Fluorescence and Phosphorescence

FLUORESCENCE AND PHOSPHORESCENCE, terms applied to the cases of emission of light, by illuminated sub stances, in which the emitted light is made up of colours not present in the illuminating radiation. The term phosphorescence is often used in general sense to denote the emission of light by living organisms, such as glow-worms, fire-flies, jelly fishes and deep sea fishes, and bacteria present in decaying matter. In these cases the phenomenon is the result of biochemical reactions, often, in the case of the higher organisms, under the control of the creature. We are not here concerned with phosphorescence in this sense (see PHOSPHORESCENCE, ANIMAL), but solely with the emis sion of light by bodies in which no chemical changes take place. and where illumination is a necessary preliminary. Substances which do not exhibit fluorescence or phosphorescence merely re flect or diffuse the light which falls upon them, coloured sub stances extracting certain constituents of the light by absorption and reflecting the residue, the absorbed radiations being trans formed into heat. We may regard white light as made up of a mixture of all possible colours, as this view, although perhaps not the most modern one, answers the purposes of the present case. A green pigment absorbs the red, orange, yellow, blue and violet constituents of the white light and diffuses the green rays. If il luminated by red or violet light, it appears black, as all of the light is absorbed. In the case of fluorescence and phosphorescence the absorbed rays, instead of being changed into heat, are trans formed into light of a different colour, which is emitted by the substance in addition to rays reflected or diffused in the usual manner. The substance may be regarded as a light "transformer," changing the wave-length of the rays, as the electrical trans former alters the voltage. Practically all substances exhibit the phenomenon to a greater or less degree, though it is usually masked by the faintness of the fluorescent or phosphorescent light in com parison with the light reflected or diffused. If only ultra-violet light, which the eye does not perceive directly, is used in a dark ened room for the illumination, the phenomenon is at once apparent, practically everything in the room becoming immediately more or less luminous.

The term fluorescence has been applied to the cases in which the emission of the light created, so to speak, within the substance continues only as long as the exciting rays fall upon it, while the term phosphorescence is used for cases in which the luminosity persists for a longer or shorter time, after the light has been shut off. Modern researches have shown, however, that this classi fication is unfortunate, for we can cause a fluorescent substance to become phosphorescent by altering the medium in which it is dissolved, e.g., by dissolving it in a gelatine solution and allowing the gelatine to dry. Moreover, many fluorescent substances, if examined by refined methods, are found to glow for a very brief interval of time, say —10,000 sec. after the illuminating light has been cut off. This circumstance has resulted in a tendency on the part of some writers to regard the two phenomena as identical. This, however, is not the case, for it has been fairly well established that fluorescence is a phenomenon which occurs wholly within the molecule, the re-emission of the light sometimes being delayed for a very brief interval, while true phosphorescence, which is in gen eral of much longer duration, results from the expulsion of an electron from the molecule, the phosphorescent light resulting from its return. These matters will be fully discussed later on.

History.

The phenomenon of phosphorescence was made the subject of scientific enquiry some 5o years before fluorescence was seriously investigated. The chapter opens with the discovery in 1602, by a cobbler of Bologna, Vincenzo Cascariolo, of a sub stance which shone brightly in the dark after exposure to a strong light. This shoemaker practised alchemy in his leisure moments, and having found on Mt. Pesara some fragments of a very heavy mineral which sparkled brilliantly in the sunlight, he took them home and heated them in his furnace in the hope of obtaining precious metals. The mineral was "heavy-spar," a natural sul phide of barium, and the result of his experiment was the birth of the celebrated "Bologna stone," the first of a series of so-called natural phosphors, the investigation of which at once became the fashion. These substances were usually porous in structure, and it was at first supposed that they soaked up light as a sponge soaks up water, but in 1652 Zecchi illuminated his phosphors with light of different colours and found that the colour of the phos phorescent light was the same in each case, thus proving that phosphorescence was not a re-emission of light stored up in the substance. This observation was confirmed and put on record by other observers, one of whom used coloured rays obtained from a prism for exciting the phosphorescence. This is of interest, as it was not until 200 years later that the discovery was made by Sir George Stokes that fluorescent bodies behaved in the same way.The study of fluorescence commenced about half a century after the discovery of the Bologna stone, though allusions to the phenomenon can be found as far back as the year 157o, when a Spanish physician, Niccolo Monardes, mentioned the blue-colour exhibited by a tincture of a certain wood (lignum nephriticum). Grimaldi in 1665 investigated the optical properties of this tinc ture, illuminating it in a darkened room with a beam of light concentrated by a lens, and described the blue luminosity of the cone of rays within the liquid. In i 7o4 Newton investigated the phenomenon, illuminating the solution with light of various colours, and attributing the effects observed to an internal reflec tion of the light. Nose in z 78o discovered the fluorescence of tincture of sandal wood and quassia. In 1792 an advance was made by Wunsch, who employed more or less homogeneous light obtained by a prism for the illumination. He described the effects observed, but was unable to explain them.

In a paper communicated to the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1833, Sir David Brewster described what he believed to be a new phenomenon to which he gave the name of "internal dis persion." By condensing sunlight with a lens on a bottle filled with a solution of chlorophyl, the green colouring matter of leaves, he observed that the path of the rays through the green liquid was marked by a cone of a blood red colour. He subse quently observed the same phenomenon in other liquids, and in some solids, notably fluor-spar, and named it "internal dispersion," being of the opinion that it was due to coloured particles held in suspension. Several years after Brewster's observations, Sir John Herschel discovered independently that a colourless solution of sulphate of quinine, when held in a strong light, showed a shim mer of blue at the surface at which the light entered. The illu minating beam, after its passage through the solution, was unable to provoke the blue colour in a second bottle of the liquid, though it was apparently unchanged either in colour or intensity. Herschel considered that the light had been modified in some new and mysterious manner at the surface of the liquid, and introduced the term "epipolized" (7reroXii, surface) to designate it. He con cluded that light which had once been epipolized, could not be epipolized a second time.

