron sides, are representative of the fenman's spirit at its best. The fen peasantry showed a stubborn defence of their rights, not only when they resisted the encroachments and selfish appropriations of the "adventurers" in the 17th century, but also in the Peasants' Rising of 1381, and in the Pilgrimage of Grace in the reign of Henry VIII. So long as the Fens were unenclosed and thickly studded with immense "forests" of reeds, and innumerable marshy pools and "rows" (channels connecting the pools), they abounded in wild fowl, being regularly frequented by various species of wild duck and geese, godwits, cranes, bitterns, herons, swans, ruffs and reeves. Vast numbers of these were taken in decoys (for descrip tions of these see Oldfield, Appendix, pp. 2-4, of A Topographical and Historical Account of Wainfleet [London, 1829] ; and Miller and Skertchly, The Fenland, pp. 369-375) and sent to the London markets. At the same time equally vast quantities of tame geese were reared in the Fens, and driven by road to London to be killed at Michaelmas. The waters, too, abounded in fresh-water fish, especially pike, perch, bream, tench, rud, dace, roach, eels and sticklebacks. The soil of the reclaimed Fens is of exceptional fer tility, being almost everywhere rich in humus, which is capable not only of producing very heavy crops of wheat and other corn, but also of fattening live-stock with peculiar ease. Of the crops peculiar to the region it must suffice to mention the old British dye-plant woad, which is still grown on a small scale in two or three parishes immediately south of Boston; hemp, which was extensively grown in the i8th century, but is not now planted ; and peppermint, which is occasionally grown, e.g., at Deeping and Wisbech. In the second half of the 19th century the Fen country acquired a certain celebrity in the world of sport from the encouragement it gave to speed skating. Whenever practicable, championship and other racing meetings are held, chiefly at Little port and Spalding. The little village of Welney, between Ely and Wisbech, has produced some of the most notable of the typical Fen skaters, e.g., "Turkey" Smart and "Fish" Smart.Apart from fragmentary ruins of the former monastic buildings of Crowland, Kirkstead and other places, the Fen country is especially remarkable for the size and beauty of its parish churches, mostly built of Barnack rag from Northamptonshire. While in the possession of such buildings as Ely cathedral and the parish church of Walpole St. Peter's—the finest specimen of Perpendicular archi tecture in Britain—other districts must be considered equally rich in ecclesiastical architecture. Using these fine opportunities, the Fen folk have for many years cultivated the science of cam panology.

Dialect.

Owing to the comparative remoteness of their geo graphical situation, and the relatively late period at which the Fens were definitely enclosed, the Fenmen have preserved several dialectal features of a distinctive character, not the least interest ing being their close kinship with the classical English of the pres ent day. E. E. Freeman (Longman's Magazine, 1875) reminded modern Englishmen that it was a native of the Fens, "a Bourne man, who gave the English language its present shape." This was Robert Manning, or Robert of Brunne, who in or about 1303 wrote The Handlynge Synne.