Fifth Monarchy Men

FIFTH MONARCHY MEN, the name of a Puritan sect in England which for a time supported the 'government of Oliver Cromwell in the belief that it was a preparation for the "fifth monarchy," that is for the monarchy which should succeed the Assyrian, the Persian, the Greek and the Roman, and during which Christ should reign on earth with His saints for a thousand years. Disappointed in their hopes they agitated against the government and Cromwell ; but the arrest of their leaders and preachers, Christopher Feake, John Rogers and others, cooled their ardour. After the Restoration, on Jan. 6, 1661, a band of Fifth Monarchy men, headed by a cooper named Thomas Venner, who was one of their preachers, made an attempt to obtain pos session of London. Venner and ten others were executed and from that time the special doctrines of the sect died out.

For an account of the rising of 166i see Sir John Reresby, Memoirs, 1634-1689, edited by J. J. Cartwright (1875) ; and for the proceedings of the sect see S. R. Gardiner, History of the Commonwealth and Protectorate, passim (1894-19o1).

FIG,

the popular name given to various plants of the genus Fig, the popular name given to various plants of the genus Ficus, of the mulberry family (Moraceae), comprising about 800 species which are characterized by a remarkable development of the pear-shaped fruiting receptacle, the edge of which curves in wards, so as to form a nearly closed cavity, bearing the numerous fertile and sterile flowers mingled on its surface. The species vary greatly in habit,—some being low trailing shrubs, others gigantic trees, among the most striking forms of the tropical forests to which they are chiefly indigenous. They have alternate leaves, and abound in a milky juice, usually acrid, though in a few in stances sufficiently mild to be used for allaying thirst. This juice contains caoutchouc in large quantity.

