Flight Natural

FLIGHT (NATURAL). The flight of birds has been from time immemorial a riddle as well as a source of inspiration. The author of the Proverbs of Solomon describes "the way of an eagle in the air" as "too wonderful" for him; and for many cen turies the paradox that a bird could for hours together maintain its motion without a flap of the wing or any appreciable expendi ture of energy seemed hopeless of explanation. But though the upward gliding of a vulture until it is almost invisible, or the effortless sailing of an albatross for hundreds of miles over the ocean are obviously marvellous, the ordinary flapping flight of a swift or a pigeon is in reality almost as wonderful. For flapping flight involves a combination of a highly perfected mechanical design of the wings with a motive power of remarkable lightness; and, though men have carried on sailing flight in a motorless aeroplane for hours on end, a motor-driven flapping aeroplane has not been produced.

Gliding, Soaring or Sailing Flight.

For comprehension of the fundamental principles underlying non-flapping flight, we are indebted to the late Lord Rayleigh who in 1883 remarked that "wherever . . . a bird pursues his course for some time without working his wings we must conclude either (I) that the course is not horizontal, (2) that the wind is not horizontal, or (3) that the wind is not uniform." As we shall see these suggestions lead to the solution of the problem, which, as far as flight inland is concerned, may be exemplified by the behaviour of an ordinary vulture. He weighs about I olb., has wings each about 3f t. long and 'ft. wide, and, about an hour after sunrise, when he throws himself off the bough on which he has roosted, he gives the impression of being too heavily loaded for any but the clumsiest of flying. He flaps laboriously uphill, usually in a spiral path, until he has reached a height of 5o or I oof t. and then a mys terious change begins to show itself ; he flaps less and less hard and after a short time starts gliding steadily and majestically upwards in his spiral. After reaching a considerable height, which may be between Soo and 2,000f t., he has no need of further effort, and seems able to float at will in any direction and at any pace that he likes until he descends for food or because sunset is approaching.The details of his flight do not diminish our surprise ; for the air in the plains is often so still that there is no suggestion of an up-current sufficient to support a I olb. weight, and with the plane of his wings inclined upwards (the forward edge being higher than that in the rear) a vertical up-current would seem to drive him back ward, not forward. His continued advance seems inexplicable.

Downhill Gliding Through Still Air.

If a bird is gliding horizontally through still air the resistance of the air must lessen his speed, and on the other hand if he glides steeply downhill he will gain in speed. There must be some slope for which he will neither gain nor lose speed and its inclination is called the "angle of descent." Much detailed information has been accumulated regarding the forces which act on wings of various cross-sections and on elongated bodies when travelling at different speeds through the air (see AERONAUTICS) ; and if we have a wing 'of cross section AB (see fig. I) travelling in the direction X'OX the air-forces acting on it are equivalent to (I) a resistance or "drag" D backwards in the reversed direction of motion, (2) a lifting force L at right angles to the direction of motion. For a "high velocity" section, the ratio of L : D may reach 17. So when our bird is gliding steadily downhill along a line inclined and to the horizon it is acted on by D, L and its weight W, and we must have Now it may easily be calculated from well-known data that if we construct an artificial bird with rectangular wings of standard section and a torpedo-shaped body all of approximately the actual dimensions, the total weight being that of the bird, its angle of descent will be about 4° or 5°. Further, we habitually see birds in the tropics gliding at a considerable height in all directions without any obvious descent ; but we should not observe an angle of descent of 5° under these conditions, and for one who has been able to watch the gliding of kites from a hill it is impossible to believe that their angle of descent is as great as this. Hence, although past measurements of the forces acting upon stuffed birds in wind tunnels have indicated great inferiority by com parison with aerofoils fitted to torpedo-shaped bodies, the ratio of lift/drag in the stuffed birds not exceeding 5, the failure must be explained by the difficulty of preserving the true shape of the wing. Preliminary experiments made at S. Kensington have con firmed this view and from measurements made on living birds in 1920 in Africa, P. Idrac found a lift/drag ratio of about eighteen.

Gliding When There Is an Upward Current of Air.

