Firebrick

FIREBRICK. Under this term are included all bricks, blocks and slabs used for lining furnaces, fire-mouths, flues, etc., where the brickwork has to withstand high temperature (see BRICK).

The conditions to which firebricks are subjected in use vary greatly as regards changes of temperature, crushing strain, corro sive action of gases, scouring action of fuel or furnace charge, chemical action of furnace charge and products of combustion, etc., and in order to meet these different conditions many varieties of firebricks are manufactured.

A firebrick suitable for ordinary purposes should be even and rather open in texture, fairly coarse in grain, free from cracks or warping, strong enough to withstand the pressure to which it may be subjected when in use, and sufficiently fired to ensure practi cally the full contraction of the material. Very few fireclays meet all these requirements, and it is usual to mix a certain proportion of ground firebrick, ganister, sand or clay with the fireclay before making up. The fireclay or shale or other materials are ground either between rollers or on perforated pans, and then passed through sieves to ensure a certain size and evenness of grain, after which the clay and other materials are mixed in suitable propor tion in the dry state, water being generally added in the mixing mill, and the bricks made up from plastic or semi-plastic clay in the ordinary way.

The proportion of ground firebrick, etc., used depends on the nature of the clay and the purpose for which the material is re quired, but generally speaking the more plastic clays require a higher percentage of broken firebrick or "grog" than the less plastic clays, the object being to produce a clay mixture which shall dry and fire without cracking, warping or excessive shrinkage, and which shall retain after 'firing a sufficiently open and even texture to withstand alternate heatings and coolings without cracking or flaking. For special purposes special mixtures are re quired and many expedients are used to obtain fireclay goods hav ing certain specific qualities. In preparing clay for the manu facture of ordinary fire-grate backs, etc., where the temperature is widely variable but never very high, a certain percentage of saw dust is often mixed with the fireclay, which burns out on firing and ensures a very open or porous texture. Such material is much less liable to splitting or flaking in use than one having a closer texture, but it is useless for furnace lining and similar work where strength and resistance to wear and tear are essential.

Furnace Firebrick.

For the construction of furnaces, fire mouths, etc., the firebrick used must be sufficiently strong and rigid to withstand the crushing strain of the superimposed work at the highest temperature to which the firebrick is subjected.The wearing out of a firebrick used in the construction of fur naces takes place in various ways according to the character of the brick and the particular conditions to which it i. subjected. The firebrick may waste by crumbling—due to excessive porosity or openness of texture ; it may waste by shattering ; it may gradually wear away by the friction of the descending charge in the furnace, of the solid particles carried by the flue gases and of the flue gases themselves ; it may waste by the gradual slagging of the surface through contact with fluxing materials ; in cases where it is sub jected to very high temperature it will gradually vitrify and con tract and so split and fall away from the setting. It is a well recognized fact that successive firings to a temperature approach ing the fusion point, or long continued heating near that tempera ture, will gradually produce vitrification, which brings about a very dense mass and close texture, and entirely alters the proper ties of the brick.

Where firebricks are in contact with the furnace charge it is necessary that the texture shall be fairly close, and that the chemical composition of the brick shall be such as to retard the formation of fusible double silicates as much as possible. Where the furnace charge is basic the firebrick should, generally speaking, be basic or aluminous and not siliceous, i.e., it should be made from a fireclay containing little free silica, or from such a fireclay to which a high percentage of alumina, lime, magnesia, or iron oxide has been added. For such purposes firebricks are often made from materials containing little or no clay, as for example mixtures of calcined and uncalcined magnesite ; mixtures of lime and mag nesia and their carbonates; mixtures of bauxite and clay; mix tures of bauxite, clay and pluinbago; bauxite and oxide of iron, etc.

In certain cases it is necessary to use an acid brick, and for the manufacture of these a high siliceous mineral, such as chert or ganister, is used, mixed if necessary with sufficient clay to bind the material together. Dinas fireclay, so-called, and the Banisters of the south Yorkshire coalfields are largely used for making these siliceous firebricks, which may be also used where the brickwork does not come in contact with basic material, as in the arches or other parts of many furnaces. It is evident that no particular kind of firebrick can be suitable for all purposes, and the manu facturer should endeavour to make his bricks of a definite corn position and texture to meet certain definite requirements, recog nizing that the materials at his disposal may be ill-adapted or entirely unsuitable for making firebricks for other purposes. In setting firebricks in position, a thin paste of fireclay and water or of material similar to that of which the brick is composed, must be used in place of ordinary mortar, and the joints should be as close as possible, only just sufficient of the paste being used to enable the bricks to "bed" on one another.

It has long been the practice on certain works to wash the face of firebrick work with a thin paste of some very refractory material—such as kaolin—in order to protect the firebricks from the direct action of the flue gases, and a thin paste of carborun dum and clay, or carborundum and silicate of soda has been ex tensively used for the same purpose. So-called carborundum bricks have been put on the market, which have a coating of car borundum and clay fired on to the firebrick, and which have a greatly extended life for certain purposes. It is probable that the carborundum gradually decomposes in the firing, leaving a thin coating of practically pure silica which forms a smooth, impervious and highly refractory facing. (X.) The classification of fireclay bricks used in America is as follows: high duty, fuses not lower than cone 31 (approximately 1,75o° C) ; intermediate duty, not lower than cone 28 (1,690° C) ; moderate duty, not lower than cone 26 (1,65o° C) ; low duty, not lower than cone 19 (1,510° C). The highest grade fireclay fuses at cone 35-36 (1,830-50° C). Bricks made from materials more refractory than fireclay are designated super-refractories.

