Floral Envelopes

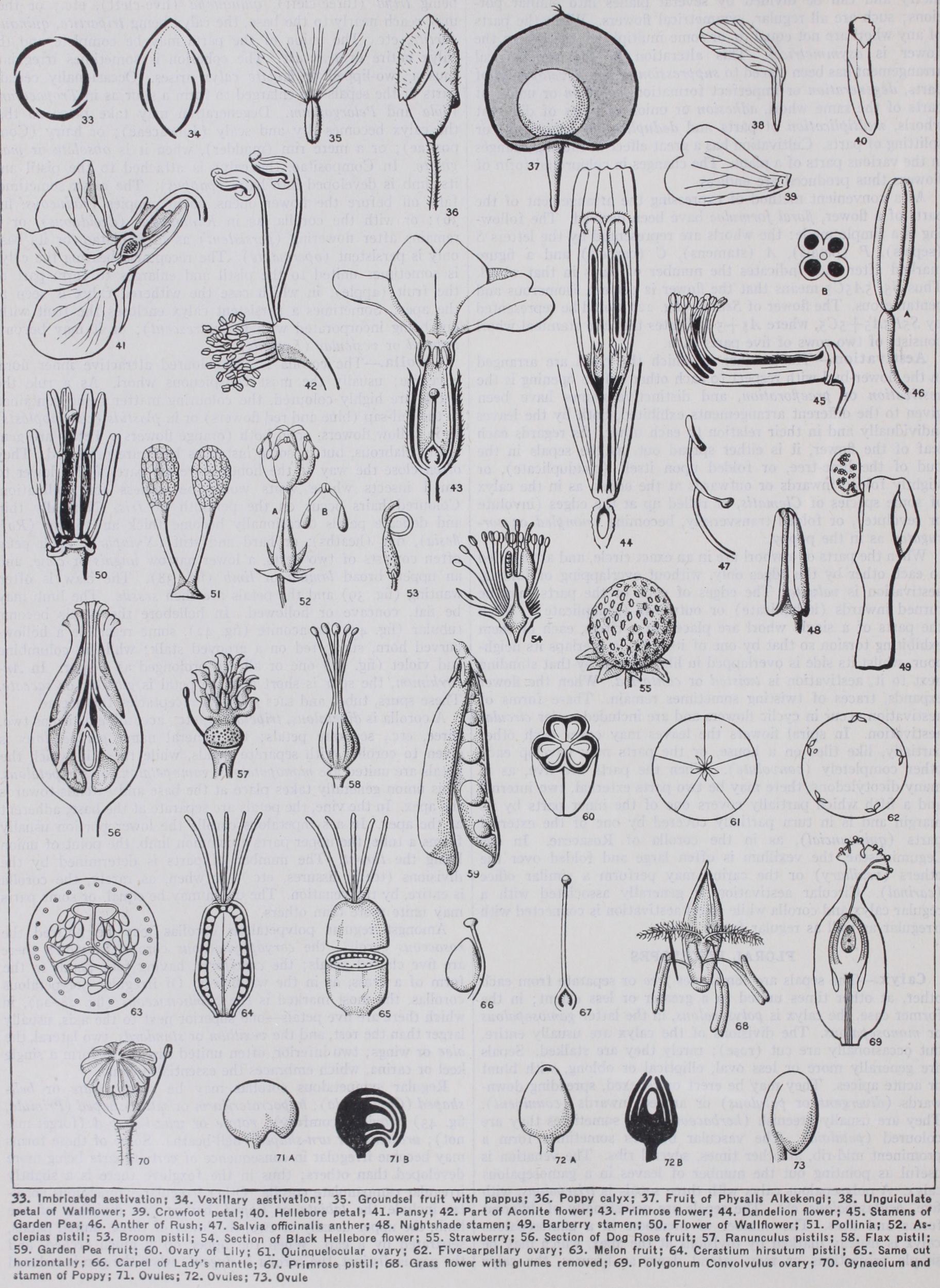

FLORAL ENVELOPES Calyx.—The sepals are sometimes free or separate from each other, at other times united to a greater or less extent; in the former case, the calyx is polysepalous, in the latter gamosepalous or monose palous. The divisions of the calyx are usually entire, but occasionally are cut (rose) ; rarely they are stalked. Sepals are generally more or less oval, elliptical or oblong, with blunt or acute apices. They may be erect or reflexed, spreading down wards (divergent or patulous) or arched inwards (connivent). They are usually greenish (herbaceous) but sometimes they are coloured (petaloid). The vascular bundles sometimes form a prominent midrib, at other times, several ribs. The venation is useful as pointing out the number of leaves in a gamosepalous calyx. A polysepalous calyx with three sepals is trisepalous, with five, pentasepalous, etc. The sepals are occasionally of different forms and sizes. The number of members in a gamosepalous calyx is usually marked by divisions at the apex, which may be simple projections or may extend down as fissures, the calyx being trifid (three-cleft), quinquefid (five-cleft), etc.; or they may reach nearly to the base, the calyx being tripartite, partite, etc. The union of the parts may be complete and the calyx entire or truncate. The cohesion is sometimes irregular; thus a two-lipped or labiate calyx arises. Occasionally certain parts of the sepals are enlarged to form a spur as in Tropaeolum, Viola and Pelargonium. Degeneration may take place so that the calyx becomes dry and scaly (Juncaceae) ; or hairy (Com positae) ; or a mere rim (madder), when it is obsolete or mar ginate. In Compositae, the calyx is attached to the pistil and its limb is developed into hairs (pappus) . The calyx sometimes falls off before the flower opens, as in poppies (caducous, fig. 36) ; or with the corolla, as in Ranunculus (deciduous), or it remains after flowering (persistent) as in Labiatae, or its base only is persistent (operculate). The receptacle bearing the calyx is sometimes united to the pistil and enlarges to form part of the fruit (apple), in which case the withered calyx is seen at the apex. Sometimes a persistent calyx encloses the fruit with out being incorporated with it (accrescent) ; or it may become inflated or vesicular (Lychnis).

Corolla.

The corolla is the coloured attractive inner floral envelope ; usually the most conspicuous whorl. As a rule the petals are highly coloured, the colouring matter being contained in the cell-sap (blue and red flowers) or in plastids (chromoplasts) as in yellow flowers, or in both (orange flowers). Petals are gen erally glabrous, but in some instances hairs are produced. They often close the way to the honey-secreting part of the flower to small insects whose visits would be useless for pollination. Coloured hairs occur on the perianth of Iris. Normally