If a bird whose angle of descent is I in 12 is gliding through still air at 18 miles an hour he will be descending at the rate of i or 1 miles an hour; and if there were a column of air ascending at over I2m. an hour the bird would climb as long as he kept within it in a spiral path.Now an ordinary observer has no evidence of such vertical air motion, for near the ground that motion must be negligible ; but there is complete proof, both meteorologically and by direct measurement, of its existence. We know that in sunny weather, owing to the overheating of air near the ground, conditions in continental regions in summer in medium latitudes and in the tropics for much of the year are unstable ; so that a mass of air rising above a heated rock will climb to a considerable height before it cools to the same temperature as the surrounding air and comes to rest. These local upward currents are experienced by meteorological kites and balloons, and their effects are described by aviators as "bumps" ; in Egypt, for instance, they extend to heights of 4,00o to r o,000 feet. In addition to large currents there are "small vertical currents" whose bottoms can in many cases be detected "in the vicinity of a town by kites or hawks soaring," and whose vertical speed over hilly country is probably as much as i 6f t. a second. The depend ence of soaring flight on vertical currents is also completely con firmed by the observations of Idrac in Senegal.

When a bird of prey is "stoop ing" at a great speed he bends his wing considerably at the el bow and wrist joints as shown at (a) in fig. 2 ; when he is gliding and not troubling about climbing the bending is slight as at (b) ; but when he is trying to ascend all he can he straightens his wings and spreads out the primary quills (the pinions at the ends of his wings) so that they are separate from each other over a length of about a fifth of the wing, as at (c). Nature obviously attaches some importance to this feature for she employs a special device to increase the separation beyond that due to the mere fan-like spreading of the feathers ; she deliberately leaves the primary quills of full width for about half their length and then steps down the width almost to half the previous amount for the outer half of the length of the quill. This feature, sometimes called the "notch" is apparently universal in birds of prey and the device, as a whole, strongly recalls the Handley-Page slotted wing which enables an aeroplane to climb at a much bigger angle of incidence. Thus G. T. Walker reports having seen vultures climbing on an upward cur rent of about r 2f t. a sec., their speed being about 2 5f t. a sec. up a slope of about 20°, the inclination of the wings also being 2o°. If in fig. 3 OP=25 represents the velocity of the bird in space, PN the vertical rate of climb is about 8.5 f.s., so that if QP= 12 represents the upward velocity of the air, the rate of climb through the ascending air is NQ = 3.5 f.s. and OQ, the bird's path relation to the air, descends at about 8.5°, so that the real angle of incidence POQ is about 28.5°. At first sight it would seem as if the bird could not possibly maintain its forward motion against the resistance of the air. But if we consider the forces act ing—the "lift" L (at right angles to the relative motion and so inclined forwards at 8.5° to the vertical) and the "drag" D—it is clear that the condition for maintenance of the forward mo tion is that the resultant of L and D shall be forward of the vertical, or that (since 8.5 ° = 7.7) the lift shall exceed 7.7 times the drag; this condition is satisfied with a Handley-Page wing.

When an aeroplane is losing pace the pilot is tempted to raise the nose of his machine so as to increase the angle of incidence of the wings and get an adequate lift ; but this process checks his pace, and if he is still losing height, it may be that no fur ther increase of the angle of incidence will support the aeroplane. The machine is thus said to "stall," control may be lost and a crash occur. Now at such times a Handley-Page slot is of great value in enabling control to be kept ; and as a bird trying to climb fast is probably near the stalling angle very often, the slotted ends of its wings have probably the great advantage of enabling it to maintain control. Vultures when climbing may occasionally be seen to make sudden movement of the wings which ends in a short downhill path and probably indicates recovery from a diffi cult situation of this kind.

Gliding (or Sailing) When the Wind Is Not Uniform.— Lord Rayleigh indicated in general terms the mechanism by which the energy necessary to maintain flight could be derived from the variability of the wind. He pointed out that it is the velocity of the bird relative to the air, not its velocity relative to the ground, which determines the forces acting on it ; and the bird can at any time by climbing upwards turn some of the energy of that relative velocity, with comparatively slight loss owing to air resistance, into energy of position ; conversely he can with little loss by gliding downhill turn energy of position into velocity relative to the air.