Refractoriness.—The term firebrick intimates resistance to the softening effects of heat, but refractory brick is the better term. Firebricks must withstand metallurgical heats and resist the fusing action of slags. A silica brick is acid and is used in furnaces developing acid slags; lime, dolomite and magnesite (qq.v.), on the other hand, are strongly basic. Between these ex tremes every gradation occurs. A fireclay brick made from a siliceous clay is more or less acid, from pure clay slightly basic, from bauxite or diaspore (qq.v.) still more basic. Besides the basic and acid firebricks there are neutral bricks made from chrome ore. In an open hearth steel furnace, for example, the hearth may be built of dolomite or magnesite ; then at the slag line a band of neutral bricks is built, upon which rests the silica brick crown.

The best American fireclays,

et seq., quartzite, bauxite, dia spore, cyanite and all calcined materials are without plasticity and to make them into bricks some kind of bonding material is re quired. A plastic clay in quantity of io% and upward is most commonly employed to give the necessary plasticity, but in nu merous products it is not suitable, so lime, tar, powdered slags, such as glass and cement, silicate of soda and other chemicals are used. In the designation of siliceous bricks there is considerable confusion. Ganister, the English term for a clay bonded sandstone brick, in America is called quartzite and in Germany, Dinas. The lime bonded silica brick in England is the dinar brick and in America the silica brick.New Jersey, because of its fireclay deposits and its location on the early settled eastern coast, was the first locality in America to produce firebricks. It is said that a firebrick was produced in New Jersey as early as 1812, but there is no authentic record of this. In 1825 a factory was established in Woodbridge, N.J.; in Connecticut in 1835; in Pennsylvania in 1836 ; and in Maryland in 1839. The older grinding and pugging of hard materials with the wet-pan is being replaced by dry-pan grinding, and the wet pan is used only for pugging. Pug-mills as used in other clay industries are not commonly used for soft-mud firebricks.

Dry-pressed Firebricks.—In 1886 at Union Furnace, 0., firebricks of flint and plastic fireclays, and ganister rock, were made by the dry-press process (see BRICK), but because of the prejudice in favour of the hand-moulded product it was not com mercially successful. More recently the dry-press has been intro duced into many factories to supplement the soft-mud product and there are a number of factories that limit their product to the dry-press process. Because of the high pressure given to the material by the dry-press a manufacturer is enabled to make bricks from a non-plastic material such as flint clay, magnesite. etc., with less, and indeed often without any primary bonding material. The dry-press has been especially useful in the manu facture of magnesite bricks.

Stiff-mud Process.—Until recently, except in the manufacture of special shapes and, in one or two instances, a straight brrick product, the stiff-mud auger machine process (see BRICK) made no headway, but in 1928 a number of large firebrick factories were using this process. The clays are ground in a dry pan, pugged in a pug-mill, made into bricks through an auger machine, then re-pressed, dried in tunnel dryers, and finally burned in kilns, identically as in making other types of bricks.

Drying.—The early hot floors dryer consisted of a series of long covered ducts, each with a furnace at one end, connecting with a stack at the other end. This type of floor has given way to steam-heated concrete or iron floors, on the surface of which the brick are dried.

Burning.—The intermittent down-draft kiln is most widely used for burning firebrick. The round down-draft kiln is the favourite type and the more modern plants are so equipped. In 1928 the car-tunnel type was being widely adopted.

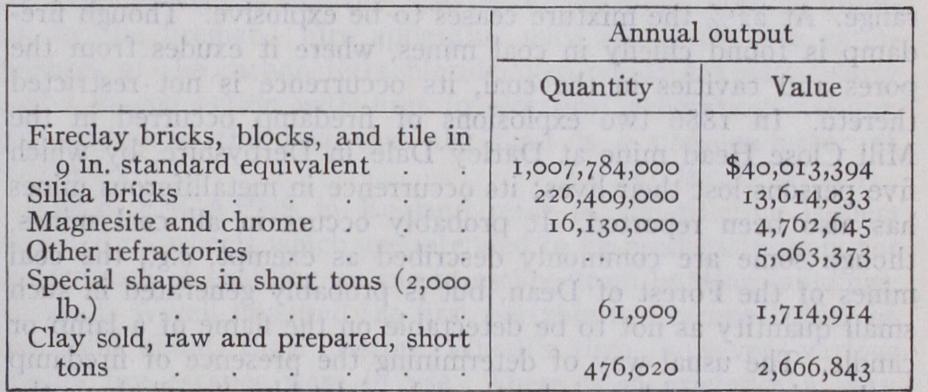

The latest Government bulletin (19 26) available gives the fol lowing statistics: (E. Lo.)