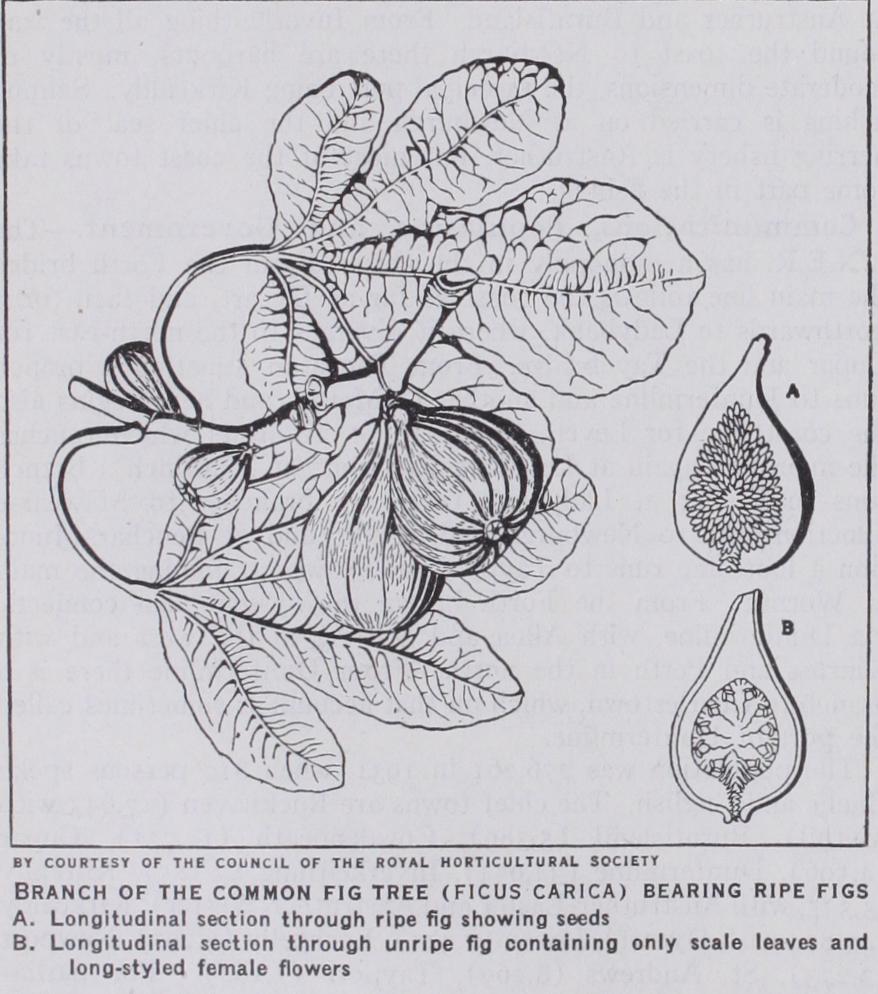

Ficus Carica (see fig.), which yields the well-known figs of commerce, is a bush or small tree—rarely more than 18 or 20 ft. high—with broad, rough, deciduous leaves, deeply lobed in the cultivated varieties, but in the wild plant sometimes nearly entire.

The green, rough branches bear the solitary, nearly sessile recep tacles in the axils of the leaves. The male flowers are chiefly in the upper part of the cavity, and in most varieties are few in number. As it ripens, the receptacle enlarges greatly, and the numerous single-seeded pericarps or true fruits become imbedded in it. The fruit of the wild fig never acquires the succulence of the cultivated kinds. The fig seems to be indigenous to Asia Minor and Syria, but now occurs wild in most of the Mediterranean countries.

From the ease with which the nutritious fruit can be preserved, it was probably one of the earliest objects of cultivation, as may be inferred from the frequent allusions to it in the Hebrew Scriptures. From a passage in Herodotus the fig would seem to have been unknown to the Persians in the days of the first Cyrus; but it must have spread in remote ages over all the districts around the Aegean and Levant. The Greeks are said to have received it from Caria (hence the specific name) ; but the fruit so improved under Hellenic culture that Attic figs became celebrated throughout the East, and, special laws were made to regulate their exportation. The fig was one of the principal articles of sustenance among the Greeks; the Spartans especially used it largely at their public tables. Pliny enumerates many varieties, and alludes to those from Ebusus (the modern Iviza) as most esteemed by Ro man epicures; while he describes those of home growth as furnish ing a large portion of the food of the slaves, particularly those em ployed in agriculture, by whom great quantities were eaten in the fresh state at the periods of fig-harvest. In Latin myths the plant plays an important part. Held sacred to Bacchus, it was employed in religious ceremonies; and the fig-tree that overshadowed the twin founders of Rome in the wolf's cave, as an emblem of the future prosperity of the race, testified to the high value set upon the fruit by the nations of antiquity.

The tree is now cultivated in all the Mediterranean countries, but the larger portion of the market supply of figs comes from Asia Minor, the Spanish Peninsula and the south of France. Those of Asiatic Turkey are considered the best. In the United States, with protection in winter, it succeeds as far north as Penn sylvania, and is grown commercially in several Southern and South-western States, but chiefly in California, Texas and Louis iana. Since about 1900 figs of Smyrna quality have been grown in California, whose total production of all dried and fresh figs in 1938 was about 44,00o tons. In Texas the same year about 1,240 tons of fresh figs were utilized in the commercial manu facture of preserves. The varieties are extremely numerous, and the fruit is of various colours, from deep purple to yellow, or nearly white. Many of the immature receptacles drop off owing to imperfect fertilization, which circumstance has led, from very ancient times, to the practice of caprification. Branches of the wild fig in flower are placed on the cultivated trees. Certain hy menopterous insects, of the genera Blastophaga and Sycophaga, which frequent the wild fig, enter the minute orifice of the recep tacle, apparently to deposit their eggs; conveying thus the pollen more completely to the stigmas, they ensure the fertilization and consequent ripening of the fruit. When ripe the figs are picked, and spread out to dry in the sun,—those of better quality being much pulled and extended by hand during the process. Thus pre pared, the fruit is packed closely in barrels, rush baskets or wooden boxes, for commerce. The best kind, known as elemi, are shipped at Smyrna, where the pulling and packing of figs form one of the most important industries of the people.