Now if the bird is flying horizontally with relative velocity U, the potential height to which he could climb is where g is the acceleration due to gravity; and if relative to the air he has an acceleration f in the direction of U, will after an extremely short interval T become (U and f and will so increase at a rate 2Uf ; hence the potential height will grow at a rate Uf/g. Also as the bird is moving horizontally L the "lift" must be equal to his weight ; and if the ratio L/D is k, D will be the weight divided by k ; so as the weight would produce a downward acceleration g, the backward acceleration due to the drag is g/k. Now if the wind is changing in any continuous man ner it will have some acceleration where the bird is, which we can call f', and by steering always so as to meet that acceleration he will secure an acceleration (f'—g/k) through the air and will gain potential height at a rate U(f'—g/k)/g or U(f'/g— r/k). If the bird does not fly directly against the direction of f' so that there is only a component —f" along his path, f" must replaFe f' in this formula.

Now it has long been known that the velocity of the wind is in general far from steady and much light has been gained regarding the gustiness due to eddymotion of the air under various condi tions. It has been estimated by Walker that in an ordinarily gusty wind of 2 2m. an hour the acceleration due to turbulence is in excess of 2 f ss. and for stronger winds proportionally higher. So for a bird with k= 12, whose angle of descent would be 5°, we must have f/g not less than or f not less than if, i.e., 2i. Thus a wind averaging 22X23=2, or, say, 3om. an hour would enable a bird to keep up its velocity without flapping.

It may be noted that not only do some inland birds of tem perate regions, such as rooks, and many sea-birds avail them selves of turbulence for sailing flight, but also tropical birds of prey who usually depend on convection currents. Thus on over cast days when there are not enough upward currents for kites and scavenger vultures to glide they usually remain in their trees; but occasionally a sudden change in the weather will them gliding in all directions as if aimlessly, or for pleasure ; and it would appear that turbulence afforded the explanation. Nonflapping flight is also possible when the wind, though steady, varies from place to place, as when a gull uses the screening of the wind by a vessel to describe circles near its stern.

The principle also has an important application to the gliding or sailing flight of albatrosses and other large sea birds in windy weather away from the influence of ships. It is known that the velocity of the wind must diminish down to the surface of the water owing to the influence of friction at the surface and of eddy motion in the air; so by rising or falling a bird can get into a stronger or weaker current of air. If then he sails uphill against the wind, the air that he meets will be at increasing heights and will have an increasing velocity in the direction opposite to his motion, so that his rate of travel through it will not diminish as it would if the air were stationary ; i.e., he will gain potential height. Exactly the same happens if he sails downhill with the wind, which is then decreasing in speed and has an acceleration in the direction opposite to his velocity. The natural way to com bine these effects is to describe circles in an inclined plane, always descending when moving to leeward and ascending when moving to windward. It is accordingly interesting that the results of a mission of Idrac to the south seas to study the problem entirely confirmed Rayleigh's ideas. He found (a) that such flight was only possible for very swift birds, the average speed of the albatross being 72 f.s. or 49 miles an hour; and (b) it needs a minimum wind of 17 f.s. close to the water.

Now the rate of increase of wind with height varies greatly with the conditions; and in the absence of detailed observations close to the surface of the sea we must utilize those over land made by the London Meteorological Office which agree with those at Nauen in giving an excess of 47% in the wind at so feet ( 5 metres) compared with that at 61 feet (2 metres) above ground. So corresponding to a speed of 24 f.s. at 7f t. we can deduce r, the velocity increase for 'ft. of height, as .26 f.s. Further, it seems that over the sea in high latitudes the reduction of the velocity will not extend so high as over land, and r will be greater. We shall not be very far wrong in taking it as •3 though Idrac's formula leads to only •2.