thin and delicate petals occasionally become thick and fleshy (Raf flesia), dry (heaths), or hard and stiff (Xylopia). Each petal often consists of two parts, a lower narrow unguis or claw, and an upper, broad lamina or limb (fig. 38). The claw is often wanting (fig. 39) and the petals are then sessile. The limb may be flat, concave or hollowed. In hellebore the petals become tubular (fig. 4o) ; in aconite (fig. 42), some resemble a hollow curved horn, supported on a grooved stalk; while in columbine and violet (fig. 41) one or all are prolonged as a spur. In An tirrhinum, the spur is short and the petal is gibbous or saccate. These spurs, tubes and sacs serve as receptacles for nectar.A corolla is dipetalous, tripetalous, etc., according as it has two, three, etc., separate petals; the general name polypetalous is given to corollas with separate petals, while those in which the petals are united are monopetalous, gamopetalous or sympetalous. This union generally takes place at the base and extends towards the apex. In the vine, the petals are separate at the base, adherent at the apex. In a sympetalous corolla the lower portion usually forms a tube, the upper parts a common limb, the point of union being the throat. The number of parts is determined by the divisions (teeth, fissures, etc.), or when, as rarely, the corolla is entire, by the venation. The union may be equal, or some parts may unite more than others.

Amongst regular polypetalous corollas may be noticed the rosaceous corolla; the caryophyllaceous corolla, in which there are five clawed petals ; the cruciform, having four petals in the form of a cross, as in the wallflower. Of irregular polypetalous corollas, the most marked is the papilionaceous (fig. 28-29), in which there are five petals—one superior next to the axis, usually larger than the rest, and the vexillum or standards, two lateral, the alae or wings; two inferior, often united slightly to form a single keel or carina, which embraces the essential organs.

Regular sympetalous corollas may be campanulate or bell shaped (Campanula) ; hypocrateriform or salver-shaped (Primula, fig. 43) tubular (comfrey) ; rotate or wheel-shaped (forget-me not) ; urceolate or urn-shaped (bell-heath). Some of these forms may become irregular in consequence of certain parts being more developed than others ; thus in the foxglove there is a slightly irregular campanulate corolla. Other irregular sympetalous corol las include the labiate or lipped, having two divisions of the limb, the upper usually of two, the lower of three, united petals, separated by a gap. When the upper lip is much arched, and the gap is distinct, the corolla is ringent; when the gap is reduced to a chink, as in snapdragon, personate. In Calceolaria the lips become much hollowed out. When a tubular corolla is split to form a strap-like process on one side, it is ligulate or strap shaped (fig. 44), as in many Compositae.