This fruit still constitutes a large part of the food of the natives of western Asia and southern Europe, both in the fresh and dried state. Alcohol is obtained from fermented figs in some southern countries; and a kind of wine, still made from the ripe fruit, was known to the ancients. Medicinally the fig is employed as a gentle laxative, when eaten abundantly often proving useful in chronic constipation. The wood is porous and of little value. The fig is grown for its fresh fruit (eaten as an article of dessert) in the milder parts of Europe ; and in the southern and south-western United States. The tree lives to a great age, and along the south ern coasts of England bears fruit abundantly as a standard ; but in Scotland and in many parts of England a south wall is indis pensable for its successful culti vation out of doors.

Fig trees are propagated by cuttings, which should be put into pots, and placed in a gentle hot bed. They may be obtained more speedily from layers, which should consist of two or three year old shoots, and these, when rooted, will form plants ready to bear fruit the first or second year after planting. The best soil for a fig border is a friable loam, not too rich, but well drained ; to correct the tendency to over-luxuriance of growth, the roots should be confined within spaces surrounded by a wall enclosing an area of about a square yard. The fig tree naturally produces two sets of shoots and two crops of fruit in the season. The first shoots generally show young figs in July and August, but those in the climate of England seldom ripen, and should therefore be rubbed off. The late or midsummer shoots likewise put forth fruit-buds, which, however, do not develop fully till the following spring; and these form the only crop of figs on which the British gardener can depend.

The sycamore fig, F. Sycomorus, is a tree of large size, with heart-shaped leaves. From the deep shade cast by its spreading branches, it is a favourite tree in Egypt and Syria, being often planted along roads and near houses. It bears a sweet edible fruit, somewhat like that of the common fig, but produced in racemes on the older boughs. The apex of the fruit is sometimes removed, or an incision made in it, to induce earlier ripening.

The sacred fig, peepul or bo (F. religiosa), a large tree with heart-shaped, long-pointed leaves on slender footstalks, is much grown in southern Asia. The leaves are used for tanning, and afford lac, and a gum resembling caoutchouc is obtained from the juice; but in India it is chiefly planted with a religious object, being regarded as sacred by both Brahmans and Buddhists. A gigantic bo, growing near Anarajapoora, in Ceylon, is, if tradition may be trusted, one of the oldest trees in the world. It is said to have been a branch of the tree under which Gautama Buddha be came endued with his divine powers, and has always been held in the greatest veneration.

Ficus elastica, the india-rubber tree, the large, oblong-shaped, glossy leaves, and pink buds of which are so familiar in our greenhouses, furnished previous to the cultivation of South Amer ican rubber trees in the Orient, most of the caoutchouc obtained from the East Indies. It grows to a large size, and is remarkable for the snake-like roots that extend in contorted masses around the base of the trunk. The small fruit is unfit for food.