None of these early investigators had a glimmering of an idea that the phenomenon was an emission of a new set of radiations excited by the absorption of violet and ultra-violet rays. Newton and Wunsch were on the right track in their investigations with coloured light, and it is hard to see how they failed to find the key to the mystery. The latter investigator must have missed it by a very narrow margin, for the same method, in the hands of Sir G. G. Stokes, established the true nature of the phenomenon. His first paper "On the Change of Refrangibility of Light" was published in 1852. This brief title is a complete statement of the true nature of fluorescence. Extending the experiments of his predecessors he soon came to the conclusion that he was dealing with a wholly new phenomenon, the scattered beam of light differ ing in refrangibility (colour) from the rays which excited it. He at first spoke of it as "true internal dispersion" to distinguish it from the scattering of light by cloudy solutions which he called "false internal dispersion." He afterwards abandoned this term as misleading, substituting for it the term fluorescence (derived from fluor-spar, a mineral which exhibits the phenomenon), a term which does not presuppose any theory.

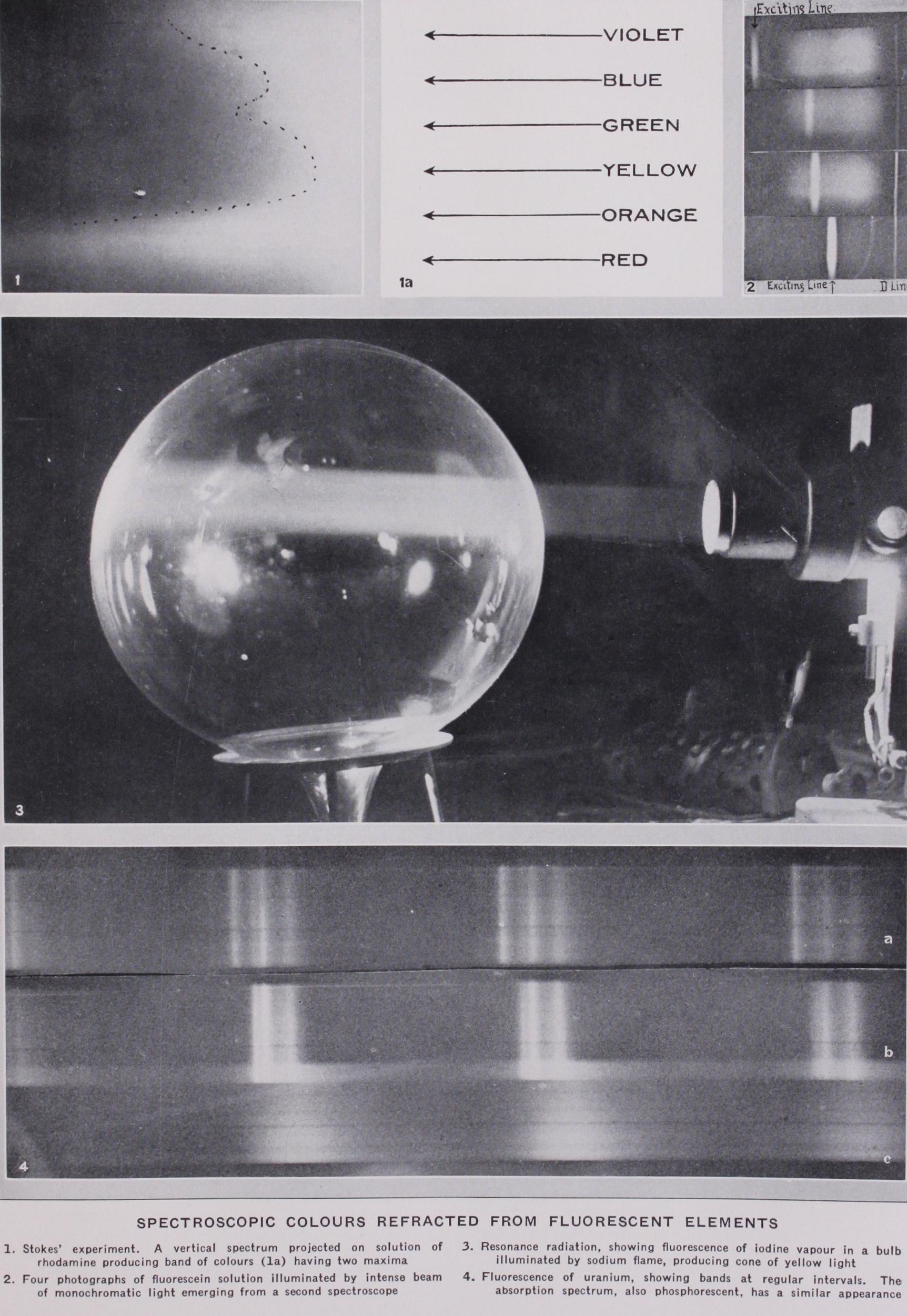

In one of Stokes's experiments a vertical spectrum was pro jected on the flat side of a glass tank filled with the solution, the fluorescence being observed through the side. Rays for which the absorption was slight penetrated the liquid to the opposite wall, and excited feeble fluorescence along their entire path. More powerfully absorbed rays penetrated to lesser and lesser dis tances, and excited fluorescence of increasing intensity, the gradual retreat of the fluorescence to the front wall being marked by a curved line. This line shows objectively the actual form of the absorption curve. The photograph (Plate I., fig. i) was made with a solution of rhodamine, the absorption band of which has two maxima as is clearly indicated. The position and colour of the exciting rays are indicated by arrows, and the absorption curve by dots.