If the albatross climbs a slope of i in 3 at 72 f.s. against the wind his rate of ascent is 24 f.s., so that the increase of the wind in a second is 7.2 f.s. If for simplicity's sake we may treat U as constant in the computation, the rate of gain of potential height U (f/g—l/k) is i •6f t. if k= z 5; so he would in 2 seconds of either climb against, or descend with, the wind gain enough energy to take him 116 yards before further thought was neces sary. Of course, a greater rate of increase of wind with height, or a greater efficiency of design, would enlarge his powers, but a moderate rate would seem to give an albatross the ability to roam apparently at will. If he describes a circle inclined at with the lowest point to leeward and say 5f t. above the sea, while the highest point is 5oft. above sea, Walker's approximate formula gives a gain of potential height of i 3 f t. on describing the circle. Reference may also be made to a letter to Nature by S. L. Walkden.

Flapping Flight.

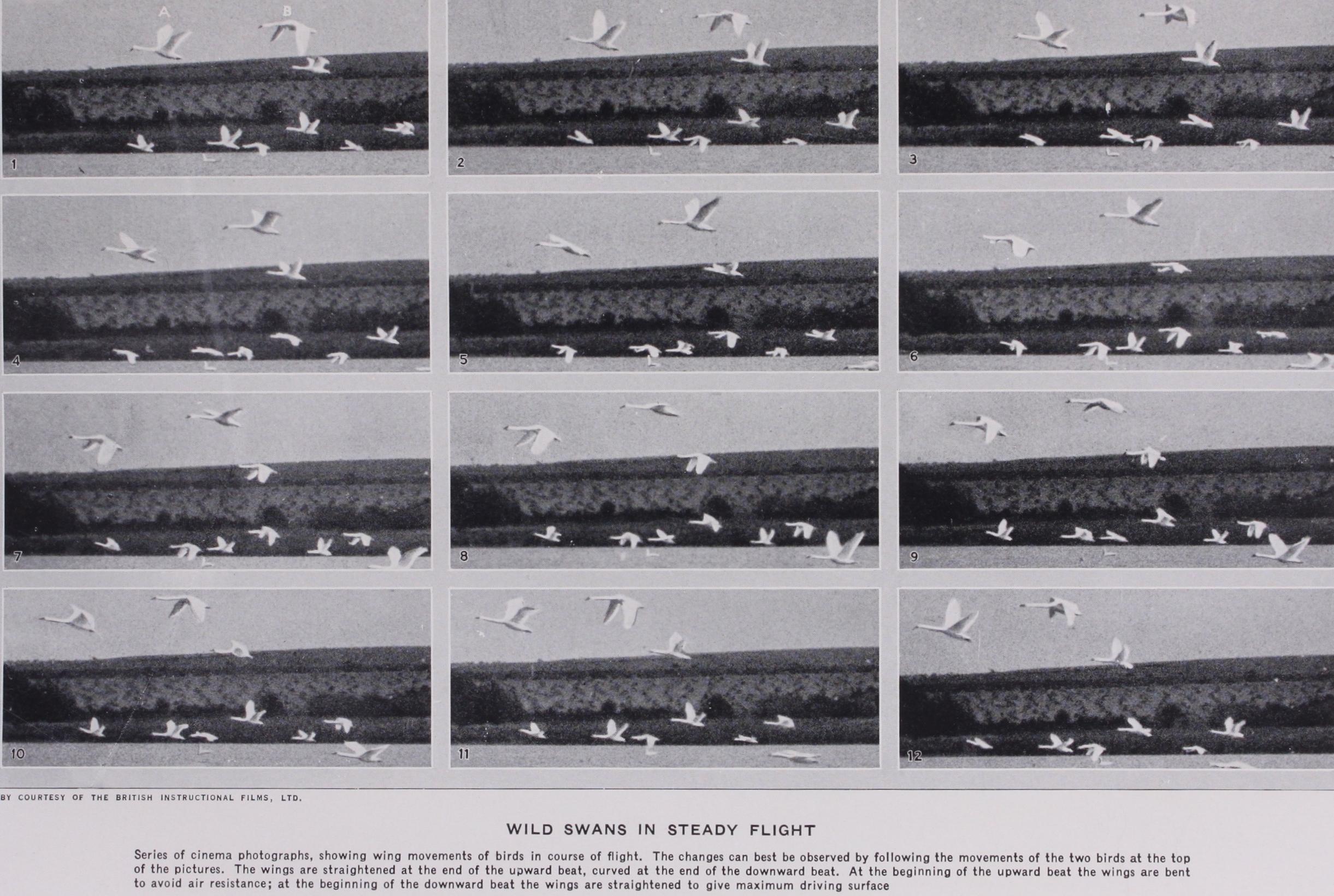

Birds differ materially in the details of their flapping, the contrasts between the deliberate beat of a heron, the smooth silent flight of an owl, and the hurried whirr of a partridge being conspicuous enough. But the general char acter of the wing movements is the same ; and as there have been differences of opinion, mainly owing to the difficulties of observa tion, regarding the fundamental facts, it will be useful to refer to the twelve reproductions in Plate I. of wild swans derived from a "slow-motion" cinema film made by British Instructional Films, Ltd. In Plate I., fig. i, the two top birds are marked (a) and (b), and in fig. 6 will be found diagrams (r) to (z 2) showing ap proximately the positions of the wings of bird (a) at instants corresponding with the figures of the plate. In them two features stand out prominently ; (a) the time interval between successive pictures being constant, the time of a down beat is half as long again as that of an upbeat ; and (b) though the wings are kept straight during positions 2-6 of a down beat, they are bent during 8–i i of the up-beat, the outer portions