Petals are sometimes suppressed and at times the whole corolla is absent. In Amorpha there is only a single petal. In the Ranunculaceae some genera (e.g., Ranunculus) have both calyx and corolla, while others (e.g., Anemone) have only a coloured calyx.

The term nectary includes those parts of a flower which secrete a honey-like substance, as the glandular depression on the petal of Ranunculus (fig. 39). The honey attracts insects, which convey pollen to the stigma. The horn-like nectaries under the galeate sepal of Aconitum (fig. 42) are modified petals, as are the tubular nectaries of hellebore (fig. 54).

Petals are attached to the axis usually by a narrow base. When this attachment is by an articulation, the petals fall off either immediately after expansion (caducous) or after fertilisation (deciduous). A corolla continuous with axis, as in Campanula, may remain in a withered state while the fruit is ripening. A sympetalous corolla falls off in one piece.

As a stamen represents a leaf developed to bear pollen or microspores, it is spoken of in comparative morphology as a microsporophyll; similarly the carpels which make up the pistil are the megasporophylls (see ANGIOSPERMS). In plants with hermaphrodite flowers, self-fertilisation is often provided against by the structure of the parts or by the period of ripening of the organs. For instance, in Primula (fig. 43), some flowers (thrum eyed) have long stamens and a short styled pistil, others (pin eyed) short stamens and a long-styled pistil; these are dimorphic. In some plants the stamens are perfected before the pistil (proton derous) ; more rarely, the pistil is perfected first (protogynous). Plants in which protandry or protogyny occur are dichogamous. When the same plant bears unisexual flowers of both sexes it is monoecious (hazel) ; when the male and female flowers are on separate plants, the plant is dioecious (hemp) ; when there are male, female and hermaphrodite flowers, it is polygamous.

Stamens.

The stamens arise from the receptacle within the petals, with which they generally alternate, forming one or more whorls, collectively constituting the androecium. Their normal position is below the pistil (inferior), but they may be above (superior) or, as in Saxifragaceae, half inferior or half superior. Sometimes they adhere to the petals (epitalous), or to the pistil, so as to form a column (gynandrous). These arrangements are important in classification. Stamens vary in number from one to many, even hundreds. In acyclic flowers there is often a gradual transition from petals to stamens, as in the white water lily (fig. 21) . When there is only one whorl the stamens are usually equal in number to the sepals or petals. The additional rows of stamens may be developed in centripetal order or interposed be tween the pre-existing ones or placed outside them, i.e., be de veloped centrifugally (geranium). When the stamens are fewer than 20, they are definite; when more, indefinite, represented by the symbol oo. A flower with one stamen is monandrous, with two, diandrous, with many, polyandrous, etc.The function of the stamen is the development and distribution of the pollen, which is contained in the anther. If the latter is absent, the stamen cannot perform its functions. The anther is developed before the filament, which may be absent (e.g., mistle toe), when the anther is sessile.

The Filament.—The filament is usually thread-like and cylin drical, or slightly tapering towards its summit. It may, however, be thickened and flattened in various ways. The length sometimes bears a relation to that of the pistil, and to the position of the flower. Though usually of sufficient solidarity to support the anther in an erect position, the filament is sometimes (e.g., grasses) delicate and hair-like, so that the anther is pendulous (fig. 68). It is generally continuous, but sometimes is bent or jointed (geniculate), or spiral (e.g., pellitory). In Fuchsia it is red, in Adamia, blue; in Ranunculus acris, yellow. The filament is usually articulated to the receptacle and the stamen falls off after fertilisation, but in Campanula, the stamens remain in a withered state. The filaments may cohere to a greater or lesser extent, the anthers remaining free. Thus, all the filaments may unite to form a tube round the pistil (e.g., mallow), the stamens being monadelphous, or they may be arranged in two bundles (diadelphous), as in the pea, where nine out of ten unite, the posterior one being free (fig. 45) . In this case the stamens, originally free, cohere, but in most cases each bundle arises from the branching of a single stamen.

The Anther.—The anther consists of lobes containing the minute pollen grains, which, when mature, are discharged by an opening. There is a double covering to the anther—the outer exothecium resembling the epidermis and of ten bearing stomata; the inner endothecium formed by a layer or layers of cellular tissue, the cells of which have thickened walls. The endothecium generally becomes thinner towards the part where the anther opens out, and there disappears. The anther appears first as a simple papilla of meristem, upon which indications of two lobes soon appear. Upon these projections rudiments of the pollen sacs, usually four, two on each lobe, are seen. In each differ entiation takes place in the layers beneath the epidermis, by which an outer small-celled layer surrounds an inner one of larger cells. These central cells are the pollen mother-cells, the outer cells forming the endothecium while the exothecium arises from the epidermis.