Stokes's Law.

On exciting the fluorescence with monochro matic light, by restricting the excitation to a very narrow region of the spectrum passed through a fine slit, Stokes observed that the spectrum of the fluorescent light covered a fairly wide range in the blue region, which showed that light of many different shades of colour was produced by illumination with a single pure colour. Stokes was of the opinion that the fluorescent radiations were always of less refrangibility (longer wave-length) than the exciting rays, a condition governed by what has been known as Stokes's law, the validity of which was first called into question by Lommel.Many experimenters busied themselves with this question, and a controversy commenced which lasted for 20 years, Hagenbach and Lommel being the principal disputants, the former claiming that the law of Stokes was never violated, and that all of Lommel's results were due to the impurity of the light used for exciting the fluorescence. Lommel, however, excited the fluorescence of a solution of naphthalene red with the light of a sodium flame (which emits a nearly monochromatic yellow radiation) and ob served that the fluorescence spectrum extended from the red to the yellow-green region. In answer to objections by Hagenbach, he further showed that it was the yellow sodium light that was responsible for the green rays in the fluorescence, as the bunsen flame without the sodium caused no fluorescence at all. The more recent experiments of Nichols and Merritt, who measured with a photometer the intensity of the light at different points of the fluorescence spectrum, when excited by light of different colours, showed that Lommel was right and that Stokes's law did not hold in a number of cases. They found that the intensity curve of the fluorescent spectrum, by which we indicate the relative intensities of the different colours, was independent of the colour of the exciting light, though the total intensity varied over a wide range as the exciting wave-length was altered. They found, moreover, that the absorption band overlapped the fluorescent band in the case of all substances which showed violation of Stokes's law.