remaining almost at the same angle with the horizontal for the time 7-9, and being then lifted with a flick in the second half of the upbeat, 9–ii. As may be readily seen in Plate I., the motion of the wings relative to the body con sists of an up and down beat roughly in a vertical plane when the bird is in hori zontal steady flight. The rotation, or twisting of the wing about its own long axis also is of importance as it affects the angle of incidence, i.e., the angle between the direction of motion and the plane of the wing (between X'X and AB in fig. I). It will be seen from Pl. I., fig. 3 that while the wings of b, during an up beat, are inclined decidedly uphill, those of a, in a downbeat, are less clearly down hill; the same is true in figs. 6, 7 with a and b interchanged. If now the bird's body is describing from right to left an approxi mately straight line OQSU (fig. 7) a point in the outer portion of the wing will de scribe an undulating line OPQRSTU, with the upbeats steeper than the downbeats. So if we indicate the plane of the wing as shown in the film, clearly uphill at 0 and slightly downhill at Q, it will be seen that on the downbeat, as at Q, the angle of in cidence is positive and the lift L is up wards at right angles to the path ; while on the upbeat, as at S, the angle of inci dence is negative, so that L is downwards and forwards. The drag D is always backwards along the path.

It will be seen that the force L always tends to drive the bird forwards ; and as it is much greater than D which tends to retard the forward motion, the outer portion of the wing contributes propulsion. Also both L and D have a downward tendency during the upbeat, though the tendency is upward during the downbeat; so this portion of the wing is of little avail for support. With the inner portion, however, the situation is quite different. Here the slight up-and-down motion is almost cancelled by the slight down-and-up motion of the bird's body, so that the flight is essentially non-flapping ; the section of the wing must be adapted for high lift and the angle of in cidence is positive so that there is lift all the time.