When all four pollen-sacs remain permanently the anther is quadrilocular (fig. 46) . Sometimes, however, the sacs in each lobe unite to give a bilocular anther. Further fusion of the lobes or the abortion of one of them (e.g., hollyhock) leads to a uni locular anther. Occasionally there are numerous cavities in the anther (e.g., mistletoe). The lobes are generally more or less oval or elliptical. The division between them is marked on the face of the anther by a furrow, and there is usually a suture indi cating the line of dehiscence. Stamens may cohere by their anthers becoming syngenesious (e.g., Compositae).

The Connective.—The anther-lobes are united by the con nective which is either continuous with the filament or articulated with it. When the filament is continuous and prolonged so that the lobes appear to be united throughout their length, the anther is adnate or adherent. When the filament ends at the base of 'the anther, the latter is innate or erect. In these cases the anther is fixed. When, however, the attachment is narrow and an articulation exists, the anthers are movable (versatile) as in grasses (fig. 68). The connective is sometimes extended back wards and downwards (e.g., violet) to form a nectar-secreting spur.

Anther Dehiscence.—The opening or dehiscence of the anthers to discharge their content takes place by clefts, valves or pores. When the anther-lobes are erect, the cleft is likewise along the line of suture—longitudinal dehiscence (fig. 16). In other in stances the opening is confined to the base or apex, each loculus opening by a single pore (e.g., Solanum, fig. 48) ; in the mistletoe there are numerous pores. In the barberry (fig. 49) each lobe opens by a valve on the outer side of the suture (valvular). Anthers dehisce at different periods during the process of flower ing, sometimes in the bud but more commonly when the flower is expanded. They may dehisce simultaneously or in succession. These variations are connected with the arrangements for the transference of pollen. Introrse anthers dehisce by the surface next the centre of the flower, extrorse anthers by the outer surface; when by the sides (e.g., Iris) they are laterally dehiscent.

Stamens occasionally become sterile by non-development of the anthers and are then called staminodes. Some stamens are enclosed within the tube of the flower (included) others are ex serted, i.e., extend beyond the flower (e.g., Plantago) ; some times they are exserted in early growth, but become included later (e.g., Geranium striatum). When there is more than one whorl, the stamens on the outside are often longest (e.g., many Rosa ceae), but sometimes the reverse is the case. When the stamens are in two rows, those opposite the petals are usually the shorter. In some flowers the stamens are didynamous, only four out of five being developed and the upper pair longer than the lateral (e.g., Labiatae, Scrophulariaceae) . When there are six stamens, four may be long and two short (tetradynamous), alternating with the pairs of long ones (e.g., Cruciferae, fig. 5o).

Pollen.—The pollen-grains consist of small cells, developed from the large, thick-walled mother-cells in the interior of the pol len-sacs. A division takes place to form four cells in each mother cell and these are the pollen grains, which increase in size and acquire a cell-wall, differentiated into an outer cuticular extine and an inner intine. Then the walls of the mother-cells are ab sorbed and the grains float freely in the fluid of the pollen-sacs. The fluid gradually disappears and the mature grains form a powdery mass. In most Orchidaceae the pollen-grains are united into masses (pollinia, figs. 51, 52) by viscid matter. Each of these has a stalk (caudicle) which adheres to a prolongation at the base of the anther (rostellum) by a viscid gland (retinacu lum). Gynandrium is sometimes applied to the part of the column in orchids where the stamens are situated. The number of pollinia varies.

The extine is a firm membrane which defines the contour of the pollen-grain and gives it colour (generally yellow). The extine is either smooth or covered with projections and is often covered with viscid or oily matter. The intine is uniform, thin, transparent and extensible. In some aquatics (e.g., Zostera) only one covering exists.

Pollen-grains vary in diameter from o too in. or less. They are most commonly ellipsoidal, but may be spherical, cylindrical and curved, polyhedral (Compositae) or nearly tri angular in section. There are rounded pores varying from one to fifty, and through one or more of these the pollen-tube is extruded in germination. In monocotyledons there is usually only one, in dicotyledons, where they may form a circle round the equatorial surface, they number from three upwards. Within the pollen grain is granular protoplasm with oily particles and occasionally starch. Before leaving the pollen-sac, the grain divides into a vegetative cell or cells, from which the pollen-tube arises, and a generative cell, forming the male cells (see ANGIOSPERMS, GYM