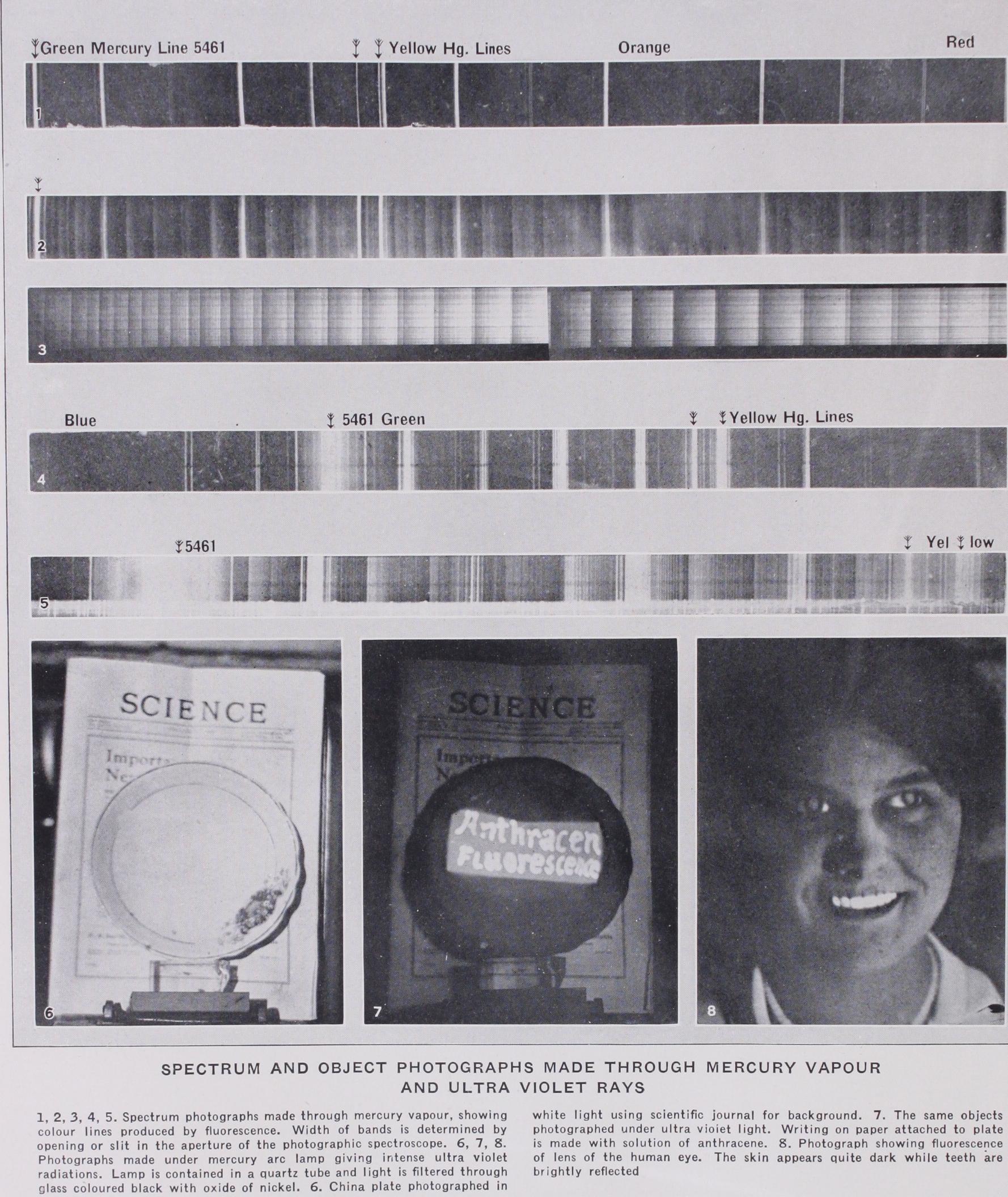

To show the failure of the law it is not necessary to resort to laborious measurements with the photometer. The spectrum pho tographs (Plate I., fig. 2) bring out the effect most conspicuous ly. They were made by directing the spectroscope at a small bottle filled with a dilute solution of fluorescein, which was illuminated with an intense beam of monochromatic light emerging from a second spectroscope, the eye piece of which had been replaced by a narrow slit. By turning the prism of this instrument, the colour of the exciting beam could be changed gradually from blue to green, and finally yellow. A suspension of fine particles in the fluorescein solution scattered a small amount of the exciting light, causing it to register its position in the spectrum with respect to the fluorescent spectrum. It appears in the photographs as a rather broad, hazy line, either immersed in the fluorescent band, or well outside of it, according to its colour. In the upper pic ture, the exciting light is entirely outside of the fluorescent range in the blue region; in the next two it has entered it, and in the fourth it has advanced so far towards the yellow that fluorescence is no longer produced. It is apparent from the two middle pic tures that the broad fluorescence band is fully developed on both sides of the exciting line. The colour of the fluorescence is yellow green. The faint line to the right of the fluorescence band is the D line of sodium, which was impressed on each plate to facilitate bringing them into coincidence.

Fluorescence of Gases and Vapours.

In spite of the very large amount of experimental work which had been done on fluorescence up to 1928, there was at that time no very satisfac tory theory of the phenomenon in the case of liquids and solids. In the case of gases and vapours, however, where the molecules are not under the influence of their neighbours, the mechanism of the transformation of the radiations was beginning to be eluci dated. The simplest case of all, involving no change of wave length or colour, is that in which the vapour absorbs one or more definite radiations and re-emits them without altering their fre quency. This is the phenomenon of resonance radiation, observed for the first time in the case of sodium vapour by R. W. Wood in 1905 (Phil. Mag., vol. xx.), and several years later in the case of mercury vapour. Though it is not strictly fluorescence, a brief consideration of the process involved will serve as a useful f oun dation upon which to build a discussion of the more complicated types. If a little metallic sodium is heated in a highly exhausted glass bulb to a temperature of r 40° C, and the yellow light from a small sodium flame is focussed at the centre of the bulb with a large condensing lens, the path of the rays through the vapour is marked by a cone of yellow light, the appearance being as if the bulb were filled with a light smoke or fog. (Plate I., fig. 3 gives a good idea of the phenomenon, though it shows the fluorescence of iodine instead of sodium vapour.) If, however, we substitute a source of light of any other colour for the sodium flame, we see nothing at all. The vapour is totally unable to scatter light unless its wave-length is precisely the wave-length of the so-called D lines of the solar spectrum, or the yellow light of the sodium flame.The process involved was formerly supposed to be analogous to what takes place when sound-waves from one tuning fork im pinge on a second fork of the same pitch, the latter absorbing some of the sound from the air, and being thrown into vibration itself in the process, so that if we quench the first fork with the fingers we hear the singing of the second. The modern theory, which we owe to Niels Bohr, is not quite so simple. By the ab sorption of the radiation the sodium atom is brought from its normal state, in which the electron revolves about the nucleus in an inner orbit, to an excited state in which the electron moves in an orbit more remote from the nucleus, the resonance radiation being emitted when the electron returns to its original orbit. (See AToM.) This makes the processes of absorption and re-emission successive instead of simultaneous as on the older theory. In the case of mercury vapour the same thing happens, except that it is an invisible radiation in the ultra-violet which is absorbed, and the mercury vapour is contained in an exhausted bulb of fused quartz, which requires no heating as the density of the vapour is great enough at room temperature to show the phenomenon at its best. The bulb is illuminated by the ultra-violet ray of wave length 2536 A.U. from a quartz mercury arc. This ray is separated from the others by a prism and focussed at the centre of the bulb by a quartz lens. A photograph made with a camera provided with a quartz lens shows the cone of resonance radiation stretching right across the bulb. If the bulb is heated slightly, the resonance radia tion retreats to the wall at the point where the radiation enters it, as the rays are no longer able to penetrate more than a very minute depth of the vapour. If the bulb is cooled it is found that the resonance radiation of the vapour can be detected at a tem perature of — so° C, that is, r o° below the freezing point of mercury. This showed that even the solid metal gave off sufficient vapour to absorb and re-emit the light. Bulbs rendered luminous in this way have been named "resonance lamps," and have proved of use in various investigations as they give off radiations even more homogeneous, or monochromatic, than the lamps which excite them.

The next step in the development which we must consider is the observation made in 1915 by R. J. Strutt (now Lord Rayleigh) that sodium vapour, illuminated by the ultra-violet light of a zinc spark (which emits a radiation of the same wave-length as one of the sodium ultra-violet lines), emits a yellow light of the same wave-length as when excited to resonance radiation by the yellow light of a sodium flame. This is the simplest and most elementary case of fluorescence which we have, and its explanation is clear from the viewpoint of Bohr's theory. By the absorption of the ultra-violet light the electron is raised to a higher orbit than that in which it originally revolved. The return to the normal state may now take place in either of two ways. It may return directly, in which case ultra-violet resonance radiation occurs, or it may be shaken out of this orbit into a lower one by collisions with other atoms, and from here return to the inner orbit with the emission of the yellow light. In this case Stokes's law is obeyed, for it has not yet been found possible to get the ultra-violet line by excitation with yellow light.