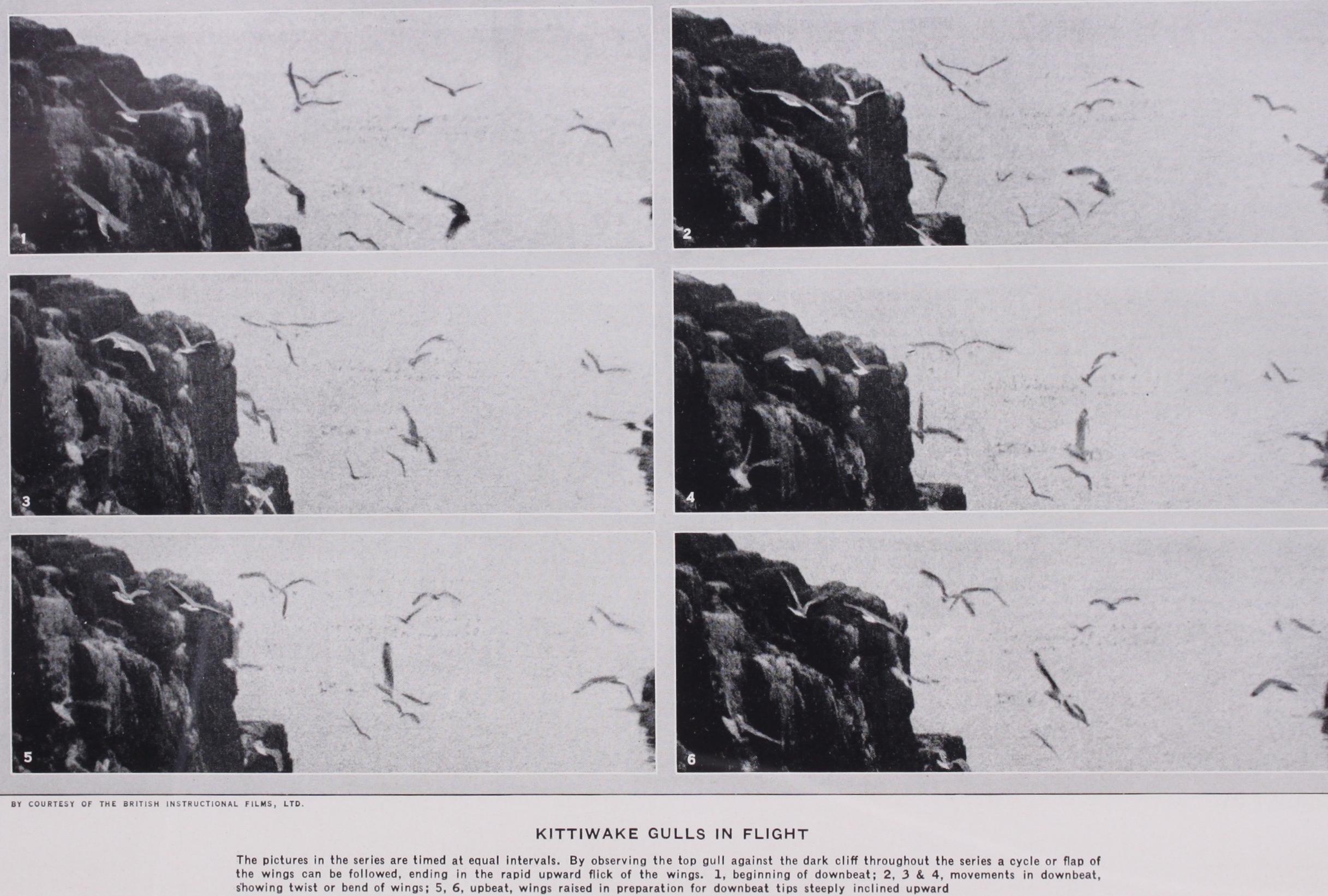

Reference to fig. 7 will show that the plane of the wing is twisted. Near the top of the up beat, when the upward flick of the outer portion occurs, the plane of the outer portion at B will be inclined more uphill than of the inner portion at B, but this is not so in the early portion of the upbeat at A and And during the downbeat the outer portions of the wing will be inclined downwards but not the inner portion. These inferences may be verified in the illustration of Plate II. of Kittiwake gulls. In figs. I, 2 of Pl. II., we have the downbeat of the marked bird with the downward inclined tips seen almost edge on. At the beginning of the upbeat in 15, the inner portions are inclined uphill more than the tips; but in 5, during the flick, the tips are inclined uphill more steeply than the inner portions.