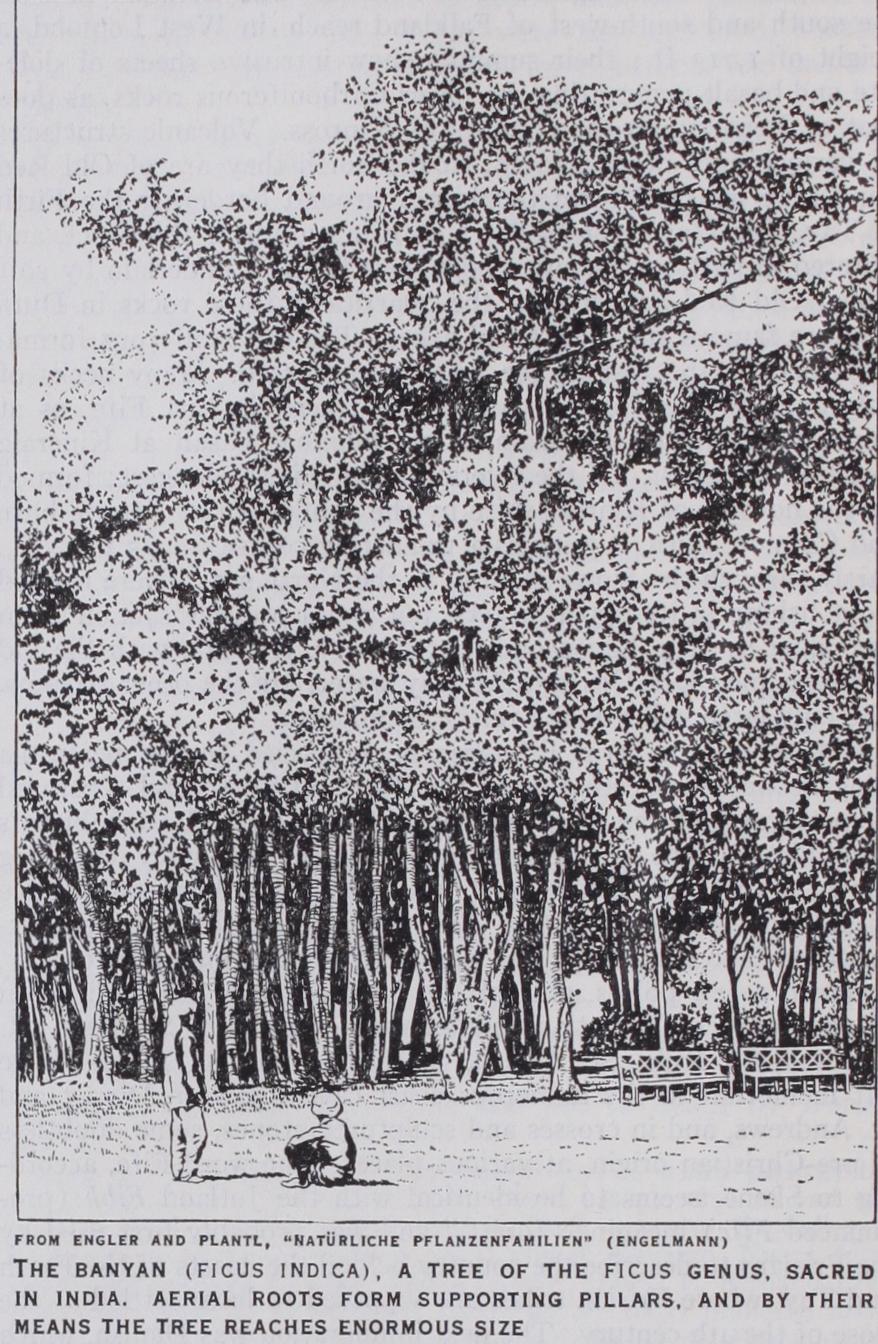

Ficus benghalensis, the banyan, wild in parts of northern India, but generally planted throughout the country, has a woody stem, branching to a height of 7o to loo ft. and of vast extent with heart-shaped entire leaves terminating in acute points. Every branch from the main body throws out its own roots, at first in small tender fibres, several yards from the ground; but these con tinually grow thicker until they reach the surface, when they strike in, increase to large trunks, and become parent trees, shooting out new branches from the top, which again in time suspend their roots, and these, swelling into trunks, produce other branches, the growth continuing as long as the earth contributes her sustenance. The tree usually grows from seeds dropped by birds on other trees. The leaf-axil of a palm forms a frequent receptacle for their growth, the palm becoming ultimately strangled by the growth of the fig, which by this time has developed numerous daughter stems which continue to expand and cover ultimately a large area. The famous tree in the Royal Botanic Gardens, Calcutta, began its growth at the end of the 18th century on a sacred date-palm. In 1907 it had nearly 250 aerial roots, the parent trunk was 42 ft. in girth, and its leafy crown had a circumference of 857 ft.; and it was still growing vigorously. Both this tree and F. religiosa cause destruction to buildings, especially in Bengal, from seeds dropped by birds germinating on the walls. The tree yields an inferior rubber, and a coarse rope is prepared from the bark and from the aerial roots.

In North America two native species occur, the golden fig (F. aurea) and the short-leaved fig (F. brevifolia), both found in southern Florida, while the common fig (F. Carica) is sparingly naturalized in old fields and along roadsides from Virginia to Florida, Tennessee and Texas. Numerous species are grown as greenhouse ornamentals.