Slightly more complicated is the case observed by Fuchtbauer, who found that mercury vapour in vacuo in a tube of fused quartz glowed with a green light when illuminated by the total radiation of a quartz mercury arc, and the spectroscope showed that prac tically all of the spectrum lines of the mercury arc were being emitted by the vapour. These other rays are not emitted as res onance radiation, however, for if a glass plate, which cuts off the ultra-violet but not the visible rays, is interposed between the arc and the tube containing the vapour, the luminosity vanishes, although the vapour is still powerfully illuminated. For these other rays to be produced it is necessary that the vapour be illu minated by the ultra-violet ray X2536, and the glass plate absorbs this. The processes involved in this case are completely in accord with Bohr's theory of absorption and re-emission. Mercury vapour in the normal state absorbs only ultra-violet light, by which it is brought into the excited condition (electrons in higher orbits), and while in this condition it can absorb some, but not all, of the visible radiations. By the absorption of the violet ray A4046, the electron is carried to an orbit still further removed, and it may return to any one of three inner orbits, the green line being emitted in one case. We are here dealing also with a very simple case of fluorescence, namely the emission of green light resulting from the absorption of blue. Fuchtbauer's observations have been extended by R. W. Wood, who illuminated the vapour by various combinations of rays from the lamp and studied the orbital transitions of the electrons which resulted. One of the most striking and interesting results of the study was the dis covery that emitted light, which resulted from two successive absorption processes, increased as the square of the intensity of the exciting light, while certain other spectrum lines, the emission of which required three successive absorptions, increased as the cube, a circumstance perfectly in accord with theory.

Resonance radiation and the simple types of fluorescence ex hibited by sodium and mercury vapour, which have just been described, are phenomena of the atom, the vapours of sodium and mercury at low pressure being monatomic. When these vapours are formed at higher pressure by raising the temperature of the bulbs, some of the atoms combine to form diatomic mole cules, and a new type of absorption and fluorescence manifests itself. If white light is passed through the dense sodium vapour and examined with a spectroscope, a very complicated absorption spectrum consisting of fluted bands is seen, and a similar spec trum can be seen with the vapour of iodine at room temperature. These bands we now believe to be the result of three different disturbances produced in the molecule, an orbital displacement of the electrons in the atoms, a vibration of the two atoms along the line joining them, and a rotation of the molecule as a whole. (See BAND SPECTRUM.) If sun or arc light is concentrated upon the vapour, it glows with a greenish light, the spectrum of which consists of bands similar in their general appearance to the ab sorption bands. A photograph of the fluorescence of iodine vapour at room temperature in a large glass bulb is shown (Plate I., fig. 3). The path of the illuminating beam from the arc to the bulb was made visible by blowing a little smoke into the region between them. The bulb is highly exhausted, and contains a small crystal of iodine. If air is admitted to the bulb, even in a minute quan tity, the fluorescence disappears. This is true fluorescence, for if we illuminate with monochromatic light, we find many other wave-lengths or colours in the emitted light, the vapours giving out light which the spectroscope shows as double lines spaced at sensibly equal intervals along the spectrum (R. W. Wood; Phil. Mag., 1912). These spectra have been fully accounted for theo retically by Lenz, and have proved useful in the analysis of the very complicated band spectra, which are made up of fine lines to the number of some 50,000 or 6o,000 in the case of iodine. Stokes's law is violated conspicuously in the case of these resonance spectra, for lines frequently appear on the short wave length side of the line which excites the vapour. If helium or some other chemically inert gas is mixed with the iodine vapour, and illuminated say with the green line of the mercury arc, the widely spaced double lines fade away and the band spectrum appears in its place. This forms the stepping-stone between the vapour fluorescence, and the fluorescence of a liquid or solution, for by the introduction of the helium we note the effects of the collisions of the molecules on the emission spectrum, and in a solution we have this same effect to an enhanced degree. It appears that the effect of the collisions, in the case of iodine, is to change the rotational energy of the molecules by different amounts, with the result that, during their return to the normal state, each one emits a radiation of a definite frequency depending upon the change in its rotational energy produced by the collision. In general, the effect of an impact with another molecule is to de crease the internal energy of an excited molecule, which will result in the emission of a radiation of lower frequency than that of the exciting light, the excess energy being spent in increasing the velocity of the rebounding molecules, i.e., in raising the tem perature of the vapour. It may happen in some cases that some of the kinetic energy of the colliding molecules is spent in raising the energy of vibration or rotation, and this gained energy is given off again when the molecule returns to its normal state. It is in this way that we may have the higher frequencies radiated con trary to Stokes's law, without violating the energy relations of the quantum theory.

The case of benzene is of especial interest as it exhibits fluores cence in the vapour, fluid and solid state, and also when in solu tion in another liquid. The behaviour of the vapour under optical excitation resembles that of iodine in some respects, and a study of the substance in its several states has shown that it may pos sibly be regarded as a connecting link between the phenomena exhibited by sodium and iodine vapours, which are comparatively well understood, and those presented by aniline dyes and other complicated organic compounds, in regard to which we have no very complete or satisfactory theory.

Efficiency Factor.