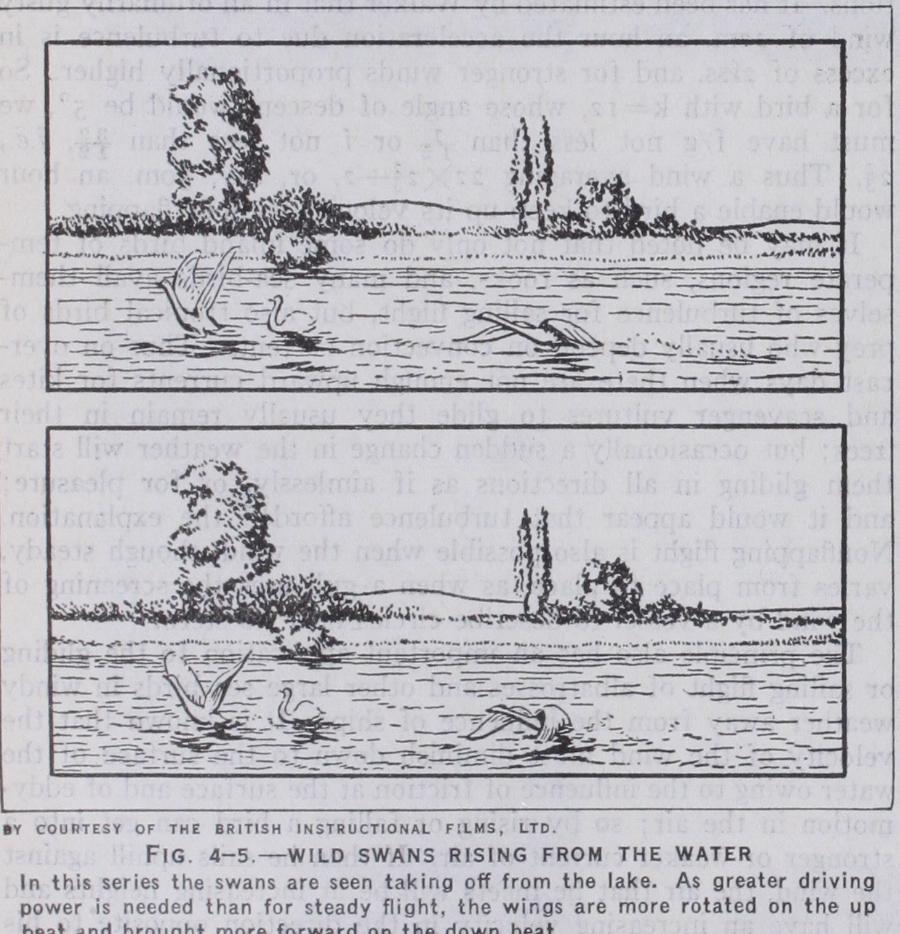

As will be seen from the reproductions, the swans (a) and (b) are ascending, so that their beats must be stronger than if they were flying horizontally; and it is worth while to see what modi fications occur when a bird has to exert all his force. In the figures 4-6 we have some wild swans flapping hard to get into the air, that to left in 4 beginning his downbeat; that to right is beginning his upbeat. They have not yet acquired much pace, and are using their feet as well as their wings. It will be seen in 5, that, as far as rotation is concerned, the plane of the wings of one is inclined downhill, while that of the other is uphill, and the reason is that, with a speed insufficient for the inner portion to support the weight by mere gliding, the bird has to adopt an uphill path and aim at more propulsion; so he uses most of the wing as he previously used only the outer portion, and with marked rotation of the type indicated in fig. 8. At the lowest point (sec fig. 5) the wings are rather forward, partly in order to avoid the water, but also in order to secure pro pulsion along a more upward direction.

The question naturally arises whether a machine fitted with aerofoils of known properties as wings attached to a torpedo shaped body would support and propel itself in the air if its dimensions and weight were those of a typical bird such as a rook; and the wings were flapped in approximately the same manner. To this Walker, as the result of an approxi mate computation with a "high lift" inner third of the wings for support and a flat outer third for propulsion, replies "Yes." He also finds that the power requisite compares not unfavourably with that necessary for a screw propeller driving a gliding bird with fixed wings.

Flight by Creatures Other Than Birds.-There is no evi dence of the use by these of principles other than those described; and it will therefore suffice to indicate the chief types :-Bats, Flying Lemurs, Flying Squirrels, Flying Phalangers; Pterodactyles (extinct), Flying Lizards (or Dragons), the Flying Snake of Borneo ; Flying-fishes, Flying-gurnards, American and African Fresh-water Flying-fishes; Insects.