By this we mean the ratio of the absorbed energy to that which is re-emitted as fluorescence. If we illuminate a solution of fluorescein with monochromatic light obtained from a spectroscope, we find that the intensity of the fluorescence varies greatly as we alter the colour of the exciting light. As we have seen, the complete fluorescence spectrum is radiated regardless of the wave-length of the exciting light, if it is capable of exciting any fluorescence at all, and it is this circumstance that causes Stokes's law to break down in cases when the absorption band and fluorescence band overlap. It was shown by Nichols and Merritt that all wave-lengths are equally efficient in exciting fluorescence if we compare the fluorescence with the amount of light actually absorbed. Now in the case of resonance radiation of a metal vapour in a high vacuum it has been found that all of the energy extracted from the exciting beam of light is re-emitted, there being no true absorption, but if some other gas is present, true absorp tion at once appears and the intensity of the resonance radiation is diminished. In the case of fluorescence the efficiency was deter mined for a number of substances by Wawilow (Zeit. fur Physik, 1924), who measured the amount of the absorbed light with a photometer and compared it with the fluorescent light scattered by the solution, and by a diffusing screen of magnesium oxide. The highest efficiency was found for fluorescein which showed an efficiency of 75%, while some dyes showed values as low as 2% or less. An efficiency of 75% means that three-quarters of the energy of the absorbed light is re-emitted as fluorescent light. It is this high efficiency which makes possible the Cooper-Hewitt "light transformer" which is described under Applications of Fluorescence.The intensity of the fluorescent light in the case of most solu tions varies enormously with the concentration, and falls to zero if the concentration becomes too great. This can be well shown with fluorescein, which exhibits its most brilliant effect only in extremely dilute solutions, and becomes non-luminous if the concentration is increased beyond a certain point. We are quite in the dark in regard to the cause of this effect. All that can be said is that the close proximity of the fluorescent molecules prevents the re-emission of radiation, the mystery being why a fluorescein molecule interferes with the functioning of its neighbours any more than the water molecules. A similar behaviour in the case of benzene has already been mentioned.

Fluorescence of Uranium Compounds.

Though there are countless organic compounds which show fluorescence, very few inorganic substances exhibit the phenomenon, though many of them have absorption bands of the same general character as those of the fluorescent organic compounds. Until we can explain why a solution of potassium permanganate, with its beautiful absorption bands in the green region of the spectrum, shows no trace of fluorescence, while a solution of rhodamin which has similar absorption bands and colour, glows vividly under illumina tion, we cannot claim to have a very definite view of the under lying causes. It seems probable that in fluorescent bodies, such as benzene and other aromatic compounds, and certain salts of uranium, the electron system of the atom which causes absorp tion and fluorescence is shielded in some way from the disturbing influence of neighbouring atoms. The salts of uranium and the platino-cyanides are among the few inorganic compounds which show conspicuous fluorescence, and it is only the uranyl salts that show the phenomenon, the uranous compounds exhibiting no trace of luminosity.Various compounds of uranium were studied by Stokes, who found that some of them exhibited fluorescence in solution as well as in the crystalline state. He found that the spectrum consisted of well-defined bands arranged at regular intervals, and that the absorption spectrum in the blue and violet region exhibited a series of bands of similar appearance. An exhaustive study of the sub ject was undertaken in 1872 by E. Becquerel, who discovered that the fluorescent crystals of the uranyl salts were also phosphores cent, that is they continued to glow for several thousandths of a second of ter the illuminating rays had been cut off. He found also that the fluorescent and phosphorescent spectra were identical in structure, from which he concluded that the two phenomena were not really distinct. According to our present views, however, we should not call this phosphorescence, but fluorescence of long duration. In more recent times a very comprehensive study of these salts has been made by Nichols and Merritt. In 1903 the very important observation was made by J. Becquerel and Kam merlingh Onnes, working with uranyl salts in the cryogenic labo ratory of the latter at Leyden, that at the temperature of liquid air (-185° C) each band of the fluorescent spectrum broke up into a number of narrower bands. At the temperature of liquid hydrogen the components of the band became almost as narrow as the lines of a spark spectrum.

The chief point of interest in connection with the fluorescence of the uranyl salts is the similarity of their behaviour to that of benzene. The broad bands at room temperature, the breaking up of these bands into narrower bands at low temperature, the over lapping of the region of absorption and fluorescence are common to both substances. While the fluorescence of the crystals of the uranium salts is very bright, that of their solutions in water is in general very feeble. Francis Perrin has found that solutions in sulphuric acid fluoresce much more powerfully, and that the flu orescence is of long enough duration to be seen with the phos phoroscope, an instrument which will be described presently. This is the first case recorded of a "phosphorescent" liquid. It is prob able that the molecules in this case are in an environment similar to that obtaining in the case of uranium (or "canary") glass, which also exhibits a fluorescence of long duration in the phosphoroscope.

The platino-cyanides of barium, magnesium, potassium and other metals form another group of fluorescent crystals. These compounds differ from the uranium salts in that they show no trace of luminosity in solution, and their solutions are as clear and free from colour as pure water, though the salts are highly coloured. In some respects they resemble the true phosphores cent compounds, which we shall now consider.

Phosphorescence.

This term, as formerly applied, would cover all cases in which the emission of light persisted, even if only for a minute fraction of a second, of ter the exciting light had been cut off. As has been said, if we adopt this definition, no sharp line can be drawn between fluorescence and phosphorescence. The term, as now used, applies to a class of bodies in which very minute traces of metallic impurities in crystalline substances give them the power of emitting light for a longer or shorter time after exposure to a strong illumination. Such substances are termed "phosphors." Many of the substances studied by A. C. Becquerel, in his pioneer investigations, we should now class as fluorescent. He devised an instrument which he named the phosphoroscope, in 'which the substance was contained in a dark box between two wheels perforated by slots which were arranged out-of-step; these wheels were mounted on a common axle, and could be rotated at high speed by a system of gears. The illuminating beam reached the substance through the slots of one of the wheels, while the observations were made through the perforations of the other. This enabled the viewing of the substance in the dark in the very brief intervals between the flashes of light which illuminated it. With this instrument Becquerel discovered the phosphorescence of an enormous number of substances, and measured the duration of the phenomenon, as affected by the temperature, colour of the exciting light and other factors.Crystals of uranium nitrate, fluor spar, gems and many other minerals glow with brilliant colours in this instrument. The foun dations of our knowledge regarding the nature of the true phos phorescent bodies, as distinguished from fluorescent bodies show ing a slight persistence of luminosity, was laid by the researches of P. Lenard and his collaborators. They found that the phosphor escent properties of the metallic sulphides were due to very minute traces of other metals by which they were rendered active. The maximum intensity of the phosphorescence is obtained with a certain definite proportion of the impurity, an excess decreasing it. In some cases phosphorescence is produced by as little as 10 000% of the impurity.

The earlier work on phosphorescence was hampered by the imperfect methods of purification of the chemicals employed in the preparation of "phosphors." It was found difficult to dupli cate results, and the production of a satisfactory phosphor by fol lowing a recommended specification was often a matter of luck. The researches of Becquerel, ti erneuil, Boisbaudrans and Wiede mann gave evidence of the part played by impurities, but Lenard was the first to examine the conditions systematically, preparing his phosphors from carefully weighed amounts of the purest materials obtainable. He employed metallic sulphides, oxides and selenides as the foundation material, adding minute traces of other metals as the activating substance, the mixture being heated, usually with a flux of sodium chloride or sulphate, to a high temperature in a furnace. Phosphors can also be pre pared by crystallization from solutions, and this method was the one usually employed by Wiedemann. These, however, do not exhibit as brilliant a phosphorescence as those obtained by the furnace method. Cadmium sulphate, recently studied by Wag goner, is a good example of phosphors of this class. The purest salt obtainable commercially, phosphoresces when illuminated by ultra-violet light, but if further purified by repeated fractional crystallization, shows no trace of luminosity. The addition of o• 1 % of zinc sulphate causes the appearance of an intense blue phosphorescence; magnesium or sodium salts added as impurities cause yellow or green phosphorescence.

The present view is that all of these phosphorescent bodies are crystalline, the molecules of the impurity deforming the crystal lattice. This, while contrary to the former views of Lenard, who considered his phosphors amorphous, has been confirmed by X-ray photographs made by the method of Debye and Scherrer. An in teresting case is that of calcium tungstate, the material used in the preparation of X-ray fluorescent screens. Obtained as an amorphous or non-crystalline precipitate from solution, and even if activated by impurities, it shows no trace of phosphorescence. On allowing it to stand for some time it changes gradually into the crystalline modification, as shown by X-ray photographs, in which state it exhibits phosphorescence. The change can be accomplished more rapidly by heating the amorphous powder, but the temperature must not exceed 1,000° C.

Quenching of Phosphorescence by Red and Infrared Rays.—Seebeck discovered that orange or red light falling upon a phosphorescent substance, excited to luminosity by violet or blue light, destroyed the phosphorescence completely. This dis covery, though recorded in Goethe's Farbenlehre, remained com paratively unknown, and the phenomenon was rediscovered many years later by E. Becquerel, who investigated it more fully and found that the quenching of the phosphorescence by orange or red light was preceded by a momentary increase in the intensity of the luminosity followed by complete darkness. It appeared as if the red rays squeezed out all of the stored light in a few moments, and he attributed the effect to the heating action of the rays, for he had found that the same thing could be accomplished by warming the substance. He found further that the infra-red rays acted in the same manner and his son, H. Becquerel, con tinued the investigation, and in 1883 studied the invisible region of the solar spectrum, beyond the red as far as 1.5,u (wave-length double that of the extreme visible red), by projecting the spec trum on a luminous screen excited to phosphorescence, and observ ing the darkening produced by the invisible rays. J. W. Draper improved the process by laying the partially darkened phosphores cent screen upon a photographic plate thus obtaining a permanent record. This method of phosphoro-photography of the infra-red was subsequently employed by Lommel, Dahms and others, but nothing of much importance has been accomplished by it.

Dahms in 1904 made the interesting observation that the lumi nosity of the zinc sulphide phosphors is quenched by red and infra-red radiations without any momentary increase, which shows that there are two distinct types of quenching. Balmain's luminous paint is an example of the first type. Under infra-red illumina tion, the phosphorescing material suddenly gives out a greenish light, quite different in colour from the violet glow which it emitted before the infra-red rays played upon it. If warmed slightly with a heated glass rod there is also an increase in luminosity, but in this case the colour is unaltered. This proves that the action of the infra-red rays is not merely a heating effect. The zinc-sulphide phosphors, which are now extensively used for stage effects, are examples of the second type of quenching. They rapidly darken under the action of infra-red rays without any preliminary increase of luminosity.

Lenard discovered that the absorption spectrum of an excited (i.e., luminous) phosphor was different from that of the unexcited. The absorption bands in the ultra-violet disappeared under power ful illumination, and were replaced by new bands in the longer wave-length region. It is from absorption by these new bands that the quenching results. This change in the molecular state also manifests itself in other ways. The magnetic and dielectric prop erties of the phosphors are found to be different before and after illumination. Elster and Geitel found that both natural and artificial phosphors exhibited the photo-electric effect, i.e., they gave off electrons when illuminated, and Lenard, following the matter up, found that the photo-electric emission and the phos phorescence were caused by absorption of radiation of the same wave-lengths. His theory of phosphorescence supposed that the absorption of light resulted in the ejection of an electron from an atom, and its capture by a neighbouring atom, the phosphores cence resulting from the gradual return of the captured electrons to their former places, the energy set free in this process being communicated to another electron and eventually radiated as light of longer wave-length.

The modern theory of the phenomenon rests chiefly on the recent work of Gudden and Pohl, who found that many non phosphorescent (i.e., "pure") crystals conducted electricity when illuminated by light. This may be called an "internal photo-elec tric effect," the electrons set free by the light, travelling through the crystal lattice to the anode, under the influence of the applied electromotive force. It is only in a crystal, the space lattice of which is distorted by foreign atoms (impurities), that the return of the electrons ejected by the light causes an emission of radia tion. Experiments on the electrical conductivity of these crystals have shown that the electrons do not traverse the distorted lat tice freely, as in "pure" crystals, but that many are captured on their way to the anode by atoms. It has recently been found by Rupp that the electric current, which flows in a phosphorescent crystal (under an applied electric force) during its illumination, and ceases as soon as the illuminating rays are cut off, starts up again if the crystal is warmed or illuminated by infra-red rays, and that the amount of electricity transported is proportional to the amount of light emitted.

If a "pure" crystal is illuminated in the absence of an electric field the electrons ejected from atoms by the light move about freely in the lattice, and the local fields, which result from the ejections, recapture them as soon as the illumination ceases, and no current will flow under an applied electric force when the crystal is warmed. In the distorted lattice of a phosphorescent crystal, on the contrary, the ejected electrons are captured by other atoms, and if such a crystal is illuminated for a definite time, and the photo-electric current, which flows during the illumination is measured, an equal amount of electricity will flow, on cutting off the illumination and warming the crystal.

Applications of Fluorescence and Phosphorescence.— Fluorescence can be utilized for illustrating or studying the pass age of rays of light through liquids. The curved rays of light forming focal points in a non-homogeneous medium (see R. W. Wood, Physical Optics) were made in this way, a small amount of sulphate of quinine having been added to the solution. The ultra-violet portion of the spectrum can be rendered visible, and a small pocket spectroscope has recently appeared provided with a fluorescent screen for examining the spectra of sources of light rich in ultra-violet rays. The fluorescence of mineral oils is made use of in a process for the photography of the extreme ultra-violet in investigations with the vacuum spectrograph. Ordinary plates are insensitive to these rays as the gelatine film, in which the sensitive silver salts are embedded, is opaque to the light, but if a thin film of oil is smeared over the film, it becomes fluorescent when the spectrum lines are focussed on it, and this fluorescent light records itself on the plate.

Fluorescence has even been utilized for purposes of general illumination. The mercury arc, one of the cheapest artificial sources of light, suffers from the disadvantage that it gives out little or no red light, with the result that under its illumination, few objects appear in their proper colours, and the human face takes on a ghastly greenish hue, spotted with blue. The idea occurred to Cooper-Hewitt, the inventor of the commercial form of the lamp, to make use of the fluorescence of rhodamine to supply the missing red rays. He devised a white reflector coated with a film of celluloid stained with the dye, which, when mounted above the arc, glowed with a bright vermilion colour, adding its rays to those of the lamp, and producing an illumination not very different from daylight. This reflector he called a "light trans former." The efficiency of such a screen is much greater if the fluorescent film is formed on white paper or card than if it is de posited on a silver or tin reflector, in which case the fluorescence is surprisingly feeble. The cause of this was investigated (R. W. Wood, Phil. Mag., 1913) and found to result from the circum stance that the fluorescent light was imprisoned by total reflection in the case of the metal backing, whereas it was at once released by the diffusing surface of the paper.

Both fluorescence and phosphorescence have been utilized in recent years for the production of spectacular effects on a dark ened stage illuminated by the powerful ultra-violet lamps, de veloped during the war by R. W. Wood and described in the Journal de Physique (1919) . The lamp consists of a mercury arc (in a quartz tube), the light from which is filtered through glass coloured black with a carefully chosen amount of oxide of nickel. The ultra-violet radiations given out by such a lamp are so intense that the entire company in a large auditorium can be rendered fluorescent, fabrics shining with unusual colours, teeth and eyes glowing with a brilliant bluish light (false-teeth appear coal black) and practically everything in the room giving off light of a greater or less intensity. The lens of the eye is also fluorescent under the illumination, and this light falls upon the entire surface of the retina, producing a curious illusion ; the room appears to be filled with a bluish haze or smoke, which vanishes the instant the hand is held between the eye and the lamp. These lamps have had a wide application in other fields, such as the diagnosis of certain diseases in ,which the fluorescence of the tissues are examined in the dark by the ultra-violet radiations, the detection of adulterants in drugs and chemicals, the differentiation of cotton from silk in fabrics, the comparison of old paintings with recent copies, and so on.

Photographs showing some of these curious effects are repro duced (Plate II., figs. 6, 7 and 8) . Fig. 6 is a photograph of a white china plate in front of a journal. A slip of white writing paper, on which invisible writing has been printed with a solution of anthracene, is pasted across the plate. The fluorescence of these objects under ultra-violet illumination is shown by fig. 7. The white plate appears coal black, while the white paper is quite luminous, though not nearly as bright as the letters in anthracene. Fig. 8 is a photograph of a young woman, and shows the fluores cence of the lens (pupil) of the eye. The skin appears as dark as that of a mulatto, while the teeth are very brilliant.

The excitation of fluorescence or phosphorescence by the X-rays is utilized in the screens or fluoroscopes used for visual observa tions of the internal organs or bones. One very early application of phosphorescence was in the preparation of a paint which glowed in the dark; this so-called Balmain's luminous paint had a con siderable vogue during the latter half of the i 9th century. It was a calcium sulphide containing certain impurities on which its phosphorescence depended, and after exposure to a strong light remained luminous in the dark for some time. It was used for painting key-holes, gas and electric fixtures, and other objects which had to be located in the dark. It has been supplanted by the modern phosphorescent paints used on watch and clock dials, the luminosity of which is continually excited by a small content of radium. "Canary" glass, coloured by oxide of uranium, is used in the arts and owes its peculiar green luminosity to fluorescence, its colour by transmitted light being a pale yellow. The powerful fluorescence of extremely dilute solutions of an alkaline salt of fluorescein (uranine) has resulted in its employment for tracing possible seepage from drainage systems to springs or wells, a small quantity of the substance thrown into the drain causing the water in the well to show a green fluorescence if seepage occurs.